Introduction to Genome Mining

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is Genome Mining?

Objectives

Understand that Natural products are encoded in Biosynthetic Gene Clusters.

Understand that Biosynthetic Gene Clusters can be identified in the genomic material.

Discuss bioinformatic’s good practices with your colleagues.

What is Genome Mining?

In bioinformatics, genomic mining is defined as the computational analysis of nucleotide sequence data based on the comparison and recognition of conserved patterns. Under this definition, any computational method that involves searching for and predicting physiological or metabolic properties is considered part of genomic mining. The specific focus of genomic mining, when applied to natural products (NPs), is centered on the identification of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) of NPs.

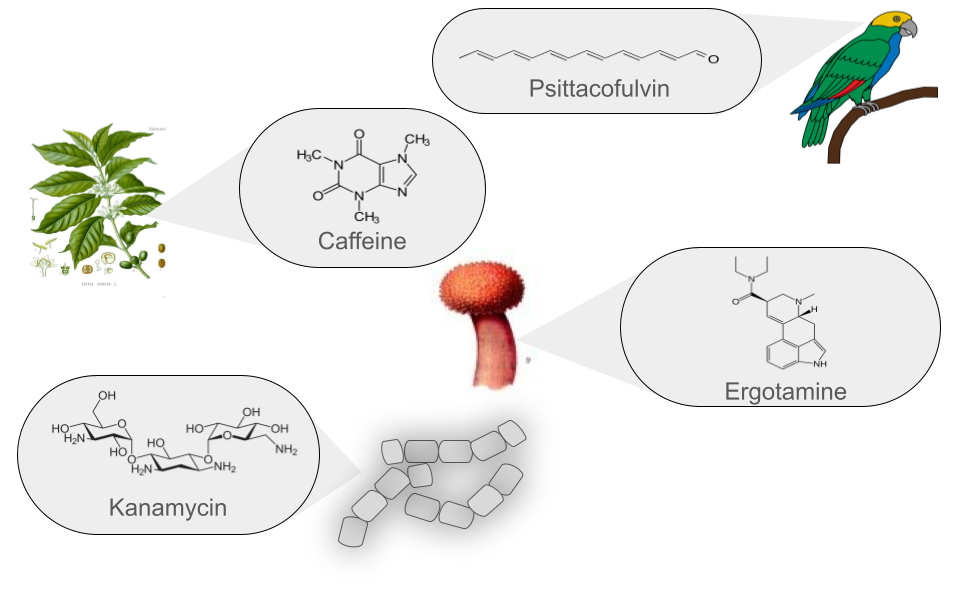

Natural products (NPs) are low molecular weight organic molecules that encompass a wide and diverse range of chemical entities with multiple biological functions. These molecules can be produced by bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals. Natural products (NPs) thus play various roles that can be analyzed from two main perspectives:

- Biological function: This refers to the role the molecule plays in the producing organism.

- Anthropocentric function: This focuses on the utility of NPs for humans, including their use in medicine, agriculture, and other areas.

Currently, more than 126,000 NPs are known to originate from various sources and are classified into six main groups. These groups are defined based on their chemical structure, the enzymes involved in their synthesis, the precursors used, and the final modifications they undergo.

| Class | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Polyketides (PKs) | Polyketides are organic molecules characterized by a repetitive chain of ketone (>C=O) and methylene (>CH2) groups. Their biosynthesis is similar to fatty acid synthesis, which is crucial to their diversity. These versatile molecules are found in bacteria, fungi, plants, and marine organisms. Notable examples include erythromycin, an antibiotic used to treat respiratory infections, and lovastatin, a lipid-lowering drug that reduces cholesterol. In summary, polyketides have a structure based on the repetition of ketone and methylene groups, with significant medical and pharmacological applications. | Erythromycin |

| Non-Ribosomal Peptides (NRPs) | NRPs are a family of natural products that differ from ribosomal peptides due to their non-linear synthesis. Their main structure is based on non-ribosomal modules, which include three key domains: Adenylation, acyl carrier, and condensation domain. Relevant examples include Daptomycin, an antibiotic widely used in various infections. Its NRP structure contributes to its antimicrobial activity. Cyclosporine is an immunosuppressant used in organ transplants. Its NRP structure is crucial to its function. In summary, NRPs feature a non-linear modular structure and play a significant role in medicine and chemical biology. | Daptomycin |

