Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average Forecasts

Last updated on 2023-08-20 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How do we account for seasonal processes in time-series forecasting?

Objectives

- Explain the SARIMA(p,d, q)(P, D, Q)m model.

Introduction

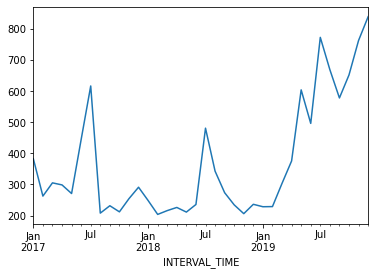

The data we have been using so far have apparent seasonal trends. That is, in addition to trends across the entire dataset, there are periodic trends. We can see this most clearly if we look at a plot of monthly power consumption from a single meter over three years, 2017-2019.

PYTHON

d = pd.read_csv("../../data/ladpu_smart_meter_data_01.csv")

d.set_index(pd.to_datetime(d["INTERVAL_TIME"]), inplace=True)

d.sort_index(inplace=True)

d.resample("M")["INTERVAL_READ"].sum().plot()

The above plot shows an overall trend of decreased power usage between 2017 and 2018, with a significant increase in power usage in 2019. What may stand out more prominently, however, are the seasonal trends in the data. In particular, there are annual peaks in power consumption in the summer, with smaller peaks in the winter. Power consumption in spring and fall is comparatively low.

Though our example here is explicitly seasonal, seasonal trends can be any periodic trend, including monthly, weekly, or daily trends. In fact, it is possible for a time-series to exhibit multiple trends. This is true of our data. Consider your own power consumption at home, where periodic trends can include

- Daily trends where power consumption may be greater in the morning and evening, before and after work and before sleep.

- Weekly trends where power consumption may be greater over the weekend, or outside of whatever your normal work hours may be.

In this episode, we will expand our model to account for periodic or seasonal trends in the time-series.

About the code

The code used in this lesson is based on and, in some cases, a direct application of code used in the Manning Publications title, Time series forecasting in Python, by Marco Peixeiro.

Peixeiro, Marco. Time Series Forecasting in Python. [First edition]. Manning Publications Co., 2022.

The original code from the book is made available under an Apache 2.0 license. Use and application of the code in these materials is within the license terms, although this lesson itself is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 license. Any further use or adaptation of these materials should cite the source code developed by Peixeiro:

Peixeiro, Marco. Timeseries Forecasting in Python [Software code]. 2022. Accessed from https://github.com/marcopeix/TimeSeriesForecastingInPython.

Create the data subset

For this episode, we return to the data subset we’ve used for all but the last episode, with the difference that we will limit the date range of the subset to January - June, 2019.

First, load the necessary libaries and define the function to read, subset, and resample the data.

PYTHON

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error, mean_absolute_error

from statsmodels.tsa.seasonal import STL

from statsmodels.stats.diagnostic import acorr_ljungbox

from statsmodels.tsa.statespace.sarimax import SARIMAX

from statsmodels.tsa.stattools import adfuller

from tqdm import tqdm_notebook

from itertools import product

from typing import Union

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pdPYTHON

def subset_resample(fpath, sample_freq, start_date, end_date=None):

df = pd.read_csv(fpath)

df.set_index(pd.to_datetime(df["INTERVAL_TIME"]), inplace=True)

df.sort_index(inplace=True)

if end_date:

date_subset = df.loc[start_date: end_date].copy()

else:

date_subset = df.loc[start_date].copy()

resampled_data = date_subset.resample(sample_freq)

return resampled_dataCall our function to read and subset the data.

PYTHON

fp = "../../data/ladpu_smart_meter_data_01.csv"

data_subset_resampled = subset_resample(fp, "D", "2019-01", end_date="2019-06")

print("Data type of returned object:", type(data_subset_resampled))OUTPUT

Data type of returned object: <class 'pandas.core.resample.DatetimeIndexResampler'>As before, we will aggregate the data to daily total power consumption. We will use these daily totals to explore and make predictions based on weekly trends.

