Content from Overview of Amazon SageMaker

Last updated on 2025-11-07 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 10 minutes

Overview

Questions

- Why use SageMaker for machine learning?

Objectives

- Introduce SageMaker

Amazon SageMaker is a comprehensive machine learning (ML) platform that empowers users to build, train, tune, and deploy models at scale. Designed to streamline the ML workflow, SageMaker supports data scientists and researchers in tackling complex machine learning problems without needing to manage underlying infrastructure. This allows you to focus on developing and refining your models while leveraging AWS’s robust computing resources for efficient training and deployment.

Why use SageMaker for machine learning?

SageMaker provides several features that make it an ideal choice for researchers and ML practitioners:

High-performance compute only when needed: SageMaker lets you develop interactively in lightweight, inexpensive notebook environments (or your own laptop) and then launch training, tuning, or inference jobs on more powerful instance types only when necessary. This approach keeps costs low during development and ensures you only pay for expensive compute when you’re actively using it.

Support for custom scripts: Most training and inference scripts can be run using pre-configured estimators or containers that come with popular ML frameworks such as scikit-learn, PyTorch, TensorFlow, and Hugging Face already installed. In many cases, you can simply include a

requirements.txtfile to add any additional dependencies you need. When you need more control, SageMaker also supports fully custom Docker containers, so you can bring your own code, dependencies, and environments for training, tuning, and inference — all deployed on scalable AWS infrastructure.-

Flexible compute options: SageMaker lets you easily select instance types tailored to your project needs. For exploratory analysis, use a lightweight CPU (e.g., ml.m5.large). For compute-intensive tasks, such as training deep learning models, you can switch to GPU instances for faster processing. We’ll cover instances more in-depth throughout the lesson (and how to select them), but here’s a preview of the the different types:

- CPU instances (e.g., ml.m5.large — $0.12/hour): Suitable for general ML workloads, feature engineering, and inference tasks.

- Memory-optimized instances (e.g., ml.r5.2xlarge — $0.65/hour): Best for handling large datasets in memory.

- GPU instances (e.g., ml.p3.2xlarge — $3.83/hour): Optimized for compute-intensive tasks like deep learning training, offering accelerated processing.

- For more details, check out the supplemental “Instances for ML” page. We’ll discuss this topic more throughout the lesson.

Parallelized training and tuning: SageMaker enables parallelized training across multiple instances, reducing training time for large datasets and complex models. It also supports parallelized hyperparameter tuning, allowing efficient exploration of model configurations with minimal code while maintaining fine-grained control over the process.

Ease of orchestration / Simplified ML pipelines: Traditional high-performance computing (HPC) or high-throughput computing (HTC) environments often require researchers to break ML workflows into separate batch jobs, manually orchestrating each step (e.g., submitting preprocessing, training, cross-validation, and evaluation as distinct tasks and stitching the results together later). This can be time-consuming and cumbersome, as it requires converting standard ML code into complex Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) and job dependencies. By eliminating the need to manually coordinate compute jobs, SageMaker dramatically reduces ML pipeline complexity, making it easier for researchers to quickly develop and iterate on models efficiently.

Cost management and monitoring: SageMaker includes built-in monitoring tools to help you track and manage costs, ensuring you can scale up efficiently without unnecessary expenses. For many common use cases of ML/AI, SageMaker can be very affordable. For example, training roughly 100 small to medium-sized models (e.g., logistic regression, random forests, or lightweight deep learning models with a few million parameters) on a small dataset (under 10GB) can cost under $20, making it accessible for many research projects.

In summary, Amazon SageMaker is a fully managed machine learning platform that simplifies building, training, tuning, and deploying models at scale. Unlike traditional research computing environments, which often require manual job orchestration and complex dependency management, SageMaker provides an integrated and automated workflow, allowing users to focus on model development rather than infrastructure. With support for on-demand compute resources, parallelized training and hyperparameter tuning, and flexible model deployment options, SageMaker enables researchers to scale experiments efficiently. Built-in cost tracking and monitoring tools also help keep expenses manageable, making SageMaker a practical choice for both small-scale research projects and large-scale ML pipelines. By combining preconfigured machine learning algorithms, support for custom scripts, and robust computing power, SageMaker reduces the complexity of ML development, empowering researchers to iterate faster and bring models to production more seamlessly.

- SageMaker simplifies ML workflows by eliminating the need for manual job orchestration.

- Flexible compute options allow users to choose CPU, GPU, or memory-optimized instances based on workload needs.

- Parallelized training and hyperparameter tuning accelerate model development.

- SageMaker supports both built-in ML algorithms and custom scripts via Docker containers.

- Cost monitoring tools help track and optimize spending on AWS resources.

- SageMaker streamlines scaling from experimentation to deployment, making it suitable for both research and production.

Content from Data Storage: Setting up S3

Last updated on 2025-12-19 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I store and manage data effectively in AWS for SageMaker workflows?

- What are the best practices for using S3 versus EC2 storage for machine learning projects?

Objectives

- Explain data storage options in AWS for machine learning projects.

- Describe the advantages of S3 for large datasets and multi-user workflows.

- Outline steps to set up an S3 bucket and manage data within SageMaker.

Storing data on AWS

Machine learning and AI projects rely on data, making efficient storage and management essential. AWS provides several options for storing data, each with different use cases and trade-offs.

Consult your institution’s IT before handling sensitive data in AWS

When using AWS for research, ensure that no restricted or sensitive data is uploaded to S3 or any other AWS service unless explicitly approved by your institution’s IT or cloud security team. For projects involving sensitive or regulated data (e.g., HIPAA, FERPA, or proprietary research data), consult your institution’s cloud security or compliance team to explore approved solutions. This may include encryption, restricted-access storage, or dedicated secure environments. If unsure about data classification, review your institution’s data security policies before uploading.

Options for storage: EC2 Instance or S3

When working with SageMaker and other AWS services, you have options for data storage, primarily EC2 instances or S3.

What is an EC2 instance?

An Amazon EC2 (Elastic Compute Cloud) instance is a virtual server environment where you can run applications, process data, and store data temporarily. EC2 instances come in various types and sizes to meet different computing and memory needs, making them versatile for tasks ranging from light web servers to intensive machine learning workloads. For example, when you launch a new Jupyter notebook from Sagemaker, this notebook is run on an an EC2 instance configured to run Jupyter notebooks, enabling direct data processing.

When to store data directly on EC2

Using an EC2 instance for data storage can be useful for temporary or small datasets, especially during processing within a Jupyter notebook. However, this storage is not persistent; if the instance is stopped or terminated, the data is erased. Therefore, EC2 is ideal for one-off experiments or intermediate steps in data processing.

Limitations of EC2 storage

- Scalability: EC2 storage is limited to the instance’s disk capacity, so it may not be ideal for very large datasets.

- Cost: EC2 storage can be more costly for long-term use compared to S3.

- Data Persistence: EC2 data may be lost if the instance is stopped or terminated, unless using Elastic Block Store (EBS) for persistent storage.

What is an S3 bucket?

Storing data in an S3 bucket is generally preferred

for machine learning workflows on AWS, especially when using SageMaker.

An S3 bucket is a container in Amazon S3 (Simple Storage Service) where

you can store, organize, and manage data files. Buckets act as the

top-level directory within S3 and can hold a virtually unlimited number

of files and folders, making them ideal for storing large datasets,

backups, logs, or any files needed for your project. You access objects

in a bucket via a unique S3 URI (e.g.,

s3://your-bucket-name/your-file.csv), which you can use to

reference data across various AWS services like EC2 and SageMaker.

Benefits of using S3 (recommended for SageMaker and ML workflows)

For flexibility, scalability, and cost efficiency, store data in S3 and load it into EC2 as needed. This setup allows:

- Separation of storage and compute: The most essential advantage. Data in S3 remains accessible even when EC2 instances are stopped or terminated, reducing costs and improving workflow flexibility.

-

Easy data sharing: Datasets in S3 are easier to

share with team members or across projects compared to EC2

storage.

-

Integration with AWS services: SageMaker, Lambda,

and other AWS services can read directly from and write back to S3,

streamlining ML workflows.

-

Scalability: S3 handles large datasets efficiently,

enabling storage beyond the limits of an EC2 instance’s disk

space.

-

Cost efficiency: S3 storage is generally lower cost

than expanding EC2 disk volumes, and you only pay for the storage you

use.

- Data persistence: Unlike EC2 storage, which can be lost if an instance is terminated, S3 ensures long-term data availability.

Recommended approach: S3 buckets

In order to upload our titanic dataset to an S3 bucket on AWS, we’ll follow the below summary procedure (details follow):

- Log in to AWS Console and navigate to S3.

