Python Scripts and Modules

Last updated on 2024-04-16 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 22 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is a ‘module’ in Python? How does this differ from a ‘script’?

- What are the benefits of modularising our Python code?

Objectives

- Introduce the example library used in this lesson.

- Understand the limitations of scripts.

- Understand what happens when we

importsomething. - Learn how to convert a simple script into a reusable module.

Python as a Scripting Language

Python is frequently used as a scripting language by scientists and engineers due to its expressiveness, simplicity, and its rich ecosystem of third-party libraries. There isn’t a hard line between a scripting language and a non-scripting language, but some differences include:

- Scripts are not compiled to an executable or library object (such as

.soor.dll) before use, and are instead interpreted directly from the source code. A non-scripting language, such as C++, must be compiled to machine code before it can be used. - Scripts must be run using some other compiled program, such as

pythonorbash. - Scripts are typically short programs that leverage the power of complex libraries to accomplish some task. They focus more on gluing together existing tools than performing their own low-level computations.

Python is a very general-purpose language, and it meets the criteria of both a scripting language and a non-scripting language depending on how we choose to use it:

- Python can be run as an interactive session simply by calling

pythonat the command line. This is typical of a scripting language. - It is possible to write a linear series of Python expressions in a file, and run this using the Python interpretter –again, like a scripting language.

- Python code can be bundled in modules and packages

which can then be

import-ed into other Python programs/scripts. These are typically pre-compiled into ‘bytecode’ to improve performance. This is closer to the behaviour of a fully compiled language.

Typically, a Python project will begin as something that is inarguably a ‘script’, but as it develops it will take on the character of a ‘program’. A single file containing a linear series of commands may develop into a module of reusable functions, and this may develop further into a package of related modules. Developing our software in this way allows our programs to grow in complexity in a much more sustainable manner, and grants much more flexibility to how users can interact with our code.

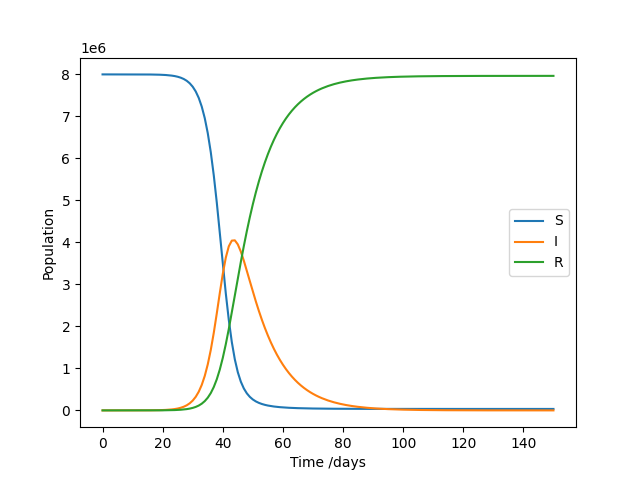

Throughout this course, we’ll develop an example library that might be used for epidemiology modelling, though it isn’t necessary to understand how this works in order to follow the course. We’ll begin where many new Python projects start: with a simple script. This one solves a SIR model, which models the number of Susceptible, Infected, and Recovered individuals as a pathogen spreads through a population. The general pattern of the code – set up inputs, solve a problem, plot the results – should be familiar to those working in a data-oriented field. It uses the popular plotting library Matplotlib to generate a figure.

It isn’t necessary to dwell on the details of the script. It’s only being used as an example of the sort of script the students might be familiar with.

PYTHON

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Inputs

# Total number of susceptible people at the start of an outbreak

pop_size = 8000000

# Average no. of new infections per infected person per day

beta = 0.5

# Inverse of the average number of days taken to recover

gamma = 0.1

# Number of days to run the simulation for

days = 150

# Number of infected people at the start of the simulation

I_0 = 10

# Initialise data

S = [] # Number of susceptible people each day

I = [] # Number of infected people each day

R = [] # Number of recovered people each day

S.append(pop_size - I_0)

I.append(I_0)

R.append(0)

# Solve model

for i in range(days):

# Get rate of change of S, I, and R

dS = - beta * S[i] * I[i] / pop_size

dR = gamma * I[i]

dI = -(dS + dR)

# Get values on next day

S.append(S[i] + dS)

I.append(I[i] + dI)

R.append(R[i] + dR)

# Plot results

plt.plot(range(len(S)), S, label="S")

plt.plot(range(len(I)), I, label="I")

plt.plot(range(len(R)), R, label="R")

plt.xlabel("Time /days")

plt.ylabel("Population")

plt.legend()

plt.show()If we save this script to the file SIR_model_script.py,

it can then be run from the command line as follows:

If everything works as expected, it should produce the following result:

So far so good, but there are some limitations to this coding style.