PYTHON

daily_usage = data_subset_resampled['INTERVAL_READ'].agg([np.sum])

print(daily_usage.info())

print(daily_usage.head())OUTPUT

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

DatetimeIndex: 181 entries, 2019-01-01 to 2019-06-30

Freq: D

Data columns (total 1 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 sum 181 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(1)

memory usage: 2.8 KB

None

sum

INTERVAL_TIME

2019-01-01 7.5324

2019-01-02 10.2534

2019-01-03 6.8544

2019-01-04 5.3250

2019-01-05 7.5480This time, instead of plotting the daily total power consumption we

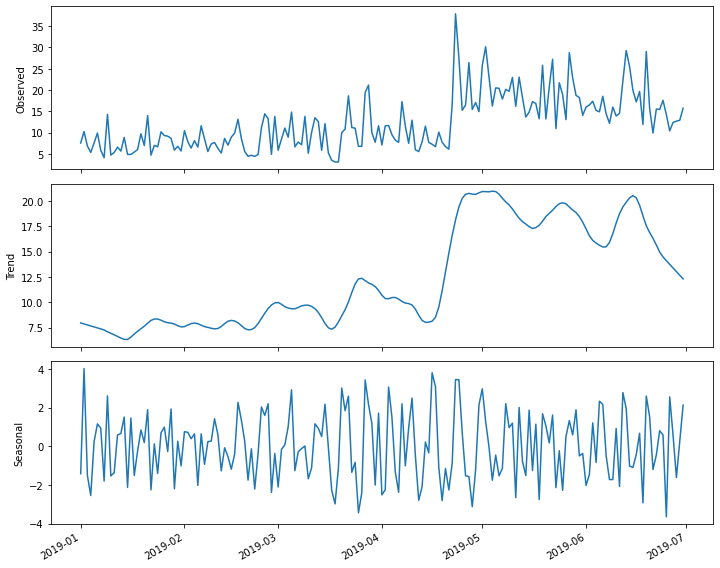

will use the statsmodels STL method to create

a decomposition plot of the time-series. The decomposition plot is

actually a figure that includes three subplots, one for the observed

values, which is essentially the plot we have been rendering in the

other sections of this lesson when we first inspect the data.

The other two plots include the overall trend and the seasonal trends. Because we set the period argument to 7 when we created the figure, the returned Seasonal subplot is represented as a series of 7 day intervals. A weekly trends is evident.

PYTHON

decomposition = STL(daily_usage['sum'], period=7).fit()

fig, (ax1, ax2, ax3) = plt.subplots(nrows=3, ncols=1,

sharex=True, figsize=(10,8))

ax1.plot(decomposition.observed)

ax1.set_ylabel('Observed')

ax2.plot(decomposition.trend)

ax2.set_ylabel('Trend')

ax3.plot(decomposition.seasonal)

ax3.set_ylabel('Seasonal')

fig.autofmt_xdate()

plt.tight_layout()

Determine orders of SARIMA(p, d, q)(P, D, Q)m processes

The parameters of the seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average model are similar to those of the ARIMA(p, d, q) model covered in the previous section. The difference is that in addition to specifying the orders of the ARIMA(p, d, q) processes, we are additionally specifying the same parameters, here represented as (P, D, Q) over a given period, m.

We can use differencing to determine the integration order, d, and the seasonal integration order, D.

As we have seen, our time-series is non-stationary.

PYTHON

ADF_result = adfuller(daily_usage['sum'])

print(f'ADF Statistic: {ADF_result[0]}')

print(f'p-value: {ADF_result[1]}')OUTPUT

ADF Statistic: -2.4711247025051346

p-value: 0.1226589853651796First order differencing results in a stationary time-series.

PYTHON

daily_usage_diff = np.diff(daily_usage['sum'], n = 1)

ADF_result = adfuller(daily_usage_diff)

print(f'ADF Statistic: {ADF_result[0]}')

print(f'p-value: {ADF_result[1]}')OUTPUT

ADF Statistic: -7.608254715996063

p-value: 2.291404555919546e-11From this we know that the value of the integration order is 1. Since we are interested in a weekly period, we will use a value of 7 for m in the SARIMA(p, d, q)(P, D, Q)m model. In the SARIMAX model, this value is given as s, which is the fourth parameter of the seasonal_order argument.

We will update our AIC function to incorporate these additional arguments. Note that we have not yet determined the seasonal integration order, D.

