Evaluate a Convolutional Neural Network and Make Predictions (Classifications)

Last updated on 2024-05-24 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How do you use a model to make a prediction?

- How do you measure model prediction accuracy?

- What can you do to improve model performance?

- What is a hyperparameter?

Objectives

- Use a convolutional neural network (CNN) to make a prediction (i.e. classify an image).

- Explain how to measure the performance of a CNN.

- Know what steps to take to improve model accuracy.

- Explain hyperparameter tuning.

- Be familiar with advantages and disadvantages of different optimizers.

Step 7. Perform a Prediction/Classification

After you fully train the network to a satisfactory performance on the training and validation sets, we use it to perform predictions on a special hold-out set, the test set. The prediction accuracy of the model on new images will be used in Step 8. Measuring performance to measure the performance of the network.

Prepare test dataset

Recall in Episode 02 Introduction to

Image Data we discussed how to split your data into training and

test datasets and why. In most cases, that means you already have a test

set on hand. For example, we are using

keras.models.load_model to create a training and test

set.

When creating and using a test set there are a few things to check:

- It only contains images the model has never seen before.

- It is sufficiently large to provide a meaningful evaluation of model performance.

- It should include images from every target label plus images of classes not in your target set.

- It is processed in the same way as your training set.

Check to make sure you have a model in memory and a test dataset:

PYTHON

# load the CIFAR-10 dataset included with the keras library

(train_images, train_labels), (test_images, test_labels) = keras.datasets.cifar10.load_data()

# create a list of classnames

class_names = ['airplane', 'automobile', 'bird', 'cat', 'deer', 'dog', 'frog', 'horse', 'ship', 'truck']

# normalize the RGB values to be between 0 and 1

test_images = test_images / 255.0

# check test image dataset is loaded - images and labels

print('Test: Images=%s, Labels=%s' % (test_images.shape, test_labels.shape))OUTPUT

Test: Images=(10000, 32, 32, 3), Labels=(10000, 1)CHALLENGE How big should our test data set be?

It depends! Recall in an Episode 02 Introduction to Image Data Callout we talked about the different ways to partition the data into training, validation and test data sets. For example, using the Stratified Sampling technique, we might split the data using these rations: 80-10-10 or 70-15-15.

The test set should be sufficiently large to provide a meaningful evaluation of your model’s performance. Smaller datasets might not provide a reliable estimate of how well your model generalizes.

Predict

Armed with a test dataset, we will choose our best performing CNN and use it to predict the class labels.

The Keras method to predict is found in the Model training APIs section of the documentation and has the following definition:

Model.predict(x, batch_size=None, verbose="auto", steps=None, callbacks=None)- x refers to the input samples which in our case is an array of images

CHALLENGE Write the code to make classname predictions on test data

Use the Model.predict function to predict the classnames

of your test data.

Hint 1: If not already in memory, use ‘keras.models.load_model()’

Hint 2: Capture the output of the predict method in a variable named ‘predictions’.

Question: What did the predict method return?

PYTHON

# load preferred model

model_best = keras.models.load_model('fit_outputs/model_dropout.keras')

print('We are using', model_best.name)

# use preferred model to predict

predictions = model_best.predict(x=test_images)

print(predictions)OUTPUT

We are using cifar_model_dropout

313/313 [==============================] - 1s 3ms/step

[[2.5438464e-03 2.8599051e-04 1.8983794e-02 ... 1.2449322e-03 2.1590138e-02 1.1813908e-03]

[1.4163133e-02 3.0712727e-01 6.2913182e-06 ... 7.1710346e-08 6.7631084e-01 2.3808377e-03]

[3.7576403e-02 3.7346989e-01 2.7308019e-04 ... 2.1147232e-04 4.7246802e-01 1.1511791e-01]

...

[3.6926474e-05 2.6195229e-07 4.9670707e-02 ... 5.6971662e-02 7.5488140e-05 1.2449813e-05]

[2.7443832e-02 3.4728521e-01 4.3887336e-02 ... 1.0875220e-01 1.4605661e-03 1.1823817e-02]

[6.4299519e-07 1.0424572e-05 6.5142207e-04 ... 9.7329682e-01 4.3226078e-07 5.3953562e-07]]Recall our model will return a vector of probabilities, one for each class. By finding the class with the highest probability, we can select the most likely class name of the object. We will use numpy.argmax() to find the class with the highest probability in each row.

