Managing code

Last updated on 2023-09-06 | Edit this page

Estimated time 50 minutes

Overview

Questions

What is the role of data wrangling?

What is literate programming?

How to use data visualisation for insight and communication?

What are the main objectives and best practices for testing and reviewing code?

When can continuous integration help?

Objectives

- Understand the basics of coding

- Understand the advantages of modular code

- How to foster good practices:

- using code review

- using tests

- Discuss the importance of code quality, modular programming, and code testing for reusable error-free code.

- Encourage researchers to combine code with documentation to communicate their work.

Basics of coding

As a project manager, you do not need to code or know how coding works. However, it is important to understand the data workflow and foster documentation, as well as coding best practices, such that you can understand the analysis.

This chapter gives a small introduction into coding and data analysis workflow, code modularity, and then how foster good code with tests and review.

Analysis workflow

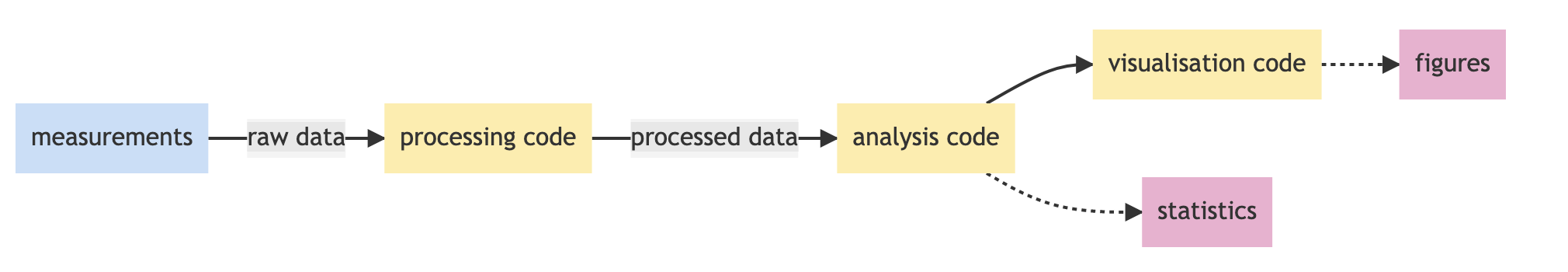

A usual workflow involves some data processing, before the actual analysis can be done. Statistical analysis and figure production should be decided before the data is looked at to prevent harking. Explorative analysis (looking for correlation and interpretation of the results) can be done anytime, as long as no hypothesis is rejected from that analysis.

Data (pre-)processing

Code that cleans and processes data (processing code) provides the very beginning of the data analysis pipeline: starting with raw data and resulting in processed data. When the data was not collected in a computer readable format, or when metadata is missing, this step can be the most time consuming of all.

Data wrangling involves cleaning data so it can be easily read and analysed by machines. It can also involve integration, extraction, removing missing points, and anything that makes data useable and functional. Regardless of the methods, the code involved with data cleaning steps should be carefully documented so that the steps involved can be repeated from raw data to cleaned data.

Data wrangling—also called data cleaning, data remediation, or data munging—refers to a variety of processes designed to transform raw data into more readily used formats. The exact methods differ from project to project depending on the data you’re leveraging and the goal you’re trying to achieve.

Some examples of data wrangling include:

- Merging multiple data sources into a single dataset for analysis,

- Identifying gaps in data (for example, empty cells in a spreadsheet) and either filling or deleting them,

- Deleting data that’s either unnecessary or irrelevant to the project you’re working on,

- Identifying extreme outliers in data and either explaining the discrepancies or removing them so that analysis can take place.

Data wrangling can be a manual or automated process. In scenarios where datasets are exceptionally large, automated data cleaning becomes a necessity.

Cleaning data means it can be easily read and analysed by machines and used in analysis pipelines. It can involve changing labels, subsetting, integration, extraction, removing missing points, and anything that makes data usable and functional.

Regardless of the methods, the code involved in data cleaning steps should be carefully documented so that the steps involved can be repeated from raw data to clean data. When reviewing this type of code, consider whether the steps involved are readable and in the correct order. Especially, when filtering data out, this should be consistent and indicated in the main method description.

Data visualisation, Analysis and Statistics

Visualising data before designing the data analysis is a form of harking, as you will cherry pick your data (filtering some data out) or cherry pick an analysis (what looks promising). You should always design your analysis before visualising the data, or use visualised data as training data, not included in the final analysis.

With readable, clean, processed data, the next stage of the data pipeline is analysis.

Depending on your computational project, this may involve elaborate and complex analyses, modelling, simulation, and even machine learning. However, even if this step is just running a single statistics test, keeping the code documented and modular in clearly defined steps is key.