- Create a new bucket or use an existing one.

- Upload your dataset files.

- Use the object URL to reference your data in future experiments.

Detailed procedure

2. Navigate to S3

- Type “S3” in the search bar

- Recommended: Select the star icon to save S3 as a bookmark in your AWS toolbar

- Select S3 - Scalable Storage in the Cloud

3. Create a new bucket

- Click Create Bucket and enter a unique name, and

note that bucket name must not contain uppercase characters. To easily

find this bucket later in our shared AWS account, please use the

following naming convention:

teamname-yourname-dataname(e.g., sinkorswim-doejohn-titanic). -

Access Control (ACLs): Disable ACLs (recommended).

-

What are ACLs? Access Control Lists (ACLs) define

fine-grained permissions at the object level, allowing you to grant

specific users or AWS accounts access to individual files in your

bucket.

- Why disable them? AWS now recommends managing access through bucket policies and IAM roles, which offer better security and are easier to manage at scale. Unless you have a specific need for ACLs, disabling them is the best practice.

-

What are ACLs? Access Control Lists (ACLs) define

fine-grained permissions at the object level, allowing you to grant

specific users or AWS accounts access to individual files in your

bucket.

- Public Access: Turn on “Block all public access” (recommended). This setting prevents unauthorized access and accidental data exposure. If you need external access, use IAM policies or signed URLs instead.

-

Versioning: Disable unless you need multiple

versions of objects (unnecessary for ML Marathon). Enable only if

needed, as versioning increases storage costs. Useful when tracking

changes to datasets over time but unnecessary for static datasets.

-

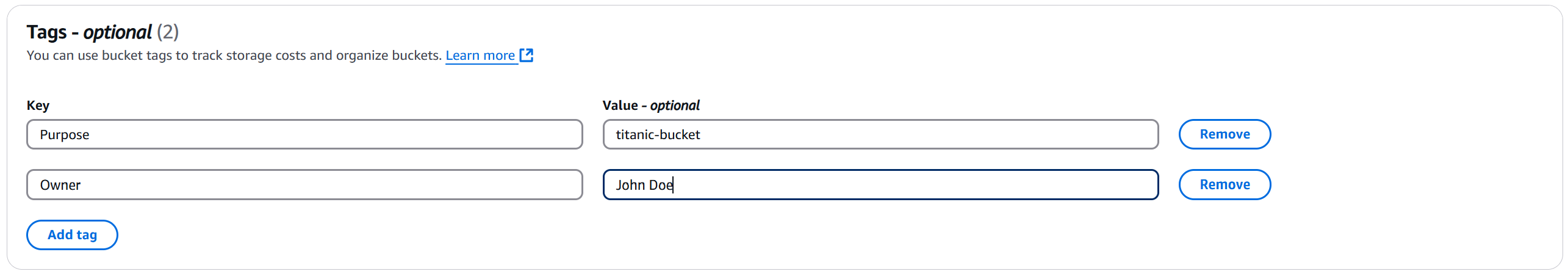

Tags: Adding tags to your S3 buckets is a great way

to track project-specific costs and usage over time, especially as data

and resources scale up. To easily track costs associated with your

bucket in our shared AWS account, add the following fields:

- Project: teamname (if participating in ML Marathon)

-

Name: yourname

- Purpose: Bucket-titanic

- Click Create Bucket at the bottom once everything above has been configured

4. Edit bucket policy

Once the bucket is created, you’ll be brought to a page that shows all of your current buckets (and those on our shared account). We’ll have to edit our bucket’s policy to allow ourselves proper access to any files stored there (e.g., read from bucket, write to bucket). To set these permissions…

- Click on the name of your bucket to bring up additional options and settings.

- Click the Permissions tab

- Scroll down to Bucket policy and click Edit. Paste the following policy, editing the bucket name “sinkorswim-doejohn-titanic” to reflect your bucket’s name

JSON

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": {

"AWS": [

"arn:aws:iam::183295408236:role/ml-sagemaker-use",

"arn:aws:iam::183295408236:role/ml-sagemaker-bedrock-use"

]

},

"Action": [

"s3:GetObject",

"s3:PutObject",

"s3:DeleteObject",

"s3:ListMultipartUploadParts"

],

"Resource": [

"arn:aws:s3:::sinkorswim-chrisendemann-titanic",

"arn:aws:s3:::sinkorswim-chrisendemann-titanic/*"

]

}

]

}For workshop attendees, this policy grants the

ml-sagemaker-use IAM role access to specific S3 bucket

actions, ensuring they can use the bucket for reading, writing,

deleting, and listing parts during multipart uploads. Attendees should

apply this policy to their buckets to enable SageMaker to operate on

stored data.

General guidance for setting up permissions outside of this workshop

When setting up a bucket outside of this workshop, it’s essential to

create a similar IAM role (such as ml-sagemaker-use) with

policies that provide controlled access to S3 resources, ensuring only

the necessary actions are permitted for security and

cost-efficiency.

Create an IAM role: Set up an IAM role for SageMaker to assume, with necessary S3 access permissions, such as

s3:GetObject,s3:PutObject,s3:DeleteObject, ands3:ListMultipartUploadParts, as shown in the policy above.Attach permissions to S3 buckets: Attach bucket policies that specify this role as the principal, as in our bucket policy above

More information: For a detailed guide on setting up roles and policies for SageMaker, refer to the AWS SageMaker documentation on IAM roles and policies. This resource explains role creation, permission setups, and policy best practices tailored for SageMaker’s operations with S3 and other AWS services.

This setup ensures that your SageMaker operations will have the access needed without exposing the bucket to unnecessary permissions or external accounts.

5. Upload files to the bucket

- If you haven’t downloaded these files yet (part of workshop setup),

download the data for this workshop: data.zip

- Extract the zip folder contents (Right-click -> Extract all on Windows; Double-click on mac)

- Save the two data files (train and test) to a location where they

can easily be accessed. E.g., …

~/Downloads/data/titanic_train.csv~/Downloads/data/titanic_test.csv

- Navigate to the Objects tab of your bucket, then Upload.

-

Add Files (

titanic_train.csv,titanic_test.csv) and click Upload to complete.

6. Take note of S3 URI for your data

- After uploading a file to S3, click on the file to locate its Object URI (e.g., s3://doejohn-titanic-s3/titanic_train.csv). The Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) is a unique address that specifies the location of the file within S3. This URI is essential for referencing data in AWS services like SageMaker, where it will be used to load data for processing and model training.

S3 bucket costs

S3 bucket storage incurs costs based on data storage, data transfer, and request counts.

Storage costs

- Storage is charged per GB per month. Typical: Storing 10 GB costs approximately $0.23/month in S3 Standard (us-east-1).

- Pricing Tiers: S3 offers multiple storage classes (Standard, Intelligent-Tiering, Glacier, etc.), with different costs based on access frequency and retrieval times. Standard S3 fits most purposes.

Data transfer costs

- Uploading data to S3 is free.

- Downloading data (out of S3) incurs charges (~$0.09/GB). Be sure to take note of this fee, as it can add up fast for large datasets.

- In-region transfer (e.g., S3 to EC2) is free, while cross-region data transfer is charged (~$0.02/GB).

Request costs

- GET requests are $0.0004 per 1,000 requests. In the context of Amazon S3, “GET” requests refer to the action of retrieving or downloading data from an S3 bucket. Each time a file or object is accessed in S3, it incurs a small cost per request. This means that if you have code that reads data from S3 frequently, such as loading datasets repeatedly, each read operation counts as a GET request.

To calculate specific costs based on your needs, storage class, and region, refer to AWS’s S3 Pricing Information.

Challenge: Estimating Storage Costs

1. Estimate the total cost of storing 1 GB in S3 for one month assuming:

- Storage duration: 1 month

- Storage region: us-east-1

- Storage class: S3 Standard

- Data will be retrieved 100 times for model training and tuning

(

GETrequests) - Data will be deleted after the project concludes, incurring data retrieval and deletion costs

Hints

- S3 storage cost: $0.023 per GB per month (us-east-1)

- Data transfer cost (retrieval/deletion): $0.09 per GB (us-east-1 out to internet)

-

GETrequests cost: $0.0004 per 1,000 requests (each model training will incur oneGETrequest) - Check the AWS S3 Pricing page for more details.