PYTHON

def fit_eval_AIC(data, order_list, d, D, s):

aic_results = []

for o in order_list:

model = SARIMAX(data, order=(o[0], d, o[1]),

seasonal_order = (o[2], D, o[3], s),

simple_differencing=False)

res = model.fit(disp=False)

aic = res.aic

aic_results.append([o, aic])

result_df = pd.DataFrame(aic_results, columns=(['(p, q, P, Q)', 'AIC']))

result_df.sort_values(by='AIC', ascending=True, inplace=True)

result_df.reset_index(drop=True, inplace=True)

return result_dfUsing the definition of a SARIMA(p, d, q)(P, D, Q)m model, we note that when the seasonal (P, D, Q) orders are zero, that is equivalent to an ARIMA(p, d, q) model, with the addition of a specified period m. Recall that the period parameter in the SARIMAX model is given as s. With this in mind we can use the function to fit and evaluate a range of possible ARMA(p, q) orders as before.

PYTHON

ps = range(0, 8, 1)

qs = range(0, 8, 1)

Ps = [0]

Qs = [0]

d = 1

D = 0

s = 7

ARIMA_order_list = list(product(ps, qs, Ps, Qs))

print(ARIMA_order_list)

```output

[(0, 0, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0, 0), (0, 2, 0, 0), (0, 3, 0, 0), (0, 4, 0, 0), (0, 5, 0, 0), (0, 6, 0, 0), (0, 7, 0, 0), (1, 0, 0, 0), (1, 1, 0, 0), (1, 2, 0, 0), (1, 3, 0, 0), (1, 4, 0, 0), (1, 5, 0, 0), (1, 6, 0, 0), (1, 7, 0, 0), (2, 0, 0, 0), (2, 1, 0, 0), (2, 2, 0, 0), (2, 3, 0, 0), (2, 4, 0, 0), (2, 5, 0, 0), (2, 6, 0, 0), (2, 7, 0, 0), (3, 0, 0, 0), (3, 1, 0, 0), (3, 2, 0, 0), (3, 3, 0, 0), (3, 4, 0, 0), (3, 5, 0, 0), (3, 6, 0, 0), (3, 7, 0, 0), (4, 0, 0, 0), (4, 1, 0, 0), (4, 2, 0, 0), (4, 3, 0, 0), (4, 4, 0, 0), (4, 5, 0, 0), (4, 6, 0, 0), (4, 7, 0, 0), (5, 0, 0, 0), (5, 1, 0, 0), (5, 2, 0, 0), (5, 3, 0, 0), (5, 4, 0, 0), (5, 5, 0, 0), (5, 6, 0, 0), (5, 7, 0, 0), (6, 0, 0, 0), (6, 1, 0, 0), (6, 2, 0, 0), (6, 3, 0, 0), (6, 4, 0, 0), (6, 5, 0, 0), (6, 6, 0, 0), (6, 7, 0, 0), (7, 0, 0, 0), (7, 1, 0, 0), (7, 2, 0, 0), (7, 3, 0, 0), (7, 4, 0, 0), (7, 5, 0, 0), (7, 6, 0, 0), (7, 7, 0, 0)]Note that we are generating a much longer order_list to account for the combinations of multiple orders. The following step may take a few minutes to complete.

Create a training dataset that includes all but the last seven days of the time-series, then fit the different models on the training data.

PYTHON

train = daily_usage['sum'][:-7]

ARIMA_result_df = fit_eval_AIC(train, ARIMA_order_list, d, D, s)

print(ARIMA_result_df)OUTPUT

(p, q, P, Q) AIC

0 (3, 4, 0, 0) 1031.133360

1 (2, 2, 0, 0) 1031.647489

2 (1, 3, 0, 0) 1031.786064

3 (1, 2, 0, 0) 1032.481145

4 (3, 5, 0, 0) 1032.898114

.. ... ...

59 (4, 0, 0, 0) 1046.805280

60 (3, 0, 0, 0) 1053.364985

61 (2, 0, 0, 0) 1055.571767

62 (1, 0, 0, 0) 1073.574512

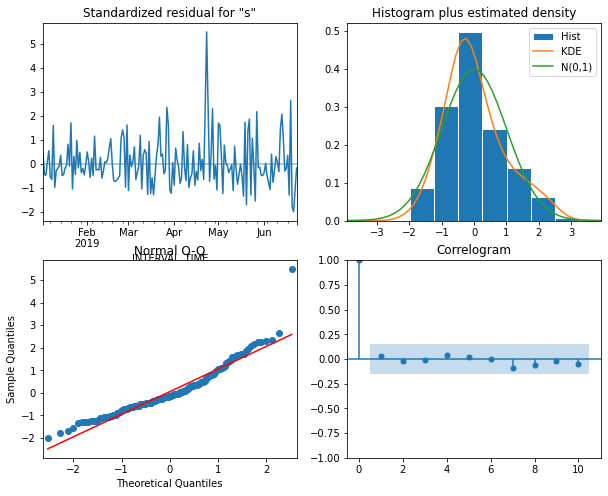

63 (0, 0, 0, 0) 1093.603695With the comparatively best orders of the p and q parameters, we can run the SARMIAX model and render a diagnostic plot before forecasting.

PYTHON