Here is an example of applying a Butterworth filter to some data in Python. The specifics don’t matter, you can consider this code pseudocode for any kind of analysis step.

genomeProject/analysis/01_butterworth_filter.py

#### 01_butterworth_filter, v1.0

##this code read processed data and apply a low pass filter,

## the output variable is called filtered_data

# Import dependencies

import numpy as np

from scipy.signal import butter,filtfilt

# (A) Read processed data from file

df = pd.read_csv('genomeProject/data/220103_GenomicData_processed.csv')

# (B) Defining filter parameters

T = 5.0 # Sample Period

fs = 30.0 # sample rate, Hz

cutoff = 2 # desired cutoff frequency of the filter, Hz

nyq = 0.5 * fs # Nyquist Frequency

order = 2 # quadratic

n = int(T * fs) # total number of samples

# (C) Define the Butterworth Filter Function

def butter_lowpass_filter(data, cutoff, fs, order):

normal_cutoff = cutoff / nyq

# Get the filter coefficients

b, a = butter(order, normal_cutoff, btype='low', analog=False)

filtered_data = filtfilt(b, a, data)

return filtered_data

# (D) Apply Butterworth Filter Function to the data

filtered_data = butter_lowpass_filter(df, cutoff, fs, order)

Challenge

genomeProject/analysis/01_bf.py

import numpy as np

from scipy.signal import butter,filtfilt

df = pd.read_csv('genomeProject/data/220103_GenomicData_processed.csv')

normc = 2 / 15

b, a = butter(2, normc, btype='low', analog=False)

filtered_data = filtfilt(b, a, df)

The code above will give the same result, why is the first one better on the long run ?

- easier to read for non-coders

- commented

- variables easy to change

- better names

- function reusable + possibility to write tests

- the processed data is read into the script. Next, (B) the fixed

parameters are set and named with comments. These fixed numbers are

saved as variables with names. In (C) the filter itself is written as a

Python Function, which means it can be called multiple times throughout

the script. Because the parameters are not written into the function

directly (so it doesn’t say

b, a = butter(2, 15,btype='low', analog=False)but instead uses variables) this code is reusable without having to paste and edit the numbers every time you apply a function.

You can also call this function in other scripts. It can make sense to produce a file with the functions inside that can be imported into different scripts in case other projects also have similar methods. This is known as a package or library. This means altering a function doesn’t mean searching across every file on every project and changing it dozens of times.

Case Study

A postdoc wrote a helpful series of functions for data analysis with neurophysiology recordings. The postdoc wrote them as reuseable, and so two PhD students copied and pasted these blocks of code into their code and used it to analyse the data for their projects.

The postdoc later discovers a better way of writing the functions. One PhD student also wants to change the method and so has to search through his files to replace the code. The other PhD student wants the old method in some files and the new method in others, and so does not change all of them. It is therefore complex to follow the differences in the methods across the projects, and this is very open to errors in typos.

Instead, the postdoc could have saved his functions in the lab’s private repo which becomes the master copy and students pull from this. With the functions saved in a library, the PhD students can import them into their scripts. Now when the postdoc changes the functions and saves them to the repo, PhD students can choose to update their version of the functions. The students should document which version they have used.

The output of the analysis code may be statistics results that are reported in a paper, and therefore the steps required to reproduce them are critically important.

Figures for Communicating Results

When working with data sets,

ggplot(in R) ormatplotlib/seaborn(in Python) libraries provide attractive figures that can be produced very quickly. Visualising data should not not wait for the point of publication, and can be used to explore data from the start, and also illustrate methodology. This is particularly valuable in Jupyter Notebooks. Code to produce figures should be literate, functional, reuseable in the same way as data cleaning and analysis code. That way future visualisations can be easily updated or reused.

With the analysis complete, data visualisation is usually used to communicate results. The code used to produce figures is often the next step in the data pipeline.

