Code testing and Review

Last updated on 2023-02-17 | Edit this page

Code Testing

Overview

Questions

- What are the main objectives and best practices for testing and reviewing code?

- What can continous integration help?

- How can group leaders facilitate a collaborative environment for code review?

Objectives

- Explain different processes and best practices for code review.

- Discuss tips, tricks and benefits of code review.

- Share some ways to involve all group members in code review.

You should not skip writing tests because you are short on time, you should write tests because you are short on time.

The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY

4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY

4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

It is very, very easy to make mistakes when coding. A single wrong use of a character can cause a program’s output to be entirely wrong. Missing one data point, writing plus instead of minus symbol or using feet instead of meters might be a genuine human mistake, but in research, the results can be catastrophic. Careers can be damaged/ended, vast sums of research funds can be wasted, and valuable time may be lost exploring incorrect avenues. This is why code testing is vital.

Testing is a learned skill that needs to become a part of working on/improving a project. After changing their code, researchers should always check that their changes or fixes have not broken anything. There are several different kinds of testing and each has best practices specific to them.

A few important testing types

- Smoke testing: Very brief initial checks that ensure the basic requirements required to run the project hold. If these fail there is no point in proceeding to additional levels of testing until they are fixed.

- Unit testing: A level of the software testing process where individual units of a software are tested. The purpose is to validate that each unit of the software performs as designed.

- Integration testing: A level of software testing where individual units are combined and tested as a group. The purpose of this level of testing is to expose faults in the interaction between integrated units.

- System testing: A level of the software testing process where a complete, integrated system is tested. The purpose of this test is to evaluate whether the system as a whole gives the correct outputs for given inputs.

No matter the type of testing you use, general guidance is to start by writing any test and make a habit of running tests often.

- Make improvements where you can, and do your best to include tests with new code you write even if it’s not feasible to write tests for all the code that’s already written.

- Make the cases you test as realistic as possible. If for example, you have dummy data to run tests on you should make sure that data is as similar as possible to the actual data. If your actual data is messy with a lot of null values, so should your test dataset be.

There are tools available to make writing and running tests easier, these are known as testing frameworks. Find one you like, learn about the features it offers, and make use of them.

Writing tests typically encourage researchers to write cleaner, more modular code as such code is far easier to write tests for, leading to an improvement in code quality. As well as advantaging individual researchers testing also benefits research as a whole. It makes research more reproducible by answering the question “how do we even know this code works”. To gain an in-depth understanding of different kinds of tests, please see Code Testing chapter in The Turing Way.

Code Review

Testimonial

The most difficult part of writing code is always to make it understandable to other people, including yourself a few months down the track. There’s certainly no shame in finding out that your code wasn’t as easy to understand or use as you’d hoped, so don’t take it personally when it happens (which it always does, at least in my experience), but treat it as an opportunity to improve.

Fernando Perez, Code reviews: the lab meeting for code

A simple objective of the review process is to catch bugs and elementary errors that might have been missed during the development phase. Code review can also help improve the overall quality while ensuring that code is readable and easy to understand. As a group leader, you can also make sure code is functional and literate as early as possible, and encourage your students to avoid messy “good enough” code that causes chaos later.

Code review is often done in pairs, with each reviewer also having some of their code reviewed by their partner. Doing this can help programmers to see and discuss issues and alternative approaches to tasks, and to learn new tips and tricks.

The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

There are different methods for code review.

Synchronous - Pair Programming

Helping the student go through their scripts, catch errors and debug side by side

- The PI sits down with her PhD student who has been writing a function for cleaning bioinformatics data.

- The PI knows Python well and takes the opportunity to discuss code while helping their student organise the code better.

- The student shows the PI some odd errors and so they run some tests with expected outcomes to find what the problem is and solve it.

- The PhD student learns and applies to test practices to help make code robust.

The problem with synchronous coding sessions is making time for it and whether or not the supervisor has experience with the specific language.

Synchronous - Group Code Tour or Informal Walkthroughs

Narrating code and software steps

The researcher may present their pipeline to describe the logical steps using documentation, pseudocode, or describing how to run the code.

