Markov chain Monte Carlo

Last updated on 2025-11-10 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 63 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How does Stan generate the posterior samples?

Objectives

Learn

- the basic idea of the Metropolis-Hasting algorithm.

- how to assess Markov chain Monte Carlo convergence.

- how to implement a random walk Metropolis-Hasting algorithm.

The standard solution to fitting probabilistic models is to generate random samples from the posterior distribution. In the previous episode, we learned how to generate posterior samples using Stan without knowing how the samples are generated. In this episode, we’ll study Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, which are the class of algorithms Stan uses under the hood.

Metropolis-Hastings algorithm

MCMC methods draw samples from the posterior distribution by constructing sequences (chains) of values in the parameter space that ultimately converge to the posterior. While there are other variants of MCMC, on this course we will mainly focus on the Metropolis-Hasting (MH) algorithm outlined below. As this algorithm is ran long enough, convergence to posterior (or to other specified target density) is guaranteed. This means that that if the chain is run long enough, the samples will eventually start approximating the posterior distribution.

A chain starts is initialized at value \(\theta^{0}\), which can be manually set or random. The only precondition is that the target distribution has positive mass at the location, \(p(\theta^{0} | X) > 0\). Then, a proposal \(\theta^*\) for the next value is generated from a proposal distribution \(T_i\). An often-used solution is the normal distribution centered at the current value, \(\theta^* \sim N(\theta^{i}, \sigma^2)\). This is where the term “Markov chain” comes from, the value of each element depends only on the previous one.

Next, the proposal \(\theta^*\) is either accepted or rejected. If each proposal was accepted, the sequence would simply be a random walk in the parameter space and would not approximate the posterior to any degree. The rule that determines the acceptance should reflect this; proposals towards higher posterior densities should be favored over proposals toward low density areas. The solution is to compute the ratio

\[r = \frac{p(\theta^* | X) / T_i(\theta^* | \theta^{i})}{p(\theta^i | X) / T_i(\theta^{i} | \theta^{*})},\] and use is as the probability to move to the proposed value. In other words, the next element in the chain is \(\theta^{i+1} = \theta^*\) with probability \(\min(r, 1)\). If the proposal is not accepted the chain stays at the current value, \(\theta^{i+1} = \theta^{i}.\) This approach induces directional randomness in the chain; proposals towards higher density areas are generally accepted but transitions away from it are also possible. In situations where the transition density is symmetric, such as with the normal distribution, \(r\) reduces simply to the ratio of the posterior values, and all proposals toward higher posterior density areas are accepted.

Example: Banana distribution

Let’s implement the MH algorithm and use it to generate posterior samples from the following statistical model:

\[X \sim N(\theta_1 + \theta_2^2, 1) \\ \theta_1, \theta_2 \sim N(0, 1),\]

where \(X\) is univariate data and \(\theta_1, \theta_2\) the parameters.

Helper functions

We begin by writing some helper functions that carry out the incremental steps of the MH algorithm.

First, we need to be able to generate the proposals. Let’s use the

two-dimensional normal with identity covariance scaled by a scalar

jump_scale.

R

set.seed(12)

generate_proposal <- function(pars_now, jump_scale = 0.1) {

n_pars <- length(pars_now)

# Random draw from multivariate normal

theta_star <- mvtnorm::rmvnorm(1,

mean = pars_now,

sigma = jump_scale*diag(n_pars))

return(theta_star)

}

Running MH also requires computing the (unnormalized) posterior

density at the proposed parameter values. This function returns the log

posterior value at the location pars. The density is

computed on log scale to avoid issues with numerical precision.

R

get_log_target_value <- function(X, pars) {

# log(likelihood)

sum(

dnorm(X,

mean = pars[1] + pars[2]^2,

sd = 1,

log = TRUE)

) +

# log(prior)

dnorm(pars[1], 0, 1, log = TRUE) +

dnorm(pars[2], 0, 1, log = TRUE)

}

Then, we’ll write a function that computes the acceptance ratio \(r\). Since the proposal is symmetric, the expression reduces to the ratio of the posterior densities of the proposed and current parameter values. Notice that a ratio on a log scale is equal to the difference of logarithms.

