Graphical Elements of a Chart

Last updated on 2023-12-18 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- When creating a chart, what components do I have to work with?

- Which chart components are easier for people to perceive accurately?

- How can chart components support a chart’s message?

Objectives

- List the graphical elements and their visual properties that are available for chart design

- Choose chart components that are easier for people to perceive accurately

- Practice choosing better charts for some common chart use cases

Graphical elements and visual properties

When we create a chart, we can choose many different ways to represent the message we wish to convey. But in two or three dimensions, there are only a few graphical elements we have to work with1:

- Point

- Line

- Area

- Volume

The data and data relationships we are representing in a chart have different quantities and categories. We can communicate this information through a graphical element’s visual properties2:

- Position

- Alignment on one or more scales

- Length

- Direction

- Angle

- Size (amount of Area or Volume)

- Curvature

- Shading

- Color

Challenge: Visual properties

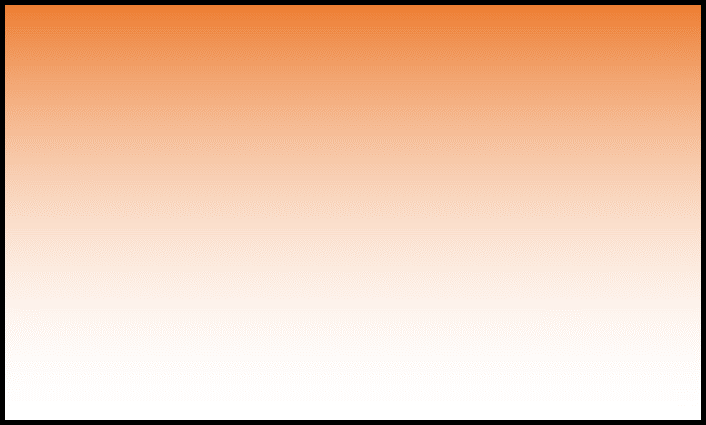

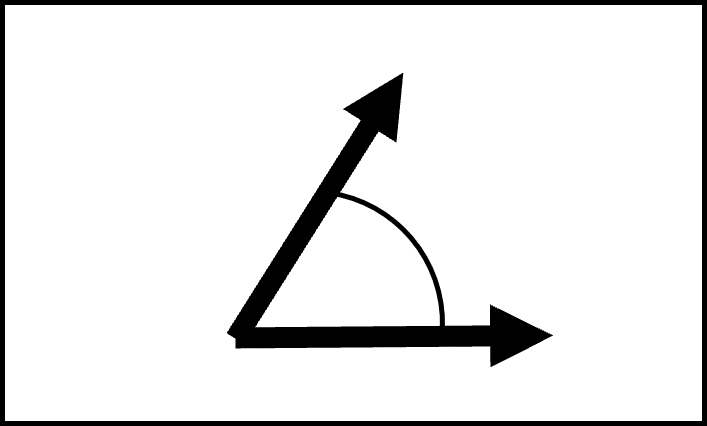

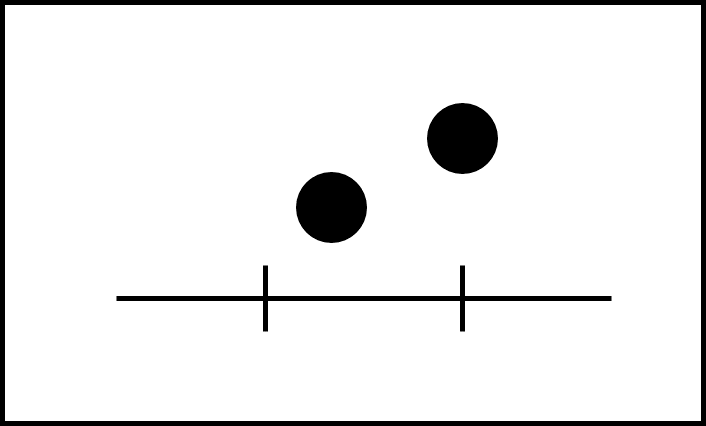

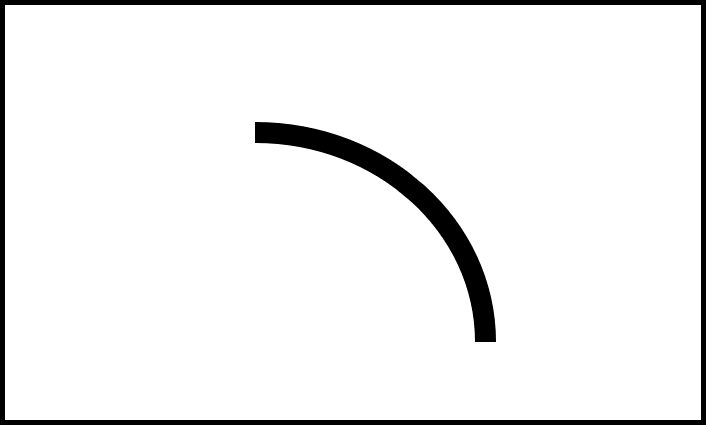

Use this list of visual properties to label the figures below3.

- Position on a common scale

- Position on non-aligned scales

- Length

- Direction

- Angle

- Size (Area)

- Size (Volume)

- Curvature

- Shading (black, white, and gray)

- Color

| Visual Property Number | Visual Property Picture |

|---|---|

| 10 | Figure 2.1 |

| 5 | Figure 2.2 |

| 1 | Figure 2.3 |

| 8 | Figure 2.4 |

| 9 | Figure 2.5 |

| 6 | Figure 2.6 |

| 4 | Figure 2.7 |

| 2 | Figure 2.8 |

| 3 | Figure 2.9 |

| 7 | Figure 2.10 |

Common chart types and their components

Spend three minutes with your neighbor talking about chart types you often see and which graphical elements and/or visual properties they include. Share your answers in the shared document.

Some possible answers to this discussion include:

- Scatter chart: points on one or more scales

- Bar chart: length, area, shading or color

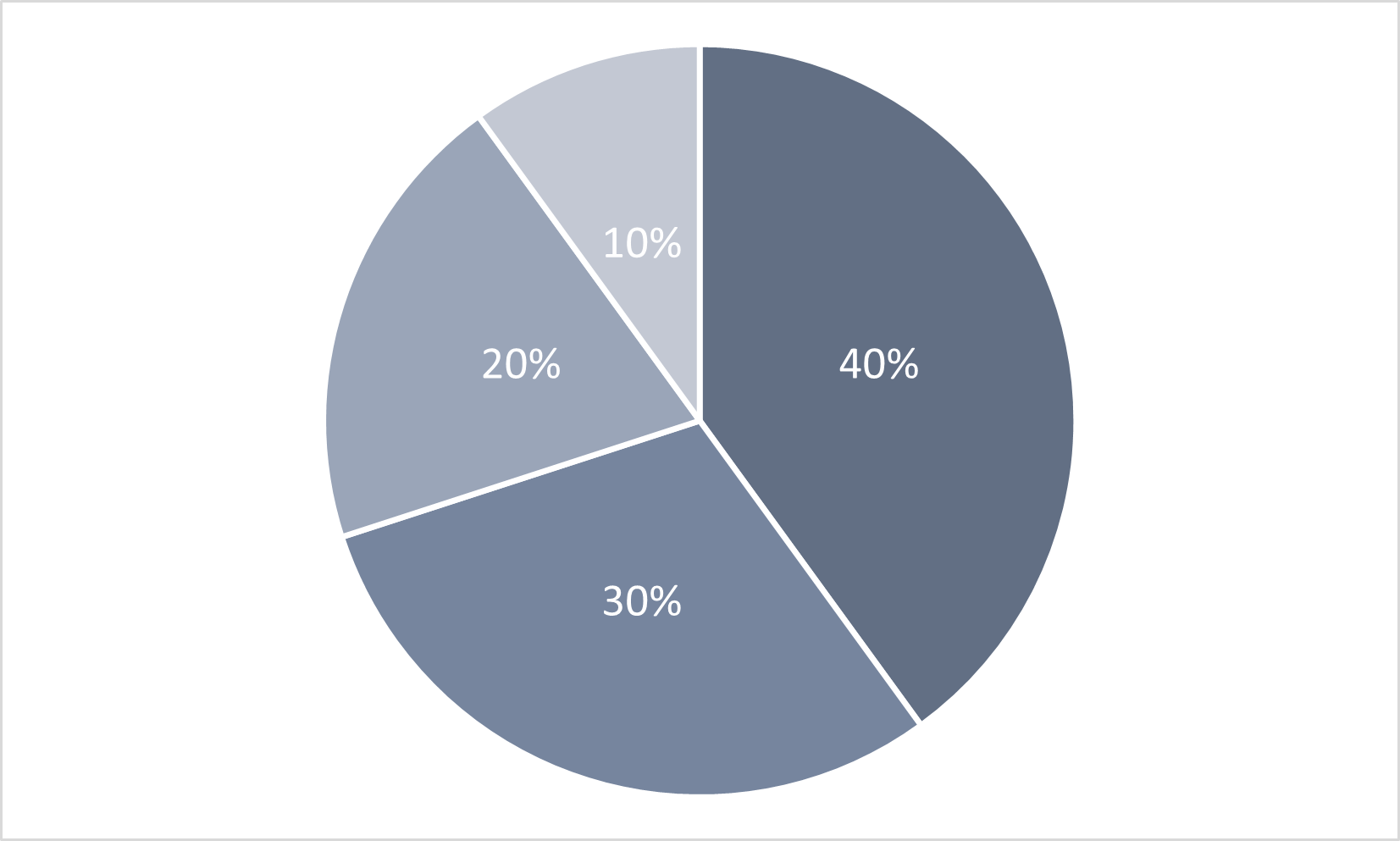

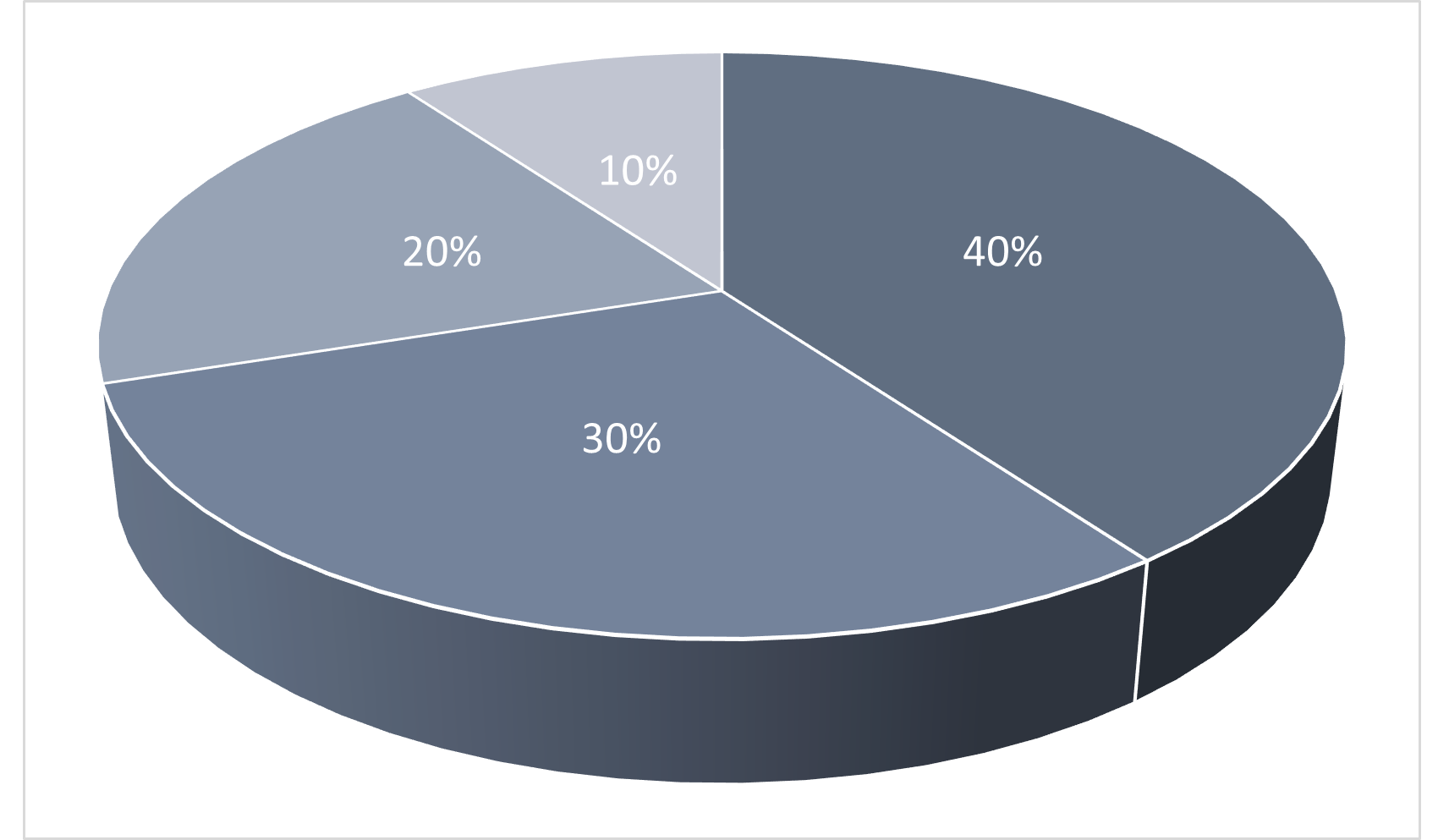

- Pie chart: angle, curvature, area, shading or color

Spreadsheet programs and other software can turn most two-dimensional charts into three-dimensional charts. Use examples such as three-dimensional pie and bar charts to incorporate volume into this discussion.

Better visual representations

Depicting information visually is as much art as science, but some research-backed guidelines can help us design a chart that is easier for people to perceive accurately. These guidelines are the result of experiments conducted by two statisticians in the 1980s4. Despite their study’s limitations, the guidelines they produced remain useful and inform modern guidance about designing charts5.

These guidelines help us understand and categorize graphical elements and visual properties in terms of “better” and “worse” depictions of the underlying data:

- “Better” means easier to perceive accurately

- “Worse” means more difficult to perceive accurately

Graphical Elements

- Points are better than lines

- Lines are better than area (two-dimensional shape)

- Area (two-dimensional shape) is better than volume (three-dimensional shape)

Visual Properties

| Graphical element | Better | Worse |

|---|---|---|

| Points | Position on common scale | Position on non-aligned scales |

| Lines | Length, Direction, Angle | Curvature |