There are many possible answers to this. Here are some examples:

- If the user wants to change the model inputs, they have to open the script file and modify some lines of code before running again. This is difficult to automate and it’s possible that the user might overwrite something they didn’t intend to.

- If we wish to expand on this functionality or do something different with the output data, we must either overwrite our original script, or copy the code across to a new scipt. If we choose to copy the script, it would take a lot of effort to update all versions every time we wish to adjust the core routine, and this is likely to introduce bugs.

- The user must know where the script is stored on their system, navigate to that directory, and call it from there. This makes it challenging to string scripts together to make more complex programs.

It’s important to note that there’s nothing strictly wrong

with writing scripts in this way, and it’s often a good starting point

for a new project. However, as we develop our project further, we might

find it useful to bundle up the reusable bits of our code into a

module that we can import from other Python

programs, just as we import-ed Matplotlib in our own

script.

What is a ‘Module’?

A module is simply any file containing Python statements,

so, technically, the script we defined above is already a module. The

name of a module is the same as the file name, only without the

.py extension. If we were to open a new Python interpretter

session and call the following:

then the script would run as if we’d run it from the command line.

However, the variables we defined in the script will be accessible

within the namespace SIR_model_script:

The current namespace includes all of the objects defined in our

interpretter session, plus all built-in Python functions and types. When

we import our script, we add the name of the script to the

current namespace, but not the variables defined within it; those are

defined within the scope of SIR_model_script, and

are only accessible using the dot operator. If we wanted to bring

everything within the script to the current namespace, but not the

module itself, we can instead call:

Alternatively, if we only want a few objects brought into the current namespace, we can use:

The dangers offrom module import *

Using from module import * is considered harmful by many

developers, as objects can be unintentionally overwritten if there are

any name clashes between modules. It can also make it difficult for

people reading you code to tell which modules your functions and classes

have come from. In general, it’s better to be explicit about what you’re

import-ing.

It is also possible to assign an alias to a module name using the

as keyword:

Something to note about import is that it runs the code

found within the module only the first time it is imported, so if we

were to import our script multiple times, it would only create a plot

once.

While we’ve shown that our script is importable, so far it doesn’t seem to provide many advantages over simply running it on the command line. The next section will explain what features can make a module more versatile and useful.

The result is 15, as the second import does not run the

code in my_module.py, and therefore

my_module.x is not reset back to 10.

Making a Reusable Module

A good Python module will tend to do the following:

- Define functions, classes and constants that the user might want to use.

- Not rely on global variables (those defined within the module but not inside of functions/classes), except in a few scenarios where it only makes sense for a single instance of the an object to exist.

- Avoid performing runtime calculations at the

importstage.

Most Python modules shouldn’t do anything if we try to run them from

the command line, and instead they should provide

import-able tools that can be used in the Python

interpretter, by other Python modules, or by dedicated scripts. We’ll

see later how to write a reusable Python module that doubles as a

runnable script.

Most scripts can be converted into reusable modules using the following steps:

- Identify each major stage of our data processing. Examples may include reading in data, running a model, processing results, creating plots, etc.

- For each stage, identify what data is an input, and what is an output.

- Bundle each processing stage into a function that takes the input data as arguments and returns the output data.

For example, the script SIR_model_script has two stages

that can be bundled into functions. The first stage runs the SIR model,

and it takes the following input parameters:

| Parameter | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

pop_size |

int |

Total number of susceptible people at the start of an outbreak |

beta |

float |

Average no. of new infections per infected person per day |

gamma |

float |

Inverse of the average number of days taken to recover |

days |

int |

Number of days to run the simulation for |

I_0 |

int |

Number of infected people at the start of the simulation |

The output data from this stage is:

| Parameter | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

S |

List[float] |

Number of susceptible people each day |

I |

List[float] |

Number of infected people each day |

R |

List[float] |

Number of recovered people each day |

We can therefore bundle this portion of the script into the function

SIR_model:

PYTHON

def SIR_model(pop_size, beta, gamma, days, I_0):

"""

Solves a SIR model numerically using a simple integration scheme.