R

# Compute ratio

get_ratio <- function(X, pars_now, pars_proposal) {

r <- exp(

get_log_target_value(X, pars_proposal) -

get_log_target_value(X, pars_now)

)

return(r)

}

Finally, we can wrap the helpers in a function that loops over the algorithm steps.

R

# Sampler

MH_sampler <- function(X, # Data

inits, # Initial values

n_samples = 1000, # Number of iterations

jump_scale = 0.1 # Proposal jump variance

) {

# Matrix for samples

pars <- matrix(nrow = n_samples, ncol = length(inits))

# Set initial values

pars[1, ] <- inits

# Generate samples

for(i in 2:n_samples) {

# Current parameters

pars_now <- pars[i-1, ]

# Proposal

pars_proposal <- generate_proposal(pars_now, jump_scale)

# Ratio

r <- get_ratio(X, pars_now, pars_proposal)

r <- min(1, r)

# Does the sampler move?

move <- sample(x = c(TRUE, FALSE),

size = 1,

prob = c(r, 1-r))

# OR:

# move <- runif(n = 1, min = 0, max = 1) <= r

if(move) {

pars[i, ] <- pars_proposal

} else {

pars[i, ] <- pars_now

}

}

pars <- data.frame(pars)

return(pars)

}

Run MH

Now we can try out our MH implementation. Let’s use the simulated

data points stored in vector X:

R

X <- c(3.78, 2.76, 2.84, 2.92, 1.3, 3.93, 3.69, 2.28, 2.81, 0.71)

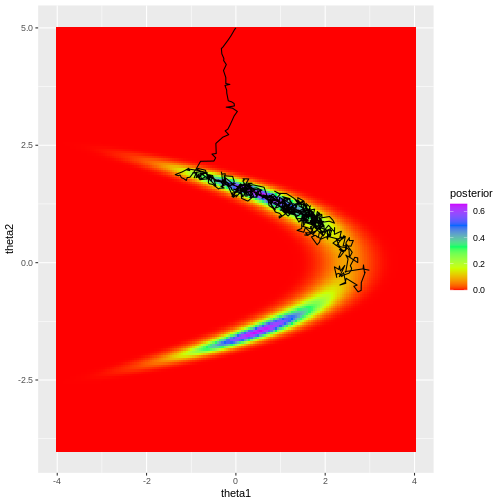

We’ll generate 1000 samples with initial value (0, 5) and jump scale 0.01. The trajectory of samples is plotted over the posterior density computed with the grid approximation.

R

# Draw samples

samples1 <- MH_sampler(X,

inits = c(0, 5),

n_samples = 1000,

jump_scale = 0.01)

colnames(samples1) <- c("theta1", "theta2")

# Add column for sample index

samples1$sample <- 1:nrow(samples1)

# Grid approximation

delta <- 0.05

df_grid <- expand.grid(seq(-4, 4, by = delta),

seq(-4, 5, by = delta)) %>%

set_colnames(c("theta1", "theta2"))

for(i in 1:nrow(df_grid)) {

df_grid[i, "likelihood"] <- prod(

dnorm(X,

df_grid[i, "theta1"] + df_grid[i, "theta2"]^2,

1)

)

}

df_grid <- df_grid %>%

mutate(prior = dnorm(theta1, 0, 1)*dnorm(theta2, 0, 1)) %>%

mutate(posterior = prior*likelihood) %>%

mutate(posterior = posterior / (sum(posterior)*delta^2))

# Plot

p_grid <- ggplot() +

geom_tile(data = df_grid,

aes(x = theta1, y = theta2, fill = posterior)) +

scale_fill_gradientn(colours = rainbow(5))

# Plot joint posterior samples

p_MH1 <- p_grid +

geom_path(data = samples1,

aes(x = theta1, y = theta2))

print(p_MH1)

Looking at the figure, a few observations become evident. Firstly, despite the chosen initial value being moderately far from the high-density areas of the posterior, the algorithm quickly converges to the target region. This rapid convergence is due to the fact that proposals toward higher density areas are favored, in fact they are always accepted when using normal density proposals. However, it’s important to note that such swift convergence is not guaranteed in all scenarios. In cases with a high number of model parameters, there’s an increased likelihood of the sampler taking ‘wrong’ directions. The samples before convergence introduce bias to the posterior approximation.