- A postdoc has been working on some analysis that provides statistics results that he hopes to publish soon. During a lab meeting, the postdoc presents the steps of the analysis code as logical steps.

- The lines of code are shown for those in the meeting that know R, but the postdoc explains the steps verbally as well for those who don’t understand R.

- The group discuss and provides comments on the choices and order of the analysis pipeline, a PhD student notices a jump in logic that wasn’t picked up previously, and an advanced R user in the lab makes suggestions about making some parts run faster.

These sessions do not rely on everyone knowing the language, and it is the responsibility of the coder to present their work clearly and logically for everyone to follow. Group discussions can be very informative for everyone involved and put the analysis under scrutiny.

Suggestions for the meeting leader

- Keep it a safe environment, i.e. make sure chastising is relatively gentle even when deserved (but do point out when code doesn’t meet the required standard – frame it as a learning experience though).

- Make sure there’s a core of vocal participants so it isn’t always you.

- Make it clear when you’re presenting yourself that your code isn’t perfect, point out some of those imperfections yourself if the audience is slow to do so, and do present yourself.

- Patiently explain when things are not wrong but just stylistic differences (but make it clear that some styles are bad, often helpful e.g. asking people to guess what a function returns from its name).

Shared by Rob Knight with Fernando Perez in the post Code reviews: the lab meeting for code

Asynchronous - I’ll get back to you on that

Making sure everyone is free at the same time for a lab meeting can be challenging. Hence, asynchronous code review practices are more suitable for busy supervisors or collaborators in different time zones.

The asynchronous review process allows others to run the code themselves using a reproducible environment, or simply reads through the scripts and share their feedback asynchronously.

Consider a scenario:

A postdoc has created a model in Python and creates a Binder with all the dependencies necessary. She sends the file to her supervisor who can run the code within her browser, no installation is required. The supervisor can then run the code herself to review it and check the individual parts over the next week. The supervisor adds a commented version of the script to the postdoc’s repo with a merge request.

Reviewing code in small chunks incrementally as the project is developing can help make the code review process a lot more efficient. Asynchronous feedback removes the time pressure but can be easily forgotten!

Testimonial

Reviewing more than 400 lines of code (LoC) can have an adverse impact on your ability to find bugs, and in fact, most are found in the first 200 lines. - Recommendation from Code Review at Cisco Systems

5 code review best practices. Work Life by Atlassian, Usman Ghani

Multiple people can also review the code asynchronously.

Callout

Turing Way: Recommendations for Code Reviewing

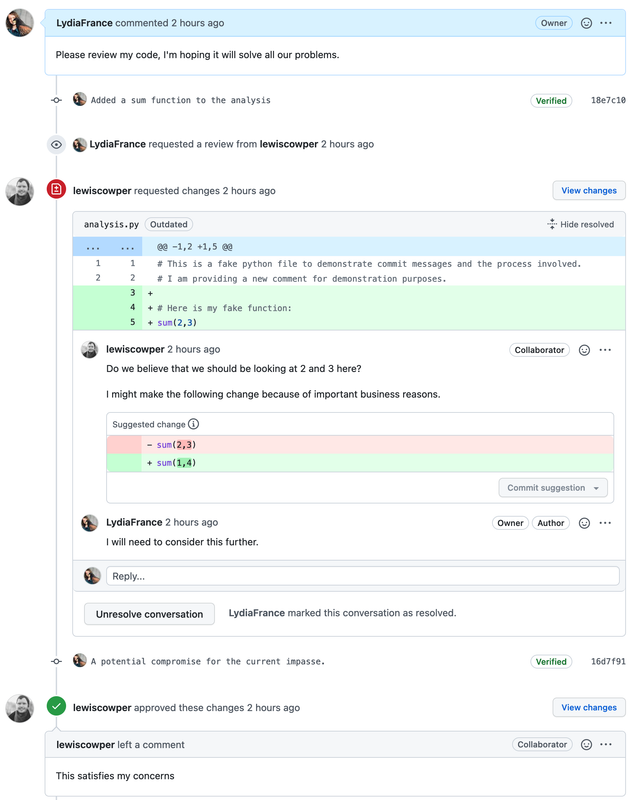

Unlike traditional, “academic-style” peer review, most code review systems have several advantages: they’re rarely anonymous, they’re public-facing, and without the broker of an editor, contact between reviewer and reviewee can be direct and rapid. This means code review is typically a fast, flexible, and interactive process.