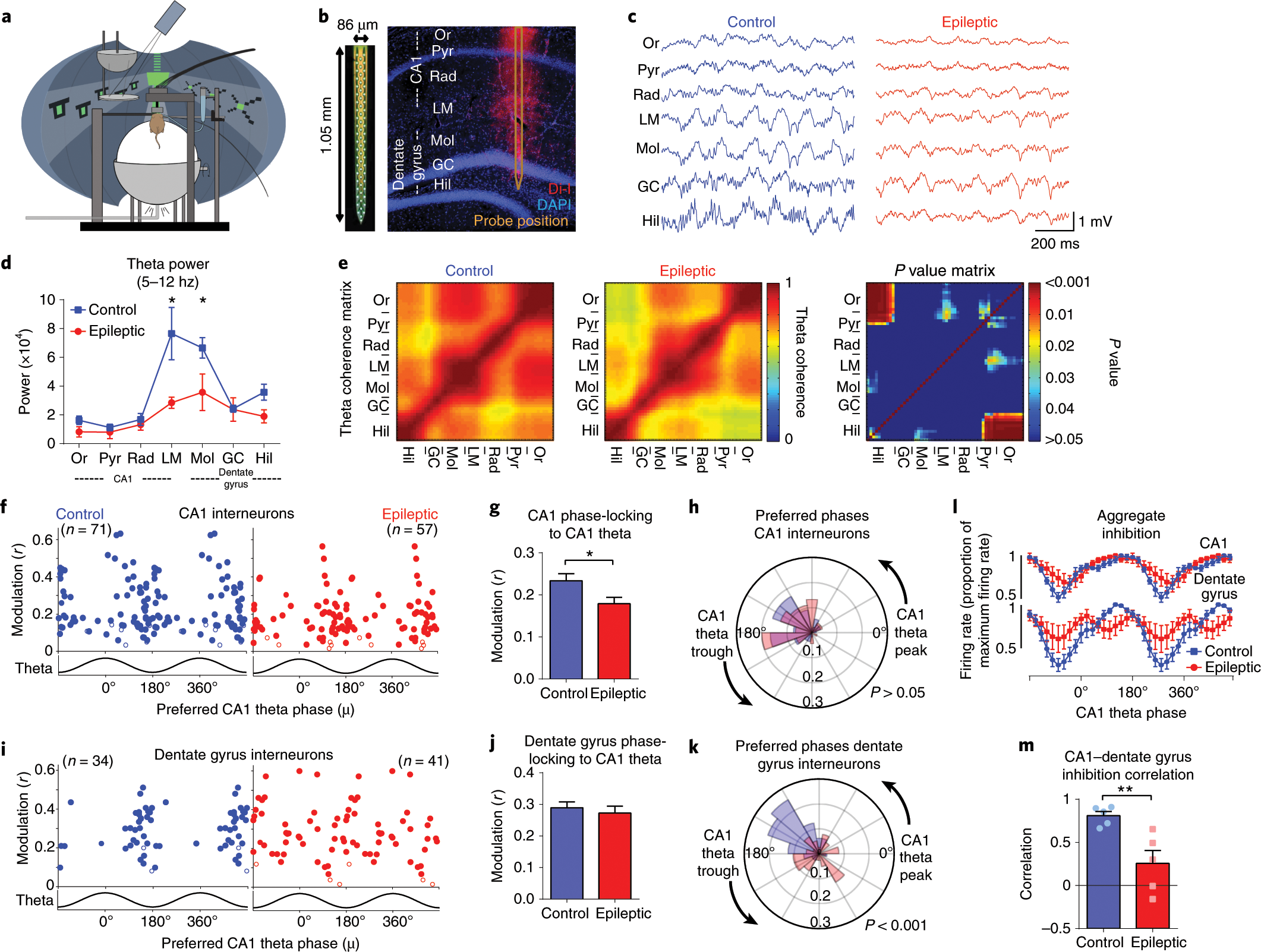

For publications or posters, well-constructed figures improve science communication and help improve the impact of your research. Being able to produce multipanel figures with annotations and different colour schemes is complex but one of the advantages of learning a data science language.

It is therefore worth taking the time for researchers to learn the technical skills in R, Python, or another language to produce visualisations. Producing figures in Excel is limiting and often frustrating, particularly as there are only limited options in layout and type of figure.

Exploring constraints on a wetland methane emission ensemble (WetCHARTs) using GOSAT observations, Parker et al 2020

Spatial transcriptome profiling by MERFISH reveals subcellular RNA compartmentalization and cell cycle-dependent gene expression, Xia et al 2019 https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1912459116

These figures are more than just visualising data, they’re about

communication and require adjusting the styles and formats within

ggplot or matplotlib or other libraries.

As before, any code used to produce visualisations should be reproducible and literate. Often in peer review figures need to be adjusted or altered, and having the code to do so makes the process much simpler.

It is usually cleaner to keep data visualisation code separate from analysis, just to keep a code base organised and modular.

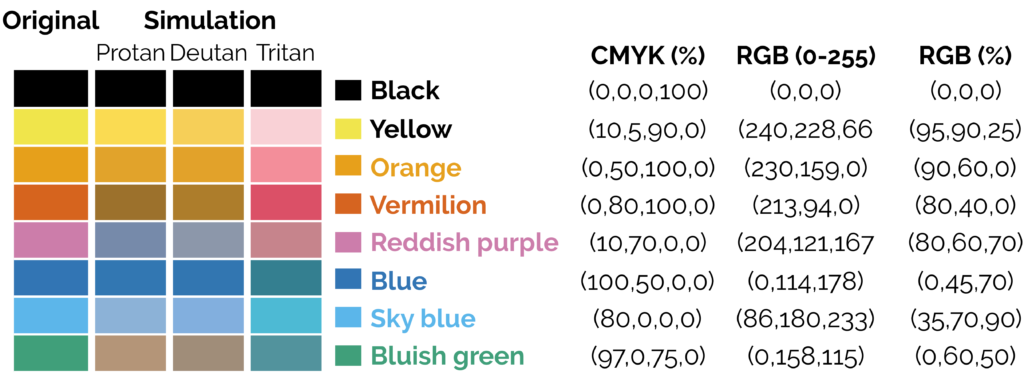

Accessibility

- For simple figures, using shaded vs unshaded and single colour is best when considering publications may be printed in black and white

- Colours should be colourblind friendly, resources are available for this.

- If using a colour map, avoid the standard rainbow. Other rainbows like viridis colour maps can be downloaded. The brightness varies across the rainbow which leads to visual artefacts that do not exist:

The transition between greens to yellow and red are more prominent than the transitions between greens and blues, making stark boundaries that do not exist. A rainbow with equal brightness solves the problem.

