Content from Reproducible Research

Last updated on 2026-01-30 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What does it mean to be “reproducible”?

- How is “reproducibility” different than “reuse”?

Objectives

- Describe the terms “reproducibility” and “reuse” as they relate to research computing.

- Describe what is needed for a computational environment to be reproducible.

Introduction

Modern scientific analyses are complex software and logistical workflows that may span multiple software environments and require heterogenous software and computing infrastructure. Scientific researchers need to use these tools to be able to do their research, and to ensure the validity of their work, which can be difficult. Scientific software enables all of this work to happen, but software isn’t a static resource — software is continually developed, revised, and released, which can introduce breaking changes or subtle computational differences in outputs and results. Having the software you’re using change without you intending it from day-to-day, run-to-run, or on different machines is problematic when trying to do high quality research. These changes can cause software bugs, errors in scientific results, and make findings unreproducible. All of these things are not desirable!

When discussing “software” in this lesson we will primarily be meaning open source software that is openly developed. However, there are situations in which software might (for good reason) be:

- Closed development with open source release artifacts

- Closed development and closed source with public binary distributions

- Closed development and closed source with proprietary licenses

Challenges to reproducible research?

Take 3 minutes to discuss the following questions in small groups.

What are other challenges to doing reproducible research?

Think about all aspects of research computing — data, hardware, and software — from collecting and cleaning the data through analysis and visualization to publishing your methods and results?

Have you even inherited a project from a previous contributor? Or gone back to a previous project more than couple months later and struggled to get back into it? What issues did you come across?

There are many! Here are some you might have thought of:

- (Not having) Access to data

- Required software packages be removed from mutable package indexes

- Unreproducible builds of software that isn’t packaged and distributed on public package indexes

- Analysis code not being under version control

- Not having any environment definition configuration files

Computational reproducibility

“Reproducible” research can mean many things and is a multipronged problem. This lesson will focus primarily on computational reproducibility. Like all forms of reproducibility, there are multiple “levels” of reproducibility. For this lesson we will focus on “full” reproducibility, meaning that reproducible software environments will:

- Be defined through user readable and writable configuration files.

- Have machine produced “lock files” with a full definition of all software in the environment.

- Specify the target computer platforms (operating system and architecture) for all environments solved.

- Have the resolution of a platform’s environments be machine agnostic (e.g. macOS platform machines can solve environments for Linux platforms).

- Have the software packages defined in the environments be published on immutable public package indexes.

What is computational reproducibility?

Do you think “computational reproducibility” means that the exact same numeric results should be achieved every time? Discuss with your table.

Not necessarily. Even though the computational software environment is identical there are things that can change between runs of software that could slightly change numerical results (e.g. random number generation seeds, file read order, machine entropy). This isn’t necessarily a problem, and in general one should be more concerned with getting answers that make sense within application uncertainties than matching down to machine precision.

Did your the individuals in your group agree?

Computational reproducibility vs. scientific reuse

Aiming for computational reproducibility is the first step to making scientific research more beneficial to us. For the purposes of a single analysis this should be the primary goal. However, just because a software environment is fully reproducible does not mean that the research is automatically reusable. Imagine an analysis that has been fully documented but with use assumptions (e.g. the data used, configuration options) hard-coded into the software. The analysis can be reproduced, but needs to be refactored for different analysis choices.

Reuse allows for the tools and components of the scientific workflow to be composable tools that can interoperate together to create a workflow. The steps of the workflow might exist in radically different computational environments and require different software, or different versions of the same software tools. Given these demands, reproducible computational software environments are a first step towards fully reusable scientific workflows.

This lesson will focus on computational reproducibility of scientific workflows. Scientifically reusable analysis workflows are a more extensive topic, but this lesson will link to references on the topic.

The challenges of creating reproducible and reusable workflows

What personal challenges have you encountered to making your own research practices reproducible and reusable?

- Technical expertise in reproducibility technologies

- Time to learn new tools

- Balancing reproducibility concerns with using tools the entire research team can understand

In addition to the computational issues that arise while creating reproducible and reusable workflows, it takes time and effort to design analyses with these in mind. This lesson aims to teach you tools that will make creating reproducible and reusable workflows easier.

- Modern scientific research is complex and requires software environments.

- Computational reproducibility helps to enable reproducible science.

- New technologies make all of these processes easier.

- Reproducible computational software environments are a first step toward fully reusable scientific workflows.