Secondly, the posterior is not fully explored; no samples are generated from the lower mode in the figure. This highlights a crucial point: even if the sampler has converged, it doesn’t guarantee that the drawn samples provide a representative picture of the target.

Challenge

Consider how you could address the two issues raised above:

- Initial unconverged samples introduce a bias.

- The sampler may not have explored the target distribution properly.

Try different proposal distributions variances in the MCMC example

above by changing jump_scale. How does this affect the

inference and convergence? Why?

Assessing convergence

Although convergence of MCMC is theoretically guaranteed, in practice, this is not always the case. Monitoring convergence is crucial whenever MCMC is utilized to ensure the reliability of recovered results.

Depending on the model used, initial values, amount of data, among other factors, can cause convergence issues. Earlier, we mentioned two common complications, and here we will list a few more, along with actions that can alleviate the issues.

Slow convergence can occur when initial values of the chain are far from most of the target mass, resulting in early iterations biasing the approximation. Another cause for slow convergence is that the proposals are not far enough from the current value, and the sampler moves too slowly.

Incomplete exploration: This means that the sampler doesn’t spend enough time in all significant posterior areas.

A large proportion of the proposals is rejected. When the proposal distribution generates proposals too far from the current value, the proposals are rejected and the sampler stands still for many iterations. This leads to inefficiency.

Sample autocorrelation: Consecutive samples are close to each other. Ideally, we’d like to generate independent samples from the target. High sample autocorrelation can be caused by several factors, including the ones mentioned in the previous points.

These issues can be remedied with:

Running multiple long chains with distinct or random initial values.

Discarding the early proportion of the chain as warm-up.

Setting an appropriate proposal distribution.

It also important to be able to monitor whether the sampler has converged. This can be done with statistics, such as effective sample size and \(\hat{R}\). Effective sample size estimates how many independent samples have been generated. Ideally, this number should be close to the total number of iterations the sampler has been ran for. \(\hat{R}\) on the other hand measures chain mixing, that is, how well the chains agree with each other. It is computed by comparing the variance within each chain to the total variance of all samples. Usually, values of \(\hat{R} > 1.1\) are considered as signaling convergence issues. However, the Stan development team recommends using 1.05 as the limit.

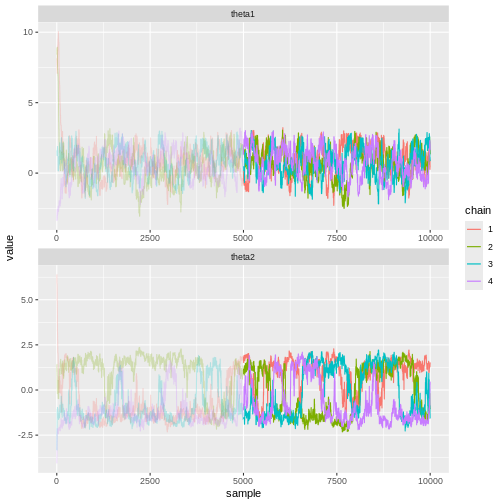

Besides statistics, visually evaluating the samples can be useful. Trace plots refer to graphs where the marginal posterior samples are plotted against sample index. Trace plots can be used to investigate convergence and mixing properties, and can reveal, for example, multimodality.

In Stan, many of the above-mentioned points have been automatized. By default, Stan runs 4 chains with 2000 iterations each, and discards the initial 50% as warm-up. Moreover, it computes \(\hat{R}\), effective sample size, and other statistics and throws warnings in case of issues.

Example continued

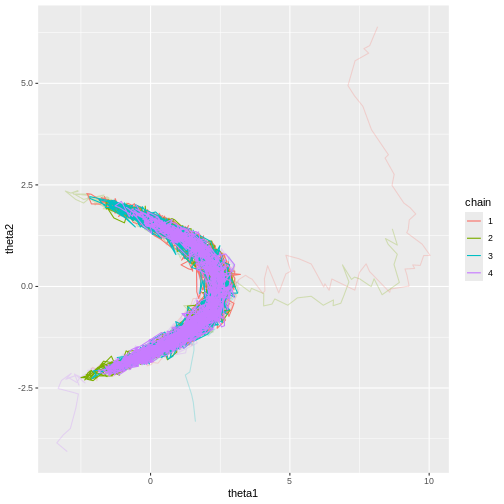

In light of the above information, let’s re-fit the model of the previous example. Now, we’ll run 4 chains with random initial values, 10000 samples each, and discard the first 50% of each chain as warm-up. We’ll use 0.1 as the proposal variance.