| Ribosomally synthesized and Post-translationally modified Peptides (RiPPs) | RiPPs are a diverse class of natural products of ribosomal origin. These peptides are produced in the ribosomes and then undergo enzymatic modifications after their synthesis. Historically, RiPPs were studied individually, but in 2013, uniform naming guidelines were established for these natural products. RiPPs include examples such as Microcin J25, an antibacterial RiPP produced by Escherichia coli, and Nisin, an antimicrobial RiPP produced by Lactococcus lactis. Their diversity and applications continue to be the subject of ongoing research. | Nisin |

| Saccharides | Saccharides produced in bacterial secondary metabolism are molecules synthesized by various mechanisms and then undergo subsequent enzymatic modifications based on the addition of carbohydrates. Two notable examples are Kanamycin, an aminoglycoside produced by Streptomyces kanamyceticus, used to treat bacterial infections, and Streptomycin, another aminoglycoside produced by Streptomyces griseus, which was one of the first antibiotics used to treat tuberculosis. Although their use has decreased due to bacterial resistance, they remain important in some cases. | Kanamycin |

| Terpenes | Traditionally, terpenes have been considered derivatives of 2-methyl-butadiene, better known as isoprene. Although they have been related to isoprene, terpenes do not directly derive from isoprene, as it has never been found as a natural product. The true precursor of terpenes is mevalonic acid, which comes from acetyl coenzyme A. Terpenes originate through the enzymatic polymerization of two or more isoprene units, assembled and modified in many different ways. Most terpenes have multicentric structures that differ not only in functional group but also in their basic carbon skeleton. These compounds are the main constituent of the essential oils of some plants and flowers, such as lemon and orange trees. They serve various functions in plants, such as being part of chlorophyll, carotenoid pigments, gibberellin and abscisic acid hormones, and increasing the fixation of proteins to cell membranes through isoprenylation. Additionally, terpenes are used in traditional medicine, aromatherapy, and as potential pharmacological agents. Two notable examples of terpenes are limonene, present in citrus peels and used in perfumery and cleaning products, and hopanoids, pentacyclic compounds similar to sterols, whose main function is to confer rigidity to the plasma membrane in prokaryotes. | Diplopterol |

| Alkaloids | Alkaloids are a class of natural, basic organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. They are mainly derived from amino acids and are characterized by their water solubility in acidic pH and solubility in organic solvents at alkaline pH. These compounds are found in various organisms, such as plants, fungi, and bacteria. Alkaloids have a wide range of pharmacological activities, such as Quinine, used against malaria, and Ephedrine, a bronchodilator. Additionally, some alkaloids, such as BE-54017, have an unusual structure, as it presents an indenotryptoline skeleton, rarely observed in other bis-indoles; however, its specific application is not well documented. | BE-54017 |