| Shapes | Area | Volume |

Shading and color are special cases

Shading and color can be both better and worse, depending on how they are used in a chart.

Some better uses:

- Differentiate categories or other non-numeric data using a graduated scale or contrasting colors

- Draw attention to areas of a chart that most clearly represent patterns or relationships in the data

Some worse uses:

- Muddle categories by using colors that are too similar

- Distract from a chart’s message by using too many colors or having no clear purpose for the chosen color or shading

We need to ask some questions when including shading or color in a chart:

- How many categories am I working with?

- Are my colors accessible?

- What assumptions are my colors making?

- How will my chart be distributed?

ColorBrewer 2.0 is an online tool for testing color schemes against various conditions. The tool targets cartography but is useful for choosing colors for any kind of data.

With enough time, you may choose to structure the questions about shading and color as a discussion or brainstorm in the shared document. Some rationale for each question is included below.

- How many categories am I working with?

- Using color to differentiate more than 4-5 categories can make the colors too similar to each other.

- Are my colors accessible?

- Color blindness can affect how people perceive certain colors and color combinations, e.g.: red/green and blue/yellow.

- People with visual impairments have difficulty perceiving low-contrast colors.

- What assumptions are my colors making?

- Relying on specific contrasting colors, e.g.: red/green or red/yellow/green, to communicate a message assumes that the colors mean the same thing to your audience that they do to you.

- How will my chart be distributed?

- Printing and photocopying can distort or erase gray and color tones.

- Monitors and projectors cannot always replicate color accurately.

Support your chart’s message

Remember

The purpose of a chart is to communicate a message about patterns or relationships present in the data.

“Better” and “Worse” are comparative states. There is no one best or worst way to communicate a message about a relationship or pattern in a set of data. Instead, we can focus on designing better charts - charts that use components that are easier to perceive accurately.

Better charts can help our audience understand our message and support their decision-making with reliable information.

Worse charts - charts designed using components that are more difficult to perceive accurately - can obscure our message and misinform our audience.

Depending on time and your learners’ interest, this definition of worse charts can be a place to point out that charts that deliberately obscure a message or mislead an audience often include multiple components that are more difficult to perceive accurately. Learners can use this knowledge to bring a critical lens to charts they come across in ordinary life.

