Data Structures & Algorithms

Last updated on 2026-02-25 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What’s the most efficient way to construct a list?

- When should tuples be used?

- When are sets appropriate?

- What is the best way to search a list?

Objectives

- Able to summarise how lists and tuples work behind the scenes.

- Able to identify appropriate use-cases for tuples.

- Able to utilise dictionaries and sets effectively

- Able to use

bisect_left()to perform a binary search of a list or array

This episode is challenging!

Within this episode you will be introduced to how certain data-structures and algorithms work.

This is used to explain why one approach is likely to execute faster than another.

It matters that you are able to recognise the faster/slower approaches, not that you can describe or reimplement these data-structures and algorithms yourself.

Lists

Lists are a fundamental data structure within Python.

It is implemented as a form of dynamic array found within many

programming languages by different names (C++: std::vector,

Java: ArrayList, R: vector, Julia:

Vector).

They allow direct and sequential element access, with the convenience to append items.

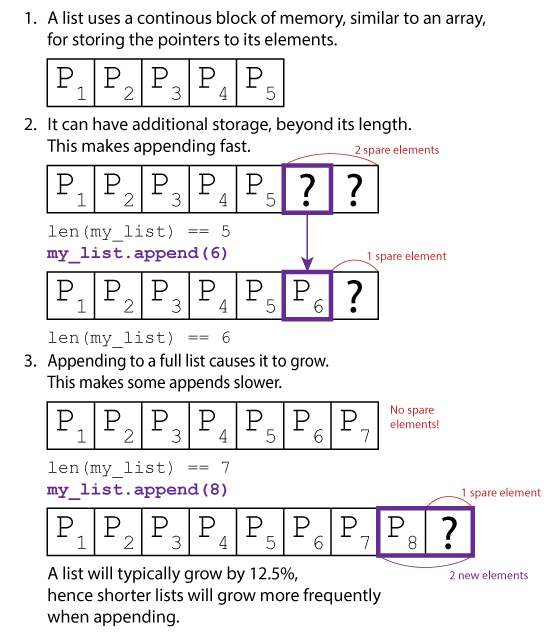

This is achieved by internally storing items in a static array. This array however can be longer than the list, so the current length of the list is stored alongside the array. When an item is appended, the list checks whether it has enough spare space to add the item to the end. If it doesn’t, it will re-allocate a larger array, copy across the elements, and deallocate the old array. The item to be appended is then copied to the end and the counter which tracks the list’s length is incremented.

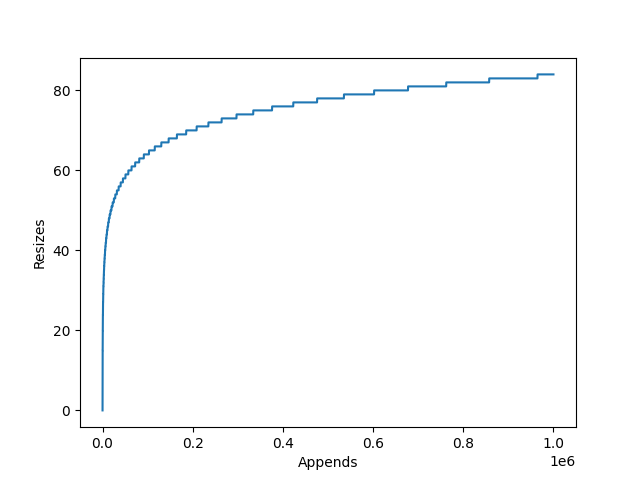

The amount the internal array grows by is dependent on the particular

list implementation’s growth factor. CPython for example uses newsize + (newsize >> 3) + 6,

which works out to an over allocation of roughly ~12.5%.

This has two implications:

- If you are growing a list with

append(), there will be large amounts of redundant allocations and copies as the list grows. - The resized list may use up to 12.5% excess memory.

List Comprehension

If creating a list via append() is undesirable, the

natural alternative is to use list-comprehension.

List comprehension can be twice as fast at building lists than using

append(). This is primarily because list-comprehension

allows Python to offload much of the computation into faster C code.

General Python loops in contrast can be used for much more, so they

remain in Python bytecode during computation which has additional

overheads.