PYTHON

# convert probability predictions to table using class names for column names

prediction_df = pd.DataFrame(data=predictions, columns=class_names)

# inspect

print(prediction_df.head())

# convert predictions to class labels

predicted_labels = np.argmax(a=predictions, axis=1)

print(predicted_labels)OUTPUT

We are using cifar_model_dropout

airplane automobile bird ... horse ship truck

0 0.165748 -0.118394 0.062156 ... 0.215477 0.013811 -0.047446

1 0.213530 -0.126139 0.052813 ... 0.264517 0.009097 -0.091710

2 0.211900 -0.099055 0.047890 ... 0.242345 -0.014492 -0.073153

3 0.187883 -0.085144 0.044609 ... 0.217864 0.007502 -0.055209

4 0.190110 -0.118892 0.054869 ... 0.252434 -0.030064 -0.061485

[5 rows x 10 columns]

Out [5]: array([3, 8, 8, ..., 5, 1, 7], dtype=int64)Step 8. Measuring performance

After using our preferred model to make predictions on a test dataset of unseen images we want to know how well it performed. There are many different methods available for measuring performance and which one to use depends on the type of task we are attempting.

A quick and easy way to check the accuracy of our model is to use the

accuracy_score() from sklearn.metrics. This

function takes as a first parameter the true labels of the test set. The

second parameter is the predicted labels from our model.

PYTHON

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

# evaluate the model on the test data set

test_acc = accuracy_score(y_true=test_labels, y_pred=predicted_labels)

print('Accuracy:', round(test_acc,2))OUTPUT

Accuracy: 0.67To understand a bit more about how this accuracy is obtained, we can create a confusion matrix.

Confusion matrix

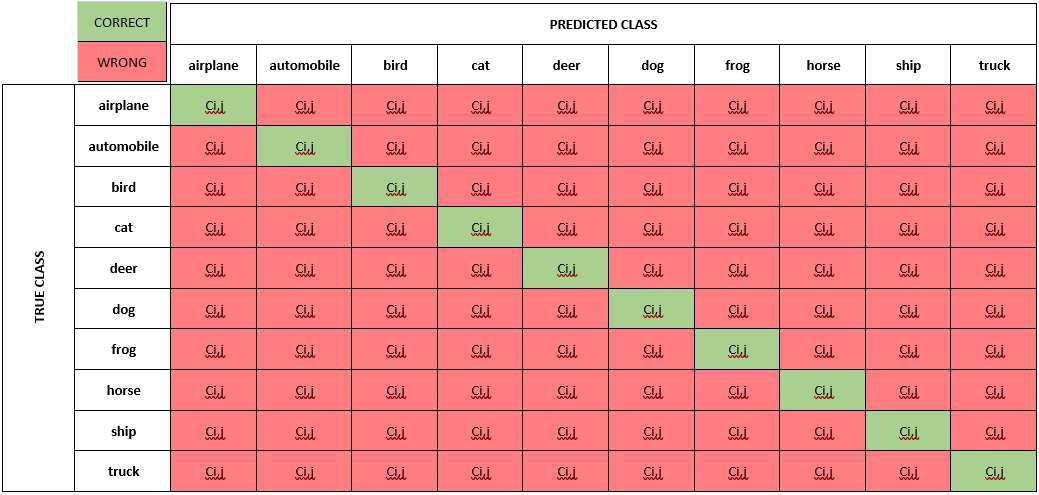

In the case of multiclass classifications, each cell value (Ci,j) is equal to the number of observations known to be in group i and predicted to be in group j. The diagonal cells in the matrix are where the true class and predicted class match.

To create a confusion matrix in python, we use another convenient

function from sklearn.metrics called

confusion_matrix. This function takes the same two

parameters we just used, the true labels and the predicted labels.

PYTHON

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix

# create a confusion matrix

conf_matrix = confusion_matrix(y_true=test_labels, y_pred=predicted_labels)

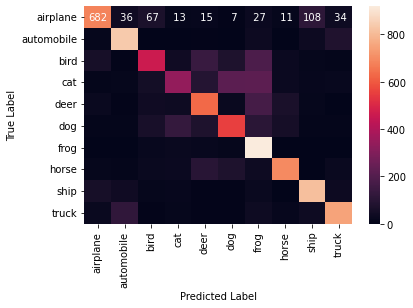

print(conf_matrix)OUTPUT

[[682 36 67 13 15 7 27 11 108 34]

[ 12 837 3 2 6 3 32 0 29 76]

[ 56 4 462 37 137 72 184 26 13 9]

[ 10 13 48 341 87 217 221 27 17 19]

[ 23 4 38 34 631 23 168 63 13 3]

[ 8 9 59 127 74 550 103 51 10 9]

[ 3 3 18 23 18 12 919 2 1 1]

[ 14 8 24 28 98 75 34 693 2 24]

[ 56 39 11 17 4 6 22 2 813 30]

[ 23 118 6 12 6 5 33 15 35 747]]Unfortunately, this matrix is hard to read. It’s not clear which column and which row correspond to which class. We can convert the matrix to a pandas dataframe using the class labels for its index (rows) and columns.

