R introduction: Beyond Base R

Overview

Teaching: 35 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How do we go beyond R’s base functionality?

Objectives

Be able to load extra libraries to extend R’s possibilities

Be able to create plots using ggplot2

Understand how to perform a 4PL curve fit on example data

See how to code a basic loop function in R

Loading packages

We’ve seen how R comes with a variety of built-in functions, and we’ve used many of them to perform various tasks. R can also be extended using any of thousands of additional libraries, each of which comes with several new functions. For a list of all of these libraries (also known as packages), see the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) website here.

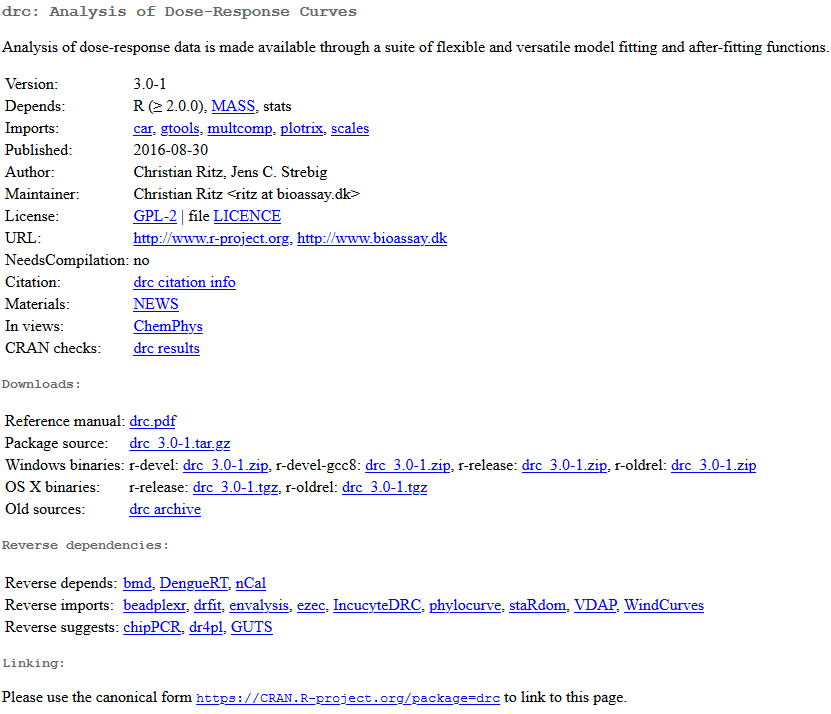

This list can be overwhelming. Go to ‘find’ on your browser and type in ‘drc’. Go through the matched items until you see the package called ‘drc’. Click on it and you’ll see that it’s described as “Analysis of dose-response data is made available through a suite of flexible and versatile model fitting and after-fitting functions.”

There is a lot of information here. The part that’s possibly of the most use is the reference manual in the form of a PDF. Every package in R comes with a reference manual like this, and outlines all of the additional functions and how to use them. We’ll return to this package later.

ggplot2

The first package we’ll use is called ggplot2, where ‘gg’ stands for ‘grammar of graphics’. This is the main plotting tool used in R for producing professional plots.

First, you’ll need to install the package with the following code,

install.packages('ggplot2')

And then load it with,

library('ggplot2')