R

# Number of chains

n_chains <- 4

# Number of samples

n_samples <- 10000

# Initial warmup proportion

warmup <- 0.5

samples2 <- lapply(1:n_chains, function(i) {

# Use random initial values

inits <- rnorm(2, 0, 5)

chain <- MH_sampler(X, inits = inits,

n_samples = n_samples,

jump_scale = 0.1)

# Wrangle

colnames(chain) <- c("theta1", "theta2")

chain$sample <- 1:nrow(chain)

chain$chain <- as.factor(i)

chain[1:round(warmup*n_samples), "warmup"] <- TRUE

chain[(round(warmup*n_samples)+1):n_samples, "warmup"] <- FALSE

return(chain)

}) %>%

do.call(rbind, .)

Now it’s evident that the sample trajectories explore the entire posterior distribution:

R

# Plot

p_joint_2 <- ggplot() +

# Warm-up samples

geom_path(data = samples2 %>%

filter(warmup == TRUE),

aes(theta1, theta2, color = chain),

alpha = 0.25) +

# Post-warm-up samples

geom_path(data = samples2 %>%

filter(warmup == FALSE),

aes(theta1, theta2, color = chain))

print(p_joint_2)

Let’s see what the trace plots look like. Generally, we’d want to see the samples randomly scattered around a mean value. For \(\theta_1\) this is more or less the case, although there some autocorrelation is apparent. With \(\theta_2\) we can see that the chains have mixed as they explore the same parameter ranges. However, the bimodality of the posterior is quite apparent. The \(\hat{R}\) statistics are 1.0082279 and 1.1065365 for \(\theta_1\) and \(\theta_2\), respectively.

R

# Trace plots

p_trace_2 <- ggplot() +

geom_line(data = samples2 %>%

filter(warmup == TRUE) %>%

gather(key = "parameter",

value = "value",

-c("sample", "chain", "warmup")),

aes(x = sample, y = value, color = chain),

alpha = 0.25) +

geom_line(data = samples2 %>%

filter(warmup == FALSE) %>%

gather(key = "parameter",

value = "value",

-c("sample", "chain", "warmup")),

aes(x = sample, y = value, color = chain)) +

facet_wrap(~parameter,

ncol = 1,

scales = "free")

print(p_trace_2)

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo

Stan uses a variant of the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm called Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC; or actually a variant HMC). The defining feature is the elaborate scheme it uses to generate proposals. Briefly, the idea is to simulate the dynamics of a particle moving in a potential landscape defined by the posterior. At each iteration, the particle is given a random momentum vector and then its dynamics are simulated forward for some time. The end of the trajectory is then taken as the proposal value.

Compared to the random walk Metropolis-Hastings we implemented in this episode, HMC is very efficient. The main advantages of HMC is its ability to explore high-dimensional spaces more effectively, making it especially useful in complex models with many parameters.

A type of convergence criterion exclusive to HMC is the divergent transition. In a region of the parameter space where the posterior has high curvature, the simulated particle dynamics can produce spurious transitions which do not represent the posterior accurately. Such transitions are called divergent and signal that the particular area of parameter space is not explored accurately. Stan provides information about divergent transitions automatically.

- Markov chain Monte Carlo methods can be used to generate samples from a posterior distribution.

- Values of the chain are generated from a proposal distribution.

- Proposals towards higher areas of the target distribution are accepted with higher probability.

- MCMC convergence should always be monitored.

Reading

See interactive visualization of different MCMC algorithms: https://chi-feng.github.io/mcmc-demo/app.html

Bayesian Data Analysis (3rd ed.): Ch. 11-12

Statistical Rethinking (2nd ed.): Ch. 9

Bayes Rules!: Ch. 6-7