Content from Introduction to Pixi

Last updated on 2026-01-30 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is Pixi?

- How does Pixi enable fully reproducible software environments?

- What are Pixi’s semantics?

Objectives

- Outline Pixi’s workflow design

- Summarize the relationship between a Pixi manifest and a lock file

- Create a multi-platform and multi-environment Pixi workspace

Pixi

As described in the previous section on computational reproducibility, to have reproducible software environments we need tools that can take high level human writeable environment configuration files and produce machine-readable, digest-level lock files that exactly specify every piece of software that exists in an environment.

Pixi is a cross-platform package and environment manager that can handle complex development workflows. Importantly, Pixi automatically and non-optionally will produce or update a lock file for the software environments defined by the user whenever any actions mutate the environment. Pixi is written in Rust, and leverages the language’s speed and technologies to solve environments fast.

Pixi addresses the concept of computational reproducibility by focusing on a set of main features:

- Virtual environment management: Pixi can create environments that contain conda packages and Python packages and use or switch between environments easily.

-

Package management: Pixi enables the user to

install, update, and remove packages from these environments through the

pixicommand line. - Task management: Pixi has a task runner system built-in, which allows for tasks with custom logic and dependencies on other tasks to be created.

It also combines these features with robust behaviors:

- Automatic lock files: Any changes to a Pixi workspace that can mutate the environments defined in it will automatically and non-optionally result in the Pixi lock file for the workspace being updated. This ensures that any and every state of a Pixi project is trivially computationally reproducible.

- Solving environments for other platforms: Pixi allows the user to solve environment for platforms other than the current user machine’s. This allows for users to solve and share environment to any collaborator with confidence that all environments will work with no additional setup.

- Pairity of conda and Python packages: Pixi allows for conda packages and Python packages to be used together seamlessly, and is unique in its ability to handle overlap in dependencies between them. Pixi will first solve all conda package requirements for the target environment, lock the environment, and then solve all the dependencies of the Python packages for the environment, determine if there are any overlaps with the existing conda environment, and the only install the missing Python dependencies. This ensures allows for fully reproducible solves and for the two package ecosystems to compliment each other rather than potentially cause conflicts.

- Efficient caching: Pixi uses an extremely efficient global caching scheme. This means that the first time a package is installed on a machine with Pixi is the slowest is will ever be to install it for any future project on the machine while the cache is still active.

Project-based workflows

Pixi uses a “project-based” workflow which scopes a workspace and the installed tooling for a project to the project’s directory tree.

Pros

- Environments in the workspace are isolated to the project and can not cause conflicts with any tools or projects outside of the project.

- A high level declarative syntax allows for users to state only what they need, making even complex environments easy to understand and share.

- Environments can be treated as transient and be fully deleted and then rebuilt within seconds without worry about breaking other projects. This allows for much greater freedom of exploration and development without fear.

Cons

- As each project has its own version of its packages installed, and does not share a copy with other projects, the total amount of disk space on a machine can be larger than other forms of development workflows. This can be mitigated for disk limited machines by cleaning environments not in use while keeping their lock files and cleaning the system cache periodically.

- Each project needs to be set up by itself and does not reuse components of previous projects.

Pixi project files and the CLI API basics

Every Pixi project begins with creating a manifest file. A manifest file is a declarative configuration file that list what the high level requirements of a project are. Pixi then takes those requirements and constraints and solves for the full dependency tree.

Let’s create our first Pixi project. First, to have a uniform

directory tree experience, clone the pixi-lesson GitHub

repository (which you made as part of the setup) under your home

directory on your machine and navigate to it.

Then use pixi init to create a new project directory and

initialize a Pixi manifest with your machine’s configuration.

OUTPUT

Created /home/<username>/pixi-lesson/example/pixi.tomlNavigate to the example directory and check the

directory structure

We see that Pixi has setup Git configuration files for the project as

well as a Pixi manifest pixi.toml file. Checking the

default manifest file, we see three TOML tables: workspace,

tasks, and dependencies.

TOML

[workspace]

authors = ["Your Name <your email from your global Git config>"]

channels = ["conda-forge"]

name = "example"

# This will be whatever your machine's platform is

platforms = ["linux-64"]

version = "0.1.0"

[tasks]

[dependencies]-

workspace: Defines metadata and properties for the entire project. -

tasks: Defines tasks for the task runner system to execute from the command line and their dependencies. -

dependencies: Defines the conda package dependencies from thechannelsin yourworkspacetable.