Let’s take a look at how to use this new package,

elisa = read.csv('../data/data_carpentry_test_data.csv') #Load the data

colnames(elisa) = paste0('Col_', seq(1:13)) #Change the column names

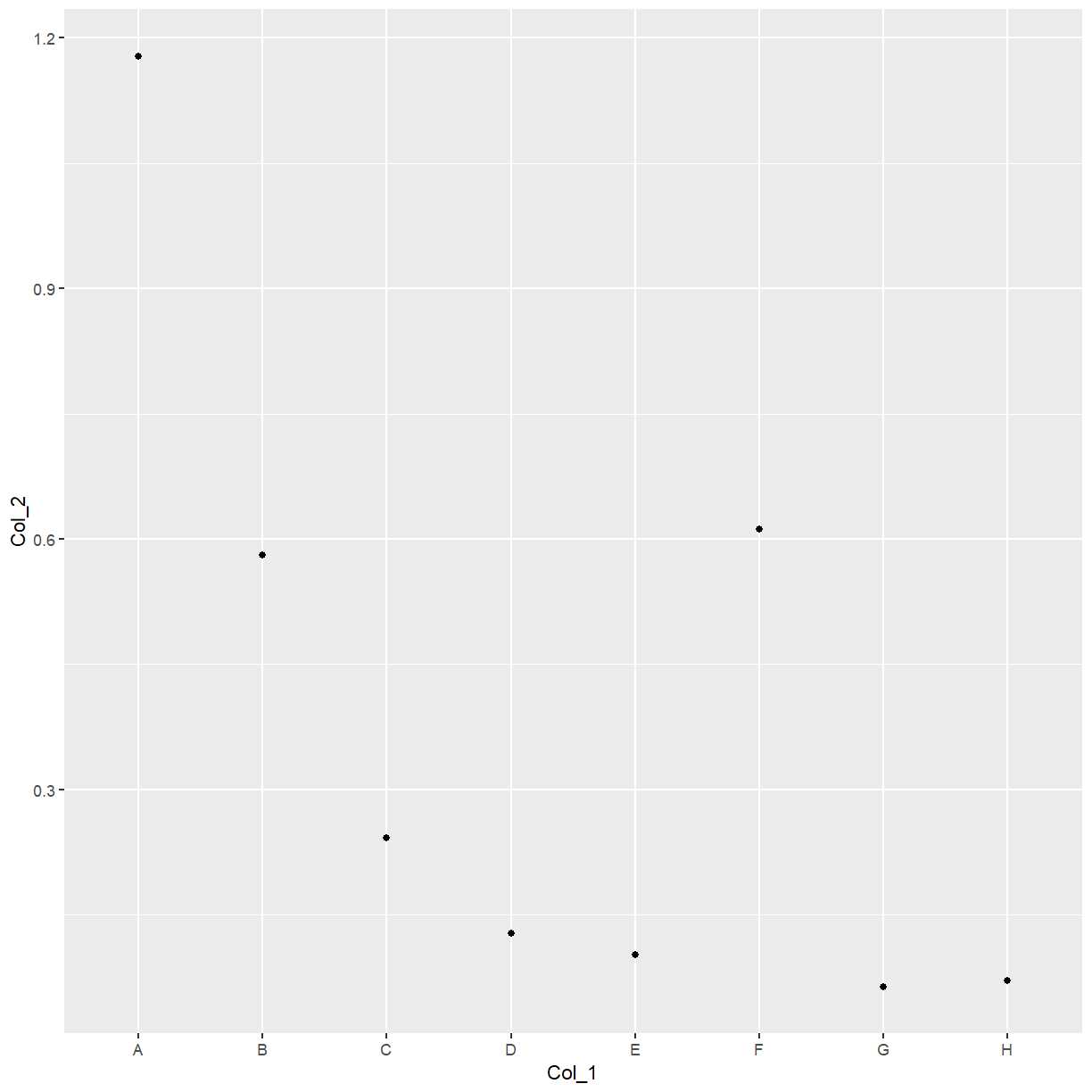

ggplot(data = elisa, aes(x=Col_1, y=Col_2)) +

geom_point()

With ggplot, you build up the plot line-by-line.

