Better start with a software project

Last updated on 2026-03-03 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is a version control system?

- Why is version control essential to building good software

- What does a standard version control workflow look like?

Objectives

- Set up version control for our software project to track changes to it

- Create self-contained commits using Git to incrementally save work

- Push new work from a local machine to a remote server on GitHub

In this episode, we will set up our new research software project using some good practices from the start. This will lay the foundation for long-term sustainability of our code, collaboration, and reproducibility.

This starts with following naming conventions for files, employing version control, and (in the next episode) setting up a virtual development environment with software dependencies to ensure the project can be more easily and reliably run, shared and maintained. Next (over the rest of the course) - adding tests, setting up automation (e.g. continuous integration), documenting software and including metadata such as licensing, authorship and citation will ensure the results our software produces can be trusted and others can build upon it with confidence.

Let’s begin by creating a new software project from our existing code, and start tracking changes to it with version control.

From script to software project

In the previous episode you have unzipped spacewalks.zip

into a directory spacewalks in your home directory.

Within the RStudio the files contained within spacewalks

should appear within the Files Tab located

in the bottom-right pane by default.

You can also access files and work within a unix shell Terminal in the terminal tab (Windows users need to make sure that the terminal is “GitBash”; not “PowerShell” or “cmd”). If your terminal tab does not appear to be GitBash, please refer to the installation instructions

Within the terminal tab, if you are not already inside the

spacewalks directory, you can navigate into it and list its

contents. The symbol ~ reprensents your

user’s home directory, and the -F flag

places a forward slash / if the item

listed is a directory. The -a flag will

request to show all files, including hidden files with a name starting

with a dot.

OUTPUT

total 280

drwxr-xr-x@ 8 username staff 256 Oct 30 18:19 ./

drwx------@ 727 username staff 23264 Oct 30 18:18 ../

drwxr-xr-x 4 username staff 128 Oct 30 18:19 .Rproj.user/

drwxr-xr-x@ 4 username staff 128 Oct 14 10:06 astronaut-data-analysis-old/

-rw-r--r--@ 1 username staff 132981 Oct 14 09:58 data.json

-rw-r--r--@ 1 username staff 1762 Oct 14 09:35 my code v2.R

-rw-r--r-- 1 username staff 205 Oct 30 18:19 spacewalks.Rproj(Note: The @ sign within the first

column is only shown for macOS users. This is a special macOS code

signifying that extended attributes exist, which can be seen with

attr filename.)

The directory .Rproj.user/ was created by RStudio when

the project was created in the previous section. Its presence is

revealed by the -a option to show hidden files. In some

cases some other files may appear depending on your OS or other factors:

a file named .DS_Store might be seen by Mac users and can

be ignored for the moment and a file named .Rhistory might

appear as well and can be ignored for now.

Over the rest of the course, we will transform a collection of these files into a well-structured software project that follows established good practices in research software engineering.

The first thing you may notice that our software project contains

folder astronaut-data-analysis-old which presumably tries

to keep track of older versions of the code. There is a better way to do

that using version control tool, such as Git, and we can delete this

folder but will wait until after we set up our version control with git.

This way we can keep that version in our history and can delete it so it

isn’t currently in our folder.

Version control

Before we do any further changes to our software, we want to make sure we can keep a history of what changes we have done since we inherited the code from our colleague.

We can track changes with version control. Later on, we will store those changes on a remote server too – both for safe-keeping and to make those changes easier to share with others. In later episodes, we will also see how version control makes it easier for multiple collaborators to work together on the same project at the same time and combine their contributions.

Version control refresher

What is a version control system?

Version control systems are tools that let you track changes in files over time in a special database that allows users to “travel through time”, and compare earlier versions of the files with the current state. Think of a version control system like turning on ‘Track Changes’ on Microsoft Word/Google Docs, but for any files you want, and a lot more powerful and flexible.

Why use a version control system?

As scientists, our main motivation for using version control is reproducibility. By tracking and storing every change we make, we can restore our project to the state it was at any point in time. This is incredibly useful for reproducing results from a specific version of the code, or tracking down which changes we (or others) made introduced bugs or changed our results.

The other benefit of version control is it provides us with a history of our development. As we make each change, we record what it was, and why we made it. This helps make our development process transparent and auditable – which is a good scientific practice.

It also makes our project more sustainable - as our data, software and methods (knowledge) remain usable and accessible over time (especially if made available in shared version controlled code repositories), even after the original funding ends or team members move on.

Git version control system

Git is the most popular version control system used

by researchers worldwide, and the one we’ll be using. Git is used mostly

for managing code when developing software, but it can track

any files – and is particularly effective with text-based files

(e.g. source code like .py, .c,

.r, but also .csv, .tex and

more).

