Energy Efficiency

Last updated on 2025-09-15 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What are low carbon sources of electricity generation?

- How do we quantify energy efficiency?

- What aspects should we consider when looking at energy efficiency of HPC system use?

Objectives

- Understand how different ways of generating electricity lead to different carbon emission rates.

- Understand key concepts in improving energy efficiency of HPC system use.

- Appreciate how the different bounds on HPC application performance impact energy efficiency.

Introduction

Energy is the ability to do work. There are many different forms of energy, such as heat, electrical and chemical, and one type of energy can be converted to another. For example, we convert chemical energy in coal to heat energy, which drives a turbine to generate electrical energy. In other words, electricity is secondary energy converted from another energy type. In this way, we can think of energy as a measure of the electricity used.

All software - from large scale modelling and simulation on HPC systems, to the training of AI models, to the applications running on mobile phones - consumes electricity. One of the best ways to reduce electricity consumption and the subsequent carbon emissions made by software is to make our use of HPC facilities more energy efficient.

The reduction of energy consumed by work on an HPC system depends on a lot of things, including:

- the design and algorithm choices of the software engineers who wrote the software;

- the technology of the HPC system itself;

- how the source code is interpreted by compilers to produce machine-executable code (including compiler optimisations);

- the input and setup of the software given by the user themselves.

All of the people involved at different stages can impact the energy efficiency of use of the HPC system. Some people will only be able to impact one aspect but many people are involved in more than one of these aspects. For example, most researchers using HPC systems make use of software (specifying inputs and specifying the parallel distribution of work) and also design and write their own software (even if this is analysis scripts in a language such as Python).

Collectively, we must all take responsibility for the energy consumed by HPC systems. We should design both them and the software that runs on them, and then use the software on them to consume as little energy as possible. We should make sure that, at every step in the process, there is as little wasted energy as possible.

Let us take a look at some of these concepts and some ways that you can become more energy efficient at every stage.