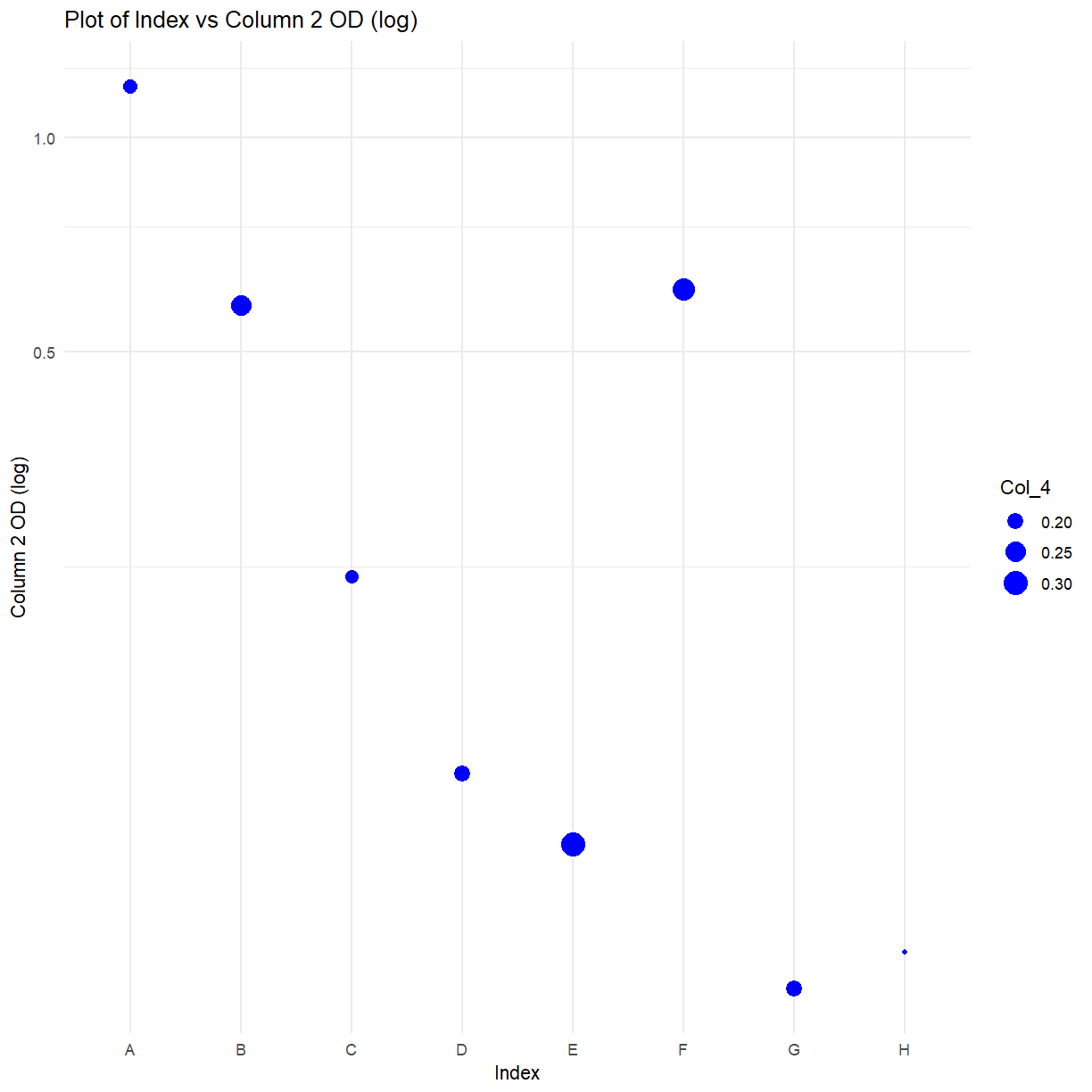

ggplot(data = elisa, aes(x=Col_1, y=Col_2, size = Col_4)) + #Create the basic plot, of column 1 vs column 2 vs column 3

geom_point(col = 'blue') + #Create the blue points

xlab("Index") + #Add an x-label

ylab("Column 2 OD (log)") + #Add a y-label

ggtitle("Plot of Index vs Column 2 OD (log)") + #Add a title

coord_trans(y="log") +

theme_minimal() #Set to the minimal theme

Exercise: CRAN

Take a look at the CRAN page and manual for ggplot2. Can you apply the function ‘coord_flip()’ to the above code? Have a look in the manual for guidance

