Course introduction

Last updated on 2025-06-24 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is open and reproducible research?

- Why are these practices important, in particular in the context of software used to support such research?

Objectives

- Describe the principles of open and reproducible research and why they are of value in the research community

- Explain how the concept of reproducibility translates into practices for building better research software

- Setup machine with software and data used to teach this course

Software is fundamental to modern research - some of it would even be impossible without software. From short, thrown-together temporary scripts written to help with day-to-day research tasks, through an abundance of complex data analysis spreadsheets, to the hundreds of software engineers and millions of lines of code behind international efforts such as the Large Hadron Collider, there are few areas of research where software does not have a fundamental role.

This course teaches good practices and reproducible working methods that are agnostic of a programming language (although we will use Python code in our examples). It aims to provide researchers with the tools and knowledge to feel confident when writing good quality and sustainable software to support their research. Although the discussion will often focus on software developed in the context of research, most of the good practices introduced here are beneficial to software development more generally.

The lesson is particularly focused on one aspect of good (scientific) software development practice: improving software to enhance reproducibility. That is, enabling others to run our code and obtain the same results we did.

Why should I care about reproducibility?

Scientific transparency and rigor are key factors in research. Scientific methodology and results need to be published openly and replicated and confirmed by several independent parties. However, research papers often lack the full details required for independent reproduction or replication. Many attempts at reproducing or replicating the results of scientific studies have failed in a variety of disciplines ranging from psychology (The Open Science Collaboration (2015)) to cancer sciences (Errington et al (2021)). These are called the reproducibility and replicability crises - ongoing methodological crises in which the results of many scientific studies are difficult or impossible to repeat.

Reproducible research is a practice that ensures that researchers can repeat the same analysis multiple times with the same results. It offers many benefits to those who practice it:

- Reproducible research helps researchers remember how and why they performed specific tasks and analyses; this enables easier explanation of work to collaborators and reviewers.

- Reproducible research enables researchers to quickly modify analyses and figures - this is often required at all stages of research and automating this process saves loads of time.

- Reproducible research enables reusability of previously conducted tasks so that new projects that require the same or similar tasks become much easier and efficient by reusing or reconfiguring previous work.

- Reproducible research supports researchers’ career development by facilitating the reuse and citation of all research outputs - including both code and data.

- Reproducible research is a strong indicator of rigor, trustworthiness, and transparency in scientific research. This can increase the quality and speed of peer review, because reviewers can directly access the analytical process described in a manuscript. It increases the probability that errors are caught early on - by collaborators or during the peer-review process, helping alleviate the reproducibility crisis.

However, reproducible research often requires that researchers implement new practices and learn new tools. This course aims to teach some of these practices and tools pertaining to the use of software to conduct reproducible research.

Review the Reproducible Research Discussion for a more in-depth discussion of this topic.

Practices for building better research software

The practices we will cover for building better research software fall into three areas.

1. Things you can do with your own computing environment to enhance the software

- Using virtual development environments ensures your software can be developed and run consistently across different systems, making it easier for you and others to run, reuse, and extend your code.

2. Things you can do to improve the source code of the software itself

- Organising and structuring your code and project directory keeps your software clean, modular, and reusable, enhancing its readability, extensibility, and reusability.

- Following coding conventions and guides for your programming language ensures that others find it easy to read your code, reuse or extend it in their own examples and applications.

- Testing can save time spent on debugging and ensures that your code is correct and does what it is set out to do, giving you and others confidence in your code and the results it produces.

3. Things you can do to make the software easier for other people to use

- Using version control and collaboration platforms like GitHub, GitLab, and CodeBerg makes it easier to share code and work on it together.

- Fostering a community around your software and promoting collaboration helps to grow a user base for your software and contributes to its long-term sustainability.

- Providing clear and comprehensive documentation, including code comments, API specifications, setup guides, and usage instructions, ensures your software is easy to understand, use, and extend (by you and others).

- Accompanying your software with clear information about its licensing terms and how it should be cited ensures that others can reuse and adapt your code with confidence and that you receive credit when they do so.

Challenge

Individually,

- reflect on what practices (and tools) you are already using in your software development workflow,

- list at least 3 new practices or tools that you would like to start employing or using.