This can be demonstrated with the below benchmark:

PYTHON

from timeit import timeit

def list_append():

li = []

for i in range(100_000):

li.append(i)

def list_preallocate():

li = [0]*100_000

for i in range(100_000):

li[i] = i

def list_comprehension():

li = [i for i in range(100_000)]

repeats = 1000

print(f"Append: {timeit(list_append, number=repeats):.2f} s")

print(f"Preallocate: {timeit(list_preallocate, number=repeats):.2f} s")

print(f"Comprehension: {timeit(list_comprehension, number=repeats):.2f} s")timeit is used to run each function 1000 times,

providing the below averages:

OUTPUT

Append: 3.50 s

Preallocate: 2.48 s

Comprehension: 1.69 sResults will vary between Python versions, hardware and list lengths. But in this example list comprehension was 2x faster, with pre-allocate fairing in the middle. Although this is milliseconds, this can soon add up if you are regularly creating lists.

Tuples

In contrast to lists, Python’s tuples are immutable static arrays (similar to strings): Their elements cannot be modified and they cannot be resized.

Their potential use-cases are greatly reduced due to these two limitations, they are only suitable for groups of immutable properties.

Tuples can still be joined with the + operator, similar

to appending lists, however the result is always a newly allocated tuple

(without a list’s over-allocation).

Python caches a large number of short (1-20 element) tuples. This greatly reduces the cost of creating and destroying them during execution at the cost of a slight memory overhead.

This can be easily demonstrated with Python’s timeit

module in your console.

SH

>python -m timeit "li = [0,1,2,3,4,5]"

10000000 loops, best of 5: 26.4 nsec per loop

>python -m timeit "tu = (0,1,2,3,4,5)"

50000000 loops, best of 5: 7.99 nsec per loopIt takes 3x as long to allocate a short list than a tuple of equal length. This gap only grows with the length, as the tuple cost remains roughly static whereas the cost of allocating the list grows slightly.

Dictionaries

Dictionaries are another fundamental Python data-structure. They provide a key-value store, whereby unique keys with no intrinsic order map to attached values.

“no intrinsic order”

Since Python 3.6, the items within a dictionary will iterate in the order that they were inserted. This does not apply to sets.

OrderedDict still exists, and may be preferable if the

order of items is important when performing whole-dictionary

equality.

Hashing Data Structures

Python’s dictionaries are implemented as hashing data structures, we can understand these at a high-level with an analogy:

A Python list is like having a single long bookshelf. When you buy a new book (append a new element to the list), you place it at the far end of the shelf, right after all the previous books.