Challenge: Practice choosing better charts

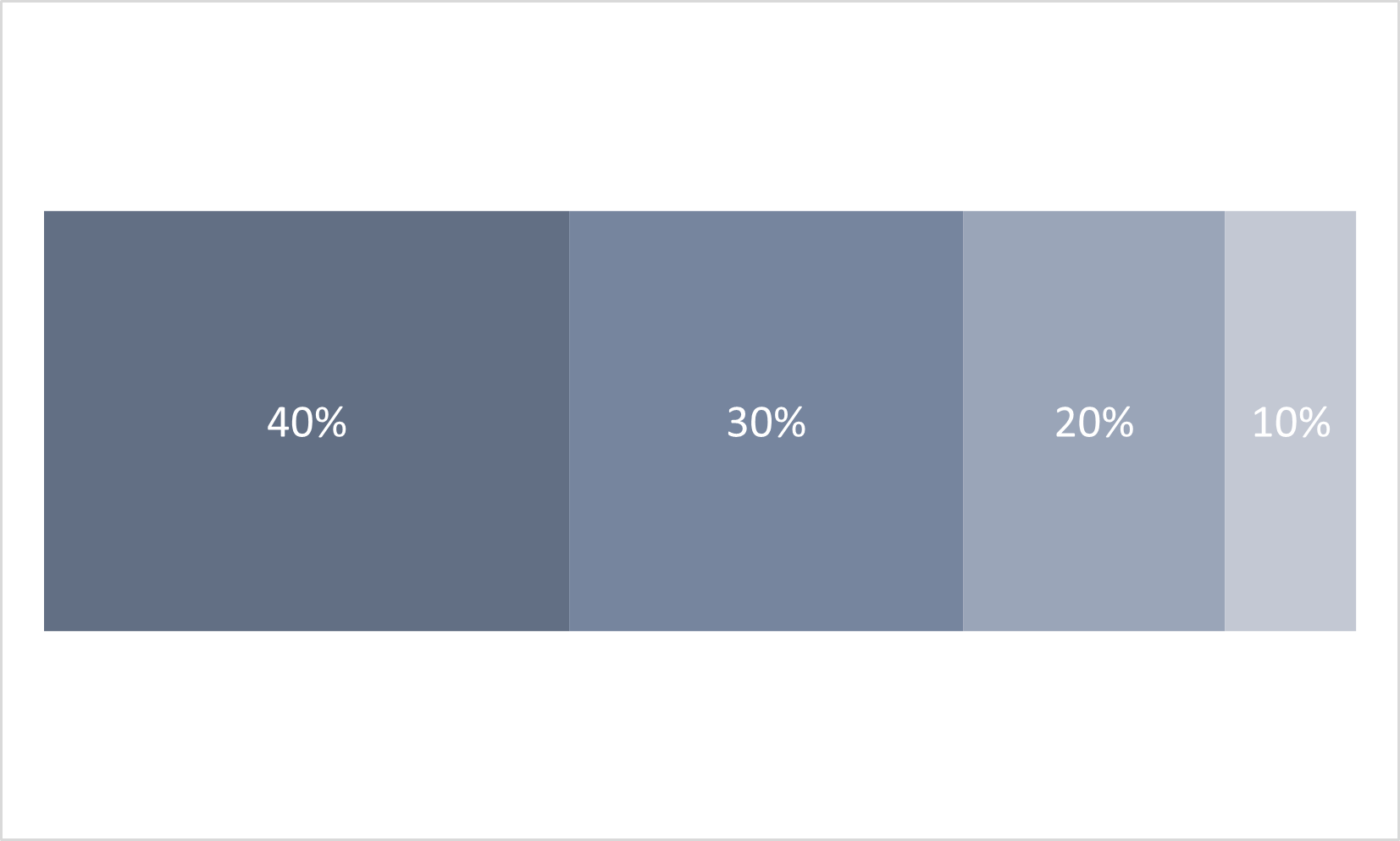

Based on what you just learned about how different visual properties can be better or worse at facilitating accurate perception, look at the chart use cases below. For each chart use case, put the example charts in order from better to worse.

In order from better to worse, the charts are:

- Figure 2.13: 100% Bar Chart

- Figure 2.11: 2D Pie Chart

- Figure 2.12: 3D Pie Chart

Depending on how much experience you’ve had with charts, your perception of which chart style is easiest to understand may differ from the advice on visual properties discussed above.