PYTHON

# Convert confustion matrix to a pandas dataframe

confusion_df = pd.DataFrame(data=conf_matrix, index=class_names, columns=class_names)

# Set the names of the x and y axis, this helps with the readability of the heatmap

confusion_df.index.name = 'True Label'

confusion_df.columns.name = 'Predicted Label'We can then use the heatmap function from seaborn to create a nice

visualization of the confusion matrix.

- The

annot=Trueparameter here will put the numbers from the confusion matrix in the heatmap. - The

fmt=3gwill display the values with three significant digits.

CHALLENGE Confusion Matrix

Measure the performance of the neural network you trained and visualized as a confusion matrix.

Q1. Did the neural network perform well on the test set?

Q2. Did you expect this from the training loss plot?

Q3. What could we do to improve the performance?

A1. The confusion matrix illustrates that the predictions are not bad but can be improved.

A2. I expected the performance to be better than average because the accuracy of the model I chose was 67 per cent on the validation set.

A3. We can try many things to improve the performance from here. One of the first things we can try is to change the network architecture. However, in the interest of time, and given we already learned how to build a CNN, we will now change the training parameters.

Step 9. Tune hyperparameters

Recall the following from Episode 01 Introduction to Deep Learning:

What are hyperparameters?

Hyperparameters are the parameters set by the person configuring the model instead of those learned by the algorithm itself. Like the dials on a radio which are tuned to the best frequency, hyperparameters can be tuned to the best combination for a given model and context.

These hyperparameters can include the learning rate, the number of layers in the network, the number of neurons per layer, and many more. The tuning process is systematic searching for the best combination of hyperparameters to optimize the model’s performance.

In some cases, it might be necessary to adjust these and re-run the training many times before we are happy with the result.

Table 1. List of some of the hyperparameters to tune and when.

| During Build | When Compiling | During Training |

|---|---|---|

| number of neurons | loss function | epoch |

| activation function | optimizer | batch size |

| dropout rate | learning rate |

There are a number of techniques used to tune hyperparameters. Let us explore a few of them.

One common method for hyperparameter tuning is by using a

for loop to change a particular parameter.

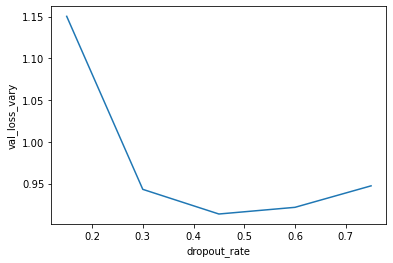

CHALLENGE Tune Dropout Rate (Model Build) using a For Loop

Q1. What do you think would happen if you lower the dropout rate? Write some code to vary the dropout rate and investigate how it affects the model training.

SH

Hint 1: Modify the 'create_model_dropout()' function and define a `create_model_dropout_vary` function that has `dropout_rate` as its only parameter.

Hint 2: Use a for loop to call your function with varying dropout ratesQ2. You are varying the dropout rate and checking its effect on the model performance, what is the term associated to this procedure?

A1. Varying the dropout rate

The code below instantiates and trains a model with varying dropout rates. The resulting plot indicates the ideal dropout rate in this case is around 0.45. This is where the validation loss is lowest.

SH

NB1: It takes a while to train these five networks.