2. Repeat the above calculation using the following dataset sizes: 10 GB, 100 GB, 1 TB (1024 GB)

Using the S3 Standard rate in us-east-1:

-

1 GB:

- Storage: 1 GB * $0.023 = $0.023

-

Retrieval/Deletion: 1 GB * $0.09 = $0.09

-

GET Requests: 100 requests * $0.0004 per 1,000 =

$0.00004

- Total Cost: $0.11304

-

10 GB:

- Storage: 10 GB * $0.023 = $0.23

-

Retrieval/Deletion: 10 GB * $0.09 = $0.90

-

GET Requests: 100 requests * $0.0004 per 1,000 =

$0.00004

- Total Cost: $1.13004

-

100 GB:

- Storage: 100 GB * $0.023 = $2.30

-

Retrieval/Deletion: 100 GB * $0.09 = $9.00

-

GET Requests: 100 requests * $0.0004 per 1,000 =

$0.00004

- Total Cost: $11.30004

-

1 TB (1024 GB):

- Storage: 1024 GB * $0.023 = $23.55

-

Retrieval/Deletion: 1024 GB * $0.09 = $92.16

-

GET Requests: 100 requests * $0.0004 per 1,000 =

$0.00004

- Total Cost: $115.71004

These costs assume no additional request charges beyond those for

retrieval, storage, and GET requests for training.

Removing unused data (complete after the workshop)

After you are done using your data, it’s important to practice good resource stewardship and remove the unneeded files/buckets.

Option 1: Delete data only (if you plan to reuse bucket for other datasets)

- Go to S3, navigate to the bucket.

- Select files to delete, then Actions > Delete.

Option 2: Delete the S3 bucket entirely (you no longer need the bucket or data)

- Select the bucket, click Actions > Delete.

- Type the bucket name to confirm deletion.

Please complete option 2 following this workshop. Deleting the bucket stops all costs associated with storage, requests, and data transfer.

- Use S3 for scalable, cost-effective, and flexible storage.

- EC2 storage is fairly uncommon, but may be suitable for small, temporary datasets.

- Track your S3 storage costs, data transfer, and requests to manage expenses.

- Regularly delete unused data or buckets to avoid ongoing costs.

Content from Notebooks as Controllers

Last updated on 2025-10-09 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do you set up and use SageMaker notebooks for machine learning tasks?

- How can you manage compute resources efficiently using SageMaker’s controller notebook approach?

Objectives

- Describe how to use SageMaker notebooks for ML workflows.

- Set up a Jupyter notebook instance as a controller to manage compute tasks.

- Use SageMaker SDK to launch training and tuning jobs on scalable instances.

Setting up our notebook environment

Amazon SageMaker provides a managed environment to simplify the process of building, training, and deploying machine learning models. In this episode, we’ll set up a SageMaker notebook instance—a Jupyter notebook hosted on AWS for managing SageMaker workflows.

Using the notebook as a controller

In this setup, the notebook instance functions as a

controller to manage more resource-intensive compute tasks. By

selecting a minimal instance (e.g., ml.t3.medium), you can

perform lightweight operations while leveraging the SageMaker

Python SDK to launch scalable compute instances for model

training, batch processing, and hyperparameter tuning. This approach

minimizes costs while accessing the full power of SageMaker for

demanding tasks.

We’ll follow these steps to create our first “SageMaker notebook instance”.

1. Navigate to SageMaker

- In the AWS Console, search for SageMaker.

- Recommended: Select the star icon next to Amazon SageMaker AI to save SageMaker as a bookmark in your AWS toolbar

- Select Amazon SageMaker AI

2. Create a new notebook instance

- In the SageMaker left-side menu, click on Notebooks, then click Create notebook instance.

- Notebook name: To easily track this resource in our shared account, please use the following naming convention: “TeamName-LastnameFirstname-NotebookPurpose”. For example, “sinkorswin-DoeJohn-TrainClassifier”. Can include hyphens, but not spaces.

-

Instance type: SageMaker notebooks run on AWS EC2

instances. The instance type determines the compute resources allocated

to the notebook. Since our notebook will act as a low-resource

“controller”, we’ll select a small instance such as

ml.t3.medium(4 GB RAM, $0.04/hour)- This keeps costs low while allowing us to launch separate

training/tuning jobs on more powerful instances when needed.

- For guidance on common instances for ML procedures, refer to our

supplemental Instances

for ML webpage.

- This keeps costs low while allowing us to launch separate

training/tuning jobs on more powerful instances when needed.

- Platform identifier: This is an internal AWS setting related to the environment version and underlying platform. You can leave this as the default.

-

Permissions and encryption:

-

IAM role: For this workshop, we have pre-configured

the “ml-sagemmaker-use” role to enable access to AWS services like

SageMaker, with some restrictions to prevent overuse/misuse of

resources. Select the “ml-sagemmaker-use” role. Outside of the workshop,

you create/select a role that includes the

AmazonSageMakerFullAccesspolicy. -

Root access: Determines whether the user can run

administrative commands within the notebook instance. You should

Enable root access to allow installing additional

packages if/when needed.

- Encryption key (skip): While we won’t use this feature for the workshop, it is possible to specify a KMS key for encrypting data at rest if needed.

-

IAM role: For this workshop, we have pre-configured

the “ml-sagemmaker-use” role to enable access to AWS services like

SageMaker, with some restrictions to prevent overuse/misuse of

resources. Select the “ml-sagemmaker-use” role. Outside of the workshop,

you create/select a role that includes the

- Network (skip): Networking settings are optional. Configure them if you’re working within a specific VPC or need network customization.

- Git repositories configuration (skip): You don’t need to complete this configuration. Instead, we’ll run a clone command from our notebook later to get our repo setup. This approach is a common strategy (allowing some flexiblity in which repo you use for the notebook).

- Tags (NOT OPTIONAL): Adding tags helps track and organize resources for billing and management. This is particularly useful when you need to break down expenses by project, task, or team. To help track costs on our shared account, please use the tags found in the below image.

- Click Create notebook instance. It may take a few minutes for the instance to start. Once its status is InService, you can open the notebook instance and start coding.

Load pre-filled Jupyter notebooks

Once your newly created instance shows as

InService, open the instance in Jupyter Lab. From there, we

can create as many Jupyter notebooks as we would like within the

instance environment.

We will then select the standard python3 environment (conda_python3) to start our first .ipynb notebook (Jupyter notebook). We can use the standard conda_python3 environment since we aren’t doing any training/tuning just yet.

Load pre-filled Jupyter notebooks

Within the Jupyter notebook, run the following command to clone the lesson repo into our Jupyter environment:

Then, navigate to

/ML_with_AWS_SageMaker/notebooks/Accessing-S3-via-SageMaker-notebooks.ipynb

to begin the first notebook.

- Use a minimal SageMaker notebook instance as a controller to manage larger, resource-intensive tasks.

- Launch training and tuning jobs on scalable instances using the SageMaker SDK.

- Tags can help track costs effectively, especially in multi-project or team settings.

- Use the SageMaker SDK documentation to explore additional options for managing compute resources in AWS.

Content from Accessing and Managing Data in S3 with SageMaker Notebooks

Last updated on 2025-10-09 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I load data from S3 into a SageMaker notebook?

- How do I monitor storage usage and costs for my S3 bucket?

- What steps are involved in pushing new data back to S3 from a notebook?

Objectives

- Read data directly from an S3 bucket into memory in a SageMaker notebook.

- Check storage usage and estimate costs for data in an S3 bucket.

- Upload new files from the SageMaker environment back to the S3 bucket.

Set up AWS environment

To begin each notebook, it’s important to set up an AWS environment that will allow seamless access to the necessary cloud resources. Here’s what we’ll do to get started:

Define the Role: We’ll use

get_execution_role()to retrieve the IAM role associated with the SageMaker instance. This role specifies the permissions needed for interacting with AWS services like S3, which allows SageMaker to securely read from and write to storage buckets.Initialize the SageMaker Session: Next, we’ll create a

sagemaker.Session()object, which will help manage and track the resources and operations we use in SageMaker, such as training jobs and model artifacts. The session acts as a bridge between the SageMaker SDK commands in our notebook and AWS services.Set Up an S3 Client using boto3: Using

boto3, we’ll initialize an S3 client for accessing S3 buckets directly. Boto3 is the official AWS SDK for Python, allowing developers to interact programmatically with AWS services like S3, EC2, and Lambda.

Starting with these initializations prepares our notebook environment to efficiently interact with AWS resources for model development, data management, and deployment.

PYTHON

import boto3

import sagemaker

from sagemaker import get_execution_role

# Initialize the SageMaker role, session, and s3 client

role = sagemaker.get_execution_role() # specifies your permissions to use AWS tools

session = sagemaker.Session()

s3 = boto3.client('s3')Preview variable details.