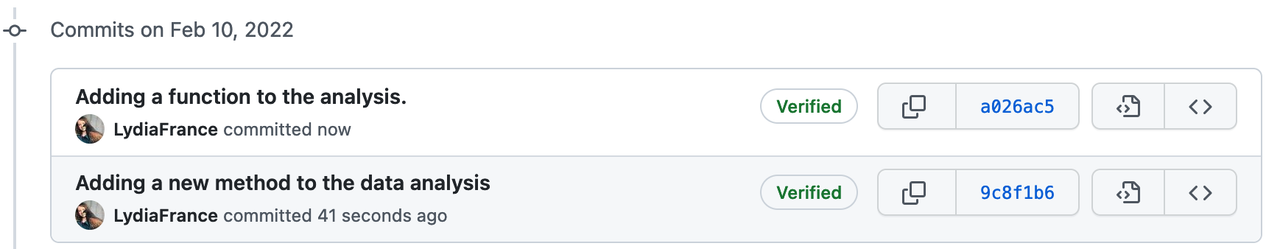

Commit changes: uploading snapshots when the code changes. The history of all changes are therefore saved and can be reverted.

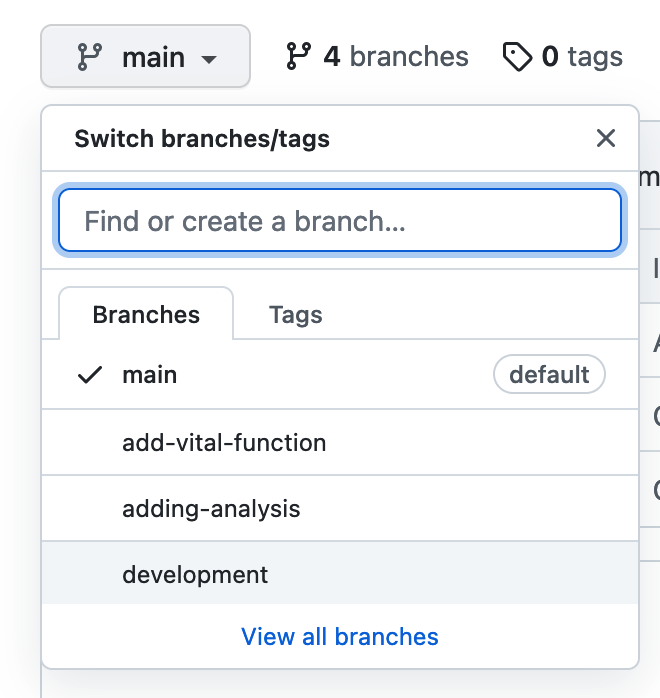

Branching: keep a version of the code separate while making experimental changes or keeping track of collaborative work. Can try out new functionality or edit in parallel without impacting the code base.