Git helps multiple people work on the same project (even the same file) at the same time. Initially, we will use Git to start tracking changes to files on our local machines; later on we will start sharing our work on GitHub allowing other people to see and contribute to our work.

Git refresher

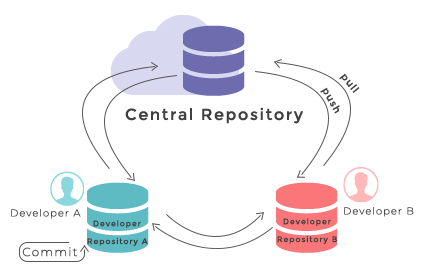

Git stores files in repositories - directories where changes to the files can be tracked. The diagram below shows the different parts of a Git repository, and the most common commands used to work with one.

-

Working directory - a local directory (including

any subdirectories) where your project files live, and where you are

currently working. It is also known as the “untracked” area of Git. Any

changes to files will be marked by Git in the working directory. Git

will only save changes that you explicitly tell it to. Using

git add FILENAMEcommand, can you tell Git to start tracking changes to fileFILENAMEin your working directory. -

Staging area (index) - once you tell Git to start

tracking changes to files (with

git add FILENAMEcommand), Git saves those changes in the staging area on your local machine. Each subsequent change to the same file needs to be followed by anothergit add FILENAMEcommand to tell Git to update it in the staging area. To see what is in your working directory and staging area at any moment (i.e. what changes is Git tracking), you can run the commandgit status. The staging area lets you bundle together groups of changes to save to your repository. -

Local repository - stored within the

.gitdirectory of your project locally, this is where Git wraps together all your changes from the staging area and puts them using thegit commitcommand. Each commit is a new, permanent snapshot (checkpoint, record) of your project in time, which you can share or revert to. -

Remote repository - this is a version of your

project that is hosted somewhere on the Internet (e.g., on GitHub,

GitLab or somewhere else). While your project is nicely

version-controlled in your local repository, and you have snapshots of

its versions from the past, if your machine crashes you still may lose

all your work. Plus, sharing or collaborating on local work with others

requires lots of emailing back and forth. Working with a remote

repository involves ‘pushing’ your local changes to it (using

git push), and pulling other people’s changes back to your local copy (usinggit fetchorgit pull). This keeps the two in sync in order to collaborate, with a bonus that your work also gets backed up to another machine. Best practice when collaborating with others on a shared repository is to always do agit pullbefore agit push, to ensure you have any latest changes before you push your own.

Start tracking changes with Git

Before we start, if you forgot to do it during setup, tell Git to use

main as the default branch. More modern versions of Git use

main, but older ones still use master as their

main branch. They work the same, but we want to keep things consistent

for clarity.

At this point, we should be located in our spacewalks

directory. We want to tell Git to make spacewalks a

repository – a directory where Git can track changes to our files. We

initialize this new repository with:

This repository just created is “hidden” as it starts with a dot. We can find its name with the same list command used previously:

A new line will be visible in the output:

OUTPUT

drwxr-xr-x 9 username staff 288 Oct 30 18:21 .git/We can see that its name is .git and

the trailing slash confirms that it is a directory into which the Git

software will write.

We can check everything is set up correctly by asking Git to tell us the status of our project:

OUTPUT

On branch main

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

.Rproj.user/

astronaut-data-analysis-old/

data.json

my code v2.R

spacewalks.Rproj

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)This tells us that Git has noticed two files in our directory, but unlike Dropbox or OneDrive, it does not automatically track them. We need to tell Git explicitly which files we want it to track. This is not a handicap, but rather helpful, since scientific code can have vast inputs or outputs we might not want Git to track and store (GBs to TBs of space telescope data) or require sensitive information we cannot share (for example, medical records). This is not a problem, but rather a helpful feature, since scientific code can have vast inputs or outputs we might not want Git to track and store (GBs to TBs of space telescope data) or require sensitive information we cannot share (for example, medical records). Before we commit this initial version, we should try to run it. This is often the first thing you might do upon receiving someone’s code.

There are multiple ways to run R code:

Option 1: within R console

- Click once on the file

my code v2.Rwithin the Files Tab. This will open the file in the top left quadrant. - Then click on the “Source” icon located at the top

right of the opened file. Note, there are two options - “Source”, which

is equivalent to running

source('my code v2.R')and “Source with Echo”, which is equivalent to running the script line by line. Be aware, if you have objects in your environment, this may effect how your script runs.

