Reducing Emissions

Last updated on 2025-09-19 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What methodologies are available to reduce carbon emissions and how do they differ?

- What is the difference between “net zero” and “carbon neutral” climate commitments?

- How can I reduce the emissions from my use of HPC systems?

Objectives

- Understand different carbon reduction methodologies and their role in meeting climate commitments.

- Appreciate the difference between “net zero” and “carbon neutral” climate commitments.

- Understand matching strategies for energy from renewable sources.

- Introduce potential strategies for reducing emissions from HPC system use.

Introduction

In recent years, many economic actors have sought to reach different climate goals by making various commitments to reducing carbon emissions.

The terms “net zero”, “carbon neutral”, “carbon negative”, and “climate neutral” have been used interchangeably when discussing goals to remove, reduce and prevent carbon emissions. As interest in these targets grows, it is essential to have a common understanding of what these terms mean and how to achieve them through the strategies and measurement procedures we have learnt.

Carbon reduction methodologies

There are many ways to reduce emissions but it’s important to understand the exact mechanism of the reduction when thinking about reduction targets.

Abatement / Carbon Elimination

The Science Based Targets Initiative refers to a mechanism called abatement, which means eliminating sources of CO2 emissions associated with an organisation’s operations and value chain so that they do not enter the atmosphere. The value chain describes the full range of activities needed to create a product or service, from conception to distribution.

Abatement is not enough on its own as there will always be some emissions that cannot be eliminated due to technological or economic constraints, but it must form the core of every emissions reduction strategy.

To balance those residual emissions, we need to look at other mechanisms such as offsets, compensations or neutralisations.

Exercise: Strategies for abatement

Abatement is the critical component of carbon emissions reduction strategies. Pick one of the questions below (the one that is most relevant for your role) and write down some answers:

- Can you think of actions that individual users/researchers could take to implement abatement in their use of HPC systems?

- Can you think of actions that a service operator could take to implement abatement in the operation of HPC systems?

- Can you think of actions that a organisation procuring HPC systems could take to implement abatement when buying HPC systems?

- Individual users:

- Run fewer jobs!

- Reduce wasted resources by having fewer job failures

- Run on systems that minimise emissions (spatial shifting)

- Run when emissions from electricity are lower (temporal shifting)

- Service operators:

- Build scheduler policies to eliminate emissions

- Provide tools and information that allow users to quantify their emissions and measure reductions

- Provide training on carbon emissions and abatement strategies

- Service procurement:

- Purchase the minimum amount of hardware possible for the service

- Build scoring on amount of embodied and operational emissions into procurement process

- Site HPC systems at locations that have low carbon intensities

- Run services for as long as possible

Offsets

Offsets are direct investments in emission-reduction projects through the purchase of carbon credits on the voluntary carbon market (VCM). The VCM is a decentralised market where private actors voluntarily buy and sell carbon credits that represent certified removals or reductions of GHGs from the atmosphere.

To offset emissions, you need to purchase the equivalent volume of carbon credits to compensate for those emitted, where 1 carbon credit corresponds to 1 tonne of CO2 absorbed or reduced.

Various positive benefits can stem from these projects, from ecosystem protection to empowering local communities. However, to ensure these programs are implemented correctly and have the desired effect on the environment and the aim to reach world net zero, there are global standards that they must meet such as Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) and Gold Standard (GS).

HPC-CI and Offsets

There are some limitations to carbon offsets and that is why they are not considered in an HPC-CI metric. For example, imagine two projects, both running on a HPC service that is 100% carbon offset and matched 100% by renewable energy. Project A has invested significant time and resources into making sure it is using resources efficiently, whereas project B uses resources very inefficiently. For the HPC-CI to be a helpful metric, project A needs to score better than project B.

If the HPC-CI considered offsets, both projects would score 0. This would not tell us anything about how efficiently they are using resources. Although project B is emitting more carbon molecules into the atmosphere per unit of output, its score is still 0 and the lowest score is 0, therefore why would it make further investments into improving its carbon efficiency?

HPC services and users need to have plans for how to both eliminate as well as neutralise emissions and the HPC-CI helps them to drive the elimination of emissions due to their use of HPC systems. This makes the HPC-CI a useful tool to help a research project or HPC service reach net zero.

Compensating / Carbon Avoidance

Compensations are actions that organisations or individuals can take to help society avoid or reduce emissions. This is essentially investing in other organisations’ abatement projects.

This includes actions such as:

- Conservation - Credits are created based on carbon not released through protecting old trees.

- Community projects - These projects help communities worldwide, mainly developing ones, by introducing sustainable living methods.

- Waste to energy - These projects capture methane/landfill gas from smaller villages, or human/agriculture waste, and convert it into electricity.