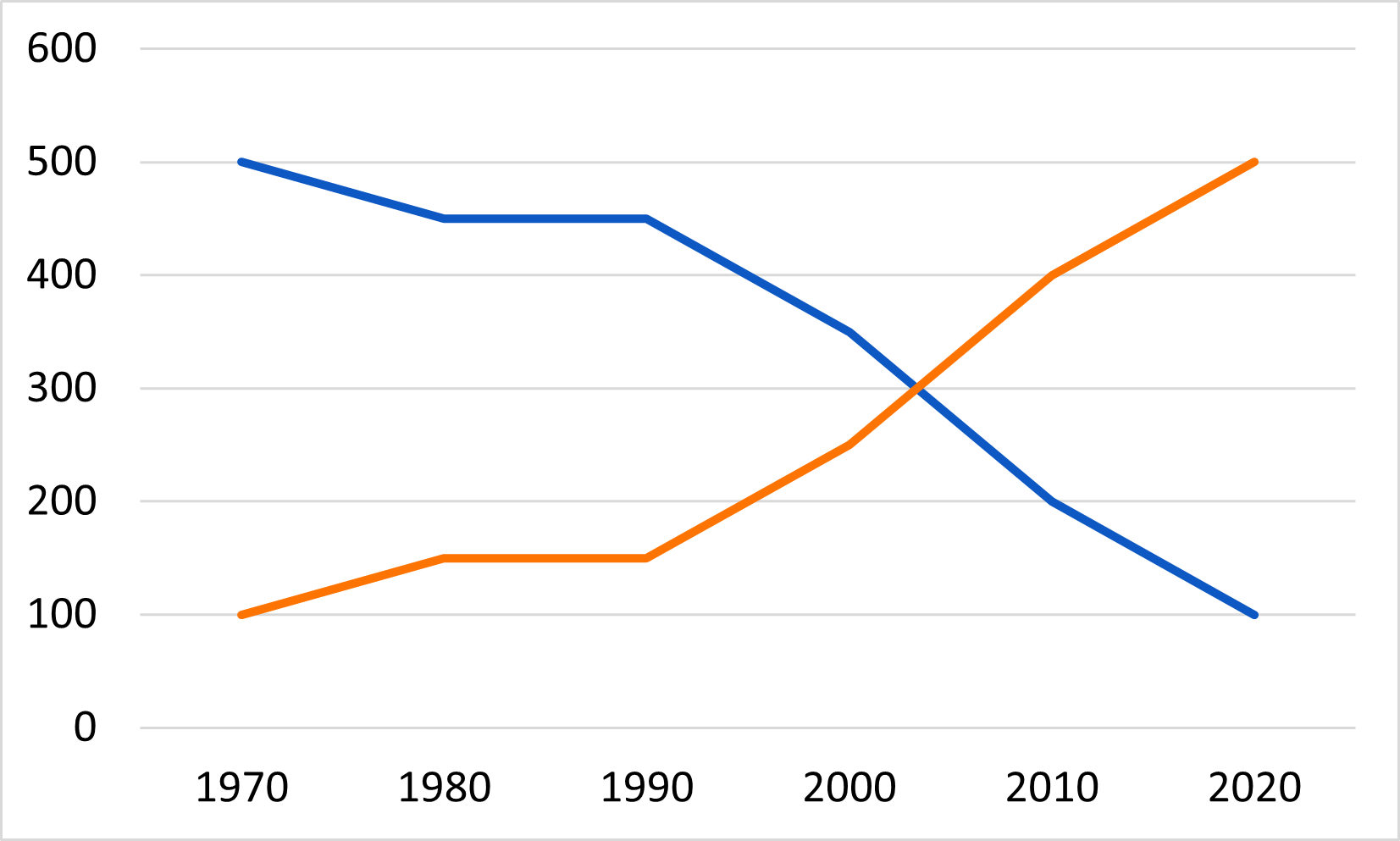

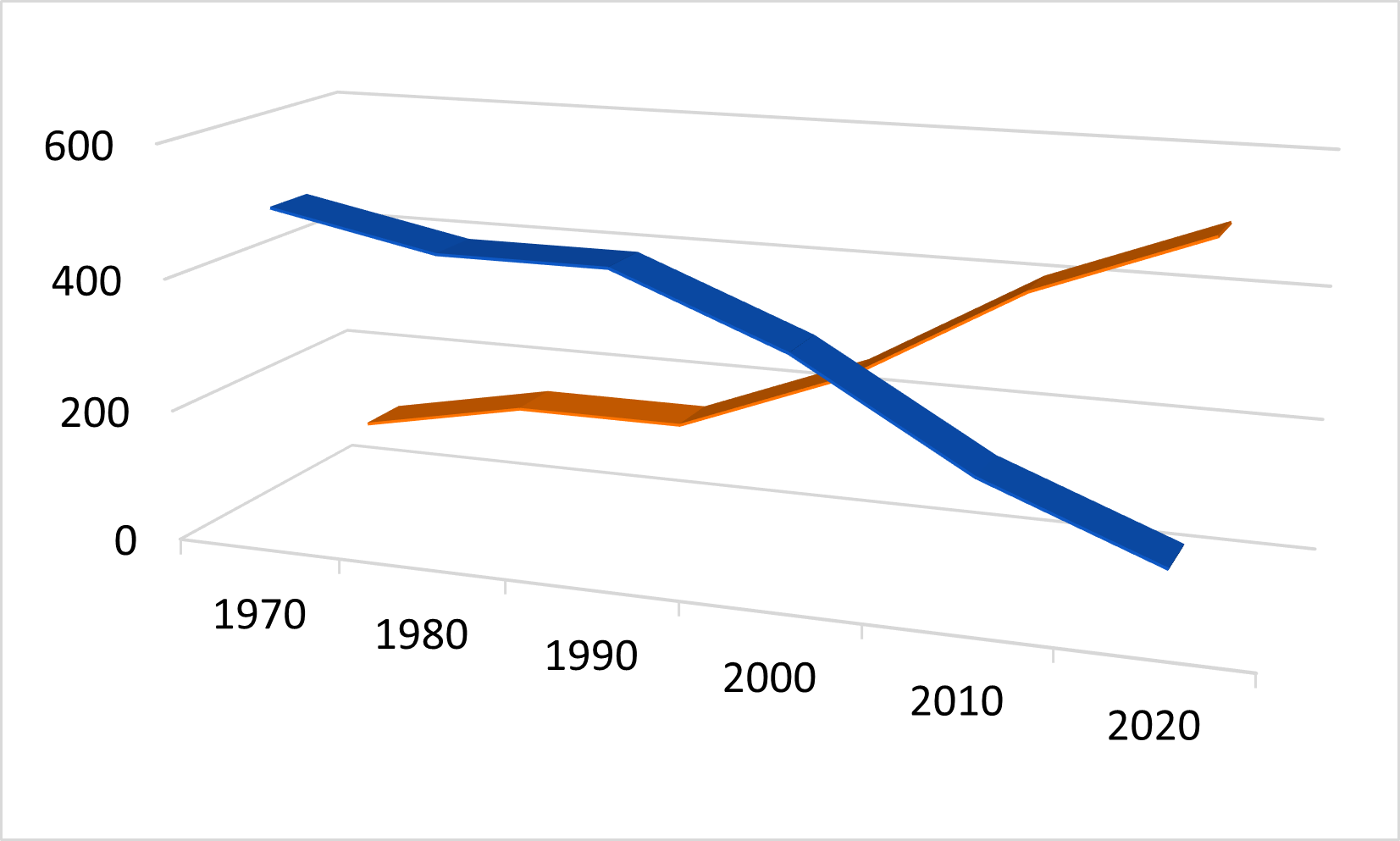

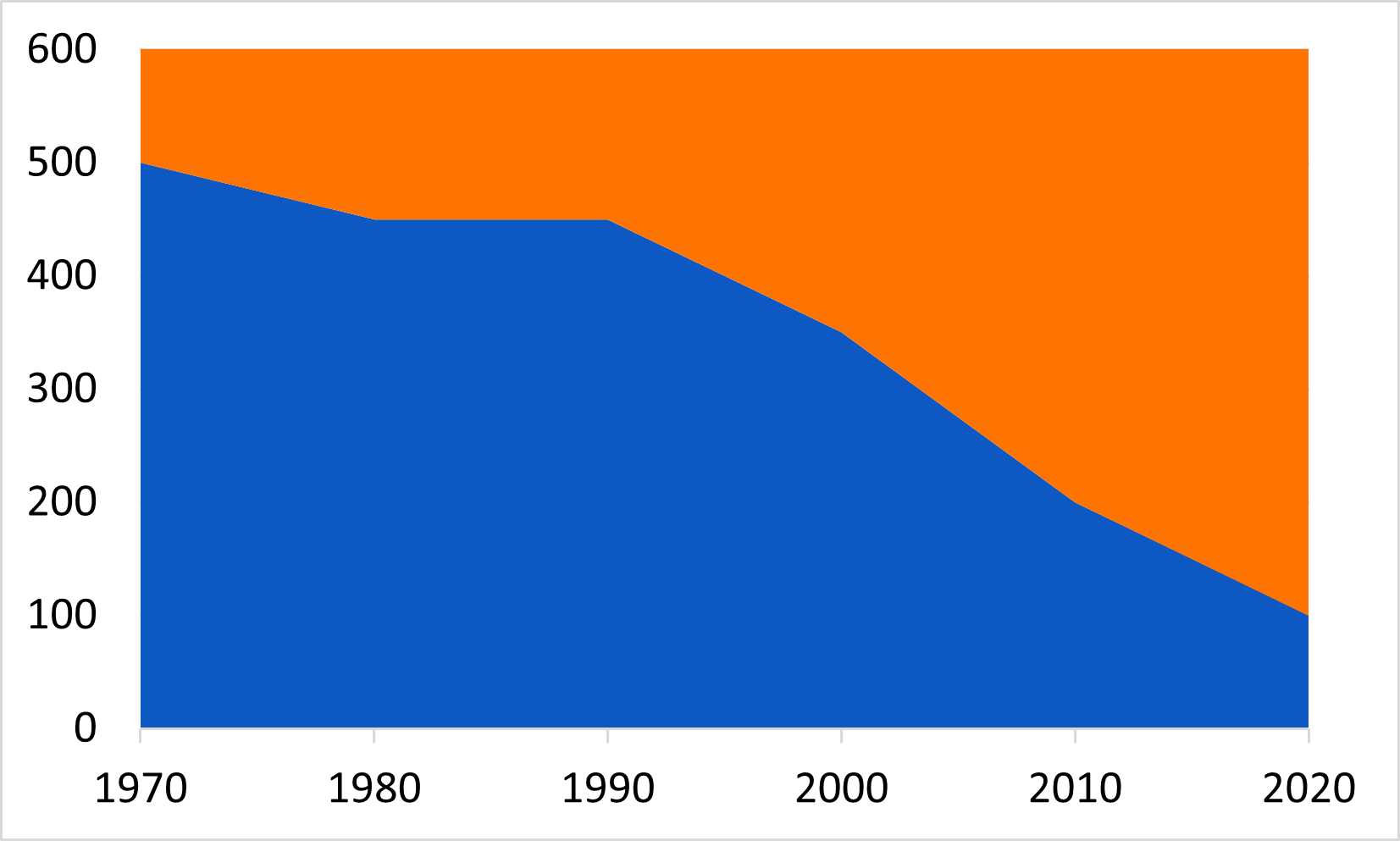

Chart Use Case 2

A chart that compares two categories over a period of time.

In order from better to worse, the charts are:

- Figure 2.14 2D Line Chart

- Figure 2.16 2D Area chart

- Figure 2.15 3D Line Chart

Depending on how much experience you’ve had with charts, your perception of which chart style is easiest to understand may differ from the advice on visual properties discussed above.

To wrap up the challenge, have learners share whether and how their opinions about the charts in the two use cases differ from the advice on visual properties discussed in the lesson. This can happen in the shared document or aloud during a brief discussion of the solutions. The correct answers correspond to the information in the section, “Better Visual Representations.” Any points of disagreement are good places to reinforce that:

- Data visualization is both art and science.

- Previous experience with reading charts can influence which chart

styles we expect for communicating specific kinds of information.

- For example, pie charts are often used to communicate part/whole information, but they may not be better for accurate perception, especially for many parts of one whole.

- There are four graphical elements that can represent data on a chart. The appearance of these elements can be modified with any of ten possible visual properties.

- Research suggests that many people can evaluate some of these visual representations more quickly and with more accuracy than others.

- Visual representations that are easier to perceive accurately support a chart’s message.

- Visual representations that are more difficult to perceive accurately obscure a chart’s message.

Bertin, J. (1981). Graphics and graphic information-processing (W. J. Berg & P. Scott, Trans.). de Gruyter.↩︎

Cleveland, W. S., & McGill, R. (1984). Graphical perception — Theory, experimentation, and application to the development of graphical methods. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 79(387), 531–554. https://doi.org/10.2307/2288400↩︎

Images in this challenge adapted under a CC-BY-4.0 license from Briney, K. (2017). “Data Visualization Camp Instructional Materials (2017)” University of Wisconsin Milwaukee Libraries Instructional Materials. https://dc.uwm.edu/lib_staff_files/4↩︎

Cleveland, W. S., & McGill, R. (1984). Graphical perception — Theory, experimentation, and application to the development of graphical methods. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 79(387), 531–554. https://doi.org/10.2307/2288400↩︎

Evergreen, S. D. H. (2017). Effective data visualization: The right chart for the right data. Los Angeles: SAGE.↩︎