Introduction

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

What problems are we solving, and what are we not discussing?

Why do we use Python?

What is parallel programming?

Why can it be hard to write a parallel program?

Objectives

Recognize serial and parallel patterns

Identify problems that can be parallelized

Understand a dependency diagram

Common problems

What problems are we solving?

Ask around what problems participants encountered: “Why did you sign up?”. Specifically: what is the domain science related task that you want to parallelize?

Most problems will fit in one of two categories:

- I wrote this code in Python and it is not fast enough.

- I run this code on my laptop, but the target problem size is bigger than the RAM.

In this course we will show several possible ways of speeding up your program and making it ready to function in parallel. We will be introducing the following modules:

threadingallows different parts of your program to run concurrently on a single computer (with shared memory)daskmakes scalable parallel computing easynumbaspeeds up your Python functions by translating them to optimized machine codememory_profilemonitors memory performanceasyncioPython’s native asynchronous programming

FIXME: Actually explain functional programming & distributed programming More importantly, we will show how to change the design of a program to fit parallel paradigms. This often involves techniques from functional programming.

What we won’t talk about

In this course we will not talk about distributed programming. This is a huge can of worms. It is easy to show simple examples, but depending on the problem, solutions will be wildly different. Dask has a lot of functionality to help you in setting up for running on a network. The important bit is that, once you have made your code suitable for parallel computing, you’ll have the right mind-set to get it to work in a distributed environment.

Overview and rationale

This is an advanced course. Why is it advanced? We (hopefully) saw in the discussion that although many of your problems share similar characteristics, it is the detail that will determine the solution. We all need our algorithms, models, analysis to run in a way that many hands make light work. When such a situation arises with a group of people, we start with a meeting discussing who does what, when do we meet again to sync up, etc. After a while you can get the feeling that all you do is be in meetings. We will see that there are several abstractions that can make our life easier. In large parts this course will use Dask to illustrate these abstractions.

- Vectorized instructions: tell many workers to do the same work on a different piece of data. This

is where

dask.arrayanddask.dataframecome in. We will illustrate this model of working by computing the number Pi later on. - Map/filter/reduce: this is a method where we combine different functionals to create a larger

program. We will use

dask.bagto count the number of unique words in a novel using this formalism. - Task-based parallelization: this may be the most generic abstraction as all the others can be expressed

in terms of tasks or workflows. This is

dask.delayed.

Why Python?

Python is one of most widely used languages to do scientific data analysis, visualization, and even modelling and simulation. The popularity of Python is mainly due to the two pillars of a friendly syntax together with the availability of many high-quality libraries.

It’s not all good news

The flexibility that Python offers comes with a few downsides though:

- Python code typically doesn’t perform as fast as lower-level implementations in C/C++ or Fortran.

- It is not trivial to parallelize Python code to work efficiently on many-core architectures.

This workshop addresses both these issues, with an emphasis on being able to run Python code efficiently (in parallel) on multiple cores.

What is parallel computing?