Neutralising / Carbon Removal

Neutralisations are actions that organisations or individuals take to remove carbon from the atmosphere. Neutralisations refer to the removal and permanent storage of atmospheric carbon to counterbalance the effect of releasing CO2 into the atmosphere. This includes actions such as:

- Enhancing natural carbon sinks that remove CO2 from the atmosphere. For example, forest restoration, since photosynthesis removes CO2 naturally. Forest expansion comes with challenges as it is essential not to impact the dynamics of farmland and food supply elsewhere. Modern farming methods can also prolong the time carbon remains stored in soil.

- Direct air capture is the process of capturing CO2 from the air and storing it permanently, either underground or in long-lived products like concrete.

The effectiveness of these methods is typically measured based on whether they can deliver carbon removal at the scale and speed needed.

When it comes to carbon removal projects, durability is a critical consideration. The durability of a project describes how long the carbon dioxide will be kept from the atmosphere.

Short-term durability is up to 100 years, medium-term is 100 to 1,000 years, and long-term is more than 1,000 years.

- Solutions that rely on Earth’s natural carbon cycle have short-term durability measured in decades. For example, forestry projects have a durability of 40 to 100 years.

- Engineered solutions such as direct air capture often have long-term durability measured in millennia. For example, direct air capture has a durability of 10,000 years.

- Long-term projects are typically orders of magnitude more expensive than short-term projects. Once emitted, carbon remains in the atmosphere for 5,000 years. To be considered net zero, carbon that has been emitted needs to be permanently removed.

A short-term carbon removal project will only remove carbon for 100 years, after which it is back in the atmosphere warming up our planet. This is one of the reasons why abatement is preferred to neutralisation. Never releasing carbon is far better than releasing carbon and then trying to keep it out of the atmosphere for 5,000 years.

Climate commitments

There are many different emissions reduction strategies that an organisation can commit to, from carbon neutral to net zero. Understanding the different meanings and implications of each one and finding out which are used by the facilities you use helps you understand how your use of HPC fits within wider climate goals.