Solution

Add '+ coord_flip()' as a new line to the code above

4PL fitting with drc

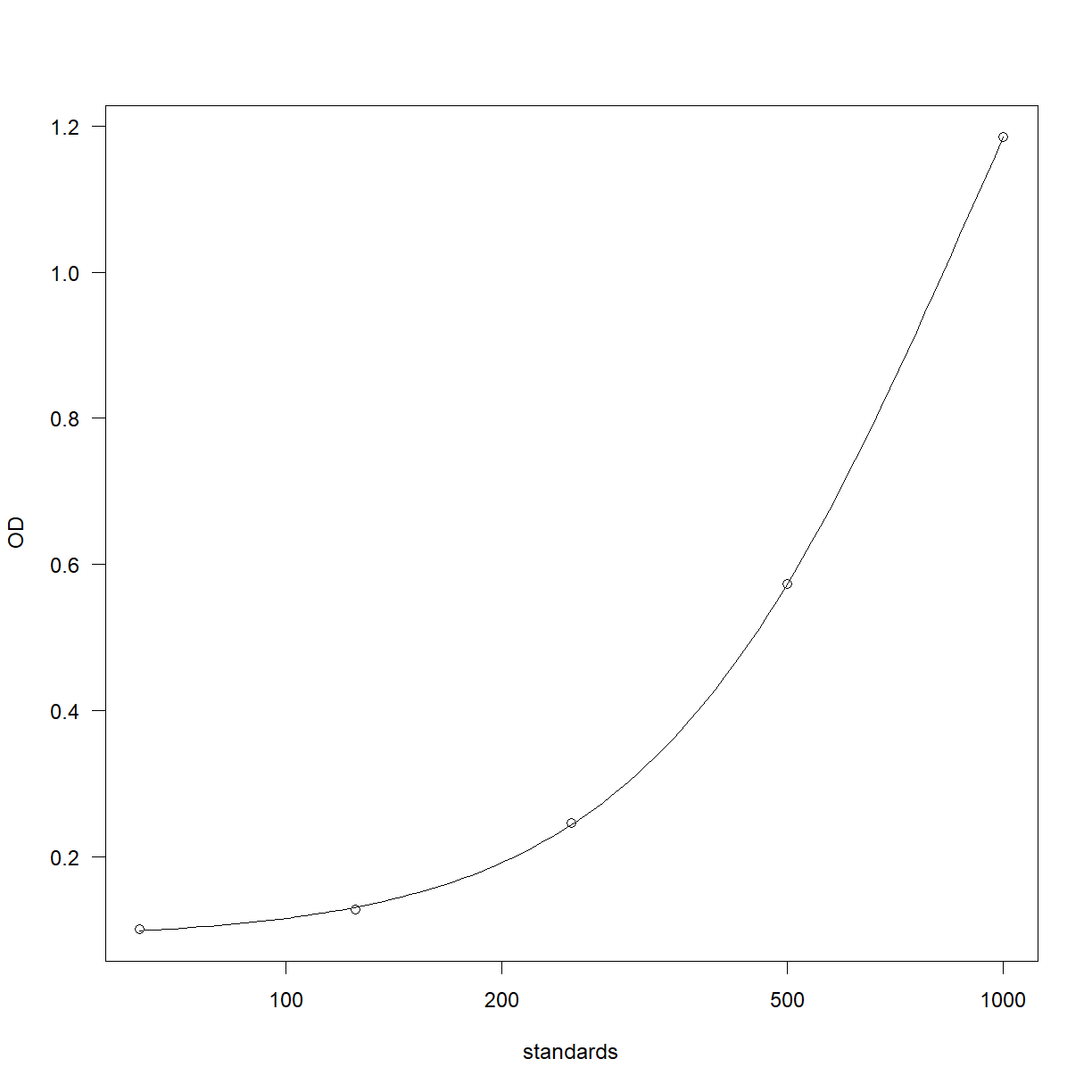

This section installs and loads the drc package designed for the fitting of standard curves.