Sisneros et al (2016) Chasing Rainbows: A Color-Theoretic Framework for Improving and Preserving Bad Colormaps. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50835-1_36

Also one should keep readability in mind with text size/font and similar considerations

- Data Visualisation as a tool

Statistical analysis

Selection of appropriate statistical method is very important step in analysis of data. A wrong selection of the statistical method not only creates some serious problem during the interpretation of the findings but also affects the conclusion of the study. In statistics, for each specific situation, statistical methods are available to analysis and interpretation of the data. To select the appropriate statistical method, one need to know the assumption and conditions of the statistical methods, so that proper statistical method can be selected for data analysis. Other than knowledge of the statistical methods, another very important aspect is nature and type of the data collected and objective of the study because as per objective, corresponding statistical methods are selected which are suitable on given data. Incorrect statistical methods can be seen in many conditions like use of unpaired t-test on paired data or use of parametric test for the data which does not follow the normal distribution, etc., Two main statistical methods are used in data analysis: descriptive statistics, which summarizes data using indexes such as mean, median, standard deviation and another is inferential statistics, which draws conclusions from data using statistical tests such as student’s t-test, ANOVA test, and many others

Statistics goes outside the scope of this course.

Coding best practices

The order of a script is usually:

- main comments on the script function and goals

- importing all dependencies

- reading inputs, naming outputs

- listing all variables

The latter element is particularly important. Variables are often a decision taken (for instance it could be some threshold value used for filtering data out, a type of low-pass filter used, or a time window that sub-set the data). Defining them at the start of the code makes it easier to change and spot.

In practice, your figure and analysis may well depend on the version of the data, code and these variables, so it is often interesting to include this information into the output of the code. This may take the form of a pdf file, with the figure on the first page, and a table of variables and metadata on the following pages.

Literate Programming

Literate programming is about comments and documentation and telling other humans what is happening in your pipeline. Depending on the scale of your computational projects, you may use one or multiple of these options:

- Inline comments when writing code (directly written in the script file)

- A README file describing what your code does

- An online documentation as a user and developer guide with step-by-step explanation

- Quarto/RMarkdown or Jupyter Notebook

Most of these files can be written in Markdown.

Often, literate programming refers to these notebooks form, where the documentation and the code are integrated in one file, which produce one output (html of pdf most of the time).

This course can be thought as a literate programming content. Its source is markdown and Rmarkdown files, its output is a pdf.

Resources for taking this to next level

- https://the-turing-way.netlify.app/collaboration/new-community.html

- Data Visualisation as a tool

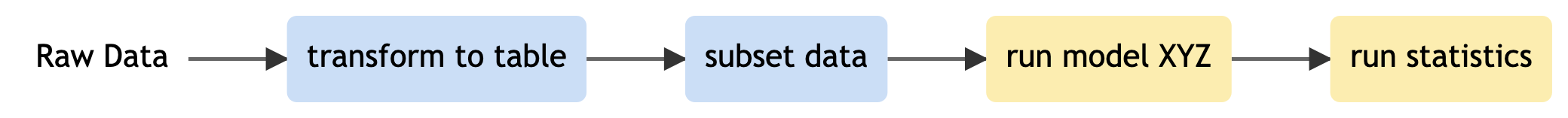

Modular Programming (Functions)

Applying methods from one person’s work and applying it to another problem can take weeks, if not months, of work. Applying methods from publications is even harder: static PDF files can’t describe the lines of code and data that lead to those discoveries. This is an increasingly important problem in the face of growing mistrust in science, and a reproducibility crisis plaguing the sciences.

Instead, functional programming is about writing code that works as modular steps. Each step is clearly commented on and carefully produced so that it can be reused in different contexts. Often when you are analysing data, you need to repeat the same task many times. For example, you might have several files that all need loading and clean in the same way, or you might need to perform the same analysis for multiple species or parameters. Rather than copying and pasting, writing a function and calling that function leads to fewer errors and confusion overall.

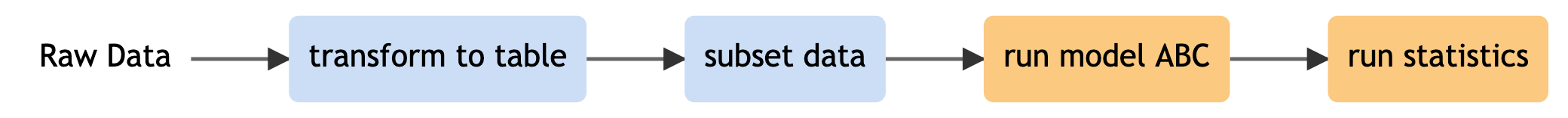

We can think of this on a broad scale, say one student’s computational work has the following steps, where blue shows data cleaning, and yellow the analysis and statistics.

Another student can take reuse the data cleaning and initial visualisation steps because her data was from the same source and is in the same format. She can later add her own model:

On the micro-scale, functional programming ensures that each code file itself is comprised of modular blocks, whether for data processing, analysis pipeline, simulation and so on. Depending on your programming language, these may be used as a package or a library or saved in files that are available for installation. Just the same as the diagram above, making sure functions are robust and reuseable means they can be shared throughout different workflows and for different projects.

Training in functional programming is usually an excellent pre-requisite for members of your lab.

A first step can be to draw out and create diagrams to plan code before starting and identifying the modular steps involved. This does not require technical knowledge of a language and is, therefore, a great exercise for direct supervision. You can find practical details on reproducible code in the Guides to Better Science by British Ecological Society.