Write your reflections in the shared collaborative document.

Our research software project

You are going to follow a fairly typical experience of a new

researcher (e.g. a PhD student or a postdoc) joining a research group.

You were emailed some spacewalks data and analysis code bundled in the

spacewalks.zip archive, written by another group member who

worked on similar things but has since left. You need to be able to

install and run this code on your machine, check you can understand it

and then adapt it to your own project.

As part of the setup for this

course, you may have downloaded or been emailed the

spacewalks.zip archive. If not, you can download it now.

Save the spacewalks.zip archive to your home directory and

extract it - you should get a directory called

spacewalks.

The first thing you may want to do is inspect the content of the code and data you received. We will use VS Code for browsing, inspecting, modifying files and running our code.

VS Code is a very handy tool for software development and is used by

many researchers worldwide. It “understands” the syntax of many

different file types - for example Python, JSON, CSV, etc. - either

natively or via extensions that can be installed. To open our directory

spacewalks in VS Code – go to File -> Open

Folder and find spacewalks.

You may notice that the software project contains:

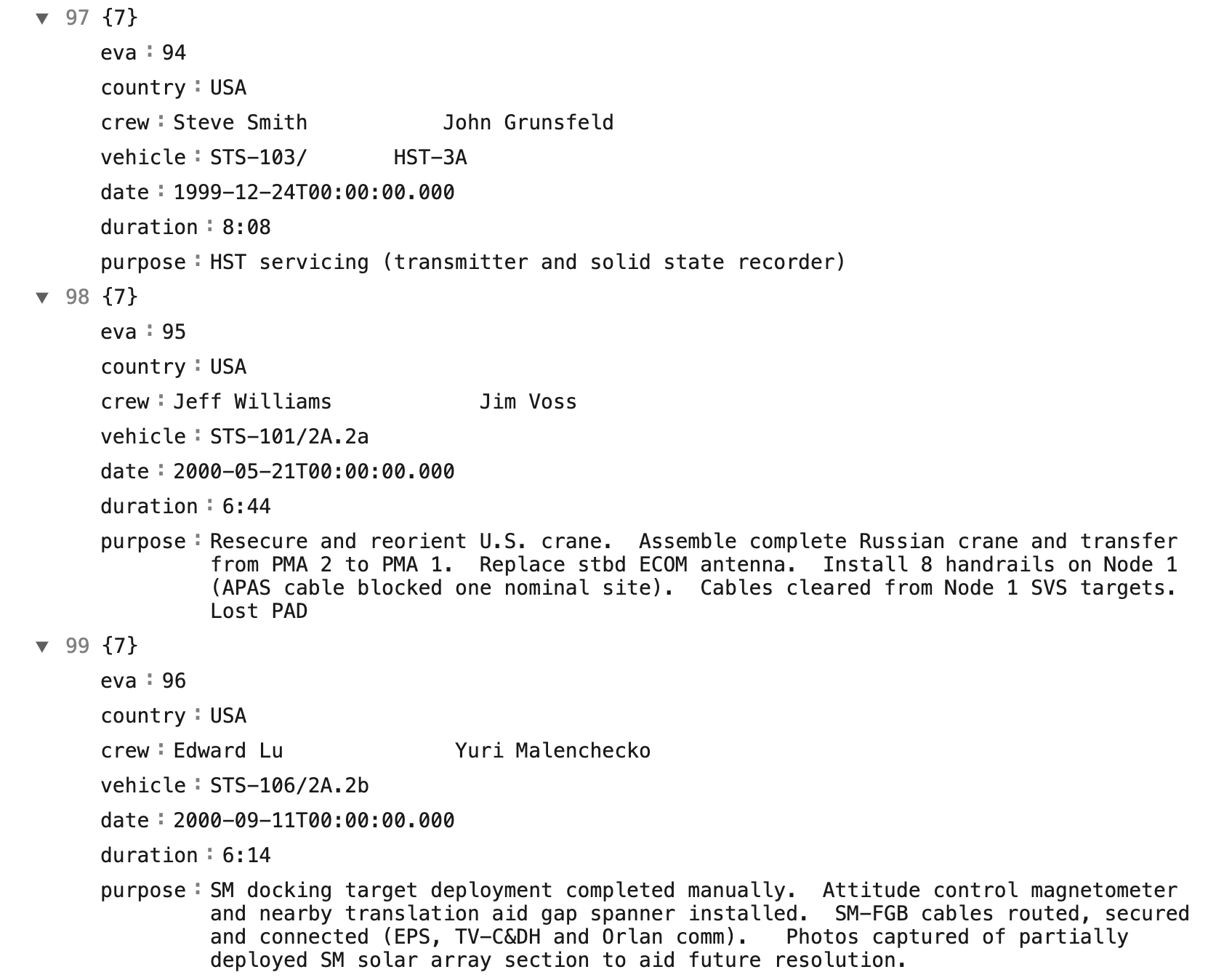

-

A JSON file called

data.json- a snippet of which is shown below - with data on extra-vehicular activities (EVAs, i.e. spacewalks) undertaken by astronauts and cosmonauts from 1965 to 2013 (data provided by NASA via its Open Data Portal). JSON data file snippet showing EVA/spacewalk data including EVA id, country, crew members, vehicle type, date of the spacewalk, duration, and purpose)

JSON data file snippet showing EVA/spacewalk data including EVA id, country, crew members, vehicle type, date of the spacewalk, duration, and purpose) -

