Being FAIR

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How can you get more value from your own data?

What are the FAIR guidelines?

Why does being FAIR matter?

Objectives

Recognise typical issues that prevent data re-use

Understand FAIR principles

Know steps for achieving FAIR data

(5 min teaching)

We have seen how early adoption of good research data management practices can benefit your team and institution. The wide adoption of Open Access principles has resulted in access to recent biomedical publications becoming far easier. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said about research data and software that accompanies such publications.

What is research data?

“Research data are collected, observed or generated for the purpose of analysis, to produce and validate original research results… [ie] whatever is necessary to verify or reproduce research findings, or to gain a richer understanding of them” Research Data MANTRA - Research data in context, University of Edinburgh

Although scientific data comes in all shapes and sizes, we still encounter groups who (wrongly) believe they do not have data! Data does not mean only Excel files with recorded measurements from a machine. Data also includes:

- images, not only from microscopes

- information about biological materials, like strain or patient details

- recipes, laboratory and measurement protocols

- scripts, analysis procedures, and custom software can also be considered data However, there are specific recommendations on how to deal with code.

Let’s have a look how challenging it can be to access and use data from published biological papers.

Exercise 1a: Impossible protocol (5 + 3 min)

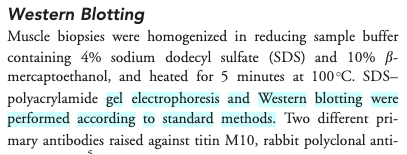

You need to do a western blot to identify Titin proteins, the largest proteins in the body, with a molecular weight of 3,800 kDa. You found a Titin-specific antibody sold by Sigma Aldrich that has been validated in western blots and immunofluorescence (‘SAB1400284’). Sigma Aldrich lists the Yu et al., 2019 paper as reference.

Find details of how to separate and transfer this large protein in the reference paper.

- Hint 1: Methods section has a Western blot analysis subsection.

- Hint 2: Follow the references.

Would you say that the methods was Findable? Accessible? Reusable?

Solution

- Ref 17 will lead you to this paper, which first of all is not Open Access. Which not only means that some users won’t be able to read it, but even those that can access it will still be subject to restrictions on sharing content from it.

- Access the paper if you can (you may need to login to an institutional account) and find the ‘Western Blotting’ protocol on page 232 which will show the following (Screenshot from the methods section from Evilä et al 2014):

- The paper says “..Western blotting [was] performed according to standard methods.” - with no further reference to these standard methods, describing these methods, nor supplementary material detailing these methods.

- This methodology is unfortunately a true dead end and we thus can’t easily continue our experiments!

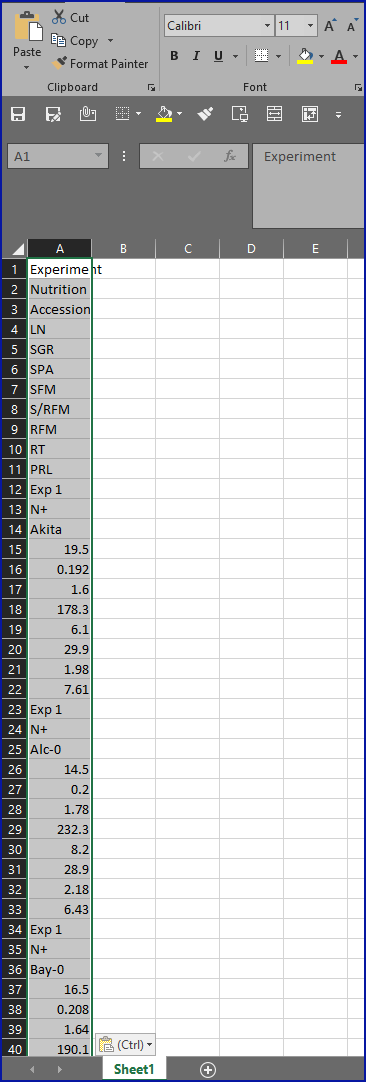

Exercise 1b: Impossible average

Ikram 2014 paper contains data about various metabolites in different accessions (genotypes) of Arabidopsis plant. You would like to calculate average nitrogen content in plants grown under normal and nitrogen limited conditions. Please calculate the average (over genotypes) nitrogen content for the two experimental conditions.

- Hint 1. Data are in Supplementary data

- Hint 2. Search for nitrogen in paper text to identify the correct data column.

Solution

- Download the supplementary data zip file.