PYTHON

# Print relevant details

print(f"Execution Role: {role}") # Displays the IAM role being used

bucket_names = [bucket["Name"] for bucket in s3.list_buckets()["Buckets"]]

print(f"Available S3 Buckets: {bucket_names}") # Shows the default S3 bucket assigned to SageMaker

print(f"AWS Region: {session.boto_region_name}") # Prints the region where the SageMaker session is runningReading data from S3

You can either (A) read data from S3 into memory or (B) download a copy of your S3 data into your notebook instance. Since we are using SageMaker notebooks as controllers—rather than performing training or tuning directly in the notebook—the best practice is to read data directly from S3 whenever possible. However, there are cases where downloading a local copy may be useful. We’ll show you both strategies.

A) Reading data directly from S3 into memory

This is the recommended approach for most workflows. By keeping data in S3 and reading it into memory when needed, we avoid local storage constraints and ensure that our data remains accessible for SageMaker training and tuning jobs.

Pros:

- Scalability: Data remains in S3, allowing multiple training/tuning jobs to access it without duplication.

- Efficiency: No need to manage local copies or manually clean up storage.

- Cost-effective: Avoids unnecessary instance storage usage.

Cons:

- Network dependency: Requires internet access to S3.

- Potential latency: Reading large datasets repeatedly from S3 may introduce small delays. This approach works best if you only need to load data once or infrequently.

Example: Reading data from S3 into memory

Our data is stored on an S3 bucket called ‘teamname-name-dataname’ (e.g., sinkorswim-doejohn-titanic). We can use the following code to read data directly from S3 into memory in the Jupyter notebook environment, without actually downloading a copy of train.csv as a local file.

PYTHON

import pandas as pd

# Define the S3 bucket and object key

bucket_name = 'sinkorswim-doejohn-titanic' # replace with your S3 bucket name

# Read the train data from S3

key = 'titanic_train.csv' # replace with your object key

response = s3.get_object(Bucket=bucket_name, Key=key)

train_data = pd.read_csv(response['Body'])

# Read the test data from S3

key = 'titanic_test.csv' # replace with your object key

response = s3.get_object(Bucket=bucket_name, Key=key)

test_data = pd.read_csv(response['Body'])

# check shape

print(train_data.shape)

print(test_data.shape)

# Inspect the first few rows of the DataFrame

train_data.head()B) Download copy into notebook environment

In some cases, downloading a local copy of the dataset may be useful, such as when performing repeated reads in an interactive notebook session.

Pros:

- Faster access for repeated operations: Avoids repeated S3 requests.

- Works offline: Useful if running in an environment with limited network access.

Cons:

- Consumes instance storage: Notebook instances have limited space.

- Requires manual cleanup: Downloaded files remain until deleted.

Example

PYTHON

# Define the S3 bucket and file location

key = "titanic_train.csv" # Path to your file in the S3 bucket

local_file_path = "/home/ec2-user/SageMaker/titanic_train.csv" # Local path to save the file

# Initialize the S3 client and download the file

s3.download_file(bucket_name, key, local_file_path)

!lsNote: You may need to hit refresh on the file explorer panel to the left to see this file. If you get any permission issues…

- check that you have selected the appropriate policy for this notebook

- check that your bucket has the appropriate policy permissions

Check the current size and storage costs of bucket

It’s a good idea to periodically check how much storage you have used in your bucket. You can do this from a Jupyter notebook in SageMaker by using the Boto3 library, which is the AWS SDK for Python. This will allow you to calculate the total size of objects within a specified bucket.

The code below will calculate your bucket size for you. Here is a breakdown of the important pieces in the next code section:

- Paginator: Since S3 buckets can contain many objects, we use a paginator to handle large listings.

-

Size calculation: We sum the

Sizeattribute of each object in the bucket. -

Unit conversion: The size is given in bytes, so

dividing by

1024 ** 2converts it to megabytes (MB).

Note: If your bucket has very large objects or you want to check specific folders within a bucket, you may want to refine this code to only fetch certain objects or folders.

PYTHON

# Initialize the total size counter (bytes)

total_size_bytes = 0

# Use a paginator to handle large bucket listings

# This ensures that even if the bucket contains many objects, we can retrieve all of them

paginator = s3.get_paginator("list_objects_v2")

# Iterate through all pages of object listings

for page in paginator.paginate(Bucket=bucket_name):

# 'Contents' contains the list of objects in the current page, if available

for obj in page.get("Contents", []):

total_size_bytes += obj["Size"] # Add each object's size to the total

# Convert the total size to gigabytes for cost estimation

total_size_gb = total_size_bytes / (1024 ** 3)

# Convert the total size to megabytes for easier readability

total_size_mb = total_size_bytes / (1024 ** 2)

# Print the total size in MB

print(f"Total size of bucket '{bucket_name}': {total_size_mb:.2f} MB")

# Print the total size in GB

#print(f"Total size of bucket '{bucket_name}': {total_size_gb:.2f} GB")Using helper functions from GitHub

We have added code to calculate bucket size to a helper function

called get_s3_bucket_size(bucket_name) for your

convenience. There are also some other helper functions in the

AWS_helpers repo to assist you with common AWS/SageMaker workflows.

We’ll show you how to clone this code into your notebook

environment.

Directory setup

Let’s make sure we’re starting in the root directory of this instance, so that we all have our AWS_helpers.py file located in the same path (/test_AWS/scripts/AWS_helpers.py)

To clone the repo to our Jupyter notebook, use the following code.

PYTHON

!git clone https://github.com/UW-Madison-DataScience/AWS_helpers.git # downloads AWS_helpers folder/repo (refresh file explorer to see)Our AWS_helpers.py file can be found in

AWS_helpers/helpers.py. With this file downloaded, you can

call this function via…

Check storage costs of bucket

To estimate the storage cost of your Amazon S3 bucket directly from a Jupyter notebook in SageMaker, you can use the following approach. This method calculates the total size of the bucket and estimates the monthly storage cost based on AWS S3 pricing.

Note: AWS S3 pricing varies by region and storage class. The example below uses the S3 Standard storage class pricing for the US East (N. Virginia) region as of November 1, 2024. Please verify the current pricing for your specific region and storage class on the AWS S3 Pricing page.

PYTHON

# AWS S3 Standard Storage pricing for US East (N. Virginia) region

# Pricing tiers as of November 1, 2024

first_50_tb_price_per_gb = 0.023 # per GB for the first 50 TB

next_450_tb_price_per_gb = 0.022 # per GB for the next 450 TB

over_500_tb_price_per_gb = 0.021 # per GB for storage over 500 TB

# Calculate the cost based on the size

if total_size_gb <= 50 * 1024:

# Total size is within the first 50 TB

cost = total_size_gb * first_50_tb_price_per_gb

elif total_size_gb <= 500 * 1024:

# Total size is within the next 450 TB

cost = (50 * 1024 * first_50_tb_price_per_gb) + \

((total_size_gb - 50 * 1024) * next_450_tb_price_per_gb)

else:

# Total size is over 500 TB

cost = (50 * 1024 * first_50_tb_price_per_gb) + \

(450 * 1024 * next_450_tb_price_per_gb) + \

((total_size_gb - 500 * 1024) * over_500_tb_price_per_gb)

print(f"Estimated monthly storage cost: ${cost:.5f}")

print(f"Estimated annual storage cost: ${cost*12:.5f}")For your convenience, we have also added this code to a helper function.

PYTHON

monthly_cost, storage_size_gb = helpers.calculate_s3_storage_cost(bucket_name)

print(f"Estimated monthly cost ({storage_size_gb:.4f} GB): ${monthly_cost:.5f}")

print(f"Estimated annual cost ({storage_size_gb:.4f} GB): ${monthly_cost*12:.5f}")Important Considerations:

-

Pricing Tiers: AWS S3 pricing is tiered. The first

50 TB per month is priced at

$0.023 per GB, the next 450 TB at$0.022 per GB, and storage over 500 TB at$0.021 per GB. Ensure you apply the correct pricing tier based on your total storage size. - Region and Storage Class: Pricing varies by AWS region and storage class. The example above uses the S3 Standard storage class pricing for the US East (N. Virginia) region. Adjust the pricing variables if your bucket is in a different region or uses a different storage class.

- Additional Costs: This estimation covers storage costs only. AWS S3 may have additional charges for requests, data retrievals, and data transfers. For a comprehensive cost analysis, consider these factors as well.

For detailed and up-to-date information on AWS S3 pricing, please refer to the AWS S3 Pricing page.

Writing output files to S3

As your analysis generates new files or demands additional

documentation, you can upload files to your bucket as demonstrated

below. For this demo, you can create a blank Notes.txt file

to upload to your bucket. To do so, go to File ->

New -> Text file, and save it out

as Notes.txt.