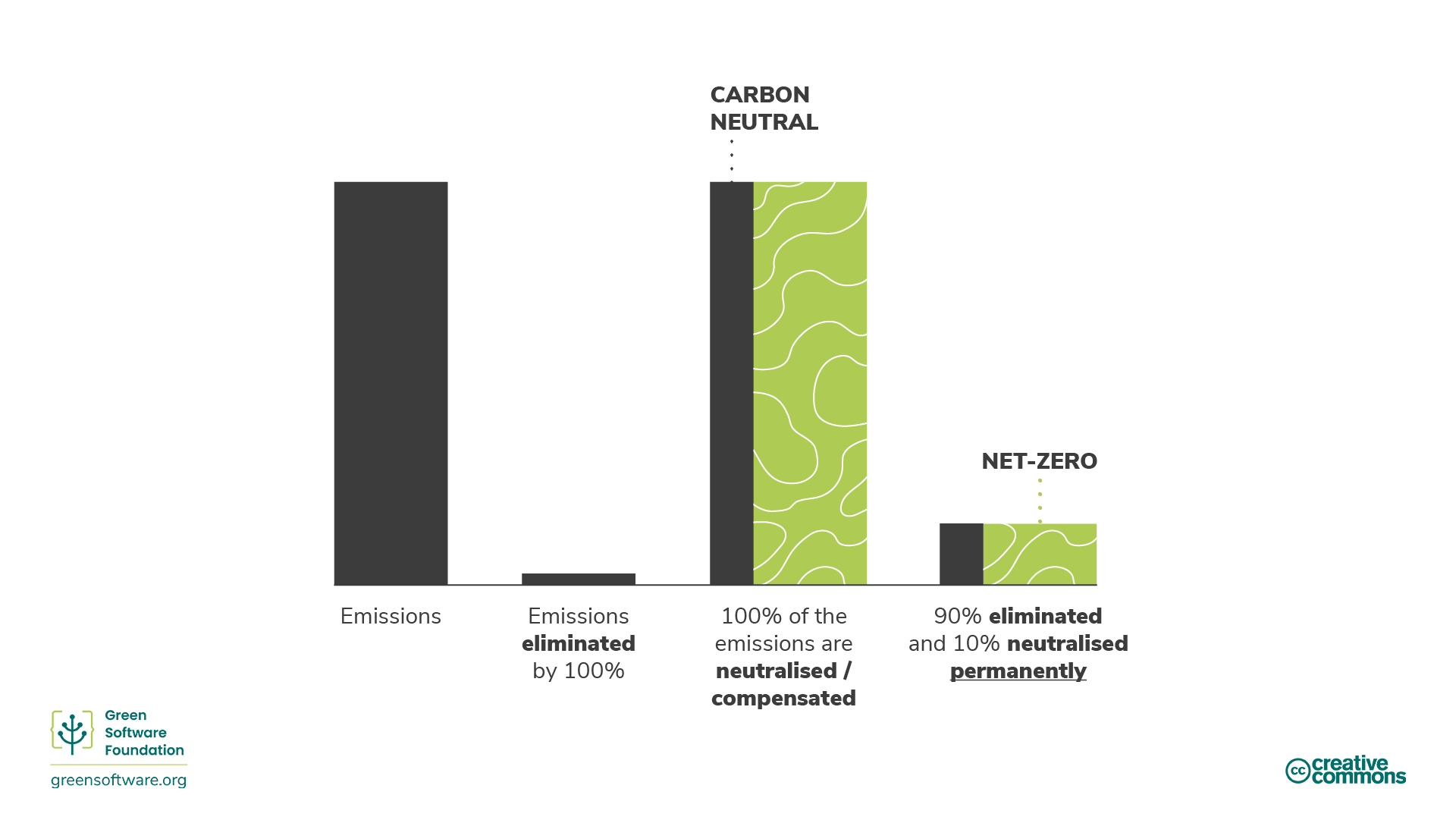

Carbon Neutral

To achieve carbon neutrality, an organisation must measure its emissions, then match the total to its emissions offsets through carbon reduction projects. This can include carbon removal projects (neutralisations) and carbon avoidance projects (compensations).

Carbon neutrality is defined by an internationally recognized standard: PAS 2060. Although this does recommend an organisation sets abatement targets, it does not demand they reduce their emissions. So to be considered carbon neutral, an organisation can just measure and offset without investing resources in eliminating their carbon emissions.

To be carbon neutral, you must cover direct emissions (scope 1 and 2). The general expectation is that organisations measure and offset their scopes 1 and 2, and business travel from scope 3. However, there is no specific requirement to include that.

Carbon neutral is a significant first step for any organisation since it encourages measurement. However, there are not enough carbon offsets in the world to offset the emissions of all the organisations. Therefore, any strategy that does not include abatement will not scale or help the world achieve the 1.5°C target set by the Paris Climate Agreement. This is where net zero comes into play.

Net Zero

Net zero means reducing emissions according to the latest climate science and balancing remaining residual emissions through carbon removals (neutralisations). Net zero, by definition, requires emissions reductions in line with a 1.5°C pathway. All organisations must do this to achieve net-zero global emissions by 2050.

The crucial difference between net zero and carbon neutral is that net zero focuses on abatement rather than neutralisations and compensations. A net-zero target aims to eliminate emissions and only to use offsetting for the residual emissions that you cannot eliminate

The standard for net zero is being developed by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi). They calculate that there is a 66% probability of limiting global warming to 1.5°C if we reach a level of abatement of about 90% of all GHG emissions by mid-century. So, to meet a net-zero target, an organisation needs to eliminate 90% of its emissions by 2050. The remaining emissions can only be offset using neutralisations and permanent carbon removals.

A net-zero strategy would mean that the actual amount of carbon in the atmosphere remains constant.

Also, to be a net-zero target, you must cover direct and indirect, i.e. supply chain emissions (scopes 1,2 and 3). This is significant since scope 3 often represents the majority of emissions.

Fo HPC facilities, part of these strategies include educating and putting policies and approaches in place to support users to understand and take action to reduce their emissions and maximise the carbon efficiency of their HPC use.

HPC-CI as part of a Net-Zero strategy

The HPC-CI is a metric specifically designed to drive the elimination of emissions. The only way to reduce your rate is to invest time and resources into actions that eliminate emissions. The only activities the HPC-CI recognises as elimination actions are making your use of HPC systems more energy efficient, more hardware efficient, or consuming lower-carbon energy sources. Offsets are an essential component of any climate strategy; however, offsets are not eliminations and therefore are not included in the HPC-CI metric.

Any net-zero strategy needs to have plans for how to both eliminate as well as neutralise emissions. The HPC-CI helps organisations and users drive the elimination of emissions due to HPC system use. This makes the HPC-CI a useful component of any net-zero strategy for operation and use of HPC systems.

How can the HPC-CI rate be reduced?

We have mentioned above how the HPC-CI metric is designed to drive abatement of emissions but how can users of HPC systems, operators of HPC systems and organisations that procure HPC systems actually improve the HPC-CI metric? We try to answer this question in this section but it is worth nothing that action is required by all of these parties to reduce emissions from HPC systems.

Reduction in consumption of HPC

While we cover strategies for reducing emissions from a roughly constant amount of HPC use or HPC provision it is clear that a key part (possibly the most important part) of reduction of emissions from HPC use is a reduction in the consumption and provision of HPC. At a fundamental level we need to reduce the amount of compute we are using and the amount of compute hardware we are buying.