NB2: You should do this with a test set and not with the validation set!PYTHON

# define new dropout function that accepts a dropout rate

def create_model_dropout_vary(dropout_rate):

# Input layer of 32x32 images with three channels (RGB)

inputs_vary = keras.Input(shape=train_images.shape[1:])

# CNN Part 2

# Convolutional layer with 16 filters, 3x3 kernel size, and ReLU activation

x_vary = keras.layers.Conv2D(filters=16, kernel_size=(3,3), activation='relu')(inputs_vary)

# Pooling layer with input window sized 2x2

x_vary = keras.layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2,2))(x_vary)

# Second Convolutional layer with 32 filters, 3x3 kernel size, and ReLU activation

x_vary = keras.layers.Conv2D(filters=32, kernel_size=(3,3), activation='relu')(x_vary)

# Second Pooling layer with input window sized 2x2

x_vary = keras.layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2,2))(x_vary)

# Second Convolutional layer with 64 filters, 3x3 kernel size, and ReLU activation

x_vary = keras.layers.Conv2D(filters=64, kernel_size=(3,3), activation='relu')(x_vary)

# Dropout layer randomly drops x% of the input units

x_vary = keras.layers.Dropout(rate=dropout_rate)(x_vary) # This is new!

# Flatten layer to convert 2D feature maps into a 1D vector

x_vary = keras.layers.Flatten()(x_vary)

# CNN Part 3

# Output layer with 10 units (one for each class) and softmax activation

outputs_vary = keras.layers.Dense(units=10, activation='softmax')(x_vary)

model_vary = keras.Model(inputs = inputs_vary,

outputs = outputs_vary,

name ="cifar_model_dropout_vary")

return model_vary

# specify range of dropout rates

dropout_rates = [0.15, 0.3, 0.45, 0.6, 0.75]

# create empty list to hold losses

val_losses_vary = []

# use for loop to explore varying the dropout rate

for dropout_rate in dropout_rates:

# create the model

model_vary = create_model_dropout_vary(dropout_rate)

# compile the model

model_vary.compile(optimizer = keras.optimizers.Adam(),

loss = keras.losses.CategoricalCrossentropy(),

metrics = keras.metrics.CategoricalAccuracy())

# fit the model

model_vary.fit(x = train_images, y = train_labels,

batch_size = 32,

epochs = 10,

validation_data = (val_images, val_labels)))

# evaluate the model on the test data set

val_loss_vary, val_acc_vary = model_vary.evaluate(val_images, val_labels)

# save the evaulation metrics

val_losses_vary.append(val_loss_vary)

# convert rates and metrics to dataframe for plotting

loss_df = pd.DataFrame({'dropout_rate': dropout_rates, 'val_loss_vary': val_losses_vary})

# plot the loss and accuracy from the training process

sns.lineplot(data=loss_df, x='dropout_rate', y='val_loss_vary')

A2. Term associated to this procedure

Another common method for hyperparameter tuning is grid search.

What is Grid Search?

Grid Search or GridSearchCV (as per the library function

call) is foundation method for hyperparameter tuning. The aim of

hyperparameter tuning is to define a grid of possible values for each

hyperparameter you want to tune. GridSearch will then evaluate the model

performance for each combination of hyperparameters in a brute-force

manner, iterating through every possible combination in the grid.

For instance, suppose you’re tuning two hyperparameters:

Learning rate: with possible values [0.01, 0.1, 1]

Batch size: with possible values [10, 50, 100]

GridSearch will evaluate the model for all 3*3 = 9 combinations (e.g., {0.01, 10}, {0.01, 50}, {0.1, 10}, and so on).

CHALLENGE Tune Optimizer using Grid Search

In Episode 04 Compile and Train a

Convolutional Neural Network we talked briefly about the

Adam optimizer used in our Model.compile

discussion. Recall the optimizer refers to the

algorithm with which the model learns to optimize on the provided loss

function.

Write some code to demonstrate how GridSearch works.

Hint 1: Use the create_model_intro() definition as the

build function to use during GridSearch and modify it

to include the ‘Model.compile’ method call.

PYTHON

# use the intro model for gridsearch and add compile method call

def create_model_intro():

# CNN Part 1

# Input layer of 32x32 images with three channels (RGB)

inputs_intro = keras.Input(shape=train_images.shape[1:])

# CNN Part 2

# Convolutional layer with 16 filters, 3x3 kernel size, and ReLU activation

x_intro = keras.layers.Conv2D(filters=16, kernel_size=(3,3), activation='relu')(inputs_intro)

# Pooling layer with input window sized 2x2

x_intro = keras.layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2,2))(x_intro)

# Second Convolutional layer with 32 filters, 3x3 kernel size, and ReLU activation

x_intro = keras.layers.Conv2D(filters=32, kernel_size=(3,3), activation='relu')(x_intro)

# Second Pooling layer with input window sized 2x2

x_intro = keras.layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2,2))(x_intro)

# Flatten layer to convert 2D feature maps into a 1D vector

x_intro = keras.layers.Flatten()(x_intro)