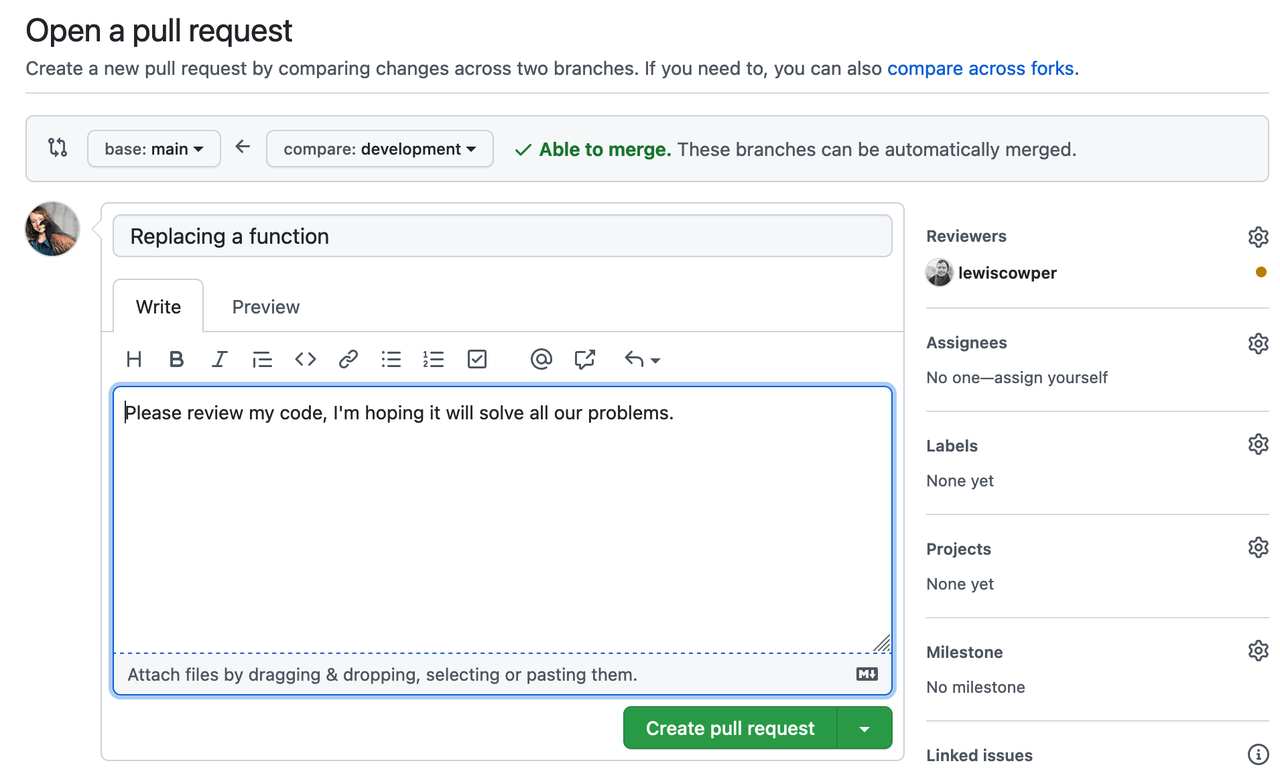

Pull Request: Bring the changes made on a branch over to the main code base. Can be used to request a code review (see Reviewers on the right panel)

Review: A pull request can be reviewed and commented on.

Author: Lydia France (Junior Data Scientist, The Alan Turing Institute, UK)

Reviewing is not about creating more work, nor the PI rewriting everything

Instead, it is just another part of peer review and accountability within the scientific process. It is also an opportunity for everyone to learn better practices from each other, and solve issues that have plagued one person for weeks!

Callout

Scientists are very aware that their understanding of code dissipates over time and that this is a large hidden cost. Equally, they suspect that they spend a lot of time reinventing wheels. They may not know how code review will help with that, but they hope that it will.

One of the mentors expected scientists to overhaul complete code bases. The advice from one mentor was cogent: if you check the docstring and write a test every time you touch a method, the code improvements will accumulate over time with minimal effort.

Someone who isn’t intimately involved with your project should understand from the module documentation and the comments what you are trying to do, what approach you’re taking, and why they should expect it to work.

Take some time to prepare a presentation about your code that will answer the above questions even for someone who hasn’t read the code. You’re more likely to get useful feedback, rather than nitpicking about syntax, if the audience can see the big picture.

Keep it a safe environment, i.e. make sure chastising is relatively gentle even when deserved (but do point out when code doesn’t meet the required standard – frame it as a learning experience though).

Marian Petre and Greg Wilson. “Code review for and by scientists: preliminary findings.” (2014).

For further considerations in code review, please read Code Reviewing Process chapter in The Turing Way.

What to look for during Code Review

Reviewing code makes a big difference. Knowledge of the language is not always necessary!

These are very common, everyone does this.