PYTHON

# Define the S3 bucket name and the file paths

notes_file_path = "Notes.txt" # assuming your file is in root directory of jupyter notebook (check file explorer tab)

# Upload the training file to a new folder called "docs". You can also just place it in the bucket's root directory if you prefer (remove docs/ in code below).

s3.upload_file(notes_file_path, bucket_name, "docs/Notes.txt")

print("Files uploaded successfully.")After uploading, we can view the objects/files available on our bucket using…

PYTHON

# List and print all objects in the bucket

response = s3.list_objects_v2(Bucket=bucket_name)

# Check if there are objects in the bucket

if 'Contents' in response:

for obj in response['Contents']:

print(obj['Key']) # Print the object's key (its path in the bucket)

else:

print("The bucket is empty or does not exist.")Alternatively, we can substitute this for a helper function call as well.

- Load data from S3 into memory for efficient storage and processing.

- Periodically check storage usage and costs to manage S3 budgets.

- Use SageMaker to upload analysis results and maintain an organized workflow.

Content from Using a GitHub Personal Access Token (PAT) to Push/Pull from a SageMaker Notebook

Last updated on 2025-11-24 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 35 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I securely push/pull code to and from GitHub within a SageMaker notebook?

- What steps are necessary to set up a GitHub PAT for authentication in SageMaker?

- How can I convert notebooks to

.pyfiles and ignore.ipynbfiles in version control?

Objectives

- Configure Git in a SageMaker notebook to use a GitHub Personal Access Token (PAT) for HTTPS-based authentication.

- Securely handle credentials in a notebook environment using

getpass. - Convert

.ipynbfiles to.pyfiles for better version control practices in collaborative projects.

Open prefilled .ipynb notebook

Open the notebook from:

/ML_with_AWS_SageMaker/notebooks/Interacting-with-code-repo.ipynb.

Step 0: Initial setup

In this episode, we’ll demonstrate how to push code to GitHub from a SageMaker Jupyter Notebook.

To begin, we will first create a GitHub repo that we have read/write access to. Feel free to supplement the instructions below with your own personal GitHub repo if you have one ou want to use with SageMaker already. Else, we can simply create a fork of AWS_helpers repo. You may have completed this step already if you completed all workshop setup steps.

- Navigate to https://github.com/UW-Madison-DataScience/AWS_helpers

- Click the fork button

- Select yourself as the owner of the fork, and “Copy the main branch only” selected. You will only need the main branch.

Next, let’s make sure we’re starting at the same directory. Back in our SageMaker Jupyter Lab notebook, change directory to the root directory of this instance before going further.

Then, clone the fork. Replace “USERNAME” below with your GitHub username.

Step 1: Using a GitHub personal access token (PAT) to push/pull from a SageMaker notebook

When working in SageMaker notebooks, you may often need to push code updates to GitHub repositories. However, SageMaker notebooks are typically launched with temporary instances that don’t persist configurations, including SSH keys, across sessions. This makes HTTPS-based authentication, secured with a GitHub Personal Access Token (PAT), a practical solution. PATs provide flexibility for authentication and enable seamless interaction with both public and private repositories directly from your notebook.

Important Note: Personal access tokens are powerful credentials that grant specific permissions to your GitHub account. To ensure security, only select the minimum necessary permissions and handle the token carefully.

Generate a personal access token (PAT) on GitHub

- Go to Settings by clicking on your profile picture in the upper-right corner of GitHub.

- Click Developer settings at the very bottom of the left sidebar.

- Select Personal access tokens, then click Tokens (classic).

- Click Generate new token (classic).

- Give your token a descriptive name (e.g., “SageMaker Access Token”) and set an expiration date if desired for added security.

-

Select the minimum permissions needed:

-

For public repositories: Choose only

public_repo. -

For private repositories: Choose

repo(full control of private repositories). - Optional permissions, if needed:

-

repo:status: Access commit status (if checking status checks). -

workflow: Update GitHub Actions workflows (only if working with GitHub Actions).

-

-

For public repositories: Choose only

- Click Generate token and copy it immediately—you won’t be able to see it again once you leave the page.

Caution: Treat your PAT like a password. Avoid sharing it or exposing it in your code. Store it securely (e.g., via a password manager like LastPass) and consider rotating it regularly.

Use getpass to prompt for username and PAT

The getpass library allows you to input your GitHub

username and PAT without exposing them in the notebook. This approach

ensures you’re not hardcoding sensitive information.

PYTHON

import getpass

# Prompt for GitHub username and PAT securely

username = input("GitHub Username: ")

token = getpass.getpass("GitHub Personal Access Token (PAT): ")Note: After running, you may want to comment out the above code so that you don’t have to enter in your login every time you run your whole notebook

Step 2: Configure Git settings

In your SageMaker or Jupyter notebook environment, run the following commands to set up your Git user information.

Setting this globally (--global) will ensure the

configuration persists across all repositories in the environment. If

you’re working in a temporary environment, you may need to re-run this

configuration after a restart.

PYTHON

!git config --global user.name "Your name" # This is your GitHub username (or just your name), which will appear in the commit history as the author of the changes.

!git config --global user.email your_email@wisc.edu # This should match the email associated with your GitHub account so that commits are properly linked to your profile.Step 3: Convert json .ipynb files to .py

We’d like to track our notebook files within our repo fork. However,

to avoid tracking ipynb files directly, which are formatted as json, we

may want to convert our notebook to .py first (plain text). Converting

notebooks to .py files helps maintain code (and

version-control) readability and minimizes potential issues with

notebook-specific metadata in Git history.

Benefits of converting to .py before Committing

-

Cleaner version control:

.pyfiles have cleaner diffs and are easier to review and merge in Git. - Script compatibility: Python files are more compatible with other environments and can run easily from the command line.

-

Reduced repository size:

.pyfiles are generally lighter than.ipynbfiles since they don’t store outputs or metadata.

Here’s how to convert .ipynb files to .py

in SageMaker without needing to export or download files.

- First, install Jupytext.

- Then, run the following command in a notebook cell to convert both

of our notebooks to

.pyfiles

PYTHON

# Adjust filename(s) if you used something different

!jupytext --to py Interacting-with-S3.ipynbSH

[jupytext] Reading Interacting-with-S3.ipynb in format ipynb

[jupytext] Writing Interacting-with-S3.py- If you have multiple notebooks to convert, you can automate the

conversion process by running this code, which converts all

.ipynbfiles in the current directory to.pyfiles:

PYTHON

import subprocess

import os

# List all .ipynb files in the directory

notebooks = [f for f in os.listdir() if f.endswith('.ipynb')]

# Convert each notebook to .py using jupytext

for notebook in notebooks:

output_file = notebook.replace('.ipynb', '.py')

subprocess.run(["jupytext", "--to", "py", notebook, "--output", output_file])

print(f"Converted {notebook} to {output_file}")For convenience, we have placed this code inside a

convert_files() function in helpers.py.

Once converted, move our new .py file to the AWS_helpers folder using the file explorer panel in Jupyter Lab.

Step 4. Add and commit .py files

- Check status of repo. Make sure you’re in the repo folder before running the next step.

- Add and commit changes

PYTHON

!git add . # you may also add files one at a time, for further specificity over the associated commit message

!git commit -m "Updates from Jupyter notebooks" # in general, your commit message should be more specific!- Check status

Step 5. Adding .ipynb to gitigore

Adding .ipynb files to .gitignore is a good

practice if you plan to only commit .py scripts. This will

prevent accidental commits of Jupyter Notebook files across all

subfolders in the repository.

Here’s how to add .ipynb files to

.gitignore to ignore them project-wide:

- Check working directory: First make sure we’re in the repo folder

-

Create the

.gitignorefile: This file will be hidden in Jupyter (since it starts with “.”), but you can verify it exists usingls.

-

Add

.ipynbfiles to.gitignore: You can add this line using a command within your notebook:

PYTHON

with open(".gitignore", "a") as gitignore:

gitignore.write("\n# Ignore all Jupyter Notebook files\n*.ipynb\n")View file contents

- Ignore other common temp files While we’re at it, let’s ignore other common files that can clutter repos, such as cache folders and temporary files.

PYTHON

with open(".gitignore", "a") as gitignore:

gitignore.write("\n# Ignore cache and temp files\n__pycache__/\n*.tmp\n*.log\n")View file contents

-

Add and commit the

.gitignorefile:

Add and commit the updated .gitignore file to ensure

it’s applied across the repository.

This setup will:

- Prevent all

.ipynbfiles from being tracked by Git. - Keep your repository cleaner, containing only

.pyscripts for easier version control and reduced repository size.

Step 6. Merging local changes with remote/GitHub

Our local changes have now been committed, and we can begin the process of mergining with the remote main branch. Before we try to push our changes, it’s good practice to first to a pull. This is critical when working on a collaborate repo with multiple users, so that you don’t miss any updates from other team members.

