Moving Average Forecasts

Last updated on 2023-08-16 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 50 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can we analyze time-series data with trends?

Objectives

- Create a stationary time-series.

- Test for autocorrelation of time series values.

Introduction

In the previous section, we used baseline metrics to forecast one or more timesteps of a time-series dataset. These forecasts help demonstrate some of the characteristic features of time-series, but as we saw when we evaluated the results they may not make very accurate forecasts. There are some types of random time-series data for which using a baseline metric to forecast a single timestamp ahead is the only option. Since that doesn’t apply to the smart meter data - that is, power consumption values are not random - we will pass over that topic for now.

Instead, the smart meter data have characteristics that make them good candidates for methods that account for trends, autoregression, and one or more types of seasonality. We will develop these concepts over the next several lessons, beginning here with autocorrelation and the use of moving averages to make forecasts using autocorrelated data.

About the code

The code used in this lesson is based on and, in some cases, a direct application of code used in the Manning Publications title, Time series forecasting in Python, by Marco Peixeiro.

Peixeiro, Marco. Time Series Forecasting in Python. [First edition]. Manning Publications Co., 2022.

The original code from the book is made available under an Apache 2.0 license. Use and application of the code in these materials is within the license terms, although this lesson itself is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 license. Any further use or adaptation of these materials should cite the source code developed by Peixeiro:

Peixeiro, Marco. Timeseries Forecasting in Python [Software code]. 2022. Accessed from https://github.com/marcopeix/TimeSeriesForecastingInPython.

Create a subset to demonstrate autocorrelation

As we did in the previous episode, rather than read a dataset that is ready for analysis we are going to read one of the smart meter datasets and create a subset that demonstrates the characteristics of interest for this section of the lesson.

First we will import the necessary libraries. Note that in additional

to Pandas, Numpy, and Matplotlib we are also importing modules from

statsmodels and sklearn. These are Python

libraries that come with many methods for modeling and machine

learning.

PYTHON

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from statsmodels.tsa.stattools import adfuller

from statsmodels.graphics.tsaplots import plot_acf

from statsmodels.tsa.statespace.sarimax import SARIMAX

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

from sklearn.metrics import mean_absolute_errorRead the data. In this case we are using just a single smart meter.

OUTPUT

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 105012 entries, 0 to 105011

Data columns (total 5 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 INTERVAL_TIME 105012 non-null object

1 METER_FID 105012 non-null int64

2 START_READ 105012 non-null float64

3 END_READ 105012 non-null float64

4 INTERVAL_READ 105012 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(3), int64(1), object(1)

memory usage: 4.0+ MB

NoneSet the datetime index and resample to a daily frequency.

PYTHON

df.set_index(pd.to_datetime(df["INTERVAL_TIME"]), inplace=True)

df.sort_index(inplace=True)

print(df.info())OUTPUT

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

DatetimeIndex: 105012 entries, 2017-01-01 00:00:00 to 2019-12-31 23:45:00

Data columns (total 5 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 INTERVAL_TIME 105012 non-null object

1 METER_FID 105012 non-null int64

2 START_READ 105012 non-null float64

3 END_READ 105012 non-null float64

4 INTERVAL_READ 105012 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(3), int64(1), object(1)

memory usage: 4.8+ MB

NoneOUTPUT

INTERVAL_READ

INTERVAL_TIME

2017-01-01 11.7546

2017-01-02 15.0690

2017-01-03 11.6406

2017-01-04 22.0788

2017-01-05 12.8070Subset to January - July, 2019 and plot the data.

PYTHON

jan_july_2019 = daily_data.loc["2019-01": "2019-07"].copy()

jan_july_2019["INTERVAL_READ"].plot()

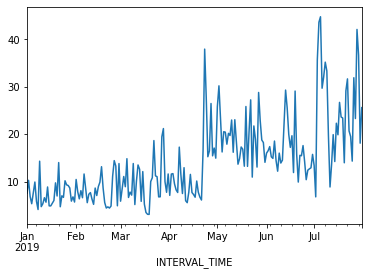

The above plot demonstrates a gradual trend towards increased power consumption through late spring and into summer. This is expected - power consumption in US households tends to increase as the weather becomes warmer and people begin to use air conditioners or evaporative coolers.