Code Testing

You should not skip writing tests because you are short on time, you should write tests because you are short on time.

The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY

4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY

4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

Writing a test to prove things work right now is useless (duh, you know what use case you designed it for, of course it will work). Defending your project against the future idiot who is going to f things up (most likely yourself) is the right attitude and will lead to proper tests. Love it! https://mstdn.social/@flip1/108951972043173555

It is very, very easy to make mistakes when coding. A single wrong use of a character can cause a program’s output to be entirely wrong. Missing one data point, writing plus instead of minus symbol or using feet instead of meters might be a genuine human mistake, but in research, the results can be catastrophic. Careers can be damaged/ended, vast sums of research funds can be wasted, and valuable time may be lost exploring incorrect avenues. This is why code testing is vital.

Testing is a learned skill that needs to become a part of working on/improving a project. After changing their code, researchers should always check that their changes or fixes have not broken anything. It also helps deciding when dependencies can be updated. There are several different kinds of testing and each has best practices specific to them.

A few important testing types

- Smoke testing: Very brief initial checks that ensure the basic requirements required to run the project hold. If these fail there is no point in proceeding to additional levels of testing until they are fixed.

- Unit testing: A level of the software testing process where individual units of a software are tested. The purpose is to validate that each unit of the software performs as designed.

- Integration testing: A level of software testing where individual units are combined and tested as a group. The purpose of this level of testing is to expose faults in the interaction between integrated units.

- System testing: A level of the software testing process where a complete, integrated system is tested. The purpose of this test is to evaluate whether the system as a whole gives the correct outputs for given inputs.

No matter the type of testing you use, general guidance is to start by writing any test and make a habit of running tests often.

- Make improvements where you can, and do your best to include tests with new code you write even if it’s not feasible to write tests for all the code that’s already written.

- Make the cases you test as realistic as possible. If for example, you have dummy data to run tests on you should make sure that data is as similar as possible to the actual data. If your actual data is messy with a lot of null values, so should your test dataset be.

There are tools available to make writing and running tests easier, these are known as testing frameworks. Find one you like, learn about the features it offers, and make use of them.

Writing tests typically encourage researchers to write cleaner, more modular code as such code is far easier to write tests for, leading to an improvement in code quality. As well as advantaging individual researchers testing also benefits research as a whole. It makes research more reproducible by answering the question “how do we even know this code works”. To gain an in-depth understanding of different kinds of tests, please see Code Testing chapter in The Turing Way.

Code Review

Testimonial

The most difficult part of writing code is always to make it understandable to other people, including yourself a few months down the track. There’s certainly no shame in finding out that your code wasn’t as easy to understand or use as you’d hoped, so don’t take it personally when it happens (which it always does, at least in my experience), but treat it as an opportunity to improve.

Fernando Perez, Code reviews: the lab meeting for code

A simple objective of the review process is to catch bugs and elementary errors that might have been missed during the development phase. Code review can also help improve the overall quality while ensuring that code is readable and easy to understand. As a group leader, you can also make sure code is functional and literate as early as possible, and encourage your students to avoid messy “good enough” code that causes chaos later.

Code review is often done in pairs, with each reviewer also having some of their code reviewed by their partner. Doing this can help programmers to see and discuss issues and alternative approaches to tasks, and to learn new tips and tricks.

The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

There are different methods for code review.

Synchronous - Pair Programming

Helping the student go through their scripts, catch errors and debug side by side

- The PI sits down with her PhD student who has been writing a function for cleaning bioinformatics data.

- The PI knows Python well and takes the opportunity to discuss code while helping their student organise the code better.

- The student shows the PI some odd errors and so they run some tests with expected outcomes to find what the problem is and solve it.

- The PhD student learns and applies to test practices to help make code robust.

The problem with synchronous coding sessions is making time for it and whether or not the supervisor has experience with the specific language.

Synchronous - Group Code Tour or Informal Walkthroughs

Narrating code and software steps

The researcher may present their pipeline to describe the logical steps using documentation, pseudocode, or describing how to run the code.

- A postdoc has been working on some analysis that provides statistics results that he hopes to publish soon. During a lab meeting, the postdoc presents the steps of the analysis code as logical steps.

- The lines of code are shown for those in the meeting that know R, but the postdoc explains the steps verbally as well for those who don’t understand R.

- The group discuss and provides comments on the choices and order of the analysis pipeline, a PhD student notices a jump in logic that wasn’t picked up previously, and an advanced R user in the lab makes suggestions about making some parts run faster.

These sessions do not rely on everyone knowing the language, and it is the responsibility of the coder to present their work clearly and logically for everyone to follow. Group discussions can be very informative for everyone involved and put the analysis under scrutiny.

Suggestions for the meeting leader

- Keep it a safe environment, i.e. make sure chastising is relatively gentle even when deserved (but do point out when code doesn’t meet the required standard – frame it as a learning experience though).

- Make sure there’s a core of vocal participants so it isn’t always you.

- Make it clear when you’re presenting yourself that your code isn’t perfect, point out some of those imperfections yourself if the audience is slow to do so, and do present yourself.