Genome mining aims to find BGCs

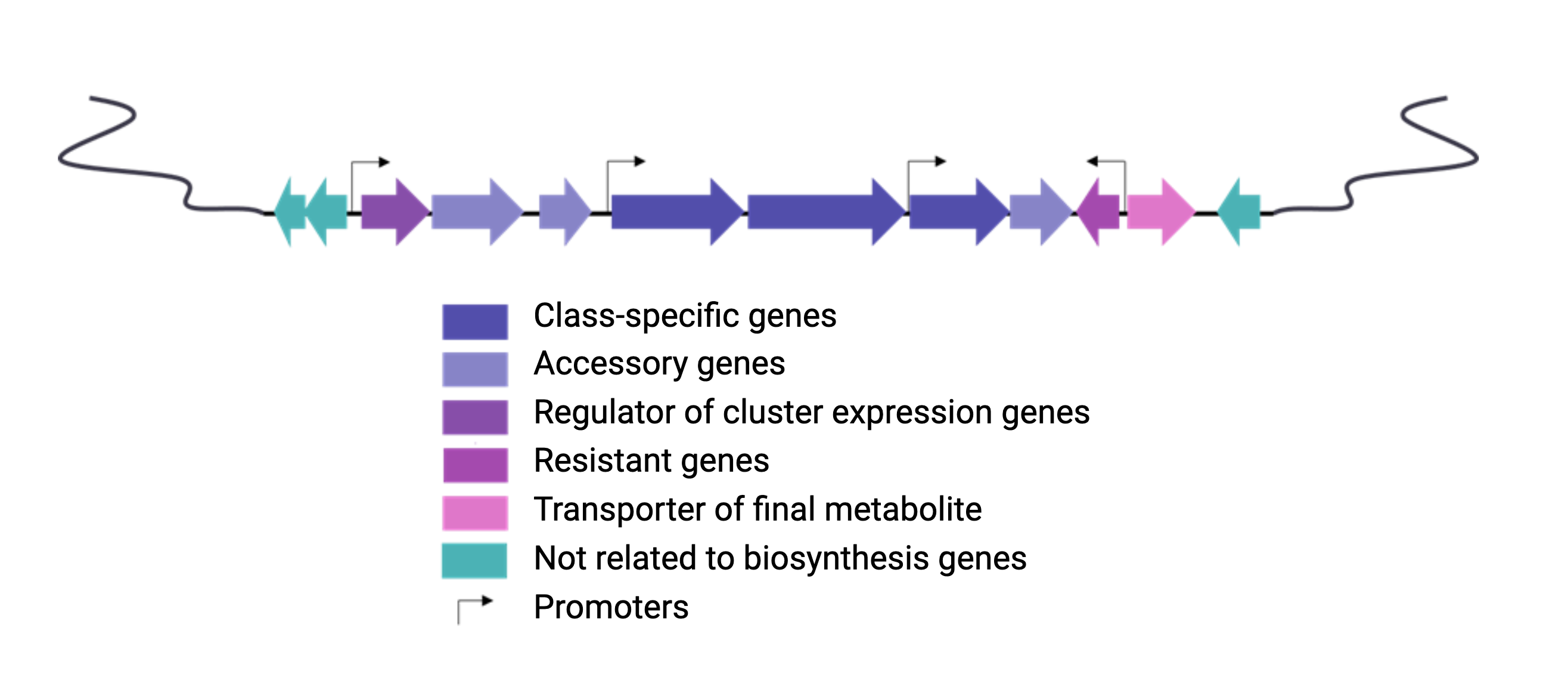

Natural products are encoded in Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) in Bacteria. These BGCs are clusters of genes generally placed together in the same genome region. These include the genes encoding the biosynthetic enzymes and those related to the metabolite’s transport or resistance against antibacterial metabolites. Most BGCs are composed of several types of genes, so genome mining is based on the identification of these genes in a genome.

Each class of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) is distinguished by the types of essential and accessory genes it contains. The most common classes of BGCs for natural products include polyketide synthases (PKSs), non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), and terpenes. For example, non-ribosomal peptides (NRPs) are a class of metabolites characterized by the assembly of amino acid residues or their derivatives, with non-ribosomal peptide synthetases being the enzymes responsible for assembling these molecules. NRPSs are large enzymes organized into modules and domains, similar to other common classes of BGCs. Below, we show you an animation created by Michael W. Mullowney of the biosynthesis of a fictitious NP called “fakeomycin”, which is of the NRPS class with a cyclization domain.