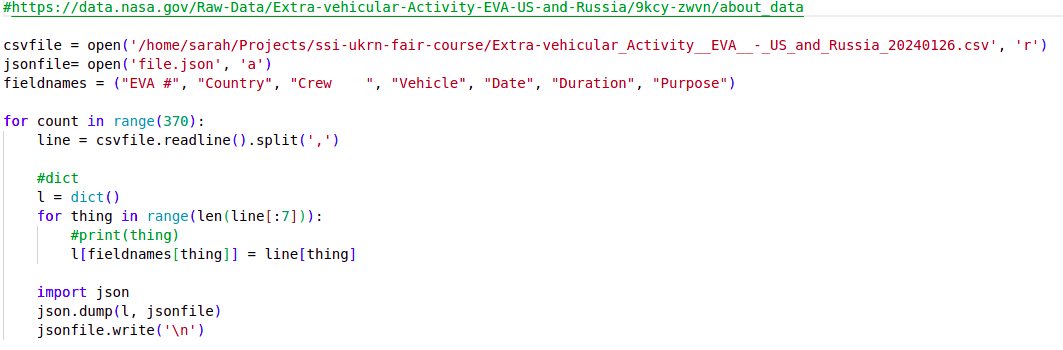

A Python script called

my code v2.pycontaining some analysis code. A first few lines of a Python script

A first few lines of a Python scriptThe code in the Python script does some common research tasks:

- Reads in the data from the JSON file

- Changes the data from one data format to another and saves to a file in the new format (CSV)

- Performs some calculations to generate summary statistics about the data

- Makes a plot to visualise the data

Read and understand data and code

Individually inspect the code and try and see if you can understand what the code is doing and how it is organised.

In the shared document, write down anything that you think is not “quite right”, not clear, is missing, or could be done better.

Below are some suggested questions to help you assess the code. These are not the only criteria on which you could evaluate the code and you may find other aspects to comment on.

- If these files were emailed to you, or sent on a chat platform, or handed to you on a memory stick, how easy would it be to find them again in 6 months, or 3 years?

- Can you understand the code? Does it make sense to you?

- Could you run the code on your platform/operating system (is there documentation that covers installation instructions)? What programs or libraries do you need to install to make it work (and which versions)? Are these commonly used tools in your field?

- Are you allowed to use the code in your own research? If you did, would your collaborators expect credit in some form (paper authorship, citation or acknowledgement)? Are you allowed to edit the files? Publish them? Share them with others?

- Is the code written in a way that allows you to easily modify or extend it? How easy would it be to change its parameters to calculate a different statistic, or run on a different input file?