For the rest of the lesson we’ll ignore the authors list

in our discussions as it is optional and will be specific to you.

At the moment there are no dependencies defined in the manifest, so

let’s add Python using the pixi add

CLI API.

OUTPUT

✔ Added python >=3.13.5,<3.14What happened? We saw that python got added, and we can

see that the pixi.toml manifest now contains

python as a dependency

TOML

[workspace]

channels = ["conda-forge"]

name = "example"

# This will be whatever your machine's platform is

platforms = ["linux-64"]

version = "0.1.0"

[tasks]

[dependencies]

python = ">=3.13.5,<3.14"Further, we also now see that a pixi.lock lock file has

been created in the project directory as well as a .pixi/

directory.

The .pixi/ directory contains the installed

environments. We can see that at the moment there is just one

environment named default

Inside the .pixi/envs/default/ directory are all the

libraries, header files, and executables that are needed by the

environment.

The pixi.lock lock file is a YAML file that contains two

definition groups: environments and packages.

The environments group lists every environment in the

workspace for every platform with a complete listing of all packages in

the environment. The packages group lists a full definition

of every package that appears in the environments lists,

including the package’s URL on the conda package index and digests

(e.g. sha256, md5).

Here’s an example of what the environments and

packages groups look like in the pixi.toml

file we created for a linux-64 platform machine.

version: 6

environments:

default:

channels:

- url: https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/

packages:

linux-64:

...

- conda: https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/python-3.13.5-hec9711d_102_cp313.conda

- conda: https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/noarch/python_abi-3.13-8_cp313.conda

- conda: https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/readline-8.2-h8c095d6_2.conda

- conda: https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/tk-8.6.13-noxft_hd72426e_102.conda

- conda: https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/noarch/tzdata-2025b-h78e105d_0.conda

...

packages:

...

- conda: https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/python-3.13.5-hec9711d_102_cp313.conda

build_number: 102

sha256: c2cdcc98ea3cbf78240624e4077e164dc9d5588eefb044b4097c3df54d24d504

md5: 89e07d92cf50743886f41638d58c4328

depends:

- __glibc >=2.17,<3.0.a0

- bzip2 >=1.0.8,<2.0a0

- ld_impl_linux-64 >=2.36.1

- libexpat >=2.7.0,<3.0a0

- libffi >=3.4.6,<3.5.0a0

- libgcc >=13

- liblzma >=5.8.1,<6.0a0

- libmpdec >=4.0.0,<5.0a0

- libsqlite >=3.50.1,<4.0a0

- libuuid >=2.38.1,<3.0a0

- libzlib >=1.3.1,<2.0a0

- ncurses >=6.5,<7.0a0

- openssl >=3.5.0,<4.0a0

- python_abi 3.13.* *_cp313

- readline >=8.2,<9.0a0

- tk >=8.6.13,<8.7.0a0

- tzdata

license: Python-2.0

size: 33273132

timestamp: 1750064035176

python_site_packages_path: lib/python3.13/site-packages

...These groups provide a full description of every package described in the Pixi workspace and its dependencies and constraints on other packages. This means that for each package specified, that version, and only that version, will be downloaded and installed in the future.

We can even test that now by deleting the installed environment fully

with pixi clean

and then getting it back (bit for bit) in a few seconds with pixi install.

OUTPUT

removed /home/<username>/pixi-lesson/example/.pixi/envsOUTPUT

✔ The default environment has been installed.We can also see all the packages that were installed and are now

available for us to use with pixi list

Extending the manifest

Let’s extend this manifest to add the Python library

numpy and the Jupyter tools notebook and

jupyterlab as dependencies and add a task called

lab that will launch Jupyter Lab in the current working

directory.

Hint: Look at the Pixi manifest table structure to think how a

task might be added. It is fine to read the docs too!

Let’s start at the command line and add the additional dependencies

with pixi add

We can manually edit the pixi.toml with a text editor to

add a task named lab that when called executes

jupyter lab. This is sometimes the easiest thing to do, but

we can also use the pixi CLI.