Dependency diagrams

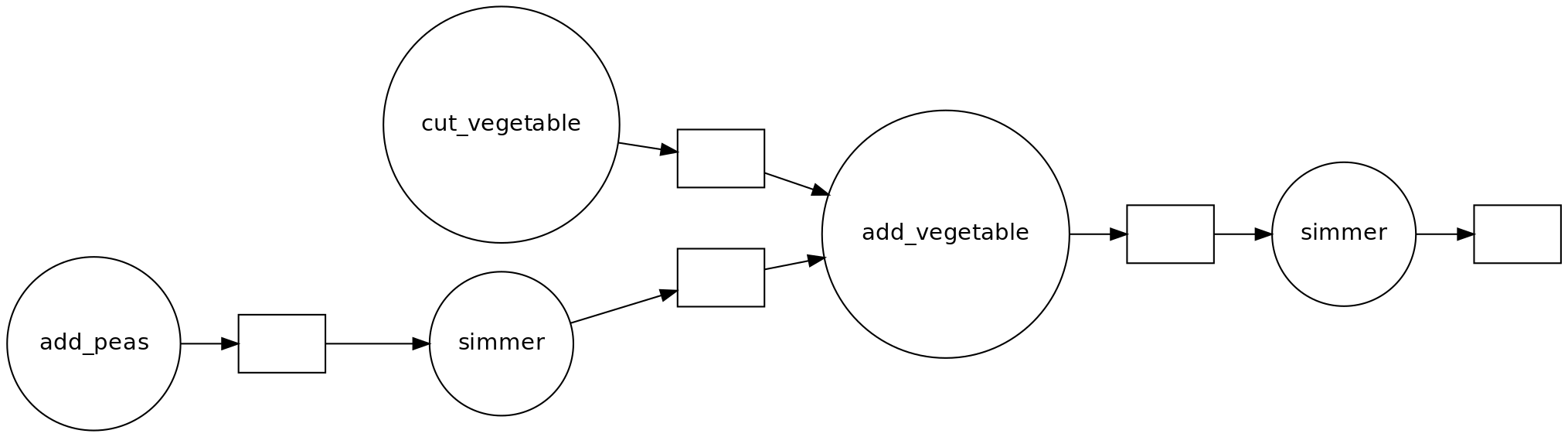

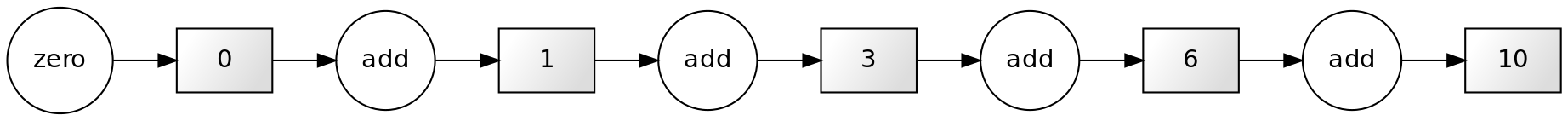

Suppose we have a computation where each step depends on a previous one. We can represent this situation like in the figure below, known as a dependency diagram:

In these diagrams the inputs and outputs of each function are represented as rectangles. The inward and outward arrows indicate their flow. Note that the output of one function can become the input of another one. The diagram above is the typical diagram of a serial computation. If you ever used a loop to update a value, you used serial computation.

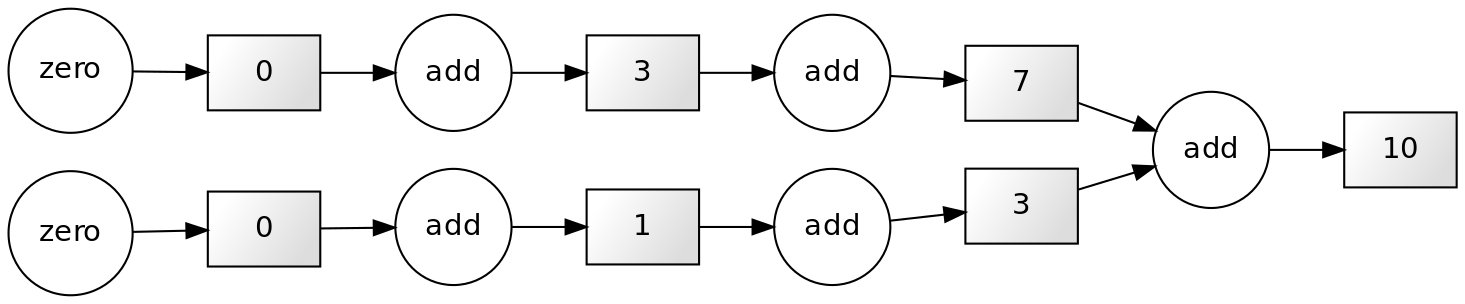

If our computation involves independent work (that is, the results of the application of each function are independent of the results of the application of the rest), we can structure our computation like this:

This scheme corresponds to a parallel computation.