This is a (non-exhaustive) list of things that could be fixed/improved with our code and data:

File and variable naming

- data (

data.json) and Python script (my code v2.py) files could have more descriptive names - Python script (

my code v2.py) should not contain blank spaces as it may cause problems when running the code from command line - variables (e.g.

w) should have more descriptive and meaningful names - version control is embedded in file name - there are better ways of keeping track of changes to code and its different versions

Code organisation and style

- import statements should be grouped at the top

- commenting and uncommenting code should not be used to direct the flow of execution / type of analysis being done

- the code lacks comments, documentation and explanations

- code structure could be improved to be more modular and not one monolithic piece of code - e.g. use functions for reusable units of functionality

- unused variables (e.g.

fieldnamesmeant to be used when saving data to CSV file) are polluting the code and confusing the person reading the code - spaces should not be used in column names as it can lead to error when reading the data in

Code content and correctness

- fixing the loop to 374 data entries is not reusable on other data files and would likely break if the data file changed

- running the code twice causes the program to fail as the result file from the previous run will exist (which the code does not check for) and the script will refuse to overwrite it

- the code does not specify the encoding when reading the data in, and we are also not sure what encoding the data was saved in originally

- how can we be confident the data analysis and plot that is produced as a result are correct?

documentation

- there is no README documentation to orient the user

- there is no licence information to say how the code can be reused (which then means it cannot be reused at all)

- it is not clear what software dependencies the code has

- there are no installation instructions or instructions on how to run the code

As you have seen from the previous exercise - there are quite a few things that can be improved with this code. We will try to make this research software project a “bit better” for future use.

Let’s check your setup now to make sure you are ready for the rest of this course.

Check your setup

From a command line terminal on your operating system or within VS Code run the following commands to check you have installed all the tools listed in the Setup page and that are functioning correctly.

Checking the command line terminal:

$ date$ echo $SHELL$ pwd$ whoami

Checking Python:

$ python --version$ python3 --version$ which python$ which python3

Checking Git and GitHub:

$ git --help$ git config --list$ ssh -T git@github.com

Checking VS Code:

$ code$ code --list-extensions

The expected out put of each command is:

- Today’s date

-

bashorzsh- this tells you what shell language you are using. In this course we show examples in Bash. - Your “present working directory” or the folder where your shell is running

- Your username

- In this course we are using Python 3. If

python --versiongives you Python 2.x you may have two versions of Python installed on your computer and need to be careful which one you are using. - Use this command to be certain you are using Python version 3, not 2, if you have both installed.

- The file path to where the Python version you are calling is installed.

- If you have more than one version these should be different paths, if both 5. and 6. gave the same result then 7. and 8. should match as well.

- The help message explaining how to use the

gitcommand. - You should have

user.name,user.emailandcore.editorset in your Git configuration. Check that the editor listed is one you know how to use. - This checks if you have set up your connection to GitHub correctly.

If is says

permission deniedyou may need to look at the instructions for setting up SSH keys again on the Setup page. - This should open VSCode in your current working directory. macOS users may need to first open VS Code and add it to the PATH.

- You should have the extensions GitLens, Git Graph, Python, JSON and Excel Viewer installed to use in this course.

Further reading

We recommend the following resources for some additional reading on reproducible research:

- Reproducible research through reusable code is a one day course by the Netherlands eScience Center which discusses similar themes to this course, but in a shorter format.

- The Turing Way’s “Guide for Reproducible Research”

- A Beginner’s Guide to Conducting Reproducible Research, Jesse M. Alston, Jessica A. Rick, Bulletin of The Ecological Society of America 102 (2) (2021), https://doi.org/10.1002/bes2.1801

- “Ten reproducible research things” tutorial

- FORCE11’s FAIR 4 Research Software (FAIR4RS) Working Group

- “Good Enough Practices in Scientific Computing” course

- Reproducibility for Everyone’s (R4E) resources, community-led education initiative to increase adoption of open research practices at scale

- Training materials on different aspects of research software engineering (including open source, reproducibility, research software testing, engineering, design, continuous integration, collaboration, version control, packaging, etc.), compiled by the INTERSECT project

- Curated resources by the Framework for Open and Reproducible Research Training (FORRT)

Acknowledgements and references

The content of this course borrows from or references various work.