OUTPUT

✔ Added task `lab`: jupyter lab, description = "Launch JupyterLab"The resulting pixi.toml manifest is

With our new dependencies added to the project manifest and our

lab task defined, let’s use all of them together by

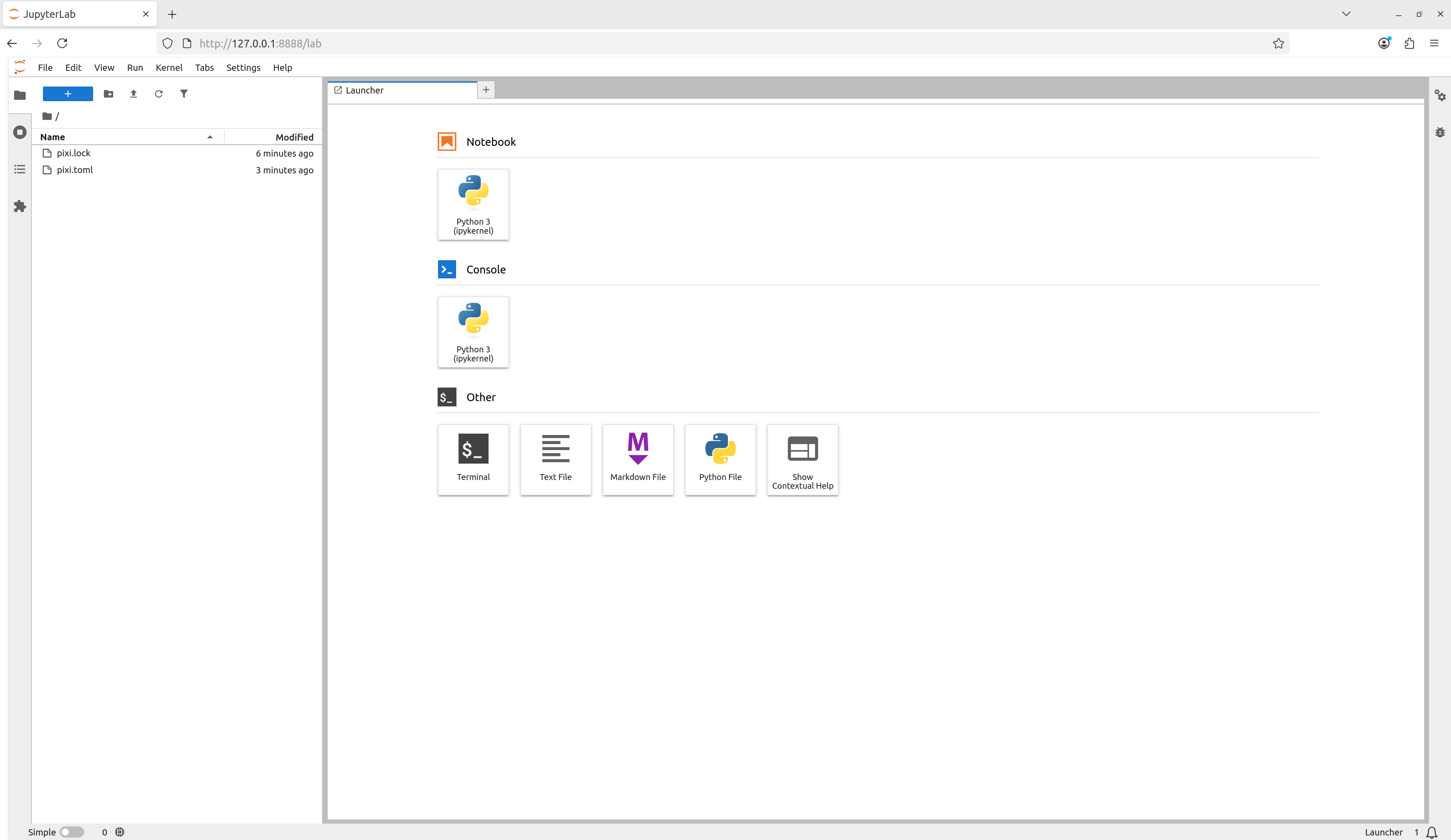

launching our task using pixi run

and we see that Jupyter Lab launches!

Adding the canonical Pixi start

task

For Pixi projects, it is canonical to have a start task

so that for any Pixi project a user can navigate to the top level

directory of a project run

and begin to explore the project. Add a task called

start that depends-on

the lab task.

Task overview

Here we used pixi run

to execute tasks in the workspace’s environments without ever explicitly

activating the environment. This is a different behavior compared to

tools like conda of Python virtual environments, where the assumption is

that you have activated an environment before using it. With Pixi we can

do the equivalent with pixi shell,

which starts a subshell in the current working directory with the Pixi

environment activated.