- Open the PDF file.

- Copy and paste the data one page at a time.

- Whether trying to import the data to CSV, Excel, R, python or any other statistical package, this source is in an incredibly inconvenient format, as you can see in this screenshot showing what happened when we tried to copy-and-paste the data into Excel:

Exercise 1c: Impossible numbers

Systems biologists usually require raw numerical data to build their models. Take a look at the following example: Try to find the numerical data behind the graph shown underneath the photo of the blots in Figure 6A of Sharrock RA and Clack T, 2002 , which demonstrates changes in levels of phytochrome proteins.

- Hint 1: The ‘Materials and methods’ section describes the quantification procedure

- Hint 2: ‘Supporting Information’ or ‘Supplementary Materials’ sections often contain data files.

- Hint 3: It is considered good practice for papers to include a ‘Data Availability’ statement.

Solution

How easy was it? :-)

It appears the authors have not made the figures available anywhere, not even hidden in a supplementary information section.

Help your readers by depositing your data in an archive and including a Data Availability statement containing the data DOI in your papers!

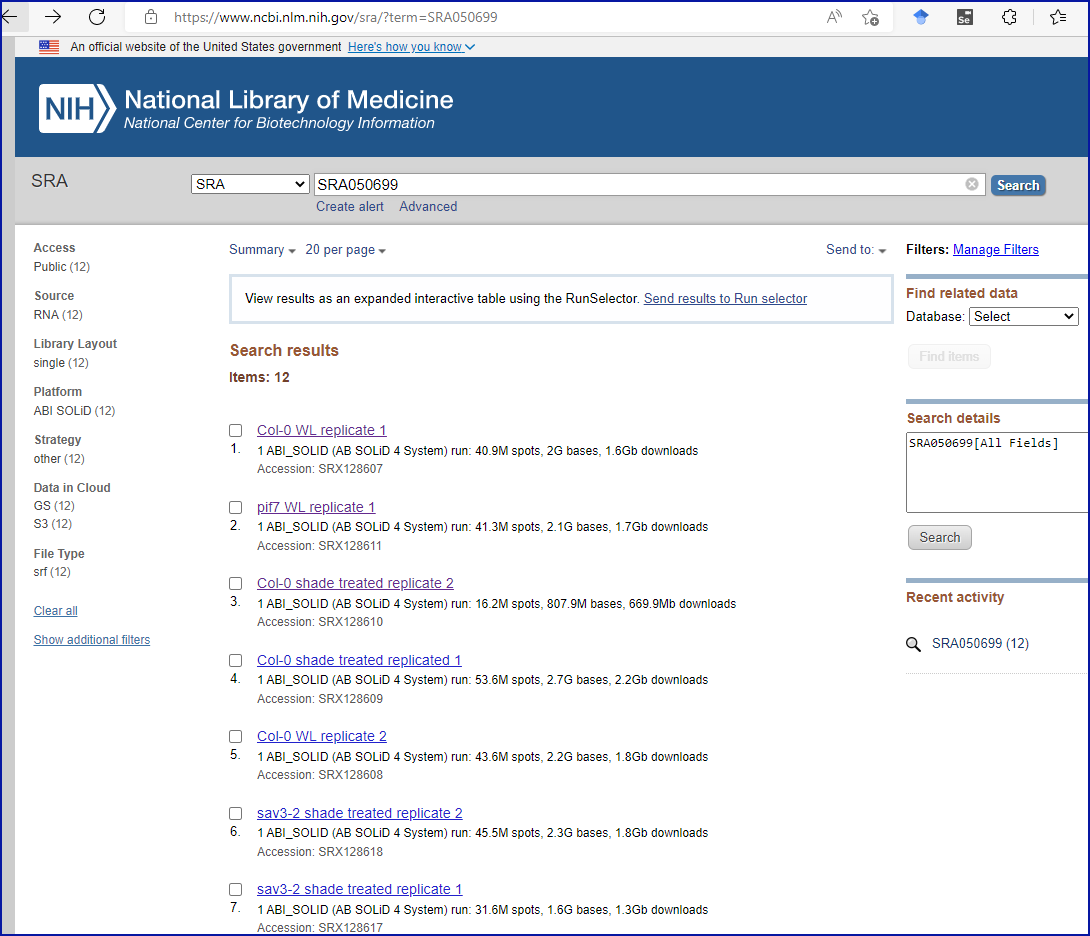

Exercise 1d: Perplexing resource/link

RNA-seq (transcriptomics) data is usually deposited in online repositories such as SRA - Sequence Read Archive or ArrayExpress within the EBI’s BioStudies database.