Parameters

----------

pop_size: int

Total number of susceptible people at the start of an outbreak.

beta: float

Average number of new infections per infected person per day.

gamma: float

Inverse of the average number of days taken to recover.

days: int

Number of days to run the simulation for.

I_0: int

Number of infected people at the start of the simulation.

Returns

-------

S: List[float]

Number of susceptible people on each day.

I: List[float]

Number of infected people on each day.

R: List[float]

Number of recovered people on each day.

"""

# Initialise data

S = [] # Number of susceptible people each day

I = [] # Number of infected people each day

R = [] # Number of recovered people each day

S.append(pop_size - I_0)

I.append(I_0)

R.append(0)

# Solve model

for i in range(days):

# Get rate of change of S, I, and R

dS = - beta * S[i] * I[i] / pop_size

dR = gamma * I[i]

dI = -(dS + dR)

# Get values on next day

S.append(S[i] + dS)

I.append(I[i] + dI)

R.append(R[i] + dR)

return S, I, RNote that we’ve provided a nice docstring, so that users of our function can understand how to use it. The second stage of our script takes the results of the SIR model as input data, and produces a plot. We can therefore bundle the plotting parts of the script as follows:

PYTHON

# Note: imports should go at the top of the file

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def plot_SIR_model(S, I, R):

"""

Plot the results of a SIR simulation.

Parameters

----------

S: List[float]

Number of susceptible people on each day.

I: List[float]

Number of infected people on each day.

R: List[float]

Number of recovered people on each day.

Returns

-------

None

"""

plt.plot(range(len(S)), S, label="S")

plt.plot(range(len(I)), I, label="I")

plt.plot(range(len(R)), R, label="R")

plt.xlabel("Time /days")

plt.ylabel("Population")

plt.legend()

plt.show()If we save the two code blocks above to a file called

SIR_model.py, we can then open up a Python interpreter and

run the following:

PYTHON

>>> from SIR_model import SIR_model, plot_SIR_model

>>> S, I, R = SIR_model(

pop_size=8000000, beta=0.5, gamma=0.1, days=150, I_0=10

)

>>> plot_SIR_model(S, I, R)This should give us the same results as when we ran the script

earlier, and we can run the SIR_model function with

different inputs without needing to change the input parameters in the

file itself. The functions in our script are now therefore ‘reusable’,

and can be integrated in other workflows. The nice docstrings we added

can be viewed using the built-in help() function:

However, the script-like behaviour has been lost:

In the next section, we’ll show how to maintain script-like behaviour, and write reusable modules in the same file.

Maintaining Script-Like Functionality

If we wish, we can also maintain the script-like behaviour using the

if __name__ == "__main__".py idiom at the bottom of the

file SIR_model.py. Here, we create a special

if block at the bottom of our module, and within this we

call each of our functions in turn, using the outputs of one as inputs

to the next:

PYTHON

# file: SIR_model.py

# Add this after our function definitions

if __name__ == "__main__":

S, I, R = SIR_model(

pop_size=8000000, beta=0.5, gamma=0.1, days=150, I_0=10

)

plot_SIR_model(S, I, R)With this is place, we can still run the module as if it were a script:

However, this section will not run if we import the

file. Let’s break down how this works:

- Each Python module is automatically assigned a variable

__name__, and this is usually set to the name of the file without the.pyextension.

OUTPUT

"SIR_model"- The exception to the rule is when we run a Python module as a

script. In this case, the top-level file instead has its

__name__variable set to"__main__".

Therefore, the code written under

if __name__ == "__main__" will run if we use the module as

a script, but not if we import the file.

It prints "__main__"

It prints "name_test"

As we’ll see later, it can also be handy to bundle the contents of

our if __name__ == "__main__" block into a function, as

then we can import that function and access our script-like

behaviour in another way. This function can take any name, but is often

called main:

PYTHON

# file: SIR_model.py

def main():

S, I, R = SIR_model(

pop_size=8000000, beta=0.5, gamma=0.1, days=150, I_0=10

)

plot_SIR_model(S, I, R)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()We’ll use this format later when discussing ways to make runnable packages.