Notice how your shell prompt now has (example) (the

workspace name) preceding it, signaling to you that you’re in the

activated environment. You can now directly run commands that use the

environment.

OUTPUT

Python 3.13.5 | packaged by conda-forge | (main, Jun 16 2025, 08:27:50) [GCC 13.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>As we’re in a subshell, to exit the environment and move back to the

shell that launched the subshell, just exit the shell.

Multi platform projects

Extend your project to additionally support the

linux-64, osx-arm64, and win-64

platforms.

Using the pixi workspace

CLI API, one can add the platforms with

OUTPUT

✔ Added linux-64

✔ Added osx-arm64

✔ Added win-64This both adds the platforms to the workspace

platforms list and solves for the platforms and updates the

lock file!

One can also manually edit the pixi.toml with a text

editor to add the desired platforms to the platforms

list.

The resulting pixi.toml manifest is

TOML

[workspace]

channels = ["conda-forge"]

name = "example"

platforms = ["linux-64", "osx-arm64", "win-64"]

version = "0.1.0"

[tasks.lab]

description = "Launch JupyterLab"

cmd = "jupyter lab"

[tasks.start]

description = "Start exploring the Pixi project"

depends-on = ["lab"]

[dependencies]

python = ">=3.13.5,<3.14"

numpy = ">=2.3.2,<3"

notebook = ">=7.4.5,<8"

jupyterlab = ">=4.4.5,<5"Pixi features

“Features” in Pixi are TOML tables that define a part of an environment, but by itself is not useable. Features can be composed together to create an environment — think of how individual LEGO bricks (features) can be connected together to build a larger structure (an environment). Features can also be used across multiple environments, which allows for building complex environment structures without having to redefine sections.

Pseudo-example: The following Pixi manifest structure defines three

“features” (A, B, and C) and then

constructs four different environments (A,

two, three, alternative) by

composing the features together.

So far the Pixi project has only had one environment defined in it.

We can make the project

multi-environment by first defining a new “feature”

which provides all the fields necessary to define part of an

environment to extend the default environment. We can

create a new feature named dev and then create

an environment also named dev which uses the

dev feature to extend the default environment

TOML

[workspace]

channels = ["conda-forge"]

name = "example"

platforms = ["linux-64", "osx-arm64", "win-64"]

version = "0.1.0"

[tasks.lab]

description = "Launch JupyterLab"

cmd = "jupyter lab"

[tasks.start]

description = "Start exploring the Pixi project"

depends-on = ["lab"]

[dependencies]

python = ">=3.13.5,<3.14"

numpy = ">=2.3.0,<3"

notebook = ">=7.4.3,<8"

jupyterlab = ">=4.4.3,<5"

[feature.dev.dependencies]

[environments]

dev = ["dev"]We can now add pre-commit to the dev

feature’s dependencies and have it be accessible in the

dev environment.

OUTPUT

✔ Added pre-commit >=4.2.0,<5

Added these only for feature: devTOML

[workspace]

channels = ["conda-forge"]

name = "example"

platforms = ["linux-64", "osx-arm64", "win-64"]

version = "0.1.0"

[tasks.lab]

description = "Launch JupyterLab"

cmd = "jupyter lab"

[tasks.start]

description = "Start exploring the Pixi project"

depends-on = ["lab"]

[dependencies]

python = ">=3.13.5,<3.14"

numpy = ">=2.3.2,<3"

notebook = ">=7.4.5,<8"

jupyterlab = ">=4.4.5,<5"

[feature.dev.dependencies]

pre-commit = ">=4.3.0,<5"

[environments]

dev = ["dev"]This now allows us to specify the environment we want tasks to run in

with the --environment flag

Global Tools

With the pixi global

CLI API, users can manage globally installed tools in a way that

makes them available from any directory on their machine.

As an example, we can install the bat program — a

cat clone with syntax highlighting and Git integration — as

a global utility from conda-forge using pixi global.

OUTPUT

└── bat: 0.25.0 (installed)

└─ exposes: batPixi has now installed bat for us in a custom

environment under ~/.pixi/envs/bat/ and then exposed the

bat command globally by placing bat on our

shell’s PATH at ~/.pixi/bin/bat. This now

means that for any new terminal shell we open, bat will be

available to use.

