t-tests in practice

Overview

Teaching: 0 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How are t-tests used in practice?

Objectives

t-tests in Practice

Introduction

We will now demonstrate how to obtain a p-value in practice. We begin by loading experimental data and walking you through the steps used to form a t-statistic and compute a p-value. We can perform this task with just a few lines of code (go to the end of this section to see them). However, to understand the concepts, we will construct a t-statistic from “scratch”.

Read in and prepare data

We start by reading in the data. A first important step is to identify which rows are associated with treatment and control, and to compute the difference in mean.

fWeights <- read.csv(file = "../data/femaleMiceWeights.csv") # we read this data in earlier

control <- filter(fWeights, Diet=="chow") %>%

select(Bodyweight) %>%

unlist

treatment <- filter(fWeights, Diet=="hf") %>%

select(Bodyweight) %>%

unlist

diff <- mean(treatment) - mean(control)

print(diff)

[1] 3.020833

We are asked to report a p-value. What do we do? We learned that diff,

referred to as the observed effect size, is a random variable. We also learned

that under the null hypothesis, the mean of the distribution of diff is 0.

What about the standard error? We also learned that the standard error of this

random variable is the population standard deviation divided by the square root

of the sample size:

We use the sample standard deviation as an estimate of the population

standard deviation. In R, we simply use the sd function and the SE is:

sd(control)/sqrt(length(control))

[1] 0.8725323

This is the SE of the sample average, but we actually want the SE of diff. We

saw how statistical theory tells us that the variance of the difference of two

random variables is the sum of its variances, so we compute the variance and

take the square root:

se <- sqrt(

var(treatment)/length(treatment) +

var(control)/length(control)

)

Statistical theory tells us that if we divide a random variable by its SE, we get a new random variable with an SE of 1.

tstat <- diff/se

This ratio is what we call the t-statistic. It’s the ratio of two random variables and thus a random variable. Once we know the distribution of this random variable, we can then easily compute a p-value.

As explained in the previous section, the CLT tells us that for large sample sizes, both sample averages mean(treatment) and mean(control) are normal. Statistical theory tells us that the difference of two normally distributed random variables is again normal, so CLT tells us that tstat is approximately normal with mean 0 (the null hypothesis) and SD 1 (we divided by its SE).

So now to calculate a p-value all we need to do is ask: how often does a

normally distributed random variable exceed diff? R has a built-in function,

pnorm, to answer this specific question. pnorm(a) returns the probability

that a random variable following the standard normal distribution falls below

a. To obtain the probability that it is larger than a, we simply use

1-pnorm(a). We want to know the probability of seeing something as extreme as

diff: either smaller (more negative) than -abs(diff) or larger than

abs(diff). We call these two regions “tails” and calculate their size:

righttail <- 1 - pnorm(abs(tstat))

lefttail <- pnorm(-abs(tstat))

pval <- lefttail + righttail

print(pval)

[1] 0.0398622

In this case, the p-value is smaller than 0.05 and using the conventional cutoff of 0.05, we would call the difference statistically significant.

Now there is a problem. CLT works for large samples, but is 12 large enough? A rule of thumb for CLT is that 30 is a large enough sample size (but this is just a rule of thumb). The p-value we computed is only a valid approximation if the assumptions hold, which do not seem to be the case here. However, there is another option other than using CLT.