# Dense layer with 64 neurons and ReLU activation

x_intro = keras.layers.Dense(units=64, activation='relu')(x_intro)

# CNN Part 3

# Output layer with 10 units (one for each class) and softmax activation

outputs_intro = keras.layers.Dense(units=10, activation='softmax')(x_intro)

# create the model

model_intro = keras.Model(inputs = inputs_intro,

outputs = outputs_intro,

name = "cifar_model_intro")

# compile the model

model_intro.compile(optimizer = keras.optimizers.Adam(),

loss = keras.losses.CategoricalCrossentropy(),

metrics = keras.metrics.CategoricalAccuracy())

return model_introSecondly, we can define our GridSearch parameters and assign fit results to a variable for output.

PYTHON

from scikeras.wrappers import KerasClassifier

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

# Instantiate wrapper class for GridSearchCV

model = KerasClassifier(build_fn=create_model_intro, epochs=2, batch_size=32, verbose=0) # epochs, batch_size, verbose can be adjusted as required. Using low epochs to save computation time and demonstration purposes only

# Define the grid search parameters

optimizer = ['SGD', 'RMSprop', 'Adam']

param_grid = dict(optimizer=optimizer)

# search over specified parameter values for an estimator

grid = GridSearchCV(estimator=model, param_grid=param_grid, n_jobs=1, cv=3)

# run fit with all parameters

grid_result = grid.fit(train_images, train_labels)

# Summarize results

print("Best: %f using %s" % (grid_result.best_score_, grid_result.best_params_))OUTPUT

Best: 0.586660 using {'optimizer': 'RMSprop'}Thus, we can interpret from this output that our best tested optimiser is the root mean square propagation optimiser, or RMSprop.

Curious about RMSprop? RMSprop in Keras and RMSProp, Cornell University

Here is a third example of tuning hyperparameters, this time using a for loop to tune the activation function.

Activation Functions

In Episode 03 Build a Convolutional

Neural Network we talked briefly about the relu

activation function passed as an argument to our Conv2D

hidden layers.

An activation function is like a switch, or a filter, that we use in artificial neural networks, inspired by how our brains work. These functions play a crucial role in determining whether a neuron (a small unit in the neural network) should “fire” or become active.

Think of an activation function as a tiny decision-maker for each neuron in a neural network. It helps determine whether the neuron should ‘fire’, or pass on information, or stay ‘off’ and remain silent, much like a light switch controls whether the light should be ON or OFF. Activation functions are crucial because they add non-linearity to the neural network. Without them, the network would be like a simple linear model, unable to learn complex patterns in data.

How do you know what activation function to choose?

Neural networks can be tuned to leverage many different types of activation functions. In fact, it is a crucial decision as the choice of activation function will have a direct impact on the performance of the model.

Table 2. Description of each activation function, its benefits, and drawbacks.

| Activation Function | Positives | Negatives |

|---|---|---|

| ReLU | - Addresses vanishing gradient problem - Computationally efficient |

- Can cause “dying neurons” - Not zero-centered |

| Leaky ReLU | - Addresses the “dying ReLU” problem - Computationally efficient |

- Empirical results can be inconsistent - Not zero-centered |

| Sigmoid | - Outputs between 0 and 1 - Smooth gradient |

- Can cause vanishing gradient problem - Computationally more expensive |

| Tanh | - Outputs between -1 and 1 - Zero-centered |

- Can still suffer from vanishing gradients to some extent |

| Softmax | - Used for multi-class classification - Outputs a probability distribution |

- Used only in the output layer for classification tasks |

| SELU | - Self-normalizing properties - Can outperform ReLU in deeper networks |

- Requires specific weight initialization - May not perform well outside of deep architectures |

CHALLENGE Tune Activation Function using For Loop

Write some code to assess activation function performance.

Hint 1: Use the create_model_intro() definition as the

build function to use during GridSearch. Make

modifications to take a single parameter ‘activation_function and this

time include the ’Model.compile’ method call in the definition.