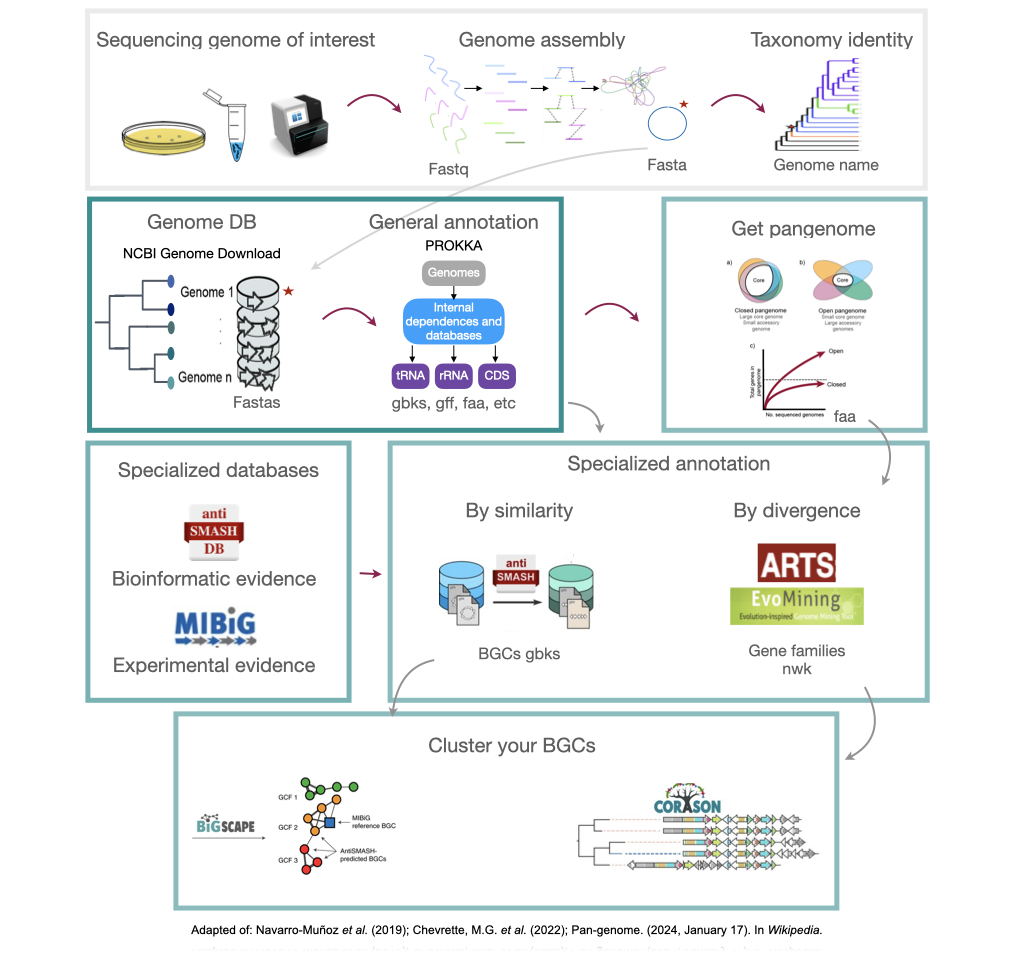

Genome mining consists in analyzing genomes with specialized algorithms designed to find some BGCs. Chemists in the last century diligently characterized some of these clusters. We have extensive databases that contain information about which genes belong to which BGCs and some control sets of genes that do not. The use of genome mining methodologies facilitates the prioritization of BGCs for the search of novel metabolites. Since the era of next-generation sequencing, genomes have been explored as a source for discovering new BGCs.

Chloramphenicol is a known antibiotic produced in a BGC

For example, let’s look into the BGC responsible for chloramphenicol biosynthesis. This is a BGC described for the first time in a Streptomyces venezuelae genome.

Exercise 1: Sort the Steps to Identify BGCs Similar to Clavulanic Acid

Below is a list of steps in disarray that are part of the process of identifying BGCs similar to clavulanic acid. Your task is to logically order them to establish a coherent methodology that allows the effective identification of such BGCs.

Disordered Steps:

a. Annotate the genes within the identified BGCs to predict their function.

b. Compare the identified BGCs against databases of known BGCs to find similarities to clavulanic acid.

c. Extract DNA from samples of interest, such as microorganism-rich soils or specific bacterial cultures.

d. Conduct phylogenetic analysis of the BGCs to explore their evolutionary relationship.

e. Use bioinformatics tools to assemble DNA sequences and detect potential BGCs.

f. Sequence the extracted DNA using next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques.

Solution

- c. Extract DNA from samples of interest, such as microorganism-rich soils or specific bacterial cultures.

- f. Sequence the extracted DNA using next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques.