The t-distribution in Practice

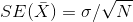

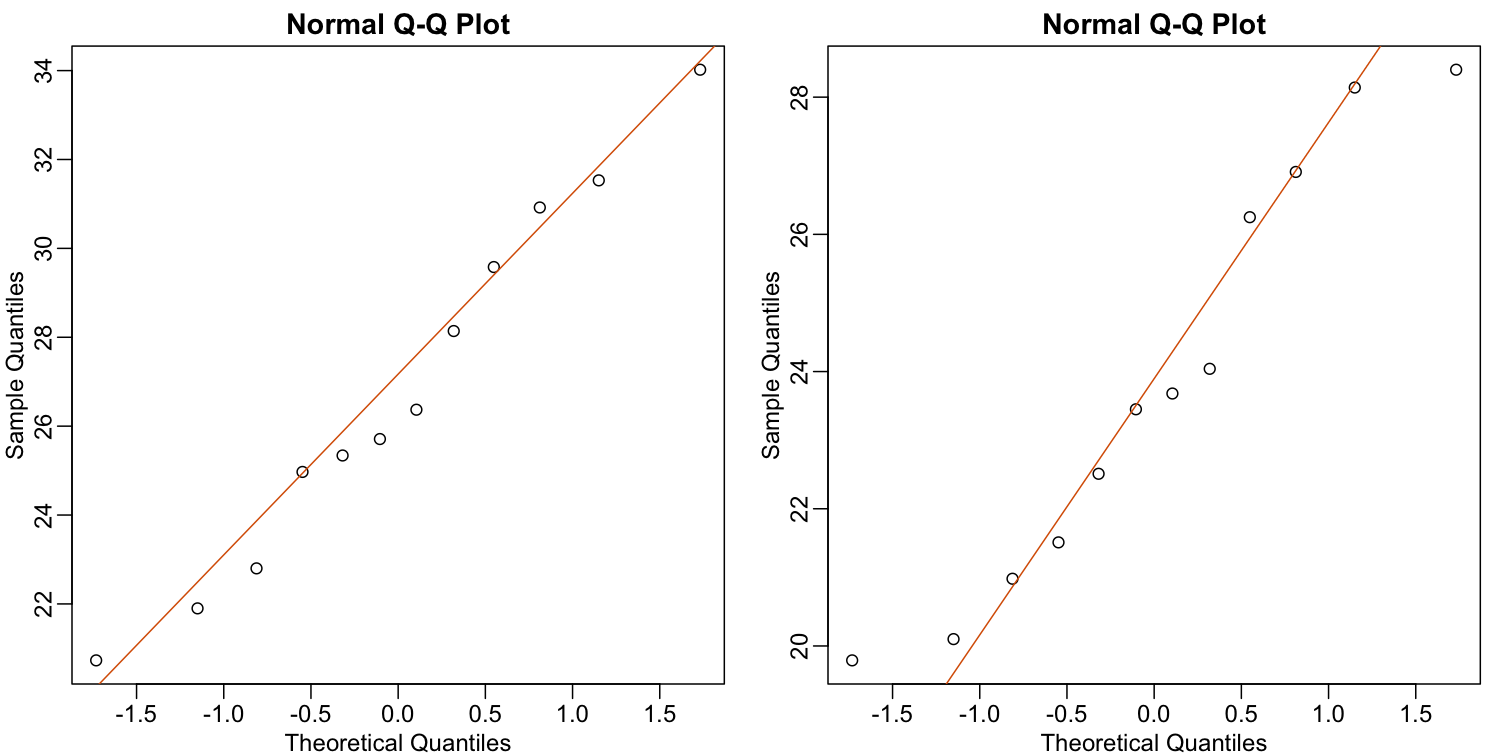

As described earlier, statistical theory offers another useful result. If the distribution of the population is normal, then we can work out the exact distribution of the t-statistic without the need for the CLT. This is a big “if” given that, with small samples, it is hard to check if the population is normal. But for something like weight, we suspect that the population distribution is likely well approximated by normal and that we can use this approximation. Furthermore, we can look at a qq-plot for the samples. This shows that the approximation is at least close:

library(rafalib)

Attaching package: 'rafalib'

The following object is masked from 'package:remotes':

install_bioc

mypar(1,2)

qqnorm(treatment)

qqline(treatment, col=2)

qqnorm(control)

qqline(control, col=2)

If we use this approximation, then statistical theory tells us that the

distribution of the random variable tstat follows a t-distribution. This is a

much more complicated distribution than the normal. The t-distribution has a

location parameter like the normal and another parameter called

degrees of freedom. R has a nice function that actually computes everything

for us.

t.test(treatment, control)

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: treatment and control

t = 2.0552, df = 20.236, p-value = 0.053

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-0.04296563 6.08463229

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

26.83417 23.81333

To see just the p-value, we can use the $ extractor:

result <- t.test(treatment,control)

result$p.value

[1] 0.05299888

The p-value is slightly bigger now. This is to be expected because our CLT

approximation considered the denominator of tstat practically fixed

(with large samples it practically is), while the t-distribution approximation

takes into account that the denominator (the standard error of the difference)

is a random variable. The smaller the sample size, the more the denominator

varies.

It may be confusing that one approximation gave us one p-value and another gave us another, because we expect there to be just one answer. However, this is not uncommon in data analysis. We used different assumptions, different approximations, and therefore we obtained different results.

Later, in the power calculation section, we will describe type I and type II errors. As a preview, we will point out that the test based on the CLT approximation is more likely to incorrectly reject the null hypothesis (a false positive), while the t-distribution is more likely to incorrectly accept the null hypothesis (false negative).

Running the t-test in practice

Now that we have gone over the concepts, we can show the relatively simple code that one would use to actually compute a t-test:

control <- filter(fWeights, Diet=="chow") %>%

select(Bodyweight) %>%

unlist

treatment <- filter(fWeights, Diet=="hf") %>%

select(Bodyweight) %>%

unlist

t.test(treatment, control)

Welch Two Sample t-test

data: treatment and control

t = 2.0552, df = 20.236, p-value = 0.053

alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

95 percent confidence interval:

-0.04296563 6.08463229

sample estimates:

mean of x mean of y

26.83417 23.81333

The arguments to t.test can be of type data.frame and thus we do not need to

unlist them into numeric objects.

Key Points

.

.

.

.