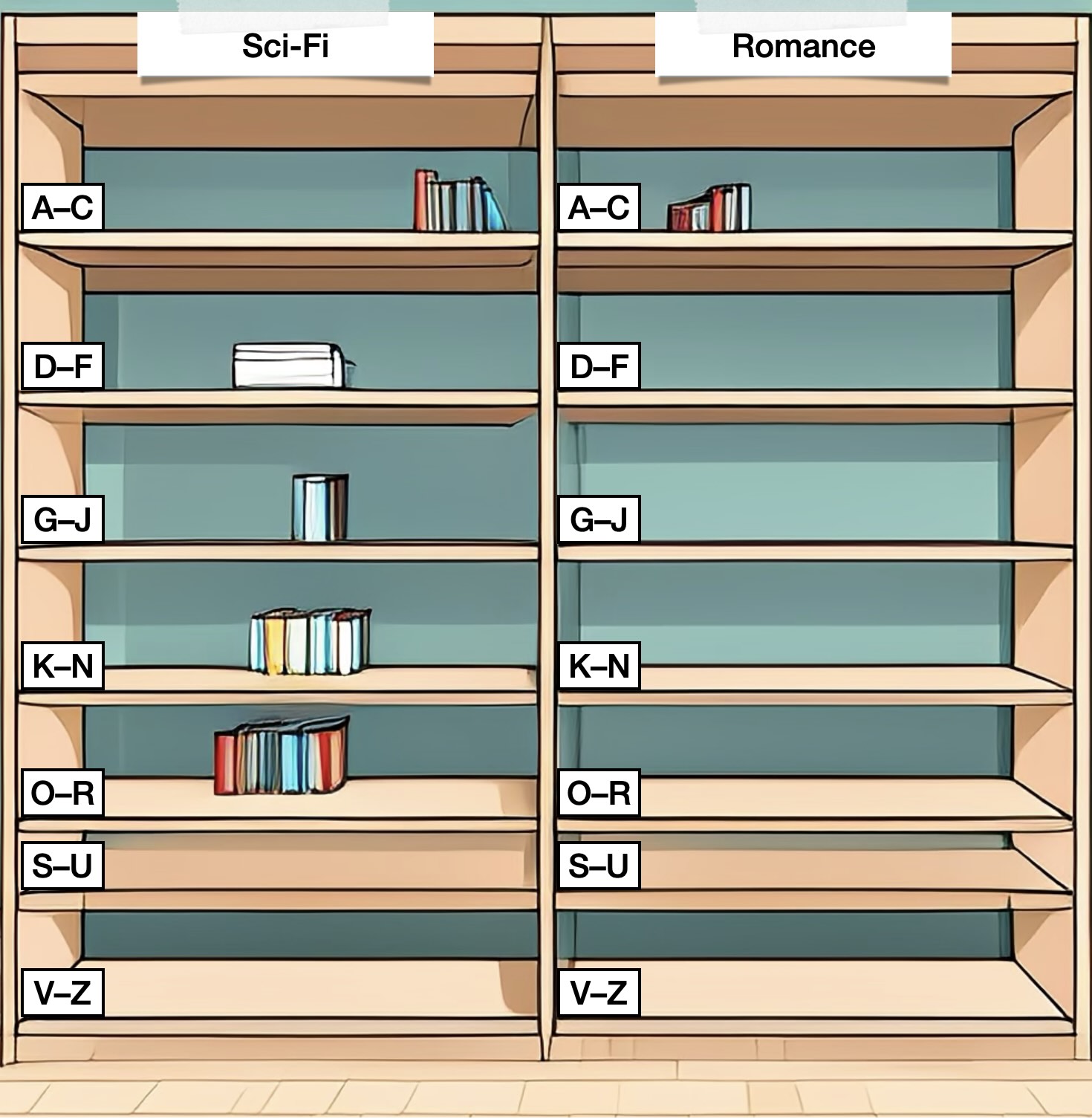

A Python dictionary is more like a bookcase with several shelves, labelled by genre (sci-fi, romance, children’s books, non-fiction, …) and author surname. When you buy a new book by Jules Verne, you might place it on the shelf labelled "Sci-Fi, V–Z". And if you keep adding more books, at some point you’ll move to a larger bookcase with more shelves (and thus more fine-grained sorting), to make sure you don’t have too many books on a single shelf.

Now, let’s say a friend wanted to borrow the book "‘—All You Zombies—’" by Robert Heinlein. If I had my books arranged on a single bookshelf (in a list), I would have to look through every book I own in order to find it. However, if I had a bookcase with several shelves (a hashing data structure), I know immediately that I need to check the shelf "Sci-Fi, G—J", so I’d be able to find it much more quickly!

When a value is inserted into a dictionary, its key is hashed to decide on which “shelf” it should be stored. Most items will have a unique shelf, allowing them to be accessed directly. This is typically much faster for locating a specific item than searching a list.

Keys

A dictionary’s keys will typically be a core Python type such as a

number or string. However, multiple of these can be combined as a tuple

to form a compound key, or a custom class can be used if the methods

__hash__() and __eq__() have been

implemented.

You can implement __hash__() by utilising the ability

for Python to hash tuples, avoiding the need to implement a bespoke hash

function.

PYTHON

class MyKey:

def __init__(self, _a, _b, _c):

self.a = _a

self.b = _b

self.c = _c

def __eq__(self, other):

return (isinstance(other, type(self))

and (self.a, self.b, self.c) == (other.a, other.b, other.c))

def __hash__(self):

return hash((self.a, self.b, self.c))

dict = {}

dict[MyKey("one", 2, 3.0)] = 12The only limitation is that where two objects are equal they must

have the same hash, hence all member variables which contribute to

__eq__() should also contribute to __hash__()

and vice versa (it’s fine to have irrelevant or redundant internal

members contribute to neither).

Sets

Sets are dictionaries without the values (both are declared using

{}), a collection of unique keys equivalent to the

mathematical set. Modern CPython now uses a set implementation

distinct from that of its dictionary, however they still behave much the

same in terms of performance characteristics.

Sets are used for eliminating duplicates and checking for membership, and will normally outperform lists especially when the list cannot be maintained sorted.

Exercise: Unique Collection

There are four implementations in the below example code, each builds a collection of unique elements from 25,000 where 50% can be expected to be duplicates.

Estimate how the performance of each approach is likely to stack up.

If you reduce the value of repeats it will run faster,

how does changing the number of items (N) or the ratio of

duplicates int(N/2) affect performance?