Differencing and autocorrelation

In order to make a forecast using the moving average model, however,

the data need to be stationary. That is, we need to remove trends from

the data. We can test for stationarity using the adfuller

function from statsmodels.

PYTHON

adfuller_test = adfuller(jan_july_2019["INTERVAL_READ"])

print(f'ADFuller result: {adfuller_test[0]}')

print(f'p-value: {adfuller_test[1]}')OUTPUT

ADFuller result: -2.533089941397639

p-value: 0.10762933815081588The p-value above is greater than 0.05, which in this case indicates that the data are not stationary. That is, there is a trend in the data.

We also want to test for autocorrelation.

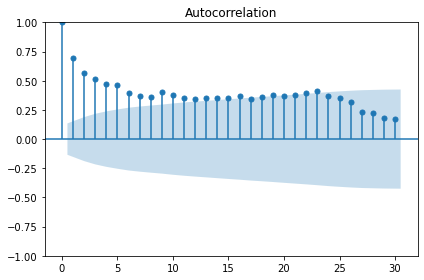

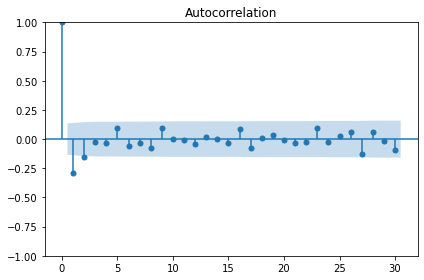

The plot above shows significant autocorrelation up to the 16th lag. Before we can make forecasts on the data, we need to make the data stationary by removing the trend using a technique called differencing. Differencing also reduces the amount of autocorrelation in the data.

Differencing data this way creates a Numpy array of values that represent the difference between one INTERVAL_READ value and the next. We can see this by comparing the head of the jan_july_2019 dataframe with the first five differenced values.

PYTHON

jan_july_2019_differenced = np.diff(jan_july_2019["INTERVAL_READ"], n=1)

print("Head of dataframe:", jan_july_2019.head())

print("\nDifferenced values:", jan_july_2019_differenced[:5])OUTPUT

Head of dataframe: INTERVAL_READ

INTERVAL_TIME

2019-01-01 7.5324

2019-01-02 10.2534

2019-01-03 6.8544

2019-01-04 5.3250

2019-01-05 7.5480

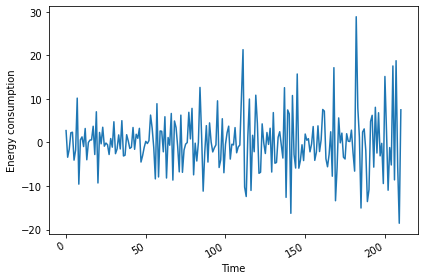

Differenced values: [ 2.721 -3.399 -1.5294 2.223 2.3466]Plotting the result shows that there are no obvious trends in the differenced data.

PYTHON

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(jan_july_2019_differenced)

ax.set_xlabel('Time')

ax.set_ylabel('Energy consumption')

fig.autofmt_xdate()

plt.tight_layout()

Evaluating the AD Fuller test on the difference data indicates that the data are stationary.

PYTHON

adfuller_test = adfuller(jan_july_2019_differenced)

print(f'ADFuller result: {adfuller_test[0]}')

print(f'p-value: {adfuller_test[1]}')OUTPUT

ADFuller result: -7.966077912452976

p-value: 2.8626643210939594e-12The autocorrelation plot still shows some significant autocorrelation up to lag 2. We will use this information to supply the order parameter for the moving average model, below.