Managing PYTHONPATH

Our script is now import-able, so the

SIR_model function can be used from any other Python

script, module, or interpretter session. However, we still need to know

where the module is stored on our file system, which can make it

difficult to reuse the functions in a separate project. A simple

solution is to set the PYTHONPATH environment variable on

our system. On Linux machines, this can be achieved using:

If you want this to be set every time you open a terminal, you can

add the line to the file ~/.bashrc.

However, this is not recommended as a long-term solution, as a custom

PYTHONPATH can cause dependency conflicts between different

packages on our system and can be difficult to debug. In a later

chapter, we will show how to install our own modules using the

pip package manager, which gives us much more control over

how we integrate our modules into our Python environments (which may be

managed using tools such as venv or conda),

and also allows us to install packages from a remote repository. We’ll

also show how to upload our own packages to the remote repository PyPI,

and therefore allow others to download and install our code from the

command line!

Extra: Better Automation with Matplotlib

Earlier, we converted the plotting section of our script into a function that the user can call. There are two issues with the implementation as it stands:

- The use of

plt.show()interrupts the flow of the program and requires the user to manually save the figure or discard it. This makes it difficult to automate the production of figures. - As it calls

plt.plot()without first creating a new figure, it may interfere with our user’s Matplotlib code.

We can improve the function with a few changes:

- Rather than using Matplotlib’s ‘implicit’ API (such as by using

plt.plot()), which manages global Matplotlib objects, use the ‘explicit’ API, sometimes called the ‘object-oriented’ API. This requires handlingFigureandAxesobjects directly. - Optionally take in an

Axesobject. This way, the user can choose to set up their ownFigureandAxes, and our function can write to it. - Return the

Axesobject that we worked on, so that the user can make further changes if they wish. - Only use

plt.show()if the user requests it. Also provide an option to save the figure.

Here is an example of an improved function:

PYTHON

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def plot_SIR_model(S, I, R, ax=None, save_to=None, show=False):

"""

Plot the results of a SIR simulation.

Parameters

----------

S: List[float]

Number of susceptible people on each day.

I: List[float]

Number of infected people on each day.

R: List[float]

Number of recovered people on each day.

ax: Optional[plt.Axes], default None

Axes object on which to create the plot.

A new Axes is created if this is None.

save_to: Optional[str], default None

Name of the file to save the plot to.

Does not save if None.

show: bool, default False

If True, call plt.show() on completion.

Returns

-------

plt.Axes

The axes object the results have been plotted to.

"""

# Use plt.subplots to create Figure and Axes objects

# if one is not provided.

if ax is None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

# Create plot

ax.plot(range(len(S)), S, label="S")

ax.plot(range(len(I)), I, label="I")

ax.plot(range(len(R)), R, label="R")

ax.set_xlabel("Time /days")

ax.set_ylabel("Population")

ax.legend()

# Optionally save the figure

if save_to is not None:

fig = ax.get_figure()

fig.savefig(save_to)

# Optionally show the figure

if show:

plt.show()

return axThis gives our users much more control over how to create plots, and it allows our function to be used as part of a larger automated pipeline that runs without needing human input. There are many further ways we could improve this function and allow our users to finely control what’s plotted, such as by allowing the user to overwrite axis/line labels or interact with legend placement, but we’ll move on from this topic for now.

Extra: Better scripting with argparse

We showed earlier how to maintain script-like functionality in our modules. We’ll update that code to include our updated plotting function, so we’ll automatically save to a file if the user runs our script:

PYTHON

# file: SIR_model.py

def main():

S, I, R = SIR_model(

pop_size=8000000, beta=0.5, gamma=0.1, days=150, I_0=10

)

plot_SIR_model(S, I, R, save_to="SIR_model.png")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()An issue with our example is that it still requires the user to

manually edit the file if they wish to change the input or outputs. This

problem can be solved by instead taking arguments from the command line.