1. Pull the latest changes from the main branch

There are a few different options for pulling the remote code into your local version. The best pull strategy depends on your workflow and the history structure you want to maintain. Here’s a breakdown to help you decide:

- Merge (pull.rebase false): Combines the remote changes into your

local branch as a merge commit.

- Use if: You’re okay with having merge commits in your history, which indicate where you pulled in remote changes. This is the default and is usually the easiest for team collaborations, especially if conflicts arise.

- Rebase (pull.rebase true): Replays your local changes on top of the

updated main branch, resulting in a linear history.

- Use if: You prefer a clean, linear history without merge commits. Rebase is useful if you like to keep your branch history as if all changes happened sequentially.

- Fast-forward only (pull.ff only): Only pulls if the local branch can

fast-forward to the remote without diverging (no new commits locally).

- Use if: You only want to pull updates if no additional commits have been made locally. This can be helpful to avoid unintended merges when your branch hasn’t diverged.

Recommended for Most Users

If you’re collaborating and want simplicity, merge (pull.rebase false) is often the most practical option. This will ensure you get remote changes with a merge commit that captures the history of integration points. For those who prefer a more streamlined history and are comfortable with Git, rebase (pull.rebase true) can be ideal but may require more careful conflict handling.

PYTHON

!git config pull.rebase false # Combines the remote changes into your local branch as a merge commit.

!git pull origin mainIf you get merge conflicts, be sure to resolve those before moving forward (e.g., use git checkout -> add -> commit). You can skip the below code if you don’t have any conflicts.

PYTHON

# Keep your local changes in one conflicting file

# !git checkout --ours Interacting-with-git.py

# Keep remote version for the other conflicting file

# !git checkout --theirs Interacting-with-git.py

# # Stage the files to mark the conflicts as resolved

# !git add Interacting-with-git.py

# # Commit the merge result

# !git commit -m "Resolved merge conflicts by keeping local changes"2. Push changes using PAT creditials

PYTHON

# Push with embedded credentials from getpass (avoids interactive prompt)

github_url = f'github.com/{username}/AWS_helpers.git' # The full address for your fork can be found under Code -> Clone -> HTTPS (remote the https:// before the rest of the address)

!git push https://{username}:{token}@{github_url} mainAfter pushing, you can navigate back to your fork on GitHub to verify everything worked (e.g., https://github.com/username/AWS_helpers/tree/main)

Step 7: Pulling .py files and converting back to notebook format

Let’s assume you’ve taken a short break from your work, and others on

your team have made updates to your .py files on the remote main branch.

If you’d like to work with notebook files again, you can again use

jupytext to convert your .py files back to

.ipynb.

- First, pull any updates from the remote main branch.

PYTHON

!git config pull.rebase false # Combines the remote changes into your local branch as a merge commit.

!git pull origin main- We can then use jupytext again to convert in the other direction

(.py to .ipynb). This command will create

Interacting-with-S3.ipynbin the current directory, converting the Python script to a Jupyter Notebook format. Jupytext handles the conversion gracefully without expecting the.pyfile to be in JSON format.

Applying to all .py files

To convert all of your .py files to notebooks, you can use our helper function as follows

- Use a GitHub PAT for HTTPS-based authentication in temporary SageMaker notebook instances.

- Securely enter sensitive information in notebooks using

getpass. - Converting

.ipynbfiles to.pyfiles helps with cleaner version control and easier review of changes. - Adding

.ipynbfiles to.gitignorekeeps your repository organized and reduces storage.

Content from Training Models in SageMaker: Intro

Last updated on 2025-12-18 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What are the differences between local training and SageMaker-managed training?

- How do Estimator classes in SageMaker streamline the training process for various frameworks?

- How does SageMaker handle data and model parallelism, and when should each be considered?

Objectives

- Understand the difference between training locally in a SageMaker notebook and using SageMaker’s managed infrastructure.

- Learn to configure and use SageMaker’s Estimator classes for different frameworks (e.g., XGBoost, PyTorch, SKLearn).

- Understand data and model parallelism options in SageMaker, including when to use each for efficient training.

- Compare performance, cost, and setup between custom scripts and built-in images in SageMaker.

- Conduct training with data stored in S3 and monitor training job status using the SageMaker console.

Initial setup

1. Open prefilled .ipynb notebook

Open the notebook from:

/ML_with_AWS_SageMaker/notebooks/Training-models-in-SageMaker-notebooks.ipynb

2. CD to instance home directory

So we all can reference the helper functions using the same path, CD to…

3. Initialize SageMaker environment

This code initializes the AWS SageMaker environment by defining the SageMaker role and S3 client. It also specifies the S3 bucket and key for accessing the Titanic training dataset stored in an S3 bucket.

Boto3 API

Boto3 is the official AWS SDK for Python, allowing developers to interact programmatically with AWS services like S3, EC2, and Lambda. It provides both high-level and low-level APIs, making it easy to manage AWS resources and automate tasks. With built-in support for paginators, waiters, and session management, Boto3 simplifies working with AWS credentials, regions, and IAM permissions. It’s ideal for automating cloud operations and integrating AWS services into Python applications.

PYTHON

import boto3

import pandas as pd

import sagemaker

from sagemaker import get_execution_role

# Initialize the SageMaker role (will reflect notebook instance's policy)

role = sagemaker.get_execution_role()

print(f'role = {role}')

# Initialize an S3 client to interact with Amazon S3, allowing operations like uploading, downloading, and managing objects and buckets.

s3 = boto3.client('s3')

# Define the S3 bucket that we will load from

bucket_name = 'sinkorswim-doejohn-titanic' # replace with your S3 bucket name

# Define train/test filenames

train_filename = 'titanic_train.csv'

test_filename = 'titanic_test.csv'Create a SageMaker session to manage interactions with Amazon SageMaker, such as training jobs, model deployments, and data input/output.

PYTHON

region = "us-east-2" # United States (Ohio). Make sure this matches what you see near top right of AWS Console menu

boto_session = boto3.Session(region_name=region) # Create a Boto3 session that ensures all AWS service calls (including SageMaker) use the specified region

session = sagemaker.Session(boto_session=boto_session)Testing train.py on this notebook’s instance

In this next section, we will learn how to take a model training script that was written/designed to run locally, and deploy it to more powerful instances (or many instances) using SageMaker. This is helpful for machine learning jobs that require extra power, GPUs, or benefit from parallelization. However, before we try exploiting this extra power, it is essential that we test our code thoroughly! We don’t want to waste unnecessary compute cycles and resources on jobs that produce bugs rather than insights.

General guidelines for testing ML pipelines before scaling

- Run tests locally first (if feasible) to avoid unnecessary AWS charges. Here, we assume that local tests are not feasible due to limited local resources. Instead, we use our SageMaker instance to test our script on a minimally sized EC2 instance.

- Use a small dataset subset (e.g., 1-5% of data) to catch issues early and speed up tests.

- Start with a small/cheap instance before committing to larger resources. Visit the Instances for ML page for guidance.

- Log everything to track training times, errors, and key metrics.

- Verify correctness first before optimizing hyperparameters or scaling.

What tests should we do before scaling?

Before scaling to mutliple or more powerful instances (e.g., training on larger/multiple datsets in parallel or tuning hyperparameters in parallel), it’s important to run a few quick sanity checks to catch potential issues early. In your group, discuss:

- Which checks do you think are most critical before scaling up?

- What potential issues might we miss if we skip this step?

Which checks do you think are most critical before scaling up?

-

Data loads correctly – Ensure the dataset loads

without errors, expected columns exist, and missing values are handled

properly.

-

Overfitting check – Train on a small dataset (e.g.,

100 rows). If it doesn’t overfit, there may be a data or model setup

issue.

-

Loss behavior check – Verify that training loss

decreases over time and doesn’t diverge.

- Training time estimate – Run on a small subset to estimate how long full training will take.

- Memory estimate - Estimate the memory needs of the algorithm/model you’re using, and understand how this scales with input size.

- Save & reload test – Ensure the trained model can be saved, reloaded, and used for inference without errors.

What potential issues might we miss if we skip the above checks?

-

Silent data issues – Missing values, unexpected

distributions, or incorrect labels could degrade model

performance.

-

Code bugs at scale – Small logic errors might not

break on small tests but could fail with larger datasets.

-

Inefficient training runs – Without estimating

runtime, jobs may take far longer than expected, wasting AWS

resources.

-

Memory or compute failures – Large datasets might

exceed instance memory limits, causing crashes or slowdowns.