ARIMA_model = SARIMAX(train, order=(3,1,4), simple_differencing=False)

ARIMA_model_fit = ARIMA_model.fit(disp=False)

ARIMA_model_fit.plot_diagnostics(figsize=(10,8));

The plot indicates that none of the assumptions of the model have been violated. We now retrieve seven day’s worth of predictions from the model and add them to a test dataset for later evaluation.

PYTHON

test = daily_usage.iloc[-7:]

# Append ARIMA predictions to test set for comparison

ARIMA_pred = ARIMA_model_fit.get_prediction(174, 181).predicted_mean

test['ARIMA_pred'] = ARIMA_pred

print(test)OUTPUT

sum ARIMA_pred

INTERVAL_TIME

2019-06-24 17.5740 17.617429

2019-06-25 14.1876 14.289460

2019-06-26 10.3902 15.595329

2019-06-27 12.3936 14.154636

2019-06-28 12.6720 16.503719

2019-06-29 12.8916 16.395582

2019-06-30 15.7194 18.233482We can also add a naive seasonal baseline, similar to the baseline metric used in the last section

OUTPUT

sum ARIMA_pred naive_seasonal

INTERVAL_TIME

2019-06-24 17.5740 17.617429 19.6512

2019-06-25 14.1876 14.289460 11.8926

2019-06-26 10.3902 15.595329 29.0688

2019-06-27 12.3936 14.154636 15.6822

2019-06-28 12.6720 16.503719 9.8856

2019-06-29 12.8916 16.395582 15.5208

2019-06-30 15.7194 18.233482 15.4338With the basline forecast and an ARIMA(3, 1, 4) forecast in place, we now need to determine the orders of the seasonal (P, D, Q) processes for the SARIMA model.

For the most part, this is similar to the process we have been using to fit and evaluate different models using their AIC values. In this case we only need to add combinations of the (P, Q) orders to our order_list. But first we need to determine the seasonal integration order, D. We can use differencing to do this. Here we set the n argument for the distance between difference values to 7, since we are differencing values across seven day periods.

PYTHON

daily_usage_diff_seasonal = np.diff(daily_usage['sum'], n = 7)

ADF_result = adfuller(daily_usage_diff_seasonal)

print(f'ADF Statistic: {ADF_result[0]}')

print(f'p-value: {ADF_result[1]}')OUTPUT

ADF Statistic: -11.91407313712363

p-value: 5.2143503070551235e-22The result indicates that the source time-series over 7 day intervals is stationary, so since no further differencing is needed we will set the seasonal integration order, D, to zero.

Now, create an order_list that includes a range of values for (P, Q). In this case we will not print the full list because it is long.

PYTHON

ps = range(0, 4, 1)

qs = range(0, 4, 1)

Ps = range(0, 4, 1)

Qs = range(0, 4, 1)

SARIMA_order_list = list(product(ps, qs, Ps, Qs))With the addition of the integration and seasonal integration orders, as well as the seasonal period, we can now fit the models. This may also take a some time to run.

PYTHON

d = 1

D = 0

s = 7

SARIMA_result_df = fit_eval_AIC(train, SARIMA_order_list, d, D, s)

print(SARIMA_result_df)OUTPUT

(p, q, P, Q) AIC

0 (1, 2, 2, 2) 1028.342573

1 (2, 2, 2, 2) 1029.074015