- e. Use bioinformatics tools to assemble DNA sequences and detect potential BGCs.

- a. Annotate the genes within the identified BGCs to predict their function.

- d. Conduct phylogenetic analysis of the BGCs to explore their evolutionary relationship.

- b. Compare the identified BGCs against databases of known BGCs to find similarities to clavulanic acid.

Planning a genome mining project

Here we will provide tips and tricks to plan and execute a genome mining project. Firstly, choose a set of genomes from taxa. In this lesson we will be working with S. agalactiae genomes (Tettelin et al., 2005). Although this genus is not know for its potential as a Natural products producer, it is good enough to show different approaches to genome mining. Recently, metagenomes have been considered in genome mining studies. Here are some considerations that might be useful as a genome miner:

- Think about a research question before starting to analyze the data.

- Remember, raw metadata should remain intact during all genome mining processes. It could be a good idea to change its file permissions to read-only.

- Gather as much information as metadata of all the genomes you work with.

- All your intermediate steps should be considered temporal and may be removed without risk.

- Save your scripts using a version manager, GitHub for example.

- Share your data in public repositories.

- Give time to make your science repeatable and help your community.

Discussion 1: Describe your project

What are the advantages of documenting your work? Are there other things you can do to make your mining work more reproducible, like commenting on your scripts, etc.?

Solution

Documenting your work helps others (including your future self) understand what you have done and facilitates troubleshooting. To make your work more reproducible, you can detail the code logic by commenting on your scripts, use version control systems like Git, have backups of your scripts, share your data and code with others to facilitate feedback, and follow standardized workflows or protocols like those taught in this lesson. You can also name your files properly with a consistent format, structure your directories well, and back up your work regularly. Additionally, keeping a log (or “bitácora”) can serve as a tutorial for your future self, making it easier to understand your work later on.

Starting a genome mining project

Once you have chosen your set of genomes, you need to annotate the sequences. The process of genome annotation needs two steps. First, a gene calling approach (structural annotation), which looks for CDS or RNAs within the DNA sequences. Once these features have been detected, you need to assign a function for each CDS (functional annotation). This is usually done through comparison against protein databases. There are tens of bioinformatics tools to annotate genomes, but some of the most broadly used are; RAST (Aziz et al. 2008), and Prokka (Seeman, 2014). Here, we will start the genome mining lesson with S. agalactiae genomes already annotated by Prokka. You can download this data from this repository. The annotated genomes are written in GeneBank format (extension “.gbk”). To learn more about the basic annotation of genomes, see the lesson named “Pangenome Analysis in Prokaryotes: Annotating Genomic Data”. These files are also accessible in the… Insert introduction related to the access to the server??

References

- Aziz, R. K., Bartels, D., Best, A. A., DeJongh, M., Disz, T., Edwards, R. A., … & Zagnitko, O. (2008). The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC genomics, 9(1), 1-15.

- Seemann, T. (2014). Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics, 30(14), 2068-2069.

- Tettelin, H., Masignani, V., Cieslewicz, M. J., Donati, C., Medini, D., Ward, N. L., … & Fraser, C. M. (2005). Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial “pan-genome”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(39), 13950-13955.

- Nett, Markus (2014). Kinghorn, A. D., ed. Genome Mining: Concept and Strategies for Natural Product Discovery. Springer International Publishing. pp. 199-245. ISBN 978-3-319-04900-7. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-04900-7_4.

- Katz, Leonard; Baltz, Richard H. «Natural product discovery: past, present, and future». Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 43 (2-3): 155-176. ISSN 1476-5535. doi:10.1007/s10295-015-1723-5.

- Mejía Ponce, Paulina M.(2017). Análisis filogenético de familias de enzimas que utilizan tRNA, indicios para el descubrimiento de productos naturales ocultos en Actinobacteria. Tesis (M.C.)–Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del I.P.N. Unidad Irapuato. Laboratorio Nacional de Genómica para la Biodiversidad. 2020-08-13T02:57:32Z.

Key Points

Natural products are encoded in Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)

Genome mining describes the exploitation of genomic information with specialized algorithms intended to discover and study BGCs