Using pixi global has also created a

~/.pixi/manifests/pixi-global.toml file that tracks all of

the software that is globally installed by Pixi

TOML

version = 1

[envs.bat]

channels = ["conda-forge"]

dependencies = { bat = "*" }

exposed = { bat = "bat" }As new software is added to the system with pixi global

this global manifest is updated. If the global manifest is updated

manually, the next time pixi global update is run, the

environments defined in the global manifest will be installed on the

system. This means that by sharing a Pixi global manifest, a new machine

can be provisioned with an entire suite of command line tools in

seconds.

Version controlling our examples

As part of this lesson, we are building up a Git repository of the examples that we move through. On a new branch in your repository, add and commit the files from the this episode.

Then push your branch to your remote on GitHub

and make a pull request to merge your changes into your remote’s default branch.

We’ll follow this pattern for every episode: * Create a new feature branch * Add and commit work to a pull request as we go * Merge the pull request at the end

- Pixi uses a project based workflow and a declarative project manifest file to define project operations.

- Pixi automatically creates or updates a hash level lock file anytime the project manifest or dependencies are mutated.

- Pixi allows for multi-platform and multi-environment projects to be defined in a single project manifest and be fully described in a single lock file.

Content from Backwards compatibility with conda

Last updated on 2026-01-30 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- Can Pixi environments be backported to conda formats?

Objectives

- Learn how to export Pixi workspace environments as conda environment definition files

- Learn how to export Pixi workspace environments as conda explicit spec files

Backporting to conda environments

While Pixi is currently unique in its abilities, there may be

situations in which given technical debt, migration effort in large

collaborations, or collaborator preferences that switching all

infrastructure to use Pixi might not yet be feasible. It would still be

useful to take advantage of Pixi’s technology and features as an

individual but be able to export Pixi workspace environments and lock

files to the “legacy system” of conda. 1 Luckily, we can do

this with the pixi workspace export

commands.

Exporting workspace environments to conda environment definition files

If you want to export a Pixi workspace environment’s high level

dependencies to a conda environment definition file

(environment.yaml) you can use the pixi workspace export conda-environment

subcommand

BASH

pixi workspace export conda-environment --environment <environment> --platform <platform> environment.yamlwhere if no environment or platform options

are given the default environment and the system’s platform will be

used.

Export one of your Pixi workspace environments to a conda environment

Exporting workspace environments to conda explicit spec files

We’d like to ideally go further than the high level conda environment

definition file and aim for computational reproducibility with a conda

explicit spec file. Conda explicit spec files are a form of platform

specific lock files that consist of a text file with an

@EXPLICIT header followed by a list of conda package URLs,

optionally followed by their MD5 or SHA256 digest (aka, “hash”).

Example:

TXT

@EXPLICIT

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/noarch/python_abi-3.13-7_cp313.conda#e84b44e6300f1703cb25d29120c5b1d8Explicit spec files can be created from locked Pixi workspace

environments with the pixi workspace export conda-explicit-spec

subcommand

where if no environment or platform options

are given the default environment and the system’s platform will be

used. The explicit spec file will be automatically named with the form

<environment>_<platform>_conda_spec.txt. So if

you are on a linux-64 machine and didn’t specify an

environment name, your generated explicit spec file will be named

default_linux-64_conda_spec.txt.

Conda spec files only support conda packages and do not support Python packages or source packages.

Export one of your Pixi workspace environment lock files as a conda explicit spec file

Hint: Check the --help output.

OUTPUT

# Generated by `pixi workspace export`

# platform: linux-64

@EXPLICIT

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/libgomp-15.1.0-h767d61c_4.conda#3baf8976c96134738bba224e9ef6b1e5

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/_libgcc_mutex-0.1-conda_forge.tar.bz2#d7c89558ba9fa0495403155b64376d81

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/_openmp_mutex-4.5-2_gnu.tar.bz2#73aaf86a425cc6e73fcf236a5a46396d

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/libgcc-15.1.0-h767d61c_4.conda#f406dcbb2e7bef90d793e50e79a2882b

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/xorg-libxdmcp-1.1.5-hb9d3cd8_0.conda#8035c64cb77ed555e3f150b7b3972480

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/xorg-libxau-1.0.12-hb9d3cd8_0.conda#f6ebe2cb3f82ba6c057dde5d9debe4f7

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/pthread-stubs-0.4-hb9d3cd8_1002.conda#b3c17d95b5a10c6e64a21fa17573e70e