2 (1, 3, 2, 2) 1029.319536

3 (1, 2, 2, 3) 1029.588997

4 (1, 2, 3, 2) 1029.609838

.. ... ...

251 (0, 0, 1, 3) 1094.831557

252 (0, 0, 1, 1) 1095.425574

253 (0, 0, 0, 1) 1095.599186

254 (0, 0, 1, 0) 1095.600553

255 (0, 0, 3, 3) 1095.666939

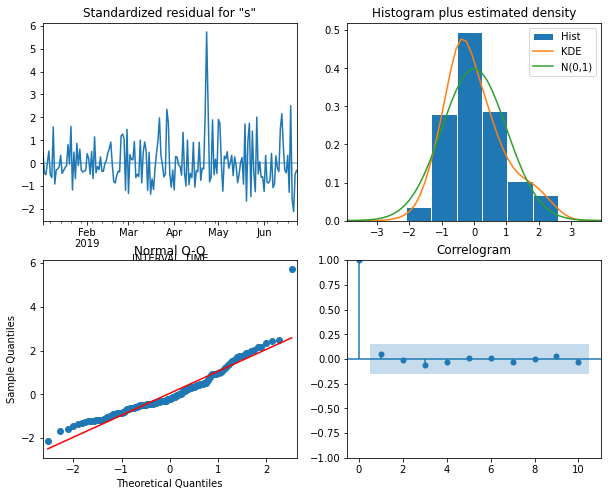

[256 rows x 2 columns]Among all the models fitted, the comparative best is a SARIMA(1, 1,

2)(2, 0, 2)7 model. We pass this to the SARIMAX model in the

statsmodels library and generate a diagnostic plot before

retrieving forecasts.

PYTHON

SARIMA_model = SARIMAX(train, order=(1,1,2), seasonal_order=(2,0,2,7), simple_differencing=False)

SARIMA_model_fit = SARIMA_model.fit(disp=False)

SARIMA_model_fit.plot_diagnostics(figsize=(10,8));

Forecast and evaluate the performance of the SARIMA model

The plot indicates that none of the assumptions of the model are violated, so we retrieve seven days’ worth of predictions from the model and add them as a new column to our test dataset for evaluation.

PYTHON

SARIMA_pred = SARIMA_model_fit.get_prediction(174, 181).predicted_mean

test['SARIMA_pred'] = SARIMA_pred

print(test)OUTPUT

sum ARIMA_pred naive_seasonal SARIMA_pred

INTERVAL_TIME

2019-06-24 17.5740 17.617429 19.6512 15.595992

2019-06-25 14.1876 14.289460 11.8926 13.144431

2019-06-26 10.3902 15.595329 29.0688 15.472899

2019-06-27 12.3936 14.154636 15.6822 13.574806

2019-06-28 12.6720 16.503719 9.8856 16.512553

2019-06-29 12.8916 16.395582 15.5208 13.932104

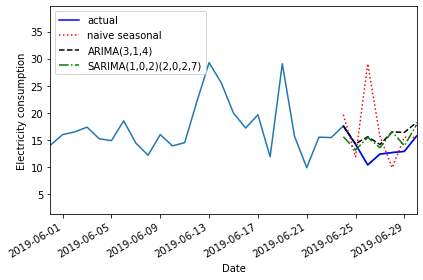

2019-06-30 15.7194 18.233482 15.4338 17.803156Plotting the last month of the time-series, including the forecast, suggests that the ARIMA and SARIMA models performed comparably.

PYTHON

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(daily_usage['sum'])

ax.plot(test['sum'], 'b-', label='actual')

ax.plot(test['naive_seasonal'], 'r:', label='naive seasonal')

ax.plot(test['ARIMA_pred'], 'k--', label='ARIMA(11,1,0)')

ax.plot(test['SARIMA_pred'], 'g-.', label='SARIMA(0,1,1)(0,1,1,12)')

ax.set_xlabel('Date')

ax.set_ylabel('Electricity consumption')

ax.legend(loc=2)

ax.set_xlim(18047, 18077)

fig.autofmt_xdate()

plt.tight_layout()

Evaluatinf the mean absolute error shows that the SARIMA model performed slightly better.

PYTHON

mae_naive_seasonal = mean_absolute_error(test['sum'], test['naive_seasonal'])

mae_ARIMA = mean_absolute_error(test['sum'], test['ARIMA_pred'])

mae_SARIMA = mean_absolute_error(test['sum'], test['SARIMA_pred'])

print("Mean absolute error, baseline:", mae_naive_seasonal)

print("Mean absolute error, ARIMA(3, 1, 4):", mae_ARIMA)

print("Mean absolute error, SARIMA(2, 0, 2, 7):", mae_SARIMA)OUTPUT

Mean absolute error, baseline: 4.577228571428571

Mean absolute error, ARIMA(3, 1, 4): 2.423033958158726

Mean absolute error, SARIMA(2, 0, 2, 7): 2.321413443652824Key Points

- Use the seasonal_order(P, D, Q, m) argument of the SARIMAX model to specify the order of seasonal processes.