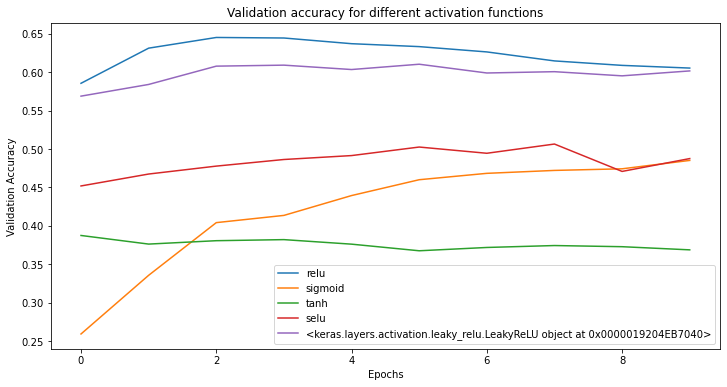

The code below serves as a practical means for exploring activation performance on an image dataset.

PYTHON

# modify the intro model to sample activation functions

def create_model_act(activation_function):

# CNN Part 1

# Input layer of 32x32 images with three channels (RGB)

inputs_act = keras.Input(shape=train_images.shape[1:])

# CNN Part 2

# Convolutional layer with 16 filters, 3x3 kernel size, and ReLU activation

x_act = keras.layers.Conv2D(filters=16, kernel_size=(3,3), activation=activation_function)(inputs_act)

# Pooling layer with input window sized 2x2

x_act = keras.layers.MaxPooling2D((2, 2))(x_act)

# Second Convolutional layer with 32 filters, 3x3 kernel size, and ReLU activation

x_act = keras.layers.Conv2D(filters=32, kernel_size=(3,3), activation=activation_function)(x_act)

# Second Pooling layer with input window sized 2x2

x_act = keras.layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2,2))(x_act)

# Flatten layer to convert 2D feature maps into a 1D vector

x_act = keras.layers.Flatten()(x_act)

# Dense layer with 64 neurons and ReLU activation

x_act = keras.layers.Dense(units=64, activation=activation_function)(x_act)

# CNN Part 3

# Output layer with 10 units (one for each class) and softmax activation

outputs_act = keras.layers.Dense(units=10, activation='softmax')(x_act)

# create the model

model_act = keras.Model(inputs = inputs_act,

outputs = outputs_act,

name="cifar_model_activation")

# compile the model

model_act.compile(optimizer = keras.optimizers.Adam(),

loss = keras.losses.CategoricalCrossentropy(),

metrics = keras.metrics.CategoricalAccuracy())

return model_act

# create a ist of activation functions to try

activations = ['relu', 'sigmoid', 'tanh', 'selu', keras.layers.LeakyReLU()]

# create a dictionary object to store the training history

history_data = {}

# train the model with each activation function and store the history

for activation in activations:

model = create_model(activation)

history = model.fit(x = train_images, y = train_labels,

batch_size = 32,

epochs = 10,

validation_data = (val_images, val_labels))

# plot the validation accuracy for each activation function

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 6))

for activation, history in history_data.items():

plt.plot(history.history['val_categorical_accuracy'], label=activation)

plt.title('Validation accuracy for different activation functions')

plt.xlabel('Epochs')

plt.ylabel('Validation Accuracy')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

In this figure, after 10 epochs, the ReLU and

Leaky ReLU activation functions appear to converge around

0.60 per cent validation accuracy. We recommend when tuning your model

to ensure you use enough epochs to be confident in your results.

CHALLENGE What could be next steps to further improve the model?

With unlimited options to modify the model architecture or to play with the training parameters, deep learning can trigger very extensive hunting for better and better results. Usually models are “well behaving” in the sense that small chances to the architectures also only result in small changes of the performance (if any). It is often tempting to hunt for some magical settings that will lead to much better results. But do those settings exist? Applying common sense is often a good first step to make a guess of how much better could results be.

- What changes to the model architecture might make sense to explore?

- Ignoring changes to the model architecture, what might notably improve the prediction quality?

This is an open question.

Regarding the model architecture:

- In the present case we do not see a magical silver bullet to suddenly boost the performance. But it might be worth testing if deeper networks do better (more layers).

Other changes that might impact the quality notably:

- The most obvious answer here would be: more data! Even this will not always work (e.g., if data is very noisy and uncorrelated, more data might not add much).

- Related to more data: use data augmentation. By creating realistic variations of the available data, the model might improve as well.

- More data can mean more data points and also more features!

By now you should have a well-trained, finely-tuned model that makes accurate predictions and are ready to share the model with others.

- Model accuracy must be measured on a test dataset with images your model has not seen before.

- Use Model.predict() to make a prediction with your model.

- There are many hyperparameters to choose from to improve model performance.

- Fitting separate models with different hyperparameters and comparing their performance is a common and good practice in deep learning.