Key concepts

Fossil fuels and high-carbon sources of energy

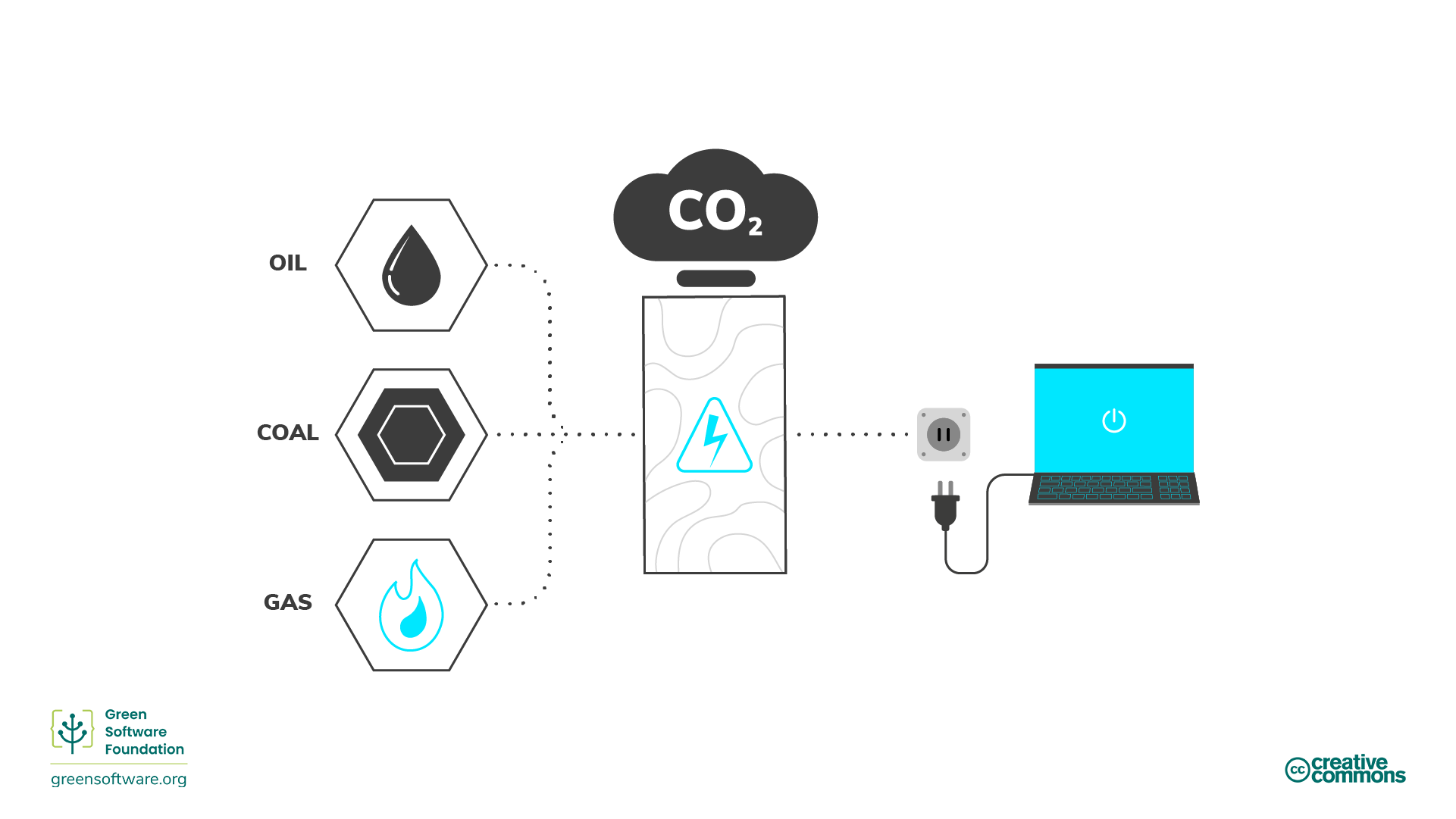

Across the world, a lot of electricity is produced through burning fossil fuels, usually coal or gas. Fossil fuels are made from decomposing plants and animals. These fuels are found in the Earth’s crust and contain carbon and hydrogen, which can be burned for energy. Coal, oil, and natural gas are examples of fossil fuels.

Most people think electricity is clean. Our hands do not get dirty when we plug something into a wall, and our laptops do not need exhaust pipes. However, in some geographical regions most electricity comes from burning fossil fuels and energy supply is the single most significant cause of carbon emissions. For HPC services hosted in such locations, we can draw a direct line from electricity to carbon emissions and, hence, electricity can be considered a proxy for carbon. If our goal is to be carbon efficient in our use of HPC hosted in these regions, then it means our goal is also to be energy efficient since energy is a proxy for carbon. This means using the least amount of energy possible per unit of work.

In the UK (where ARCHER2 is housed), GHG emissions from energy generation make up a much smaller proportion of emissions - 11.5% of total UK emissions in 2023. This is the 5th largest component of UK emissions that year, behind domestic transport (29%), buildings and product use (20%), industry (15%) and agriculture (12%). The emissions from electricity generation have dropped by over 78% from 1990 to 2023. (Data from UK Government: 2023 UK greenhouse gas emissions, provisional figures.) In locations where electricity generation is decarbonising so quickly, measuring electricity use from our use of HPC and using it as a proxy for carbon does not make as much sense as for regions where electricity generation has a large component generated by burning fossil fuels. Reducing electricity use is still part of the goal of greener use of HPC but other (embodied) sources of emissions become more important. We will discuss this later in this workshop.

UK reduced emissions driven by electricity generation changes

“Between 1990 and 2023, UK territorial carbon dioxide emissions decreased by 49.8%, and total greenhouse gas emissions by 52.7%. The largest factor behind this long-term decrease was the change in the mix of fuels being used for electricity generation, with a shift away first from coal to gas in the 1990s, and more recently to renewable energy sources. This was combined with lower electricity demand, owing to greater efficiency resulting from improvements in technology and a decline in the relative importance of energy intensive industries. Overall inland energy consumption is provisionally estimated to have decreased by 24.1% since 1990…”

From: 2023 UK greenhouse gas emissions, provisional figures

While there is still a lot of work to be done on decarbonising the UK electricity grid it is clear that further reductions in UK carbon emissions increasingly need to focus on other sources of carbon emissions.

