Ethics and Twitter

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

Can I avoid seeing hate speech and unsettling imagery and still analyze twitter?

What are some privacy or other ethical issues that you need to keep in mind when harvesting tweets with twarc?

How much personal information can we actually gather about a user given our twarc scrape?

What are some use cases that might be inappropriate?

Objectives

Let’s Get Ethical

There are multiple ethical issues to consider when using Twitter data. In this lesson, we will be focusing on #FIXME issues: authorship, privacy, and consent. Ultimately, all three concern personhood.

Authorship, the GDPR, and the Right to be Forgotten

Twitter users maintain ownership of their tweets. As the author, users have both copyrights and moral rights. (Only the former is defined in the United States.)

Copyrights prevent your tweets from being compiled together into a publication for profit. That said, some authors do not have any copyrights. For example, POTUS is an American government employee, therefore that ‘property’ is in the Public Domain.

Laws vary greatly by country, so don’t get American librarians started on the Queen’s copyrights over Canadian government data, which is complicated.

Moral rights are more complicated. Laws vary greatly by country–even moreso than copyright. In the European Union, authorship includes the right to un-publish, in other words, the right to be forgotten. Twitter, very cleverly, preserves this right by letting us delete our tweets.

Personally Identifiable Data

It’s very easy to match up data to a human being. Conversely, it is very difficult to remove something from the Internet once it is there. The European Union has created the General Data Protection Regulation to protect people’s identities as well as to respect the privacy rights of “natural persons” (as distinct from public figures and corporations).

The GDPR defines Personal Data as:

What is Personal Data?

Personal data are any information which are related to an identified or identifiable natural person.

The data subjects are identifiable if they can be directly or indirectly identified, especially by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or one of several special characteristics, which expresses the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, commercial, cultural or social identity of these natural persons…

Citation: “EUR-Lex – 32016R0679 – EN – EUR-Lex”. eur-lex.europa.eu.

Discussion: Personal Data

- Do you think that Twitter data should be treated as personal data?

- What did you consider when making this judgment?

- Are robots people?

- Do the blue checkmark people deserve privacy?

Considerations

We get a lot of personal information when we gather tweets. We can often determine a user’s approximate location, what they like, their beliefs, etc.

Even though some people treat Twitter like a diary, even though it is a public space, researchers still need to respect their personhood.

As scholars, we also have an obligation to treat this information carefuly. Both at the granular, individual level, and at the dataset level.

The first few minutes of this standup comedy routine shows the hazards of sharing too much personal information on social media

Protecting yourself

Distance Reading

Researching tweets on Twitter may expose you to hate speech, and possibly disturbing imagery. Fortunately, when we work with thousands of tweets at a time, we do so at a distance, so we can avoid consuming disturbing content directly.

The first step in distance reading is to get at the language–the actual tweets.

Wordcounts with Textblob

Looking at the most commonly used words and phrases in a dataset is a text analysis practice. This helps us to get a sense of what we are dealing with in our dataset.

In Text Data Mining, a complete list of words and their frequency of appearance can be called a “concordance.” We would consider texts of the tweets themseves to be the corpus. Everything else is metadata.

We will use the TextBlob package for our full-text analyses, including getting a word count. The most used words in your dataset can be used to judge the tone of the overall content without needing to wade through thousands of tweets.

Let’s remind ourselves what dataframes we have available to work with:

# %who DataFrame

ecodatasci_df hashtag_gasprices_df hashtagcats_df

kittens_df library_timeline_df riots_dehydrated_df

ucsb_library_mentions_df

And let’s remind ourselves which column we need

library_timeline_df.columns

hashtagcats_df['text'].head()

So that’s the column to pull data into a python list:

list_tweets = hashtagcats_df['text'].tolist()

Next, we use the python join function to insert spaces between words and

make this list into one long string of text.

string_tweets = ' '.join(list_tweets)

All this was to get our tweets into a string because TextBlob has its own data

format, so we needed a string to pass to textblob. The function TextBlob converts the

string of tweets to a textblob.