“We seem to need reminding that computing is not exempt from having to drastically reduce emissions. Instead of assuming computing can innovate the path to a greater future, the bravest and most heroic action the computing sector could take is to show restraint and leadership, …”

Bran Knowles et al. Our House Is On Fire: The climate emergency and computing’s responsibility.

Users of HPC systems

Before we delve into different approaches for different components of

the HPC-CI equation, there is a high level consideration that can reduce

both the E and M terms in the HPC-CI equation

simultaneously:

Ensure any use of HPC is useful - this sounds obvious but most HPC users will have had the experience of running jobs on HPC systems which consume resources but do not produce useful output due to errors in the software, the input parameters or even the script that runs the job. To improve the HPC-CI rate:

- Ensure that the jobs you are running will produce useful/significant output even if they run correctly - do not run calculations and jobs without a clear understanding of what they add to the research project.

- Carefully test input files and job scripts with small or short jobs before running at large scale to reduce the likelihood of wasted emissions.

- Consider if you can achieve the same project goals with fewer jobs or calculations. For example, optimise the sampling choices when exploring parameter spaces.

Similarly, for people involved in operating and procuring HPC systems, they need to work to ensure that users on the system have the best opportunity to do useful work and reduce wastage, for example by high quality documentation and training and a service design that supports users in making the most of their resources.

Other strategies for improving the HPC-CI metric and thus reducing emissions depend on whether the dominant component is operational emissions (i.e. emissions from energy use) or the embodied emissions. If the components are evenly balanced then you should look at options from both sections.

Operational emissions dominate:

- Improve the energy efficiency of your use - this may involve power

or frequency capping of the hardware you are using. (This improves the

ratio of

EtoRin the HPC-CI equation.) - Temporal shifting - run when carbon intensity is lower. (Reduces

CI.) - Spatial shifting - run on a system where carbon intensity is lower,

run on hardware which has better energy efficiency for your use case,

e.g. GPU may be more energy efficient for your use. (Reduces

CI, or improves the ratio ofEtoR.) - Run fewer calculations or jobs. (Reduces

EandM.)

Embodied emissions dominate:

- Improve the performance of your use - more output per unit of time

(even at the expense of energy efficiency through removing any power).

(improves the ratio of

MtoR.) - Spatial shifting - run on a system which has lower embodied

emissions rate for your use. (Reduces

M.) - Run fewer calculations or jobs. (Reduces

EandM.)

Operators and procuring HPC systems

For operators of HPC systems and organisations that are procuring HPC systems, many of the strategies above have equivalents. In all cases, evaluation of the emissions of the system must be taken into account as a core part of HPC system procurement and operations. It is also critical that emissions information is made available to users to allow them to compute metrics such as the HPC-CI rate to allow them to work to reduce emissions from their use of HPC systems.

Operational emissions dominate:

- Improve the energy efficiency of your HPC systems - this may involve

power or frequency capping of the hardware you are providing or

purchasing hardware that is more energy efficient for the system use

cases. (Improves the ratio of

EtoR.) - Ensure that the power and cooling plant are as efficient as possible

to minimise overheads. (Reduces

E.) - Enable temporal shifting (either automatically or user controlled) -

for example, run workloads with higher power intensities at times when

carbon intensity is lower. (Reduces

CI.) - Spatial shifting - site HPC systems in locations that have the

lowest carbon intensities. (Reduces

CI.)

Embodied emissions dominate:

- Work with users to improve the performance of jobs on the service - more output per unit of time (even at the expense of energy efficiency through removing any power).

- Extend the lifetime of the service as long as possible to extract maximum value from the emissions already in the atmosphere from purchase of the HPC system.

- Purchase HPC systems that have the best ratio of embodied emissions to performance for the workloads that will be run.

- There are a number of methodologies commonly applied to help in the overall fight against climate change. These fall into the general categories of carbon elimination (also known as “abatement”), carbon avoidance (a.k.a. “compensating”), or carbon removal (a.k.a. “neutralising”).

- Abatement is the most effective way to fight climate change although complete carbon elimination is not possible.

- Compensating includes the adoption of renewable energy sources, sustainable living practices, recycling, planting trees, etc.

- Neutralisations refer to the removal and permanent storage of atmospheric carbon to counterbalance the effect of releasing CO2 into the atmosphere. Neutralisations tend to remove the carbon from the atmosphere in the short- and medium-term.

- Net zero aims to eliminate emissions and only offset the residual emissions that cannot be eliminated to reach the 1.5°C target set by the Paris Climate Agreement.

- Which strategies users or HPC system operators prioritise to reduce emissions depends on if the operational or embodied emissions dominate.

- A key part of reducing emissions from HPC use is reducing our consumption of HPC resources.