Low-carbon sources of energy

Clean energy comes from renewable, zero-emission sources that do not pollute the atmosphere when used and save energy through energy-efficient practices. There are overlaps between clean, green, and renewable energy. Here is how we can differentiate between them:

- Clean energy - does not produce carbon emissions e.g. nuclear

- Green energy - sources from nature

- Renewable energy - sources will not expire e.g. solar, wind

Energy measurement

- Energy is measured in joules (J), the SI unit of energy.

- Power is measured in watts, where 1 watt (W) is a rate corresponding to one joule per second.

- A kilowatt (kW) is, therefore, also a rate corresponding to 1000 joules per second.

- A kilowatt-hour (kWh) is an alternative measure of energy (that is commonly used instead of J) corresponding to one kilowatt of power sustained for one hour.

Factors that impact energy efficiency

Now that we know how energy is produced and the associated cost in terms of emissions, based on whether low- or high-carbon energy sources are used. There are other concepts associated with operating HPC services that impact how much energy is used and so our energy efficiency. In particular, power usage effectiveness (PUE) and energy proportionality.

Power usage effectiveness

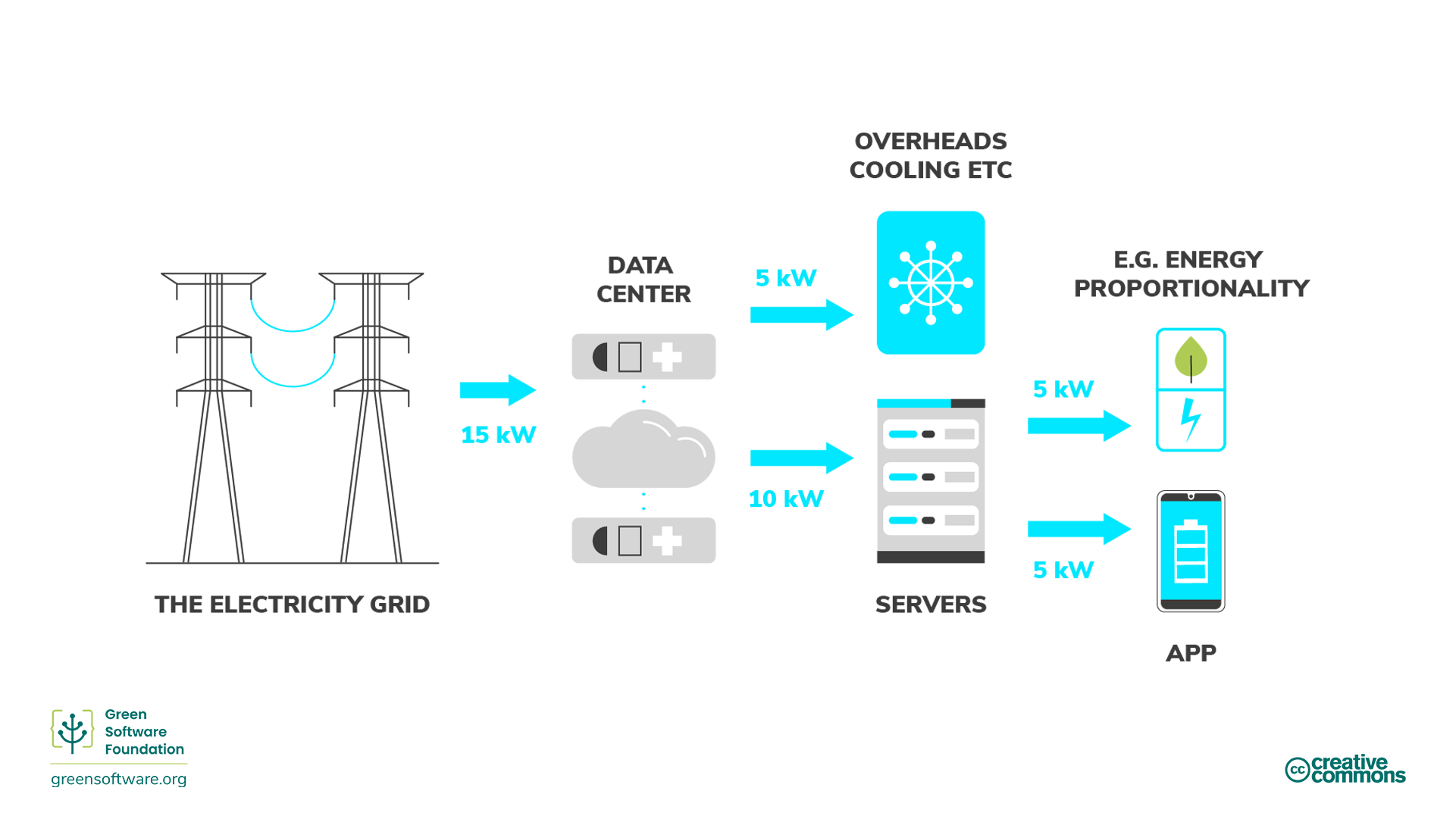

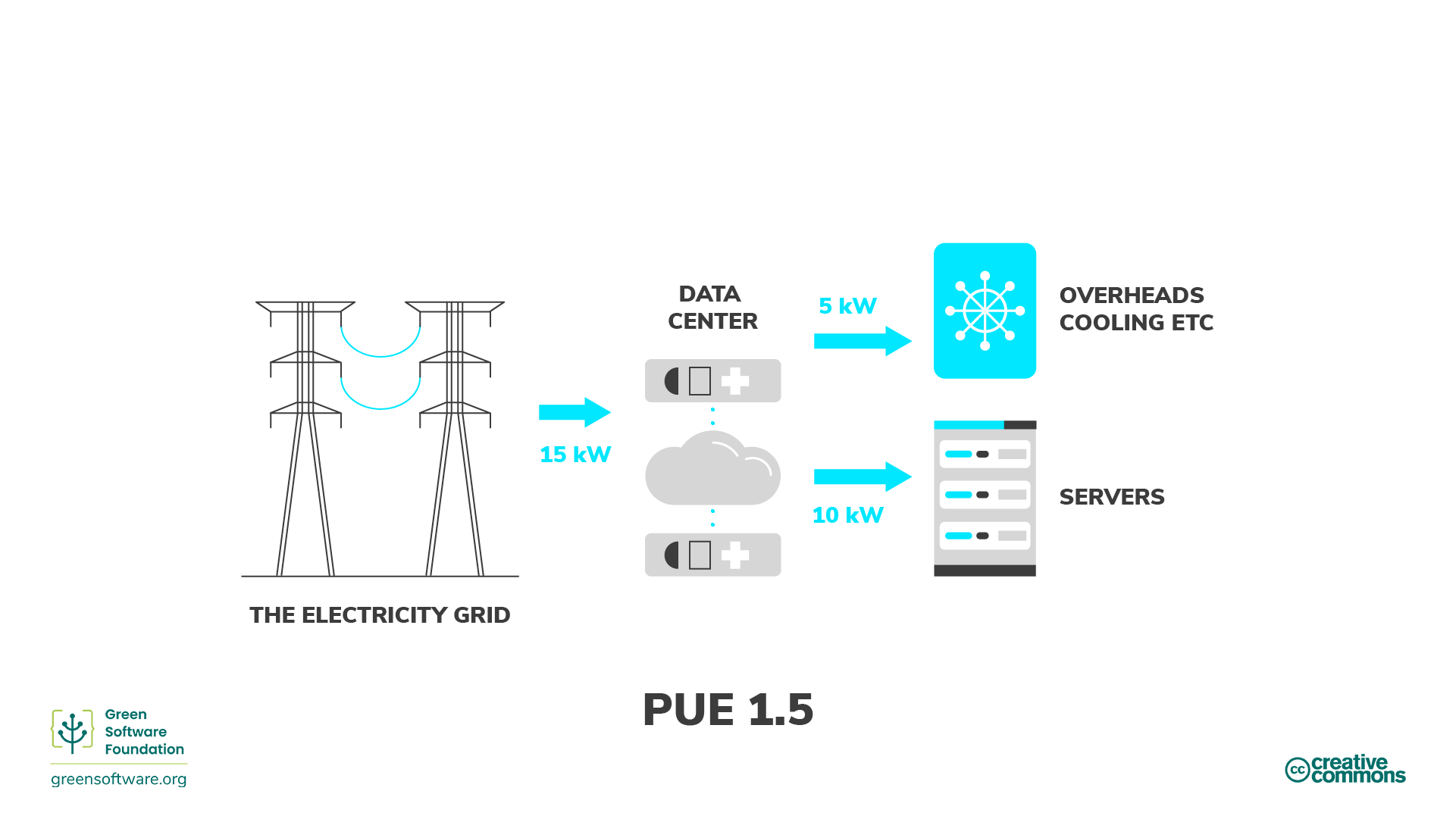

The data centre industry uses the power usage effectiveness (PUE) metric, developed by Green Grid in 2006, to measure data centre energy efficiency. Specifically, this relates to how much energy the computing equipment uses as compared to cooling and other overheads