A simple interface can be created using sys.argv, which is

a list of command line arguments in the form of strings:

PYTHON

# file: SIR_model.py

import sys

def main():

# Note: sys.argv[0] is the name of our program!

pop_size = int(sys.argv[1])

beta = float(sys.argv[2])

gamma = float(sys.argv[3])

days = int(sys.argv[4])

I_0 = int(sys.argv[5])

output = sys.argv[6]

S, I, R = SIR_model(

pop_size=pop_size,

beta=beta,

gamma=gamma,

days=days,

I_0=I_0,

)

plot_SIR_model(S, I, R, save_to=output)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()However, this requires the user to provide every argument in order,

and doesn’t allow default arguments. We can achieve a better interface

using the built-in argparse library. The comments in the

code below explain how this works:

PYTHON

# file: SIR_model.py

from argparse import ArgumentParser

def main():

# Create an argument parser object. We can provide

# some info about our program here.

parser = ArgumentParser(

prog="SIR_model",

description="Solves SIR model and creates a plot",

)

# Add each argument to the parser. We can specify

# the types of each argument. Optional arguments

# should have single character names with a hypen,

# or longer names with a double dash.

parser.add_argument(

"-p", "--pop_size", type=int, default=10000000,

help="Total population size",

)

parser.add_argument(

"-b", "--beta", type=float, default=0.5,

help="Average no. of new infections per infected person per day",

)

parser.add_argument(

"-g", "--gamma", type=float, default=0.1,

help="Inverse of average number of days taken to recover",

)

parser.add_argument(

"-d", "--days", type=int, default=150,

help="Number of days to run the simulation",

)

parser.add_argument(

"-i", "--i0", type=int, default=10,

help="Number of infected people at the start of the simulation",

)

parser.add_argument(

"-o", "--output", default="SIR_model.png",

help="Output file to save plot to",

)

# Get each argument from the command line

args = parser.parse_args()

# Run our code

S, I, R = SIR_model(

pop_size=args.pop_size,

beta=args.beta,

gamma=args.gamma,

days=args.days,

I_0=args.i0,

)

plot_SIR_model(S, I, R, save_to=args.output)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()We can now run our script using inputs from the command line:

We defined each option with a default, so we don’t need to provide

all of them if we don’t want to. Each option has a long form with two

dashes (--output, --beta), and a short form

with one dash (-o, -b), which are

interchangeable (if we wish, we could provide only the short form or the

long form). Note that we can use either an equals = or a

space to separate the option name from its value.

If we had provided options without preceeding dashes, they would

become ‘positional’ arguments, and would be required. The order

positional arguments should be supplied is given by the order in which

they are added to the parser. For example, if we had added

beta and gamma as follows:

PYTHON

parser.add_argument(

"beta", type=float,

help="Average no. of new infections per infected person per day",

)

parser.add_argument(

"gamma", type=float,

help="Inverse of average number of days taken to recover",

)We would need to supply these arguments in order when running our code. Positional arguments are not specified by name on the command line:

If we forget how our script is supposed to be run,

argparse automatically provides a nice help message if we

run it with -h or --help:

usage: SIR_model [-h] [-p POP_SIZE] [-b BETA] [-g GAMMA] [-d DAYS] [-i I0] [-o OUTPUT]

Solves SIR model and creates a plot

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

-p POP_SIZE, --pop_size POP_SIZE

Total population size

-b BETA, --beta BETA Average no. of new infections per infected person per day

-g GAMMA, --gamma GAMMA

Inverse of average number of days taken to recover

-d DAYS, --days DAYS Number of days to run the simulation

-i I0, --i0 I0 Number of infected people at the start of the simulation

-o OUTPUT, --output OUTPUT

Output file to save plot toThere are many ways to control our command line interface in more

detail, such as constraining the possible user input choices, parsing

lists of inputs, and using ‘sub-parsers’ to split functionality across a

number of sub-commands, much like how pip handles its many

utilities:

Here, install and list are sub-commands,

which each handle a different set of their own args. We’ll show how to

achieve this in the next lesson, where we’ll expand our code from a

single module to a collection of modules known as a ‘package’.

Key Points

- Any Python file can be considered a ‘module’, and can be

import-ed. This just runs the code in the file, and makes the names of any objects in the module accessible using dot-notation. - If we bundle our Python scripts into a collection of functions, we can reuse those functions in other modules or in the Python interpretter.

- After turning our scripts into reusable modules, we can maintain

script-like behaviour using the idiom

if __name__ == "__main__". -

argparsecan be used to create sophisticated command line interfaces.