OOD detection: overview

Last updated on 2024-12-19 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What are out-of-distribution (OOD) data, and why is detecting them important in machine learning models?

- What are threshold-based methods, and how do they help detect OOD data?

Objectives

- Understand the concept of out-of-distribution data and its implications for machine learning models.

- Learn the principles behind threshold-based OOD detection methods.

What is out-of-distribution (OOD) data

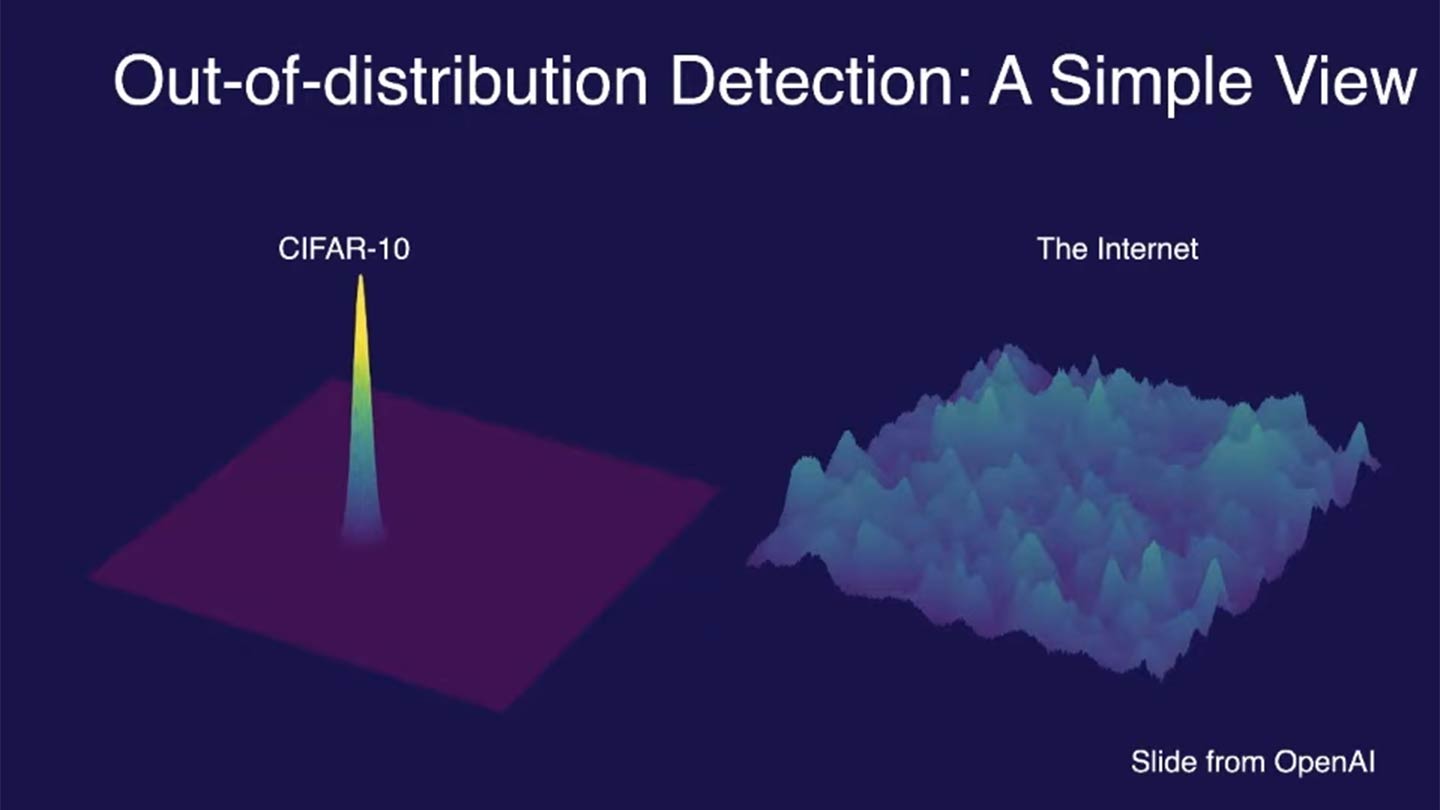

Out-of-distribution (OOD) data refers to data that significantly differs from the training data on which a machine learning model was built, i.e., the in-distribution (ID). For example, the image below compares the training data distribution of CIFAR-10, a popular dataset used for image classification, with the vastly broader and more diverse distribution of images found on the internet:

CIFAR-10 contains 60,000 images across 10 distinct classes (e.g., airplanes, dogs, trucks), with carefully curated examples for each class. However, the internet features an essentially infinite variety of images, many of which fall outside these predefined classes or include unseen variations (e.g., new breeds of dogs or novel vehicle designs). This contrast highlights the challenges models face when they encounter data that significantly differs from their training distribution.