supporting the equipment. When a data center’s PUE is close to 1.0, computing is using nearly all energy. When the PUE is 2.0, this means an additional watt of power is required to cool and distribute power to the HPC equipment for every watt of computing power it uses.

Another way to think of PUE is as a multiplier to your energy consumption when using HPC. So, for example, if your use consumed 10 kWh and the PUE of the data center where it is running is 1.5, then the actual consumption from the grid is 15 kWh: 5kWh goes towards the operational overhead of the data center, and 10 kWh goes to the servers that are running your application.

In many cases, PUE is not constant over time for the data centres that host HPC systems. The PUE value often depends on how much energy is required to cool the system. This obviously varies with load (as the more work a system is doing, the more power it is drawing and the more cooling it requires) but it often also varies with atmospheric conditions - the cooler the air temperature is, the less additional power you need to draw to cool the HPC system. HPC systems hosted in cooler locations can often make use of “free cooling” where refrigeration technology is not required to cool the system, the outside air (or water) temperature is cool enough to do this without the need for mechanical cooling.

ARCHER2 PUE

The PUE of the Advanced Data Centre (ACF) facility that hosts the ARCHER2 system in Edinburgh typically has a PUE of 1.1 as measured over a calendar year. As the ACF is situated in Scotland where air temperatures are cool, it benefits from free cooling for a large proportion of the year.