Note that this section is aimed at demonstrating the use of external libraries. Don’t worry at this stage if you don’t understand everything that’s going on.

library(drc) #Load the package

elisa_stds = elisa[c(1:5),c(1:3)] #based upon the plate definitions

elisa_stds$standards = c(1000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5) #Add a column of standard values

elisa_stds$log_conc = log10(elisa_stds$standards) #Log the standard values

elisa_stds$OD=rowMeans(elisa_stds[,c(2, 3)], na.rm=TRUE) #Calculate row means for the OD column

Fit the curve and plot the results,

curve_4pl = drm(OD ~ standards,

fct=LL.4(),

data=elisa_stds)

plot(curve_4pl)

Work out the curve backfit and recovery,

elisa_stds$backfit <- ED(curve_4pl, elisa_stds$OD, type="absolute", display=F)

elisa_stds$recovery = (elisa_stds$backfit/elisa_stds$standards)*100

Work out the sample backfits,

Sample_backfits = ED(curve_4pl, c(elisa$Col_4, elisa$Col_5, elisa$Col_6, elisa$Col_7, elisa$Col_8[1:4]), type="absolute", display=T)

Estimated effective doses

Estimate Std. Error

e:1:0.189 196.4573 3.9012

e:1:0.255 259.6468 6.5999

e:1:0.18 186.7528 3.6861

e:1:0.202 209.8981 4.2991

e:1:0.307 303.4195 9.3673

e:1:0.275 276.9297 7.6276

e:1:0.207 214.9094 4.4755

e:1:0.151 152.4787 3.3986

e:1:0.105 77.8801 3.7311

e:1:0.112 92.5181 3.7271

e:1:0.085 NA NA

e:1:0.231 237.9525 5.4588

e:1:0.099 63.0539 3.6323

e:1:0.384 363.1657 13.8547

e:1:0.08 NA NA

e:1:0.229 236.0891 5.3698

e:1:0.116 100.0398 3.6971

e:1:0.074 NA NA

e:1:0.251 256.1097 6.4017

e:1:0.068 NA NA

e:1:0.203 210.9069 4.3334

e:1:0.088 18.4156 2.1509

e:1:0.339 328.8090 11.1895

e:1:0.131 124.7666 3.5324

e:1:0.599 517.7610 27.9397

e:1:0.391 368.4000 14.2786

e:1:0.301 298.5464 9.0339

e:1:0.65 554.0446 31.6358

e:1:0.886 730.1957 51.1850

e:1:0.747 624.2809 39.1322

e:1:0.84 694.2439 47.0005

e:1:0.681 576.2718 33.9613

e:1:0.303 300.1752 9.1447

e:1:0.558 488.7158 25.0762

e:1:0.192 199.6157 3.9844

e:1:0.675 571.9565 33.5063

Sample_results = data.frame(Sample_backfits)

Sample_results$Std..Error = NULL

rownames(Sample_results) = seq(1,36)

Sample_results$Marker = paste0('Marker ', seq(1,36))

The coding punchline

We’ve seen a lot of features and functions in R, many of which may seem like they take a significant amount of thought and effort to use. Recall at the start of today the benefits of using code were reproducibililty, efficiency and automation.

The code above, although fairly involved, is completely reproducible. If you were to return to your analysis 18 months from now, you’d be able to see precisely what had been done, starting with the raw data all the way through to the final results.

Next, we’ll see how code like this makes your analysis more efficient, and highlight the automation potential of such code.