- Model performance issues – If a model doesn’t overfit a small dataset, there may be problems with features, training logic, or hyperparameters.

Know Your Data Before Modeling

The sanity checks above focus on validating the code, but a model is only as good as the data it’s trained on. A deeper look at feature distributions, correlations, and potential biases is critical before scaling up. We won’t cover that here, but it’s essential to keep in mind for any ML/AI practitioner.

Understanding the XGBoost Training Script

Take a moment to review the AWS_helpers/train_xgboost.py

script we just cloned into our notebook. This script handles

preprocessing, training, and saving an XGBoost model, while also

adapting to both local and SageMaker-managed environments.

Try answering the following questions:

Data Preprocessing: What transformations are applied to the dataset before training?

Training Function: What does the

train_model()function do? Why do we print the training time?Command-Line Arguments: What is the purpose of

argparsein this script? How would you modify the script if you wanted to change the number of training rounds?Handling Local vs. SageMaker Runs: How does the script determine whether it is running in a SageMaker training job or locally (within this notebook’s instance)?

Training and Saving the Model: What format is the dataset converted to before training, and why? How is the trained model saved, and where will it be stored?

After reviewing, discuss any questions or observations with your group.

Data Preprocessing: The script fills missing values (

Agewith median,Embarkedwith mode), converts categorical variables (SexandEmbarked) to numerical values, and removes columns that don’t contribute to prediction (Name,Ticket,Cabin).Training Function: The

train_model()function takes the training dataset (dtrain), applies XGBoost training with the specified hyperparameters, and prints the training time. Printing training time helps compare different runs and ensures that scaling decisions are based on performance metrics.Command-Line Arguments:

argparseallows passing parameters likemax_depth,eta,num_round, etc., at runtime without modifying the script. To change the number of training rounds, you would update the--num_roundargument when running the script:python train_xgboost.py --num_round 200Handling Local vs. SageMaker Runs: The script uses

os.environ.get("SM_CHANNEL_TRAIN", ".")andos.environ.get("SM_MODEL_DIR", ".")to detect whether it’s running in SageMaker.SM_CHANNEL_TRAINis the directory where SageMaker stores input training data, andSM_MODEL_DIRis the directory where trained models should be saved. If these environment variables are not set (e.g., running locally), the script defaults to"."(current directory).Training and Saving the Model: The dataset is converted into XGBoost’s

DMatrixformat, which is optimized for memory and computation efficiency. The trained model is saved usingjoblib.dump()toxgboost-model, stored either in the SageMakerSM_MODEL_DIR(if running in SageMaker) or in the local directory.

Download data into notebook environment

It can be convenient to have a copy of the data (i.e., one that you store in your notebook’s instance) to allow us to test our code before scaling things up.

While we demonstrate how to download data into the notebook environment for testing our code (previously setup for local ML pipelines), keep in mind that S3 is the preferred location for dataset storage in a scalable ML pipeline.

Run the next code chunk to download data from S3 to notebook environment. You may need to hit refresh on the file explorer panel to the left to see this file. If you get any permission issues…

- check that you have selected the appropriate policy for this notebook

- check that your bucket has the appropriate policy permissions

PYTHON

# Define the S3 bucket and file location

file_key = f"{train_filename}" # Path to your file in the S3 bucket

local_file_path = f"./{train_filename}" # Local path to save the file

# Download the file using the s3 client variable we initialized earlier

s3.download_file(bucket_name, file_key, local_file_path)

print("File downloaded:", local_file_path)We can do the same for the test set.

PYTHON

# Define the S3 bucket and file location

file_key = f"{test_filename}" # Path to your file in the S3 bucket. W

local_file_path = f"./{test_filename}" # Local path to save the file

# Initialize the S3 client and download the file

s3.download_file(bucket_name, file_key, local_file_path)

print("File downloaded:", local_file_path)Logging runtime & instance info

To compare our local runtime with future experiments, we’ll need to know what instance was used, as this will greatly impact runtime in many cases. We can extract the instance name for this notebook using…

PYTHON

# Replace with your notebook instance name.

# This does NOT refer to specific ipynb files, but to the SageMaker notebook instance.

notebook_instance_name = 'sinkorswim-DoeJohn-TrainClassifier'

# Make sure this matches what you see near top right of AWS Console menu

region = "us-east-2" # United States (Ohio)

# Initialize SageMaker client

sagemaker_client = boto3.client('sagemaker', region_name=region)

# Describe the notebook instance

response = sagemaker_client.describe_notebook_instance(NotebookInstanceName=notebook_instance_name)

# Display the status and instance type

print(f"Notebook Instance '{notebook_instance_name}' status: {response['NotebookInstanceStatus']}")

local_instance = response['InstanceType']

print(f"Instance Type: {local_instance}")Helper: get_notebook_instance_info()

You can also use the get_notebook_instance_info()

function found in AWS_helpers.py to retrieve this info for

your own project.

PYTHON

import AWS_helpers.helpers as helpers

helpers.get_notebook_instance_info(notebook_instance_name, region)Test train.py on this notebook’s instance (or when possible, on your own machine) before doing anything more complicated (e.g., hyperparameter tuning on multiple instances)

Local test

PYTHON

import time as t # we'll use the time package to measure runtime

start_time = t.time()

# Define your parameters. These python vars wil be passed as input args to our train_xgboost.py script using %run

max_depth = 3 # Sets the maximum depth of each tree in the model to 3. Limiting tree depth helps control model complexity and can reduce overfitting, especially on small datasets.

eta = 0.1 # Sets the learning rate to 0.1, which scales the contribution of each tree to the final model. A smaller learning rate often requires more rounds to converge but can lead to better performance.

subsample = 0.8 # Specifies that 80% of the training data will be randomly sampled to build each tree. Subsampling can help with model robustness by preventing overfitting and increasing variance.

colsample_bytree = 0.8 # Specifies that 80% of the features will be randomly sampled for each tree, enhancing the model's ability to generalize by reducing feature reliance.

num_round = 100 # Sets the number of boosting rounds (trees) to 100. More rounds typically allow for a more refined model, but too many rounds can lead to overfitting.

train_file = 'titanic_train.csv' # Points to the location of the training data

# Use f-strings to format the command with your variables

%run AWS_helpers/train_xgboost.py --max_depth {max_depth} --eta {eta} --subsample {subsample} --colsample_bytree {colsample_bytree} --num_round {num_round} --train {train_file}

# Measure and print the time taken

print(f"Total local runtime: {t.time() - start_time:.2f} seconds, instance_type = {local_instance}")Training on this relatively small dataset should take less than a minute, but as we scale up with larger datasets and more complex models in SageMaker, tracking both training time and total runtime becomes essential for efficient debugging and resource management.

Note: Our code above includes print statements to monitor dataset size, training time, and total runtime, which provides insights into resource usage for model development. We recommend incorporating similar logging to track not only training time but also total runtime, which includes additional steps like data loading, evaluation, and saving results. Tracking both can help you pinpoint bottlenecks and optimize your workflow as projects grow in size and complexity, especially when scaling with SageMaker’s distributed resources.

Sanity check: Quick evaluation on test set

This next section isn’t SageMaker specific, but it does serve as a good sanity check to ensure our model is training properly. Here’s how you would apply the outputted model to your test set using your local notebook instance.

PYTHON

import xgboost as xgb

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

import joblib

from AWS_helpers.train_xgboost import preprocess_data

# Load the test data

test_data = pd.read_csv('./titanic_test.csv')

# Preprocess the test data using the imported preprocess_data function

X_test, y_test = preprocess_data(test_data)

# Convert the test features to DMatrix for XGBoost

dtest = xgb.DMatrix(X_test)

# Load the trained model from the saved file

model = joblib.load('./xgboost-model')

# Make predictions on the test set

preds = model.predict(dtest)

predictions = np.round(preds) # Round predictions to 0 or 1 for binary classification

# Calculate and print the accuracy of the model on the test data

accuracy = accuracy_score(y_test, predictions)

print(f"Test Set Accuracy: {accuracy:.4f}")A reasonably high test set accuracy suggests our code/model is working correctly.

Training via SageMaker (using notebook as controller) - custom train.py script

Unlike “local” training (using this notebook), this next approach leverages SageMaker’s managed infrastructure to handle resources, parallelism, and scalability. By specifying instance parameters, such as instance_count and instance_type, you can control the resources allocated for training.

Which instance to start with?