Moving average forecast

For our training data, we will use the 90% of the dataset. The remaining 10% of the data will be used to evaluate the performance of the moving average forecast in comparison with a baseline forecast.

Since the differenced data is a numpy array, we also need to convert it to a dataframe.

PYTHON

jan_july_2019_differenced = pd.DataFrame(jan_july_2019_differenced,

columns=["INTERVAL_READ"])

train = jan_july_2019_differenced[:int(round(len(jan_july_2019_differenced) * .9, 0))] # ~90% of data

test = jan_july_2019_differenced[int(round(len(jan_july_2019_differenced) * .9, 0)):] # ~10% of data

print("Training data length:", len(train))

print("Test data length:", len(test))OUTPUT

Training data length: 190

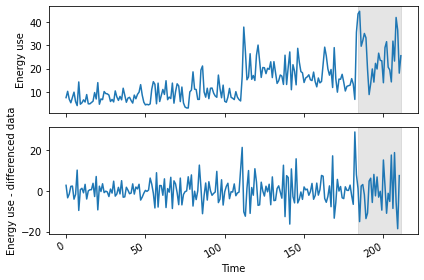

Test data length: 21We can plot the original and differenced data together. The shaded area is the date range for which we will be making and evaluating forecasts.

PYTHON

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(nrows=2, ncols=1, sharex=True)

ax1.plot(jan_july_2019["INTERVAL_READ"].values)

ax1.set_xlabel('Time')

ax1.set_ylabel('Energy use')

ax1.axvspan(184, 211, color='#808080', alpha=0.2)

ax2.plot(jan_july_2019_differenced["INTERVAL_READ"])

ax2.set_xlabel('Time')

ax2.set_ylabel('Energy use - differenced data')

ax2.axvspan(184, 211, color='#808080', alpha=0.2)

fig.autofmt_xdate()

plt.tight_layout()

We are going to evaluate the performance of the moving average forecast against a baseline forecast based on the last known value. Since we will be using and building on these methods throughout this lesson, we will create functions for each forecast.

The last_known() function is a more flexible version of

the process used in the previous episode to calculate a baseline

forecast. In that case we used single value - the last known meter

reading from the training dataset - and applied it as a forecast to the

entire test set. In our updated function, we are passing

horizon and window arguments that allow us to pull

values from a moving frame of reference within the differenced data.

The moving_average() function is an implementation of

the seasonal auto-regressive moving average model that is

included in the statsmodels library.

PYTHON

def last_known(data, training_len, horizon, window):

total_len = training_len + horizon

pred_last_known = []

for i in range(training_len, total_len, window):

subset = data[:i]

last_known = subset.iloc[-1].values[0]

pred_last_known.extend(last_known for v in range(window))

return pred_last_known

def moving_average(data, training_len, horizon, ma_order, window):

total_len = training_len + horizon

pred_MA = []

for i in range(training_len, total_len, window):

model = SARIMAX(data[:i], order=(0,0, ma_order))

res = model.fit(disp=False)

predictions = res.get_prediction(0, i + window - 1)

oos_pred = predictions.predicted_mean.iloc[-window:]

pred_MA.extend(oos_pred)

return pred_MABoth functions take the differenced dataframe as input and return a list of predicted values that is equal to the length of the test dataset.

PYTHON

pred_df = test.copy()

TRAIN_LEN = len(train)

HORIZON = len(test)