Energy proportionality

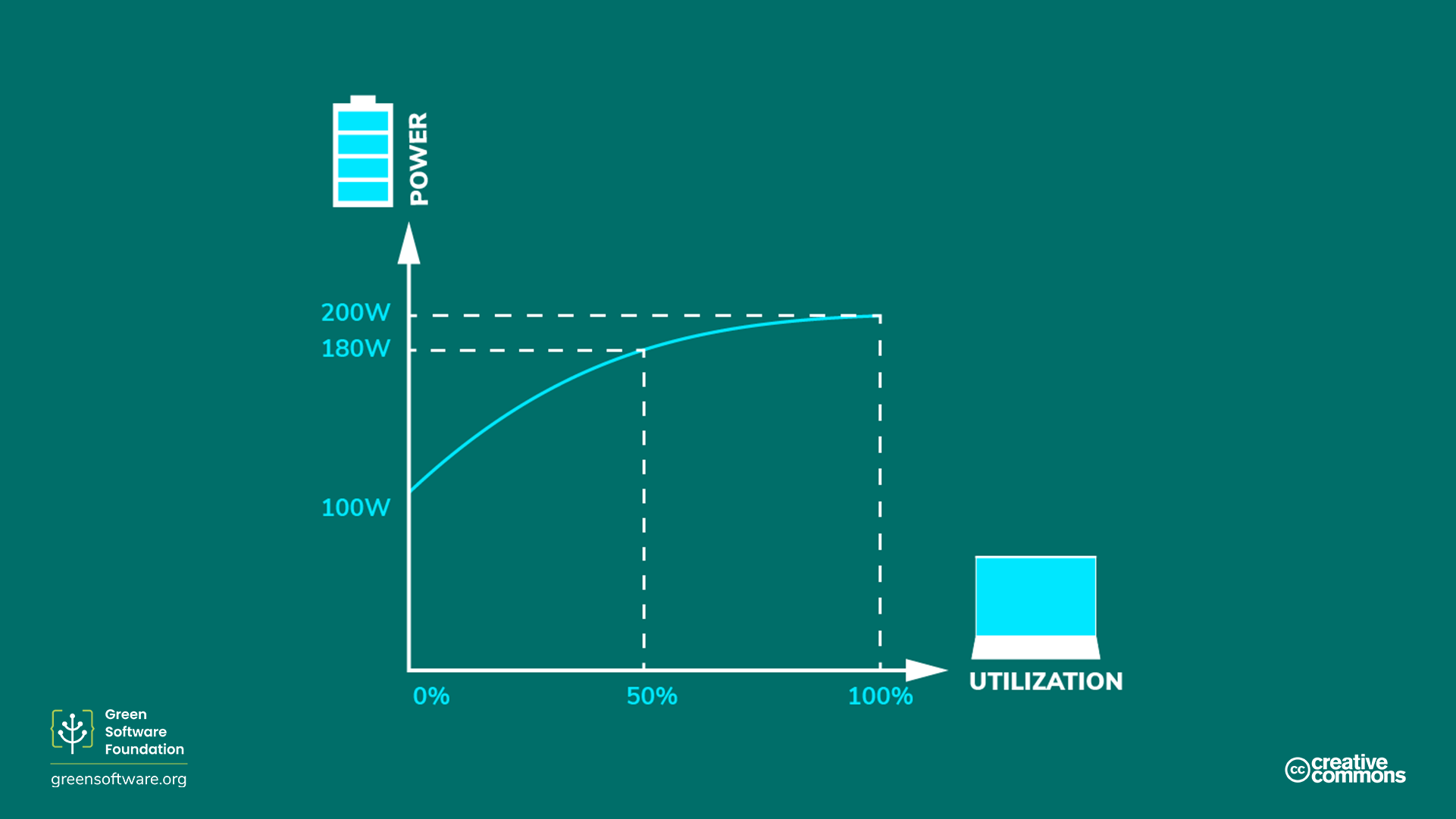

Energy proportionality, first proposed in 2007 by engineers at Google, measures the relationship between power consumed by a computer and the rate at which useful work is done (its utilisation).

Utilisation measures how much of a computer’s resources are used, usually given as a percentage. A fully utilised computer running at its maximum capacity has a high percentage, while an idle computer with no utilisation has a lower percentage.

The relationship between power and utilisation is not linearly proportional. Mathematically speaking, linear proportionality between two variables means their ratios are equivalent. As an example of the nonlinear relationship between utilisation and power draw, at 0% utilisation, a computer may draw 100 W; at 50%, it draws 180 W; and at 100%, it draws 200 W. The relationship between power consumption and utilisation is not linear and does not cross the origin.

Because of this, the more we utilise a computer, the more efficient it becomes at converting electricity to practical computing operations. One way to improve hardware efficiency is to run the workload on as few servers as possible, with the servers running at the highest utilisation rate, maximising energy efficiency.

Usage efficiency in HPC systems

However, the story for HPC use is actually less straightforward than this description. The energy proportionality argument holds when the performance of an application is compute-bound - that is, when the output from the application you are running is strongly correlated with the performance of the processors. The performance of many HPC applications is actually memory-bound so the performance is dependent on the performance of data moving from memory to be processed. In these cases, once you are above a certain performance threshold for the floating point units any additional power draw does not lead to increased utilisation (i.e. useful performance for the application); the more you you utilise the processor, the more power you draw but you do not get any additional useful performance so this is just wasted electricity, reducing the energy efficiency of your use. It becomes even more complex as you run parallel applications (as typically happens on HPC resources) as the change in parallel distribution can change the balance between compute-bound and memory-bound performance for your application; meaning that you may need to choose different strategies to maximise energy efficiency at different parallelisations even for the same problem and software.

HPC application performance

Performance of HPC applications can be compute-bound, memory-bound, IO-bound, or communications-bound; and the utilisation argument made above only really applies to applications where performance is strongly compute-bound. In reality, the performance of most HPC applications is bound by different limits at different stages in their execution (e.g. IO-bound while reading in large datasets, compute-bound while calculating) and so a theoretical analysis of how the energy consumption changes as a function of processor utilisation is difficult to perform.