How OOD data manifests in ML pipelines

The difference between in-distribution (ID) and OOD data can arise from:

- Semantic shift: The OOD sample belongs to a class that was not present during training (classification). With continuous prediction/regression, semantic shift occurs when the underlying relationship between X and Y changes.

- Covariate shift: The OOD sample comes from a domain where the input feature distribution is drastically different from the training data. The input feature distribution changes, but the underlying relationship between X and Y stays the same.

Semantic shift often co-occurs with covariate shift.

Distinguishing semantic shift vs. covariate shift

You trained a model using the CIFAR-10 dataset to classify images into 10 classes (e.g., airplanes, dogs, trucks). Now, you deploy the model to classify images found on the internet. Consider the following scenarios and classify each as Semantic Shift, Covariate Shift, or Both. Provide reasoning for your choice.

Scenario A: The internet dataset contains images of drones, which were not present in the CIFAR-10 dataset. The model struggles to classify them.

Scenario B: The internet dataset has dog images, but these dogs are primarily captured in outdoor settings with unfamiliar backgrounds and lighting conditions compared to the training data.

Scenario C: The internet dataset contains images of hybrid animals (e.g., “wolf-dogs”) that do not belong to any CIFAR-10 class. The model predicts incorrectly.

Scenario D: The internet dataset includes high-resolution images of airplanes, while the CIFAR-10 dataset contains only low-resolution airplane images. The model performs poorly on these new airplane images.

Scenario E: A researcher retrains the CIFAR-10 model using an updated dataset where labels for “trucks” are now redefined to include pickup trucks, which were previously excluded. The new labels confuse the original model.

-

Scenario A: Semantic Shift

- Drones represent a new class not seen during training, so the model encounters a semantic shift.

-

Scenario B: Covariate Shift

- The distribution of input features (e.g., lighting, background) changes, but the semantic relationship (e.g., dogs are still dogs) remains intact.

-

Scenario C: Both

- Hybrid animals represent a semantic shift (new class), and unfamiliar feature distributions (e.g., traits of wolves and dogs combined) also introduce covariate shift.

-

Scenario D: Covariate Shift

- The resolution of the images (input features) changes, but the semantic class of airplanes remains consistent.

-

Scenario E: Semantic Shift

- The relationship between input features and class labels has changed, as the definition of the “truck” class has been altered.

Why does OOD data matter?

Models trained on a specific distribution might make incorrect predictions on OOD data, leading to unreliable outputs. In critical applications (e.g., healthcare, autonomous driving), encountering OOD data without proper handling can have severe consequences.

Ex1: Tesla crashes into jet

In April 2022, a Tesla Model Y crashed into a $3.5 million private jet at an aviation trade show in Spokane, Washington, while operating on the “Smart Summon” feature. The feature allows Tesla vehicles to “autonomously” navigate parking lots to their owners, but in this case, it resulted in a significant mishap. The car continued to move forward even after making contact with the jet, pushing the expensive aircraft and causing notable damage.

The crash highlighted several issues with Tesla’s Smart Summon feature, particularly its object detection capabilities. The system failed to recognize and appropriately react to the presence of the jet, a problem that has been observed in other scenarios where the car’s sensors struggle with objects that are lifted off the ground or have unusual shapes.

Ex2: IBM Watson for Oncology

Around a decade ago, the excitement surrounding AI in healthcare often exceeded its actual capabilities. In 2016, IBM launched Watson for Oncology, an AI-powered platform for treatment recommendations, to much public enthusiasm. However, it soon became apparent that the system was both costly and unreliable, frequently generating flawed advice while operating as an opaque “black box”. IBM Watson for Oncology faced several issues due to OOD data. The system was primarily trained on data from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), which did not generalize well to other healthcare settings. This led to:

- Unsafe recommendations: Watson for Oncology provided treatment recommendations that were not safe or aligned with standard care guidelines in many cases outside of MSK. This happened because the training data was not representative of the diverse medical practices and patient populations in different regions

- Bias in training data: The system’s recommendations were biased towards the practices at MSK, failing to account for different treatment protocols and patient needs elsewhere. This bias is a classic example of an OOD issue, where the model encounters data (patients and treatments) during deployment that significantly differ from its training data

By 2022, IBM had taken Watson for Oncology offline, marking the end of its commercial use.