Your task is to find the link to the repository containing the raw RNA-seq data described in Li et al., Genes Dev. 2012. Can you find it anywhere?

- Hint: Try Ctrl + F to use your browser’s search function to search for the word ‘data’.

Solution

Puzzlingly, the authors have chosen to include the SRA accession number in the final sentence of the ‘Acknowledgments’ section. Perplexingly, searching the SRA website with the accession number brings back twelve results at the time of writing, none of which contain the cited accession number in them, but they appear to correspond to an experiment with a title and institutional affiliation which match the journal article, as you can see from this screenshot:

(10 min teaching)

The above examples illustrate the typical challenges in accessing research

data and software.

Firstly, data/protocols/software often do not have an identity

of their own, but only accompany a publication.

Second, they are not easily accessible or reusable; for example, when all the details are inside one ‘supporting information’ PDF file.

Such files sometimes include “printed” numerical tables or even source code, both of which need to be “re-typed” if someone would like to use them. Data are shared in proprietary file formats specific to a particular vendor and not accessible if one does not have a particular software package that accompanies the equipment the authors used. Finally, data files are often provided without any detailed description

other than the whole article text.

In our examples, the protocol was difficult to find (the loops), difficult to access (pay wall), and not reusable as it lacked the necessary details (dead-end).

In exercise 1b, the data were not interoperable or reusable as they were only available as a figure graph.

The FAIR principles help us to avoid such problems.

From SangyaPundir

From SangyaPundir

FAIR Principles

In 2016, the FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship were published in Scientific Data. The original guidelines focused on “machine-actionability” - the ability of computer systems to operate on data with minimal human intervention. However, now the focus has shifted to making data accessible from a human perspective, and not an automated one (mostly due to the lack of user friendly tools that could help deal with standards and structured metadata).

Findable: It should be easy for both humans and computers to find data and metadata. Automatic and reliable discovery of datasets and services depends on machine-readable persistent identifiers (PIDs) and metadata.

Accessible: (Meta)data should be retrievable by their identifiers using a standardised and open communications protocol (including authentication and authorisation). Metadata should be available even when the data are no longer available.

Interoperable: Data should be able to be combined with and used with other data or tools. The format of the data should be open and interpretable for various tools. This principle, just like the others, applies both to data and metadata; (meta)data should use vocabularies that follow FAIR principles.

Re-usable: FAIR aims to optimise the reuse of data. Metadata and data should be well-described so that they can be replicated and/or combined in different settings. The conditions under which reuse of (meta)data is allowed, or the absence of conditions, should be stated with clear and accessible license(s).

What do the components of FAIR mean in (biological) practice?

Findable & Accessible

Deposit data to a trustworthy public repository.

Repositories provide persistent identifiers (PIDs), controlled vocabularies for efficient cataloguing, advanced metadata searching and download statistics. Some repositories can also host supported curation, digital preservation, private data or provide embargo periods, meaning access to all data can be delayed or restricted.

There are general “data agnostic” repositories, such as Zenodo, or domain specific ones, for example UniProt.

We will cover repositories in more detail in a later episode.

What are persistent identifiers (PIDs)?

A persistent identifier is a long-lasting reference to a digital resource. Typically it has two components:

- a service that locates the resource over time even when its location changes

- and a unique identifier (that distinguishes the resource or concept from others).

Persistent identifiers aim to solve the problem of the persistence of accessing cited resource, particularly in the field of academic literature. All too often, web addresses (links) change over time and fail to take you to the referenced resource you expected.

There are several services and technologies (schemes) that provide PIDs for objects (whether digital, physical or abstract). One of the most popular is Digital Object Identifier (DOI), recognisable by the prefix doi.org in the web links. For example: https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 resolves to the location of the paper that describes the FAIR principles.

Public repositories often maintain web addresses of their content in a stable form which follow the convention http://repository.adress/identifier; these are often called permalinks. For well established services, permalinks can be treated as PIDs.

For example: http://identifiers.org/SO:0000167 resolves to a page defining promoter role, and can be used to annotate part of a DNA sequence as performing such a role during transcription.

Interoperable

- Use standard or open file formats (can be domain specific)

- Always use .csv or .xlsx files for numerical data.