In this example, we start with one ml.m5.large instance, which is suitable for small- to medium-sized datasets and simpler models. Using a single instance is often cost-effective and sufficient for initial testing, allowing for straightforward scaling up to more powerful instance types or multiple instances if training takes too long. See here for further guidance on selecting an appropriate instance for your data/model: EC2 Instances for ML

Overview of Estimator classes in SageMaker

To launch this training “job”, we’ll use the XGBoost “Estimator. In

SageMaker, Estimator classes streamline the configuration and training

of models on managed instances. Each Estimator can work with custom

scripts and be enhanced with additional dependencies by specifying a

requirements.txt file, which is automatically installed at

the start of training. Here’s a breakdown of some commonly used

Estimator classes in SageMaker:

1. Estimator (Base Class)

- Purpose: General-purpose for custom Docker containers or defining an image URI directly.

-

Configuration: Requires specifying an

image_uriand custom entry points. -

Dependencies: You can use

requirements.txtto install Python packages or configure a custom Docker container with pre-baked dependencies. - Ideal Use Cases: Custom algorithms or models that need tailored environments not covered by built-in containers.

2. XGBoost Estimator

- Purpose: Provides an optimized container specifically for XGBoost models.

-

Configuration:

-

entry_point: Path to a custom script, useful for additional preprocessing or unique training workflows. -

framework_version: Select XGBoost version, e.g.,"1.5-1". -

dependencies: Specify additional packages throughrequirements.txtto enhance preprocessing capabilities or incorporate auxiliary libraries.

-

- Ideal Use Cases: Tabular data modeling using gradient-boosted trees; cases requiring custom preprocessing or tuning logic.

3. PyTorch Estimator

- Purpose: Configures training jobs with PyTorch for deep learning tasks.

-

Configuration:

-

entry_point: Training script with model architecture and training loop. -

instance_type: e.g.,ml.p3.2xlargefor GPU acceleration. -

framework_versionandpy_version: Define specific versions. -

dependencies: Install any required packages viarequirements.txtto support advanced data processing, data augmentation, or custom layer implementations.

-

- Ideal Use Cases: Deep learning models, particularly complex networks requiring GPUs and custom layers.

4. SKLearn Estimator

- Purpose: Supports scikit-learn workflows for data preprocessing and classical machine learning.

-

Configuration:

-

entry_point: Python script to handle feature engineering, preprocessing, or training. -

framework_version: Version of scikit-learn, e.g.,"1.0-1". -

dependencies: Userequirements.txtto install any additional Python packages required by the training script.

-

- Ideal Use Cases: Classical ML workflows, extensive preprocessing, or cases where additional libraries (e.g., pandas, numpy) are essential.

5. TensorFlow Estimator

- Purpose: Designed for training and deploying TensorFlow models.

-

Configuration:

-

entry_point: Script for model definition and training process. -

instance_type: Select based on dataset size and computational needs. -

dependencies: Additional dependencies can be listed inrequirements.txtto install TensorFlow add-ons, custom layers, or preprocessing libraries.

-

- Ideal Use Cases: NLP, computer vision, and transfer learning applications in TensorFlow.

6. HuggingFace Estimator

-

Purpose: Provides managed containers for running

inference, fine-tuning, and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

workflows using the Hugging Face

transformerslibrary.

-

Configuration:

-

entry_point: Custom script for training or inference (e.g.,train.pyorrag_inference.py).

-

transformers_version,pytorch_version,py_version: Define framework versions.

-

dependencies: Optionalrequirements.txtfor extra libraries.

-

- Ideal Use Cases: RAG pipelines, LLM inference, NLP, vision, or multimodal tasks using pretrained Transformer models.

Configuring custom environments with

requirements.txt

For all these Estimators, adding a requirements.txt file

as a dependencies argument ensures that additional packages

are installed before training begins. This approach allows the use of

specific libraries that may be critical for custom preprocessing,

feature engineering, or model modifications. Here’s how to include

it:

PYTHON

# # Customizing estimator using requirements.txt

# from sagemaker.sklearn.estimator import SKLearn

# sklearn_estimator = SKLearn(

# base_job_name=notebook_instance_name,

# entry_point="train_script.py",

# role=role,

# instance_count=1,

# instance_type="ml.m5.large",

# output_path=f"s3://{bucket_name}/output",

# framework_version="1.0-1",

# dependencies=['requirements.txt'], # Adding custom dependencies

# hyperparameters={

# "max_depth": 5,

# "eta": 0.1,

# "subsample": 0.8,

# "num_round": 100

# }

# )This setup simplifies training, allowing you to maintain custom environments directly within SageMaker’s managed containers, without needing to build and manage your own Docker images. The AWS SageMaker Documentation provides lists of pre-built container images for each framework and their standard libraries, including details on pre-installed packages.

Deploying to other instances

For this deployment, we configure the “XGBoost” estimator with a custom training script, train_xgboost.py, and define hyperparameters directly within the SageMaker setup. Here’s the full code, with some additional explanation following the code.

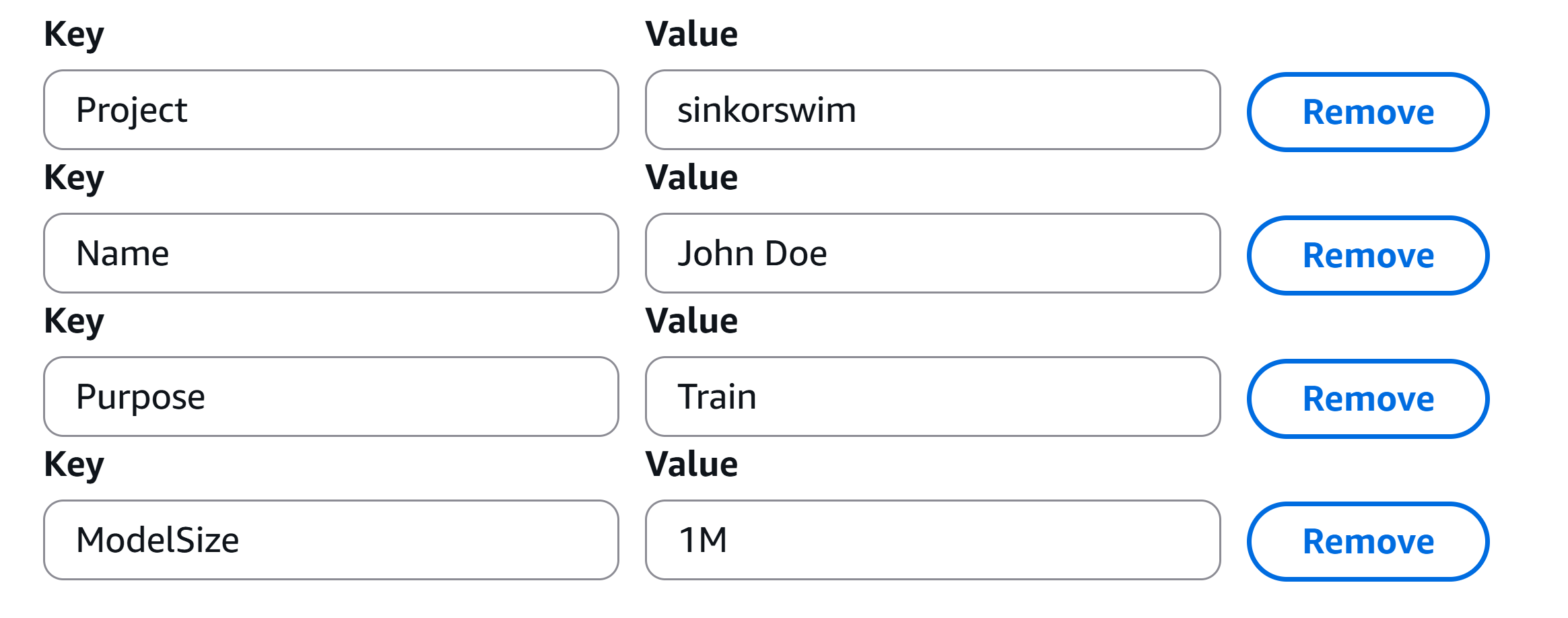

Cost tracking

When you launch a SageMaker training job from a notebook, SageMaker creates new managed resources (EC2 instances, attached storage, logs) on your behalf. These resources do not automatically inherit the notebook instance’s tags.

To avoid this, we explicitly tag each training job at launch time. This ensures that compute usage is traceable to a project, a purpose, and a human-readable name, even after the job has completed.

PYTHON

name = "John Doe" # replace with your name

project = "sinkorswim" # replace with your team name

purpose = "train_XGBoost"

job_tags = [

{"Key": "Name", "Value": name},

{"Key": "Project", "Value": project},

{"Key": "Purpose", "Value": purpose},

]PYTHON

from sagemaker.inputs import TrainingInput

from sagemaker.xgboost.estimator import XGBoost

# Define instance type/count we'll use for training

instance_type="ml.m5.large"