- Patiently explain when things are not wrong but just stylistic differences (but make it clear that some styles are bad, often helpful e.g. asking people to guess what a function returns from its name).

Shared by Rob Knight with Fernando Perez in the post Code reviews: the lab meeting for code

Asynchronous - I’ll get back to you on that

Making sure everyone is free at the same time for a lab meeting can be challenging. Hence, asynchronous code review practices are more suitable for busy supervisors or collaborators in different time zones.

The asynchronous review process allows others to run the code themselves using a reproducible environment, or simply reads through the scripts and share their feedback asynchronously.

Consider a scenario:

A postdoc has created a model in Python and creates a Binder with all the dependencies necessary. She sends the file to her supervisor who can run the code within her browser, no installation is required. The supervisor can then run the code herself to review it and check the individual parts over the next week. The supervisor adds a commented version of the script to the postdoc’s repo with a merge request.

Reviewing code in small chunks incrementally as the project is developing can help make the code review process a lot more efficient. Asynchronous feedback removes the time pressure but can be easily forgotten!

Testimonial

Reviewing more than 400 lines of code (LoC) can have an adverse impact on your ability to find bugs, and in fact, most are found in the first 200 lines. - Recommendation from Code Review at Cisco Systems

5 code review best practices. Work Life by Atlassian, Usman Ghani

Multiple people can also review the code asynchronously.

Callout

Turing Way: Recommendations for Code Reviewing

Unlike traditional, “academic-style” peer review, most code review systems have several advantages: they’re rarely anonymous, they’re public-facing, and without the broker of an editor, contact between reviewer and reviewee can be direct and rapid. This means code review is typically a fast, flexible, and interactive process.