PYTHON

import random

from timeit import timeit

N = 25_000 # Number of elements in the list

data = [random.randint(0, int(N/2)) for i in range(N)]

def uniqueSet():

set_out = set(data)

def uniqueSetAdd():

set_out = set()

for i in data:

set_out.add(i)

def uniqueList():

ls_out = []

for i in data:

if not i in ls_out:

ls_out.append(i)

def uniqueListSort():

ls_in = sorted(data)

ls_out = [ls_in[0]]

for i in ls_in:

if ls_out[-1] != i:

ls_out.append(i)

repeats = 100

print(f"uniqueSet: {timeit(uniqueSet, number=repeats):.3f} s")

print(f"uniqueSetAdd: {timeit(uniqueSetAdd, number=repeats):.3f} s")

print(f"uniqueList: {timeit(uniqueList, number=repeats):.3f} s")

print(f"uniqueListSort: {timeit(uniqueListSort, number=repeats):.3f} s")-

uniqueSet()passes the input list to the constructorset(). -

uniqueSetAdd()creates an empty set, and then iterates the input list adding each item individually. -

uniqueList()this naive approach, checks whether each item in the input list exists in the output list before appending. -

uniqueListSort()sorts the input list, allowing only the last item of the output list to be checked before appending.

There is not a version using list comprehension, as it is not possible to refer to the list being constructed during list comprehension.

Constructing a set by passing in a single list is the clear winner.

Constructing a set with a loop and add() (equivalent to

a list’s append()) comes in second. This is slower due to

the pythonic loop, whereas adding a full list at once moves this to

CPython’s back-end.

The naive list approach is 2200x times slower than the fastest approach, because of how many times the list is searched. This gap will only grow as the number of items increases.

Sorting the input list reduces the cost of searching the output list significantly, however it is still 8x slower than the fastest approach. In part because around half of its runtime is now spent sorting the list.

OUTPUT

uniqueSet: 0.030 s

uniqueSetAdd: 0.081 s

uniqueList: 66.071 s

uniqueListSort: 0.267 sSearching

Independent of the performance to construct a unique set (as covered in the previous section), it’s worth identifying the performance to search the data-structure to retrieve an item or check whether it exists.

The performance of a hashing data structure is subject to the load factor and number of collisions. An item that hashes with no collision can be accessed almost directly, whereas one with collisions will probe until it finds the correct item or an empty slot. In the worst possible case, whereby all insert items have collided this would mean checking every single item. In practice, hashing data-structures are designed to minimise the chances of this happening and most items should be found or identified as missing on the first attempt (without probing beyond the original hash).

In contrast, if searching a list or array, the default approach is to start at the first item and check all subsequent items until the correct item has been found. If the correct item is not present, this will require the entire list to be checked. Therefore the worst-case is similar to that of the hashing data-structure, however it is guaranteed in cases where the item is missing. Similarly, on-average we would expect an item to be found halfway through the list, meaning that an average search will require checking half of the items.

If however the list or array is sorted, a binary search can be used.

A binary search divides the list in half and checks which half the

target item would be found in, this continues recursively until the

search is exhausted whereby the item should be found or dismissed. This

is significantly faster than performing a linear search of the list,

checking a total of log N items every time.

The below code demonstrates these approaches and their performance.

PYTHON

import random

from timeit import timeit

from bisect import bisect_left

N = 25_000 # Number of elements in list

M = 2 # N*M == Range over which the elements span

st = set([random.randint(0, N*M) for i in range(N)])

ls = list(st)

ls.sort() # Sort required for binary search

def search_set():

j = 0

for i in range(0, N*M, M):

if i in st:

j += 1

def linear_search_list():

j = 0

for i in range(0, N*M, M):

if i in ls:

j += 1

def binary_search_list():

j = 0

for i in range(0, N*M, M):

k = bisect_left(ls, i)

if k != len(ls) and ls[k] == i:

j += 1

repeats = 10

print(f"search_set: {timeit(search_set, number=repeats):.4f} s")

print(f"linear_search_list: {timeit(linear_search_list, number=repeats):.2f} s")

print(f"binary_search_list: {timeit(binary_search_list, number=repeats):.4f} s")Searching the set is fastest, performing the task in 5.7 ms. This is followed by the binary search of the (sorted) list which is 6x slower, although the list has been filtered for duplicates. A list still containing duplicates would be longer, leading to a more expensive search. The linear search of the list is about 2700x slower than the fastest, it really shouldn’t be used!

OUTPUT

search_set: 0.0057 s

linear_search_list: 15.32 s

binary_search_list: 0.0343 sThese results are subject to change based on the number of items and the proportion of searched items that exist within the list. However, the pattern is likely to remain the same. Linear searches should be avoided!

- List comprehension should be preferred when constructing lists.

- Where appropriate, tuples should be preferred over Python lists.

- Dictionaries and sets are appropriate for storing a collection of unique data with no intrinsic order for random access.

- When used appropriately, dictionaries and sets are significantly faster than lists.

- If searching a list or array is required, it should be sorted and

searched using

bisect_left()(binary search).