Bugs/Potential bugs

- Repetitive code

- Code saying one thing, documentation saying another

- Off-by-one errors

- Making sure each function does one thing only

- Lack of tests and sanity checks for what different parts are doing

- Magic numbers (a number hardcoded in the script)

Unclear, messy code

- Bad variable/method names

- Inconsistent indentation

- The order of the different steps

- Too much on one line

- Lack of comments and signposting

Fragile and non-reusable code

- Tailor-made and manual steps

- Only works with the given data

Modified from What to look for when code reviewing

Benefits of Code Review

Testimonial

In a group of 11 programs developed by the same group of people, the first 5 were developed without reviews. The remaining 6 were developed with reviews. After all the programs were released to production, the first 5 had an average of 4.5 errors per 100 lines of code. The 6 that had been inspected had an average of only 0.82 errors per 100. Reviews cut the errors by over 80 percent.

Code Complete by Steve McConnell

The main benefit is finding problems, and finding them early enough that there aren’t frustrating consequences. The penalty for finding a bug once all the figures have been produced and conclusions drawn, or, worst-case scenario, after a publication, is much higher than the penalty for taking the time to review.

For a group leader, the benefits include:

- Better understanding of the projects

- More maintainable and better-documented code that is easy to understand and modify

- Better insight into any problems with data

- Earlier visibility of quality issues

- Group reviews reduce the work burden

- More robust analysis pipelines that can be reused and modified

- High-quality code that can be released

Important things to bear in mind:

Code reviews should not be used to evaluate individuals and their skill levels. An open and safe environment where revealing mistakes and errors should not come with penalties or shame. Code reviews should also be done early and often, to normalise this practice in the research team.

In their book Peer Reviews in Software: A Practical Guide, Karl E. Wiegers says:

The temptation to perfect the product before you allow another pair of eyes to see it. This is an ego-protecting strategy: you won’t feel embarrassed about your mistakes if no one else sees them. …review [is not] a seal of approval but rather in-process quality-improvement activity. Such reluctance has several unfortunate consequences. If your work isn’t reviewed until you think it’s complete, you are psychologically resistant to suggestions for changes.

If the program runs, how bad can it be? You are likely to rationalise away possible bugs because you believe you’ve finished and you’re eager to move on to the next task. Relying on your own desk checking and unit testing ignores the greater efficiency of a peer review for finding many defects*

Group Code Writing

As well as reviewing specific scripts and analyses written by a single individual, can be very beneficial to solving programming problems as a team. Setting aside an afternoon to work as a group will help teach less experienced members of the group and more efficiently solve very difficult problems.

Groups of people working on a specific problem are often known as “Hackathons” in programming. These can last multiple days (hopefully with downtime!). With very large groups, people can work in pairs or small groups with delegated parts of the problem to solve and regularly meet back together to discuss and evaluate. If there is a complex solution in computational methods that most people in the group need, it makes sense to find it together.

Similarly, documentation sprints are useful to dedicate time to regularly bring a codebase to a good minimum standard. Splitting the task across the team as an event, creating documentation and working examples for code repos and releasing it can help others use your computational methods and tools to increase the impact of your work. Having regularly updated documentation also reduces onboarding time for new members picking up the shared methods in the lab.

Group work shares the burden and allows knowledge exchange and support within the team.

Continuous integration

Continuous Integration (CI) is the practice of integrating changes to a project made by individuals into a main, shared version frequently (usually multiple times per day). CI is also typically used to identify any conflicts and bugs that are introduced by changes, so they are found and fixed early, minimising the effort required to do so. Running tests regularly also saves humans from needing to do it manually. By making users aware of bugs as early as possible researchers (if the project is a research project) do not waste a lot of time doing work that may need to be thrown away, which may be the case if tests are run infrequently and results are produced using faulty code. There are many CI service providers, such as GitHub Actions that come with their own advantages and disadvantages.

The Turing Way

project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI:

10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

The Turing Way

project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI:

10.5281/zenodo.3332807.

To learn more about different CI tools and how to use them, please read the Continuous Integration chapter in The Turing Way.

References

- The Turing Way Community. (2021). The Turing Way: A handbook for reproducible, ethical and collaborative research (1.0.1). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5671094. Code Reviewing Process Chapter.

- Fernando Perez, Code reviews: the lab meeting for code

Keypoints

- There are many benefits of code review and this should be implemented and practised in research team culture as early and as frequently as possible.

- Synchronous code review creates opportunities for researchers to get feedback and learn from others in real-time.

- Asynchronous code review is a good practice when working with busy researchers or collaborators in different time zones.