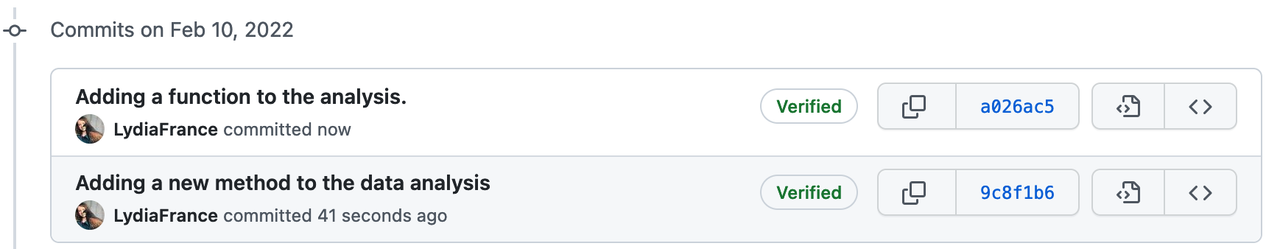

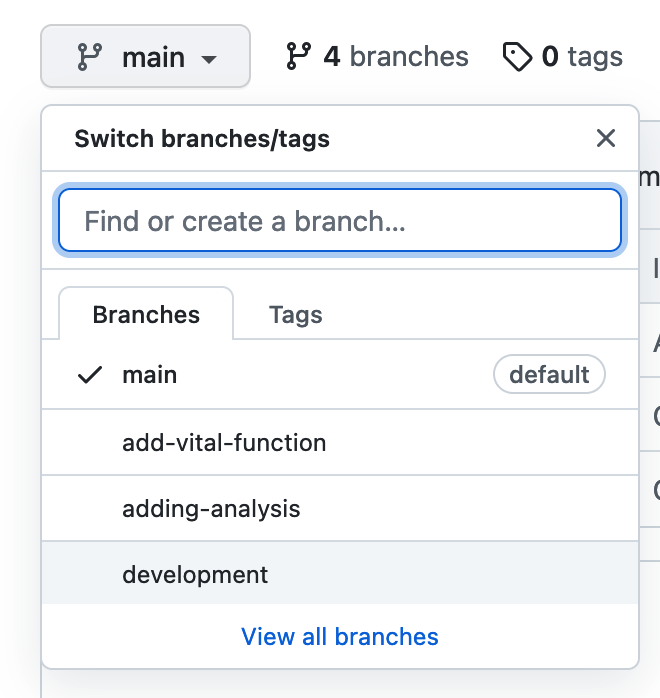

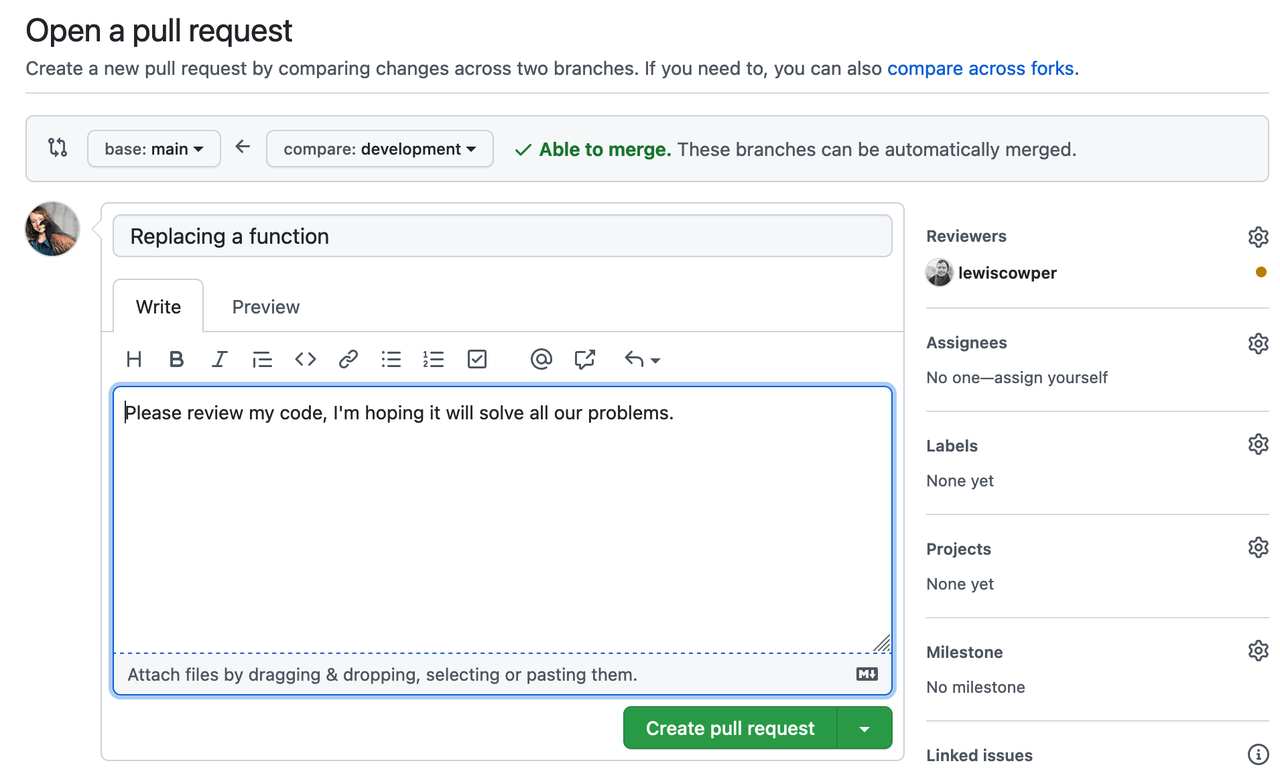

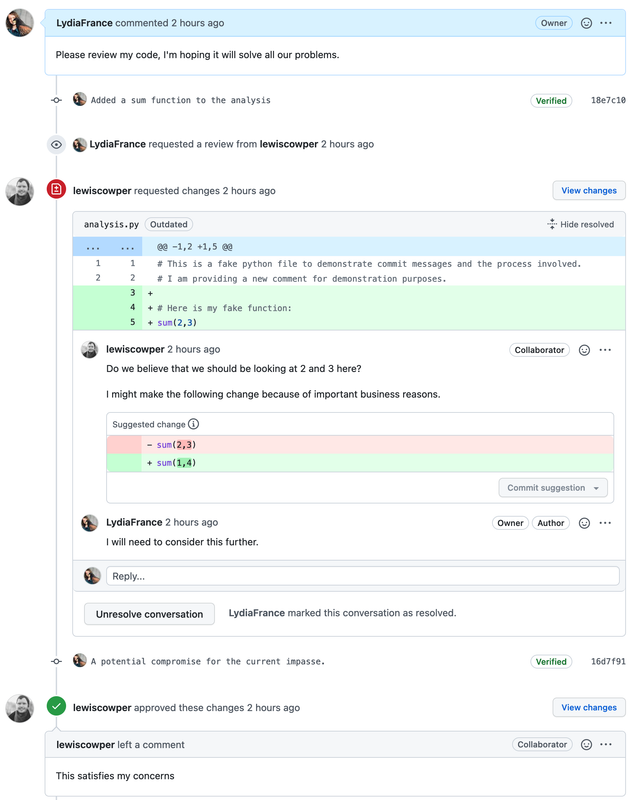

Commit changes: uploading snapshots when the code changes. The history of all changes are therefore saved and can be reverted.

Branching: keep a version of the code separate while making experimental changes or keeping track of collaborative work. Can try out new functionality or edit in parallel without impacting the code base.

Pull Request: Bring the changes made on a branch over to the main code base. Can be used to request a code review (see Reviewers on the right panel)

Review: A pull request can be reviewed and commented on.

Author: Lydia France (Junior Data Scientist, The Alan Turing Institute, UK)

Reviewing is not about creating more work, nor the PI rewriting everything

Instead, it is just another part of peer review and accountability within the scientific process. It is also an opportunity for everyone to learn better practices from each other, and solve issues that have plagued one person for weeks!

Callout

Scientists are very aware that their understanding of code dissipates over time and that this is a large hidden cost. Equally, they suspect that they spend a lot of time reinventing wheels. They may not know how code review will help with that, but they hope that it will.

One of the mentors expected scientists to overhaul complete code bases. The advice from one mentor was cogent: if you check the docstring and write a test every time you touch a method, the code improvements will accumulate over time with minimal effort.

Someone who isn’t intimately involved with your project should understand from the module documentation and the comments what you are trying to do, what approach you’re taking, and why they should expect it to work.