First we need to make our own function, to then use like we’ve been using other functions. This is arguably outside the scope of this introduction to R, but the idea is simple to grasp. A function is a chunk of code that takes data in one end, does something to that data, and then returns the processed data. Or, it’s something that does a task such as create a particular plot. The idea behind functions is to limit the amount of repetition in your code. Below is a very simple example,

times_ten = function(number_in) {

number_out = number_in * 10

return(number_out)

}

This function, called ‘times_ten’, takes in a number, multiplies it by 10, and then returns the result. Let’s run it,

times_ten(2)

[1] 20

Exercise: Custom functions

Alter the code to instead return the factorial of the entered number (e.g. if the entered number was 4, the result would be 24, as the factorial of 4 is 4 x 3 x 2 x 1). Hint, there is a function for this. Run your code with the number 6. What do you get? Note, call your function ‘factorial_out’. Never give a custom function the same name as a built-in one!

Solution

factorial_out = function(number_in) { number_out = factorial(number_in) return(number_out) } factorial_out(6) output: [1] 720

One more concept to understand for this lesson are loops. These are for when you want R to repeat a certain section of code, perhaps changing one or more aspects each time. The main loops in R are while loops and for loops. Let’s take a look at a very simple for-loop,

for(i in seq(1:10)) {

print(paste0('The number is: ', i))

}

[1] "The number is: 1"

[1] "The number is: 2"

[1] "The number is: 3"

[1] "The number is: 4"

[1] "The number is: 5"

[1] "The number is: 6"

[1] "The number is: 7"

[1] "The number is: 8"

[1] "The number is: 9"

[1] "The number is: 10"

Here, we’re asking R to loop through the sequence of numbers, 1 to 10, and for each one, print out the pasted sentence ‘The number is:’ along with ‘i’. In this loop, ‘i’ is the number in the sequence, which increases by 1 each time the loop finishes.

Let’s put this all together. Below is a much larger function that is going to do something very interesting. First, it grabs a list of all the files with a certain keyword in the filename (using the ‘list.files’ function). Then, it goes through each file (using a for-loop), one at a time, performs the 4PL fit, creates a plot, and saves the plot as a png file.

Let’s take a look over the code and the associated comments,

bulk_plots = function(keyword) {

files = list.files(path = "../data/",

pattern = keyword,

full.names = T)

n=1 #for the file number

#iterate over the files in the directory,

for (f in files) {

#read the data,

elisa = read.csv(f)

elisa_stds = elisa[c(1:5),c(1:3)] #based upon the plate definitions

elisa_stds$standards = c(1000, 500, 250, 125, 62.5) #Add a column of standard values

elisa_stds$log_conc = log10(elisa_stds$standards) #Log the standard values

elisa_stds$OD=rowMeans(elisa_stds[,c(2, 3)], na.rm=TRUE) #Calculate row means for the OD column

#fir the curve,

curve_4pl = drm(OD ~ standards,

fct=LL.4(),

data=elisa_stds)

#save the plot to a png file,

png(filename = paste0("../data/", 'plot_', n, '_', Sys.Date(), '.png'))

plot(curve_4pl, col = 'red', main = paste('Plot ', n)) #create the plot

dev.off() #close the png file

n=n+1

}

}

Let’s run it,

bulk_plots('elisa')

Take a look in the folder where the files reside. You should see 10 png files!

Where to go next?

We’ve just seen how to load x10 files, perform x10 curve-fits and produce x10 plots in less than a second. This script could be set to run at a set time each day, if, for example, you had a piece of equipment that was generating raw data files on a regular basis.

Of course, mistakes can still be made when using code instead of mouse-clicks, but crucially, these mistakes are much easier to spot. For very important work, consider getting a colleague to review your code.

R can generate not only images, but processed data-files, mathematical models, full reports in Word or PDF formats, slides, websites and even interactive apps. The level of sophistication is unlimited and can make any routine data processes much quicker, transparent and less prone to human copy-and-paste errors. Any process that you have in your department or company that’s done on a regular basis could and should be performed by code.

Good luck on your R journey!

Key Points

R can be extended in thousands of different ways