Data and Metadata

Last updated on 2023-11-16 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is data and what is metadata?

- Which types of metadata exist?

- Where can I find (meta)data in everyday examples?

- What are bad and good enough practices of metadata handling in the scientific context?

Objectives

- Recognize and describe examples of (meta)data

- Name best and worst practice situations in research (meta)data handling

- Getting familiar with the example dataset

Data – Information – Knowledge – Wisdom

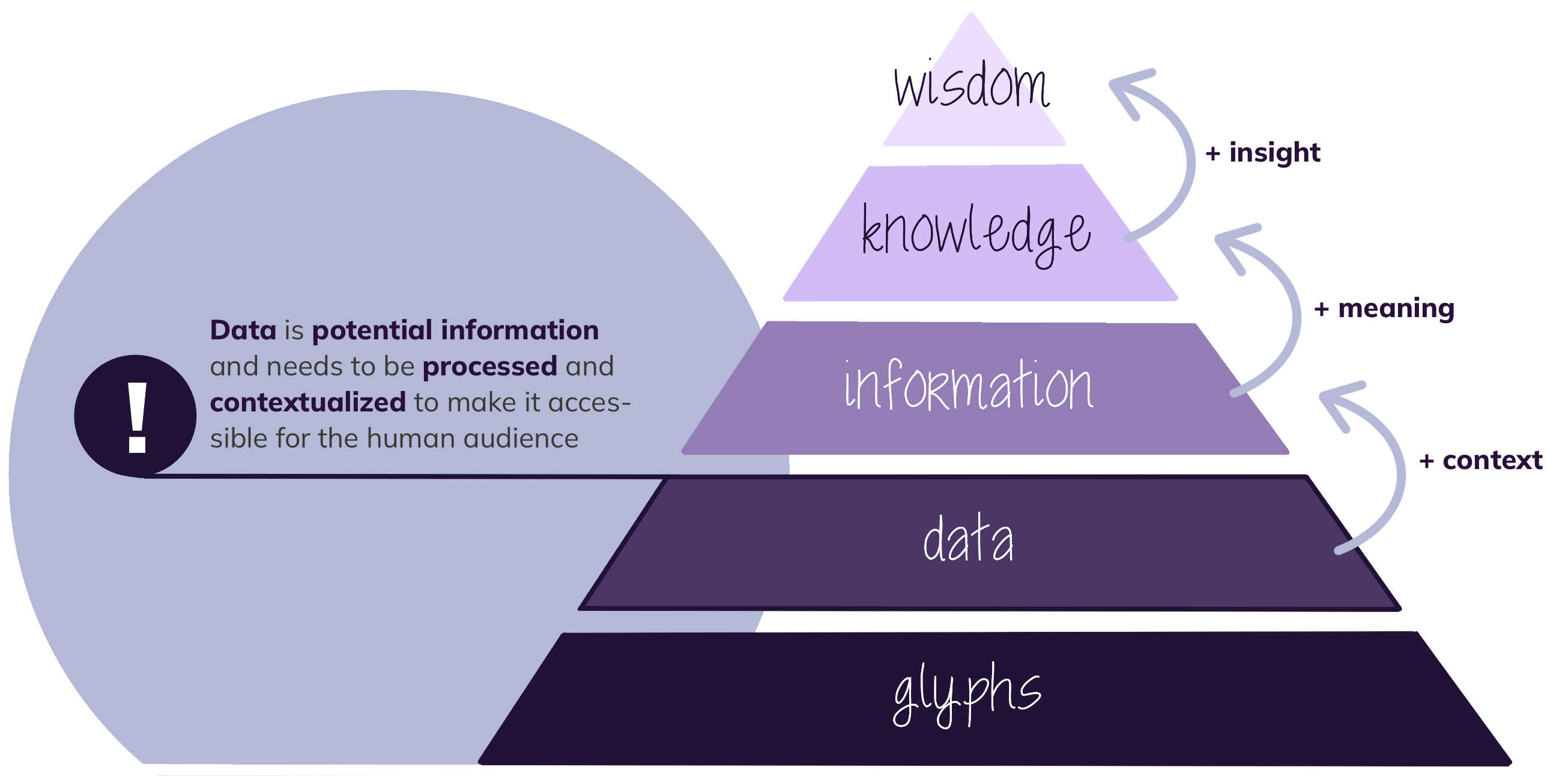

The question “What is data?” seems trivial at first, but if we look at the definition, it is apparent that the question is not that easy to answer. In information science, we distinguish between Glyphs (or symbols), data, information, knowledge and wisdom. GLYPHS are the smallest unit of data representation. Glyphs represent the symbols of which data can be composed.