How can parallel computing improve our code execution speed?

Nowadays, most personal computers have 4 or 8 processors (also known as cores). In the diagram above, we can assign each of the three functions to one core, so they can be performed simultaneously.

Do 8 processors work 8 times faster than one?

It may be tempting to think that using eight cores instead of one would multiply the execution speed by eight. For now, it’s ok to use this a first approximation to reality. Later in the course we’ll see that things are actually more complicated than that.

Parallelizable and non-parallelizable tasks

Some tasks are easily parallelizable while others inherently aren’t. However, it might not always be immediately apparent that a task is parallelizable.

FIXME: this may be too much

Let us consider the following piece of code.

x = [1, 2, 3, 4] # Write input

y = 0 # Initialize output

for i in range(len(x)):

y += x[i] # Add each element to the output variable

print(y) # Print output

Note that each successive loop uses the result of the previous loop. In that way, it is dependent on the previous loop. The following dependency diagram makes that clear:

Although we are performing the loops in a serial way in the snippet above, nothing avoids us from performing this calculation in parallel. The following example shows that parts of the computations can be done independently:

x = [1, 2, 4, 4]

chunk1 = x[:2]

chunk2 = x[2:]

sum_1 = sum(chunk1)

sum_2 = sum(chunk2)

result = sum_1 + sum_2

print(result)

The technique for parallelising sums like this is called chunking.

There is a subclass of algorithms where the subtasks are completely independent. These kinds of algorithms are known as embarrassingly parallel, or more friendly naturally or delightfully parallel.

An example of this kind of problem is squaring each element in a list, which can be done like so:

y = [n**2 for n in x]

Each task of squaring a number is independent of all the other elements in the list.

It is important to know that some tasks are fundamentally non-parallelizable.

An example of such an inherently serial algorithm could be the computation of the fibonacci sequence

using the formula Fn=Fn-1 + Fn-2. Each output here depends on the outputs of the two previous loops.

Challenge: Parallellizable and non-parallellizable tasks

Can you think of a task in your domain that is parallelizable? Can you also think of one that is fundamentally non-parallelizable?

Please write your answers in the collaborative document.

Problems versus Algorithms

Often, the parallelizability of a problem depends on its specific implementation. For instance, in our first example of a non-parallelizable task, we mentioned the calculation of the Fibonacci sequence. However, there exists a closed form expression to compute the n-th Fibonacci number.

Last but not least, don’t let the name demotivate you: if your algorithm happens to be embarrassingly parallel, that’s good news! The “embarrassingly” refers to the feeling of “this is great!, how did I not notice before?!”

Challenge: Parallelised Pea Soup

We have the following recipe:

- (1 min) Pour water into a soup pan, add the split peas and bay leaf and bring it to boil.

- (60 min) Remove any foam using a skimmer and let it simmer under a lid for about 60 minutes.

- (15 min) Clean and chop the leek, celeriac, onion, carrot and potato.

- (20 min) Remove the bay leaf, add the vegetables and simmer for 20 more minutes. Stir the soup occasionally.

- (1 day) Leave the soup for one day. Reheat before serving and add a sliced smoked sausage (vegetarian options are also welcome). Season with pepper and salt.

Imagine you’re cooking alone.

- Can you identify potential for parallelisation in this recipe?

- And what if you are cooking with the help of a friend help? Is the soup done any faster?

- Draw a dependency diagram.

Solution

- You can cut vegetables while simmering the split peas.

- If you have help, you can parallelize cutting vegetables further.

- There are two ‘workers’: the cook and the stove.

Shared vs. Distributed memory

FIXME: add text

Key Points

Programs are parallelizable if you can identify independent tasks.

To make programs scalable, you need to chunk the work.

Parallel programming often triggers a redesign; we use different patterns.

Doing work in parallel does not always give a speed-up.