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/libxcb-1.17.0-h8a09558_0.conda#92ed62436b625154323d40d5f2f11dd7

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/xorg-libx11-1.8.12-h4f16b4b_0.conda#db038ce880f100acc74dba10302b5630

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/xorg-libice-1.1.2-hb9d3cd8_0.conda#fb901ff28063514abb6046c9ec2c4a45

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/libgcc-ng-15.1.0-h69a702a_4.conda#28771437ffcd9f3417c66012dc49a3be

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/libuuid-2.38.1-h0b41bf4_0.conda#40b61aab5c7ba9ff276c41cfffe6b80b

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/xorg-libsm-1.2.6-he73a12e_0.conda#1c74ff8c35dcadf952a16f752ca5aa49

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/xorg-libxt-1.3.1-hb9d3cd8_0.conda#279b0de5f6ba95457190a1c459a64e31

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/noarch/tzdata-2025b-h78e105d_0.conda#4222072737ccff51314b5ece9c7d6f5a

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/libzlib-1.3.1-hb9d3cd8_2.conda#edb0dca6bc32e4f4789199455a1dbeb8

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/linux-64/tk-8.6.13-noxft_hd72426e_102.conda#a0116df4f4ed05c303811a837d5b39d8OUTPUT

# Generated by `pixi workspace export`

# platform: osx-arm64

@EXPLICIT

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/noarch/tzdata-2025b-h78e105d_0.conda#4222072737ccff51314b5ece9c7d6f5a

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/libzlib-1.3.1-h8359307_2.conda#369964e85dc26bfe78f41399b366c435

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/tk-8.6.13-h892fb3f_2.conda#7362396c170252e7b7b0c8fb37fe9c78

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/tktable-2.10-h3c7de25_7.conda#7c2e2e25a80f1538b0dcee34026bec42

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/ncurses-6.5-h5e97a16_3.conda#068d497125e4bf8a66bf707254fff5ae

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/readline-8.2-h1d1bf99_2.conda#63ef3f6e6d6d5c589e64f11263dc5676

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/bzip2-1.0.8-h99b78c6_7.conda#fc6948412dbbbe9a4c9ddbbcfe0a79ab

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/pcre2-10.45-ha881caa_0.conda#a52385b93558d8e6bbaeec5d61a21cd7

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/libpng-1.6.50-h280e0eb_1.conda#4d0f5ce02033286551a32208a5519884

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/libiconv-1.18-hfe07756_1.conda#450e6bdc0c7d986acf7b8443dce87111

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/libintl-0.25.1-h493aca8_0.conda#5103f6a6b210a3912faf8d7db516918c

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/libffi-3.4.6-h1da3d7d_1.conda#c215a60c2935b517dcda8cad4705734d

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/libglib-2.84.3-h587fa63_0.conda#bb98995c244b6038892fd59a694a93ed

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/libfreetype6-2.13.3-h1d14073_1.conda#b163d446c55872ef60530231879908b9

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/libfreetype-2.13.3-hce30654_1.conda#d06282e08e55b752627a707d58779b8f

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/libexpat-2.7.1-hec049ff_0.conda#b1ca5f21335782f71a8bd69bdc093f67

https://conda.anaconda.org/conda-forge/osx-arm64/libcxx-20.1.8-hf598326_1.conda#a69ef3239d3268ef8602c7a7823fd982While conda spec files meet our criteria for computational reproducibility, they are essentially package list snapshots and lack the metadata to provide robust dependency graph inspection and targeted updates. They can be a useful tool, but are not robust lock file formats like those from Pixi and conda-lock.

Creating conda environments from the exports

To create a conda environment from the exported

environment.yaml conda environment definition file, you use

the normal conda environment creation command

but to create a conda environment from the exported conda explicit spec file, use the command

or to install the packages given in the explicit spec file into an existing conda environment, use

So by using Pixi, you can fully export your workspace environments to conda environments and then use them, even to get the exact hash level locked environment from your Pixi workspace installed on another machine!

Conda does not check that the platform is correct for the machine or the dependencies given when installing from an explicit spec file. Only use spec files when you are certain that you have the same platform machine as the machine that created the spec file.

- If you need to use conda, you can export Pixi workspace environment to formats conda can use.

- Exporting conda explicit spec files from Pixi locked environments provides the ability to create the same hash level locked environment with conda that Pixi solved.

Conda is still a very well supported tool and the dominant conda package environment manager by numbers of users.↩︎