Take some time to prepare a presentation about your code that will answer the above questions even for someone who hasn’t read the code. You’re more likely to get useful feedback, rather than nitpicking about syntax, if the audience can see the big picture.

Keep it a safe environment, i.e. make sure chastising is relatively gentle even when deserved (but do point out when code doesn’t meet the required standard – frame it as a learning experience though).

Marian Petre and Greg Wilson. “Code review for and by scientists: preliminary findings.” (2014).

For further considerations in code review, please read Code Reviewing Process chapter in The Turing Way.

What to look for during Code Review

Reviewing code makes a big difference. Knowledge of the language is not always necessary!

These are very common, everyone does this.

Bugs/Potential bugs

- Repetitive code

- Code saying one thing, documentation saying another

- Off-by-one errors

- Making sure each function does one thing only

- Lack of tests and sanity checks for what different parts are doing

- Magic numbers (a number hardcoded in the script)

Unclear, messy code

- Bad variable/method names

- Inconsistent indentation

- The order of the different steps

- Too much on one line

- Lack of comments and signposting

Fragile and non-reusable code

- Tailor-made and manual steps

- Only works with the given data

Modified from What to look for when code reviewing

Benefits of Code Review

Testimonial

In a group of 11 programs developed by the same group of people, the first 5 were developed without reviews. The remaining 6 were developed with reviews. After all the programs were released to production, the first 5 had an average of 4.5 errors per 100 lines of code. The 6 that had been inspected had an average of only 0.82 errors per 100. Reviews cut the errors by over 80 percent.

Code Complete by Steve McConnell

The main benefit is finding problems, and finding them early enough that there aren’t frustrating consequences. The penalty for finding a bug once all the figures have been produced and conclusions drawn, or, worst-case scenario, after a publication, is much higher than the penalty for taking the time to review.

For a group leader, the benefits include:

- Better understanding of the projects

- More maintainable and better-documented code that is easy to understand and modify

- Better insight into any problems with data

- Earlier visibility of quality issues

- Group reviews reduce the work burden

- More robust analysis pipelines that can be reused and modified

- High-quality code that can be released

Important things to bear in mind:

Code reviews should not be used to evaluate individuals and their skill levels. An open and safe environment where revealing mistakes and errors should not come with penalties or shame. Code reviews should also be done early and often, to normalise this practice in the research team.

In their book Peer Reviews in Software: A Practical Guide, Karl E. Wiegers says:

The temptation to perfect the product before you allow another pair of eyes to see it. This is an ego-protecting strategy: you won’t feel embarrassed about your mistakes if no one else sees them. …review [is not] a seal of approval but rather in-process quality-improvement activity. Such reluctance has several unfortunate consequences. If your work isn’t reviewed until you think it’s complete, you are psychologically resistant to suggestions for changes.

If the program runs, how bad can it be? You are likely to rationalise away possible bugs because you believe you’ve finished and you’re eager to move on to the next task. Relying on your own desk checking and unit testing ignores the greater efficiency of a peer review for finding many defects*

Group Code Writing

As well as reviewing specific scripts and analyses written by a single individual, can be very beneficial to solving programming problems as a team. Setting aside an afternoon to work as a group will help teach less experienced members of the group and more efficiently solve very difficult problems.

Groups of people working on a specific problem are often known as “Hackathons” in programming. These can last multiple days (hopefully with downtime!). With very large groups, people can work in pairs or small groups with delegated parts of the problem to solve and regularly meet back together to discuss and evaluate. If there is a complex solution in computational methods that most people in the group need, it makes sense to find it together.

Similarly, documentation sprints are useful to dedicate time to regularly bring a codebase to a good minimum standard. Splitting the task across the team as an event, creating documentation and working examples for code repos and releasing it can help others use your computational methods and tools to increase the impact of your work. Having regularly updated documentation also reduces onboarding time for new members picking up the shared methods in the lab.

Group work shares the burden and allows knowledge exchange and support within the team.

Continuous integration

Continuous Integration (CI) is the practice of integrating changes to a project made by individuals into a main, shared version frequently (usually multiple times per day). CI is also typically used to identify any conflicts and bugs that are introduced by changes, so they are found and fixed early, minimising the effort required to do so. Running tests regularly also saves humans from needing to do it manually. By making users aware of bugs as early as possible researchers (if the project is a research project) do not waste a lot of time doing work that may need to be thrown away, which may be the case if tests are run infrequently and results are produced using faulty code. There are many CI service providers, such as GitHub Actions that come with their own advantages and disadvantages.

The Turing Way

project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI:

10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

The Turing Way

project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI:

10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

To learn more about different CI tools and how to use them, please read the Continuous Integration chapter in The Turing Way.

References

- The Turing Way Community. (2021). The Turing Way: A handbook for reproducible, ethical and collaborative research (1.0.1). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5671094. Code Reviewing Process Chapter.

- Fernando Perez, Code reviews: the lab meeting for code

Keypoints

- There are many benefits of code review and this should be implemented and practised in research team culture as early and as frequently as possible.

- Synchronous code review creates opportunities for researchers to get feedback and learn from others in real-time.

- Asynchronous code review is a good practice when working with busy researchers or collaborators in different time zones.