library_blob = TextBlob(string_tweets)

Now that we have our TextBlob, we can count and sort it. We do this using the

python function word_counts and sorted.

library_freq = library_blob.word_counts

library_sorted_freq = sorted(library_freq.items(),

key = lambda kv: kv[1], reverse = True)

print(library_sorted_freq)

This shows a lot of text with no meaning though. To help with this, we can get rid of

English stop words, like all the a’s, and’s, and the’s. nltk, which got installed

along with textblob, has its own corpus of stopwords we can use:

# load the stopwords to use:

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

# sw_nltk is our dictionary of stopwords

sw_nltk = stopwords.words('english')

# create a new object without the stopwords

library_blob_stopped = textblob.TextBlob(library_words_stopped)

library_blob_stopped_freq = library_blob_stopped.word_counts

library_blob_stopped_sorted_freq = sorted(library_blob_stopped_freq.items(),

key = lambda kv: kv[1],

reverse = True)

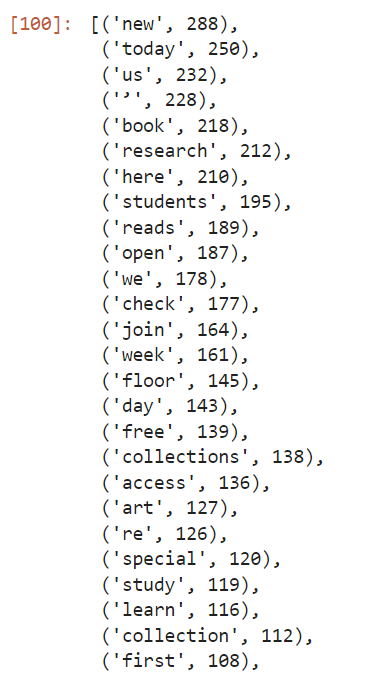

library_blob_stopped_sorted_freq[1:50]

Lastly, we want to cut off the most used, which are http, ucsb, etc.

library_blob_stopped_sorted_freq[7:57]

[('new', 288),

('today', 250),

('us', 232),

('’', 228),

('book', 218),

('research', 212),

('here', 210),

('students', 195),

('reads', 189),

('open', 187),

('we', 178),

('check', 177),

('join', 164),

('week', 161),

('floor', 145),

('day', 143),

('free', 139),

('collections', 138),

('access', 136),

('art', 127),

...

Our results make sense. We can see that the words are associated with library-like things. This text is worth some further examination.

If we were expecting hate speech, this is where we would start to see it. If some of the top words are inflammatory, we can bet that the content of the whole datset will make some squeamish.

A more sophisticated text analysis would include passing this through another filter to remove the one and two letter words and the URL’s.

There are also functions to pull phrases out of text corpuses, which is one form of what is called tokenization.

Disinformation

Twitter already removes a lot of violent and obscene content, but it does pride itself on being a free speech platform. Mainly, Twitter removes content that violates its Terms of Use. In some countries some content might be downright illegal and Twitter would be obliged to delete it or otherwise restrict access to it. Sometimes this means removing entire accounts, such as that of the former US President and many of his associates.

Misinformation

Nature disinformation cloud

Speaking of which, let’s see how much data from January 6th, 2021 is still available.

Challenge: January 6 Insurrectionists

After the US Capitol riot, a user on kaggle captured 80,000 Tweets from people associated with that day’s events, concentrating on accounts from those protesting / rioting.

This kaggle user, in the public interest, stored the full content of these Tweets as a .csv. The best practice would be to save only a dehydrated set of tweets. However, in this instance, we can use this person’s conscientious objection to social norms and Twitter’s Terms-of-Service to ask whether or not any of this is in the public good or an acceptable topic of research.

Using the file dehydrated_Capitol_Rioters.txt, determine how many Tweets were in the archive, and how many remain on Mr. Musk’s new acquisition.

Solution

When we first ran this, only a tiny fraction of the tweets remained. But more recently, we noticed that about 80% gets rehydrated. We suspect that Twitter has restored some of this content.