Static power draw

The static power draw of a computer is how much electricity is drawn when in an idle state. The static power draw varies by configuration and hardware components, but all parts have some static power draw. This is one of the reasons that PCs, laptops, and end-user devices have power-saving modes. If the device is idle, it will eventually trigger a hibernation mode and put the disk and screen to sleep or even change the CPU’s frequency. These power-saving modes save on electricity, but they have other trade-offs, such as a slower restart when the device wakes up.

HPC systems are usually not configured for aggressive or even minimal power saving when idle. Many use cases running on servers demand total capacity as quickly as possible because the server needs to respond to rapidly changing demands, which leads to many servers in idle modes during low-demand periods. An idle server has a carbon cost from both the embedded carbon as well as its inefficient utilisation. This is one reason why the goal of many HPC systems is to maximise utilisation.

Practical advice

Given this complexity, what practical steps can you take to decide on how to run in an energy-efficient manner on HPC systems? The answer is to run some test cases and measure the energy consumption and performance, then change parameters (such as processor power cap, or number of parallel processes) and measure again to see what the impact is on both performance and energy consumption. Using a benchmarking approach such as this, you can practically improve the energy efficiency of your use of HPC.

If you happen to be a developer of the software you are using then you may also be able to change the algorithms, data layout and other aspects of the software to improve energy efficiency. Such approaches are beyond the scope of this workshop but benchmarking energy consumption also form a core component of this work.

Exercise: Energy efficiency on HPC systems

An application (GROMACS) running on ARCHER2 has the following performance characteristics and energy use at different node counts and different CPU frequency settings. What are the most energy efficient combinations in kWh/ns of node count and CPU frequency for these types of calculations? Which is the worst, and how large is the percentage difference between the best and worst cases?

| 2.0 GHz | 2.25 GHz + boost | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node count | ns simulated | Runtime (s) | kWh | Runtime (s) | kWh |

| 1 | 0.020 | 369 | 0.0464 | 288 | 0.0464 |

| 2 | 0.020 | 198 | 0.0450 | 156 | 0.0465 |

| 3 | 0.020 | 155 | 0.0438 | 109 | 0.0465 |

| 4 | 0.020 | 117 | 0.0471 | 93 | 0.0513 |

We can compute the energy efficiency in kWh/ns by dividing the energy used by the number of ns simulated:

| 2.0 GHz | 2.25 GHz + boost | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node count | ns simulated | Runtime (s) | kWh/ns | Runtime (s) | kWh/ns |

| 1 | 0.020 | 369 | 2.32 | 288 | 2.32 |

| 2 | 0.020 | 198 | 2.25 | 156 | 2.32 |

| 3 | 0.020 | 155 | 2.19 | 109 | 2.32 |

| 4 | 0.020 | 117 | 2.36 | 93 | 2.56 |

So, the most energy efficient combination is 3 nodes at 2 GHz CPU clock frequency and the worst is 4 nodes with 2.25 GHz + boost CPU clock frequency. The worst case is around 17% less energy efficient than the best case. While this difference may not amount to much energy for a single run, if hundreds or thousands of simulations are run as part of a project this can lead to a significant reduction in consumed energy.

- In regions where electricity production is dominated by burning fossil fuels, electricity is a good proxy for carbon, so using HPC in an energy efficient way is equivalent to using HPC in a way that is carbon efficient.

- In regions of where electricity production is dominated by low carbon energy sources, electricity is not a good proxy for carbon.

- Green HPC use takes responsibility for its electricity consumption and considers how this relates to carbon emissions.

- Quantifying the energy consumption of your HPC use is a step in the right direction to start thinking about how you can operate more efficiently. However, understanding the energy consumption of your use of HPC is not the only story. The hardware your software is running on uses some of the electricity for operational overhead. This can be estimated through the power usage efficiency (PUE) metric for HPC systems (and for computing resources hosted in data centres more generally).

- How you go about improving the energy efficiency of use of an HPC system depends on the software you are using and the input parameters as well as the hardware.

- Often, the only practical way forward in the face of this complexity is to perform some benchmarking to assess how energy efficiency can be improved.