ORDER = 2

WINDOW = 2

pred_last_value = last_known(jan_july_2019_differenced, TRAIN_LEN, HORIZON, WINDOW)

pred_MA = moving_average(jan_july_2019_differenced, TRAIN_LEN, HORIZON, ORDER, WINDOW)

pred_df['pred_last_value'] = pred_last_value

pred_df['pred_MA'] = pred_MA

print(pred_df.head())OUTPUT

INTERVAL_READ pred_last_value pred_MA

189 -13.5792 -1.863 -1.870535

190 -10.8660 -1.863 -0.379950

191 4.8054 -10.866 9.760944

192 6.2280 -10.866 4.751856

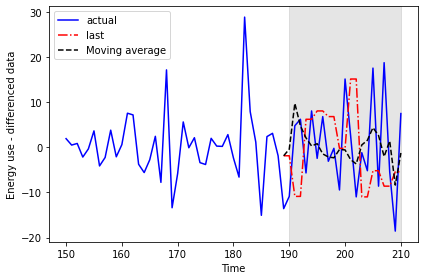

193 -5.6718 6.228 2.106354Plotting the data allows for a visual comparison of the forecasts.

PYTHON

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(jan_july_2019_differenced[150:]['INTERVAL_READ'], 'b-', label='actual')

ax.plot(pred_df['pred_last_value'], 'r-.', label='last')

ax.plot(pred_df['pred_MA'], 'k--', label='Moving average')

ax.axvspan(190, 210, color='#808080', alpha=0.2)

ax.legend(loc=2)

ax.set_xlabel('Time')

ax.set_ylabel('Energy use - differenced data')

plt.tight_layout()

This time we will use the mean_squared_error function

from the sklearn library to evaluate the results.

PYTHON

mse_last = mean_squared_error(pred_df['INTERVAL_READ'], pred_df['pred_last_value'])

mse_MA = mean_squared_error(pred_df['INTERVAL_READ'], pred_df['pred_MA'])

print("Last known forecast, mean squared error:", mse_last)

print("Moving average forecast, mean squared error:", mse_MA)OUTPUT

Last known forecast, mean squared error: 185.5349359527273

Moving average forecast, mean squared error: 86.16289030738947We can see that the moving average forecast performs much better than the last known value baseline forecast.

Transform the forecast to original scale

Because we differenced our data above in order to apply a moving

average forecast, we now need to transform the data back to its original

scale. To do this, we apply the numpy cumsum() method to

calculate the cumulative sums of the values in the differenced dataset.

We then map these sums to their corresponding rows of the original

data.

The transformed data are only being applied to the rows of the source

data that were used for the test dataset, so we can use the

tail() function to inspect the result.

PYTHON

jan_july_2019['pred_usage'] = pd.Series()

jan_july_2019['pred_usage'][190:] = jan_july_2019['INTERVAL_READ'].iloc[190] + pred_df['pred_MA'].cumsum()

print(jan_july_2019.tail())OUTPUT

INTERVAL_READ pred_usage

INTERVAL_TIME

2019-07-27 23.2752 31.008305

2019-07-28 42.0504 28.974839

2019-07-29 36.6444 30.387655

2019-07-30 18.0828 22.025803

2019-07-31 25.5774 20.781842We can plot the result to compare the transformed forecasts against the actual daily power consumption.

PYTHON

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(jan_july_2019['INTERVAL_READ'].values, 'b-', label='actual')

ax.plot(jan_july_2019['pred_usage'].values, 'k--', label='MA(2)')

ax.legend(loc=2)

ax.set_xlabel('Time')

ax.set_ylabel('Energy consumption')

ax.axvspan(191, 210, color='#808080', alpha=0.2)

ax.set_xlim(170, 210)

fig.autofmt_xdate()

plt.tight_layout()

Finally, to evaluate the performance of the moving average forecast

against the actual values in the undifferenced data, we use the

mean_absolute_error from the sklearn

library.

PYTHON

mae_MA_undiff = mean_absolute_error(jan_july_2019['INTERVAL_READ'].iloc[191:],

jan_july_2019['pred_usage'].iloc[191:])

print("Mean absolute error of moving average forecast", mae_MA_undiff)OUTPUT

Mean absolute error of moving average forecast 8.457690692889582Key Points

- Use differencing to make time-series stationary.

-

statsmodelsis a Python library with time-series methods built in.