New Challenge???

That riot file is too big to work with on the fly. We need something a bit different. First thought is to give a list of accounts and see who is still online?

Second thought: there’s 58135 users in the rehydrated file. But they are mostly retweets. By getting out the users quoted, we can see that there’s many fewer original authors. How few? #FIXME

Chop the dataset to be the first 10,000 lines:

! head -n 10000 output/riots_flat.jsonl > output/riots10k.jsonl

! twarc2 csv output/riots10k.jsonl > output/riots10k.csv

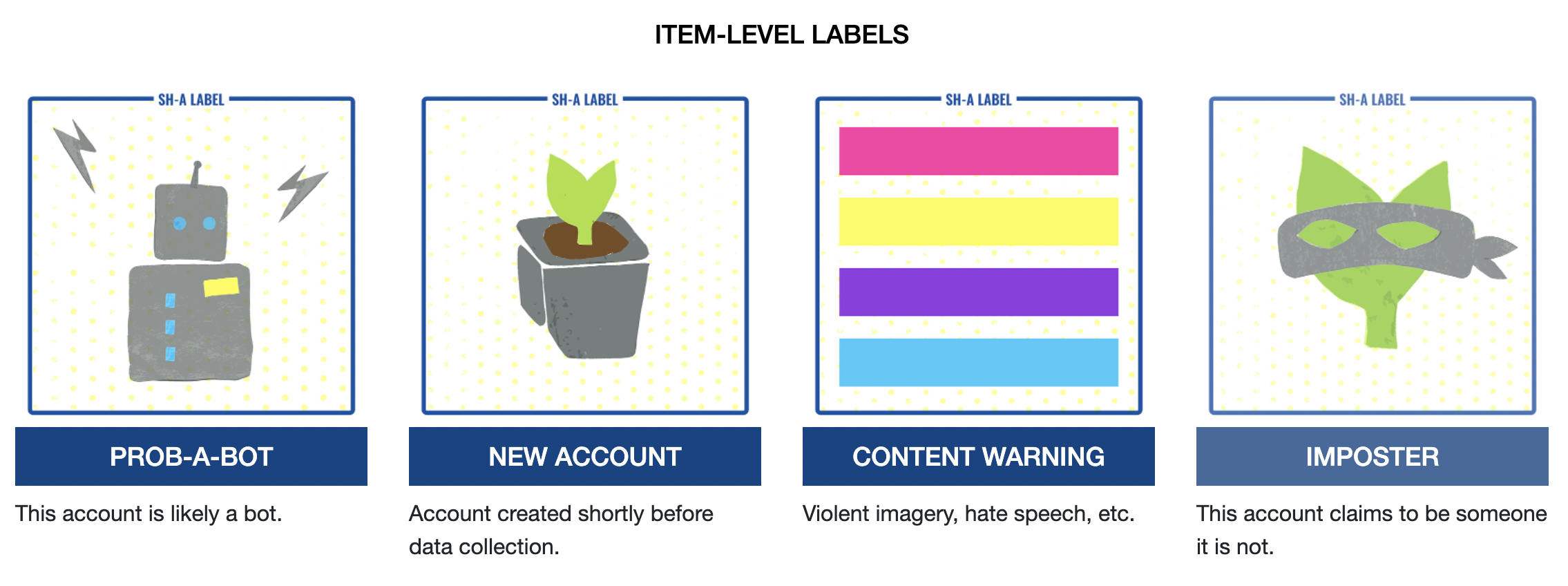

Sort our 10,000 by account created date. New accounts can have a SH-A tag applied to them.

Social Humans and robots

Documenting the Now has released a classification scheme to apply to Twitter accounts. We can apply these ‘Social Humans’ labels to individual Tweets and/or accounts to identify bots, trolls, and malicious actors.

Adding a column to our dataframe and classifying tweets according to what sort of entity we think posted them is a very useful flavor of analysis

code to add a column to the list of authors we pulled above?

Key Points