- Never share data tables as word or pdf,

- Provide underlying numerical data for all plots and graphs

- Convert proprietary binary formats to the open ones. For example convert Snapgene to Genbank, microscopy multistack images to OME-TIFF

Reusable

- Describe your data well / provide good metadata

- write README file describing the data

- user descriptive column headers for the data tables

- tidy data tables, make them analysis friendly

- provide as many details as possible (prepare good metadata)

- use (meta)data formats (e.g. SBML, SBOL)

- follow Minimum Information Standards

Describing data well is the most challenging part of the data sharing process. This topic is covered in more detail in FAIR in bio practice

- Attach license files.

Licenses explicitly declare conditions and terms by which data and software can be re-used.

Here, we recommend:

- for data Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license,

- for code a permissive open source license such as the MIT, BSD, or Apache license.

Copyright and data (extra details)

Software code (the text) automatically gets the default copyright protection by law, which prevents others from copying or modifying it. By adding an explicit license, you can declare that you permit re-use by others. By removing the need for others to contact you to ask your permission, you not only save everybody time but you also remove a barrier to equality and diversity, since all potential users can see the dataset is available for them (rather than having a situation where unequal social capital and bias, real or perceived, could hamper access).

Data, being factual, cannot be copyrighted. So why, do we need a license?

While the data itself cannot be copyrighted, the way it is presented can be. The extent to which it is protected needs ultimately to be settled by the court.

The “good actors” will refrain from using your data to avoid “court” risks. But the “bad actors” will either ignore the risk or can afford the lawyers’ fees.

Exercise 3: FAIR and You (3 + 2min)

The FAIR acronym is sometimes accompanied with the following labels:

- Findable - Citable

- Accessible - Trackable and countable

- Interoperable - Intelligible

- Reusable - Reproducible

Using those labels as hints discuss how FAIR principles directly benefit you and your team as the data creators.

Solution

- Findable data have their own identity, so they can be easily cited and secure the credits to the authors

- Data accessibility over the Internet using standard protocols can be easily monitored (for example using Google analytics). This results in metrics on data popularity or even geo-locations of data users.

- Interoperable data can benefit the future you, for example you will be able to still read your data even when you no longer have access to the specialized, vendor specific software with which you worked with them before. Also the future you may not remember abbreviations and ad-hoc conventions you used before (Intelligible).

- Well documented data should contain all the details necessary to reproduce the experiments, helping the future you or someone taking over from you in the laboratory.

- Saves time and money.

FAIR vs Open Science (3 min teaching)

FAIR does not mean Open. Actually, FAIR guidelines only require that the metadata record and not necessarily the data is always accessible. For example, the existence of the data can be known (their metadata), the data can have easy to use PID to reference them, but the actual data files may be restricted so as to be downloaded only after login and authorization.

However, if data are already in the FAIR form, i.e. accessible over the internet, in interoperable format and well documented, then it is almost effortless to “open” the dataset and make it available to the whole public. The data owner can do it any time when he no longer perceives opening as a risk.

At the same time, Open data which does not follow FAIR guidelines have little value. If they are not well described, not in open formats then they are not going to be re-used even if they were made “open” by posting them on some website.

Exercise 4: FAIR Quiz (3 min - run through break)

Which of the following statements is true/false (T or F).

- F in FAIR stands for free.

- Only figures presenting results of statistical analysis need underlying numerical data.

- Sharing numerical data as a .pdf in Zenodo is FAIR.

- Sharing numerical data as an Excel file via Github is not FAIR.

- Group website is a good place to share your data.

- Data from failed experiments are not re-usable.

- Data should always be converted to Excel or .csv files in order to be FAIR.

- A DOI of a dataset helps in getting credit.

- FAIR data must be peer reviewed.

- FAIR data must accompany a publication.

Solution

- F in FAIR stands for free. F

- Only figures presenting results of statistical analysis need underlying numerical data. F

- Sharing numerical data as a .pdf in Zenodo is FAIR. F

- Sharing numerical data as an Excel file via Github is not FAIR. F

- Group website is a good place to share your data. F

- Data from failed experiments are not re-usable. F

- Data should always be converted to Excel or .csv files in order to be FAIR. F

- A DOI of a dataset helps in getting credit. TRUE

- FAIR data must be peer reviewed. F

- FAIR data must accompany a publication. F

Key Points

FAIR stands for Findable Accessible Interoperable Reusable

FAIR assures easy reuse of data underlying scientific findings