To cite the information scientist Jeffrey Pomerantz, “DATA is stuff. It is raw, unprocessed, possibly even untouched by human hands, unviewed by human eyes, un-thought-about by human minds”1. In other words, data is potential information, that requires processing and context to extract the information held within.

Accordingly, INFORMATION is processed, human-consumable data. If this information is internalized by a human being, it is called KNOWLEDGE. This knowledge can be applied in a broader context by the human being. Applied knowledge is called WISDOM. The key to reaching wisdom from data is processing and contextualizing data to extract information. To achieve this goal we often need to add a description to the data: metadata.

Information pyramid

Metadata

Metadata is (semi-)structured data that provides information about characteristics of other (more complex) data objects (e.g. files or documents). Regarding research data, metadata gives the observer the necessary context to interpret the data and derive information from it. Although metadata is data itself, it only is meaningful in connection with a data object that is described by the metadata record (e.g. the meta-information in a book about said book). Metadata can be found inside of a data object (e.g. in a book, in a data record) or as a separate object (e.g. library catalogue, separate file).

National Information Standards Organization (NISO, 2004, from “Big Data, Little Data, No Data”, Christine L. Borgman, 2015): “Metadata is structured information that describes, explains, locates, or otherwise makes it easier to retrieve, use or manage an information resource”.

Types of Metadata

Descriptive metadata provides information about the intellectual content of a (digital) object (e.g. title, author, date of publication, subject, description, unique identifier). 2

Administrative metadata provides information to support the management of a resource (e.g. technical information regarding the file’s creation and format, version, information about copyright, licence and intellectual property rights). 2

Structural metadata specifies the relationships between components of a (digital) object and between different (digital) objects (e.g. chapters in a book). 2

Challenge 1: Real-world metadata

- Open one of these web pages in your preferred browser:

- Open one of the articles linked on the main page.

- Inspect the web page source code.

| Browser | Shortcut to Source Code |

|---|---|

| Firefox | Ctrl + u |

| Chrome | Ctrl + u |

| Safari | Option + Command + u |

| Opera | Ctrl + u |

| Edge | Ctrl + u |

| Internet Explorer | Ctrl + u |

- Look for meta

tags in the HTML source code

<head>element. - Assign some

<meta>tags to one of the categories descriptive, administrative, structural

Metadata records

Handwritten (lab) notes Handwritten (lab) notes are still a common practice in many scientific disciplines. These notes are easy to take during data generation. The greatest disadvantage, however, is the physical separation from the data itself and the difficulty to find, store and share this information. Often, handwritten lab notes do not follow a predictable structure and, hence, are hard to interpret and sometimes even hard to read.

Readme style text documents Recording your metadata

(additionally) in a digital README-style text document

comes with one great advantage: the metadata can be associated and

stored directly with the experimental data. README-style

metadata best practices include:3

- creating one

READMEfile for each data file, whenever possible. - naming the

READMEin a way that it is easily associated with the data file(s) it describes. - writing the

READMEdocument as a plain text file avoids proprietary data formats. - structuring multiple

READMEfiles identically. - where possible follow established conventions for scientific vocabulary (i.e. from glossaries or resources such as the IUPAC Gold book)

We strongly recommend to use this

template for README-style metadata

documents.4

Key Points

- Data is potential information.

- The boundaries between data and metadata are blurred and depend on the context.

-

Scientific meta information is often recorded in

handwritten (lab) notes. A better - though still limited - solution, is

the documentation of scientific metadata in accompanying

READMEfiles

Pomerantz, J. (2015). Metadata. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10237.001.0001↩︎

Zhang, A. B., Gourley, D. (2008). Metadata strategy in Creating Digital Collections: a practical Guide. Sawston, UK: Woodhead Publishing.↩︎

Chadwick, I. (2016). Research Data Management: guide to writing ”readme” type metadata. The Open University. https://www.open.ac.uk/library-research-support/sites/www.open.ac.uk.library-research-support/files/files/RDM-Guidelines-for-creating-readme-style-metadata.pdf↩︎

Guide to writing “readme” style metadata – Cornell Data Services. (n.d.). https://data.research.cornell.edu/data-management/sharing/readme/↩︎