Ex3: Doctors using GPT3

Misdiagnosis and inaccurate medical advice

In various studies and real-world applications, GPT-3 has been shown to generate inaccurate medical advice when faced with OOD data. This can be attributed to the fact that the training data, while extensive, does not cover all possible medical scenarios and nuances, leading to hallucinations or incorrect responses when encountering unfamiliar input.

A study published by researchers at Stanford found that GPT-3, even when using retrieval-augmented generation, provided unsupported medical advice in about 30% of its statements. For example, it suggested the use of a specific dosage for a defibrillator based on monophasic technology, while the cited source only discussed biphasic technology, which operates differently.

Fake medical literature references

Another critical OOD issue is the generation of fake or non-existent medical references by LLMs. When LLMs are prompted to provide citations for their responses, they sometimes generate references that sound plausible but do not actually exist. This can be particularly problematic in academic and medical contexts where accurate sourcing is crucial.

In evaluations of GPT-3’s ability to generate medical literature references , it was found that a significant portion of the references were either entirely fabricated or did not support the claims being made. This was especially true for complex medical inquiries that the model had not seen in its training data.

Recognizing OOD data in your work

Think of a scenario from your field of work or study where encountering out-of-distribution (OOD) data would be problematic. Consider the following:

- What would be the in-distribution (ID) data in that context?

- What might constitute OOD data, and how could it impact the results or outputs of your system/model?

Share your example with the group. Discuss any strategies currently used or that could be used to mitigate the challenges posed by OOD data in your example.

Detecting and handling OOD data

Given the problems posed by OOD data, a reliable model should identify such instances, and then:

- Reject them during inference

- Ideally, hand these OOD instances to a model trained on a more similar distribution (an in-distribution).

The second step is much more complicated/involved since it requires matching OOD data to essentially an infinite number of possible classes. For the current scope of this workshop, we will focus on just the first step.

Threshold-based

How can we ensure our models do not perform poorly in the presence of OOD data? Over the past several years, there have been a wide assortment of new methods developed to tackle this task. The central idea behind all of these methods is to define a threshold on a certain score or confidence measure, beyond which the data point is considered out-of-distribution. Typically, these scores are derived from the model’s output probabilities, logits (pre-softmax outputs), or other statistical measures of uncertainty. There are two general classes of threshold-based OOD detection methods: output-based and distance-based.

1) Output-based thresholds

Output-based Out-of-Distribution (OOD) detection refers to methods that determine whether a given input is out-of-distribution based on the output of a trained model. The main approaches within output-based OOD detection include:

- Softmax scores: The softmax output of a neural network represents the predicted probabilities for each class. A common threshold-based method involves setting a confidence threshold, and if the maximum softmax score of an instance falls below this threshold, it is flagged as OOD.

- Energy: The energy-based method also uses the network’s output but measures the uncertainty in a more nuanced way by calculating an energy score. The energy score typically captures the confidence more robustly, especially in high-dimensional spaces, and can be considered a more general and reliable approach than just using softmax probabilities.

2) Distance-based thresholds

Distance-based methods calculate the distance of an instance from the distribution of training data features learned by the model. If the distance is beyond a certain threshold, the instance is considered OOD. Common distance-based approaches include:

- Mahalanobis distance: This method calculates the Mahalanobis distance of a data point from the mean of the training data distribution. A high Mahalanobis distance indicates that the instance is likely OOD.

- K-nearest neighbors (KNN): This method involves computing the distance to the k-nearest neighbors in the training data. If the average distance to these neighbors is high, the instance is considered OOD.

We will focus on output-based methods (softmax and energy) in the next episode and then do a deep dive into distance-based methods in a later next episode.

- Out-of-distribution (OOD) data significantly differs from training data and can lead to unreliable model predictions.

- Threshold-based methods use model outputs or distances in feature space to detect OOD instances by defining a score threshold.