Option 2: from the Terminal tab

- An R script can be run within the shell with command

Rscriptwhich is part of any R installation. - The command is all uppercase and blank spaces in the file name have to be escaped by a backslash as shown:

Option 2: from the Shell window

- An R script can be run within the shell with command

Rscriptplus the path to the R file we want to run. which is part of any R installation. For example:

OUTPUT

Error in open.connection(con, "rb") : cannot open the connection

Calls: read_json ... parse_and_simplify -> parseJSON -> parse_con -> open -> open.connection

In addition: Warning message:

In open.connection(con, "rb") :

cannot open file '/home/sarah/Projects/astronaut-analysis/data.json': No such file or directory

Execution haltedWe get this error because the paths to the data files have been hard coded as absolute paths for the original developer’s machine. Hard-coding paths is not very reproducible, as it means the paths need to be changed whenever the code is run on a new computer. Instead, we will soon change the code to use the relative paths within the project structure and eventually we will change the code to take in arguments from the command line when it is run. When we commit the files, we will note that the code is broken in our commit message. This is a best practice if you decide to commit broken code.

Add files into repository

Befgore proceeding let’s display once more the files as Git sees them:

From this point we are going to start tracking files with Git. We can

tell Git to track a file using git add.

First lets make a commit with our old analysis files and then we can delete them

Then we can delete the old analysis folder. To delete the file on our

filesystem and in the git repo at the same time we can use

git rm

Note: we had to use the -r flag to delete the whole

folder. Be careful when deleting whole folders. Though we can be fairly

confident in this deletion since we know it is also already version

controlled with git and we could get it back if needed.

Let’s look at what the status of the deletion is and be sure we aren’t deleting any extra files.

OUTPUT

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

deleted: astronaut-data-analysis-old/code.R

deleted: astronaut-data-analysis-old/Extra-vehicular_Activity__EVA__-_US_and_Russia_20240126.csv

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

.Rproj.user/

data.json

my code v2.R

spacewalks.RprojNow we will commit the deletion

Next we can add our current workings scripts and data. We also add

the project file spacewalks.Rproj.

and then check the right thing happened:

OUTPUT

On branch main

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: data.json

new file: my code v2.R

new file: spacewalks.Rproj

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

.Rproj.user/Git now knows that we should track the changes to files

my code v2.R and data.json, but it has not

‘committed’ those changes to the record yet.

When we are sure that we want to proceed, we can commit the

changes with a git commit command usually referred to as “a

commit”.

A commit is a snapshot of how your tracked files have changed at this moment in time, which is referred to as a “stage”, “a moment in time.” To create a commit that records the fact that we added two new files, we need to run one more command.

The following is a multiline commit as the double quote is not closed

at the end of the first line. As you press Enter or Return, you will see

a temporary prompt: dquote> which simply means that more

text can be entered on this and perhaps more lines until the double

quote is closed on the last line.

BASH

$ git commit -m "Add the initial spacewalks data and code

BREAKING CHANGE: Path to data is hard coded and needs to be fixed"OUTPUT

[main (root-commit) bc5252e] Add the initial spacewalks data and code

3 files changed, 461 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 data.json

create mode 100644 my code v2.R

create mode 100644 spacewalks.RprojAt this point, Git has recorded the changes for the files we asked to

be tracked when we issued the command git add. The changes

from the older to the new file versiosn are saved within the

.git/ as a snapshot which could be retried at a

later date. This is called a commit (or revision).

The -m option means message, and records a short,

descriptive, and specific comment that will help us remember later on

what we did and why. If we run git commit without

-m , Git will still expect a message – and will launch a

text editor so that we can write a longer one. The editor will depend on

settings and operating system.

Remember, good commit messages start with a brief (<50 characters) statement about the changes made in the commit. Generally, the message should complete the sentence “If applied, this commit will…”. If you want to go into more detail, add a blank line between the summary line and your additional notes. Use this additional space to explain why you made changes and/or what their impact will be.

If we run git status now, we see:

OUTPUT

On branch main

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

.Rproj.user/

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)You may see one or more hidden files or directries (starting with a

dot) that are not tracked. To avoid seeing the “Untracked files” message

every time we’ll create a special text file called

.gitignore to list these files. RStudio automatically

creates one for you when you set up the project with git from the

beginning, in which case you can see its content with command

cat .gitignore. But let’s learn how to do this now.

The method that does not need any special editing software is via the

shell, thanks the echo command and the power of

redirection. We can use a single “>” to create the file. Note that if

the .gitignore file already was present, this command would

erase the content of the original. For the same reason any future

additions with echo need two >> to add (i.e. append)

to the file without overwriting it.

You might find github’s collection of gitignore templates helpful for common coding projects.

If you issue a git status at this point Git will let you

know that wealso need to track itself:

OUTPUT

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

new file: .gitignoreWe still need to commit that change:

OUTPUT

[main c9bde81] add .gitignore

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 .gitignoreA final status check will let us know that we are up to date on all fronts.

OUTPUT

On branch main

nothing to commit, working tree cleanThis is the procedure we’ll continue to follow: make changes,

thenadd to move the changes to staging, then

commit to save this version of our repo, then

status to check everything is in the state we expect.

Where are my changes?

If we run ls at this point, we’ll still only see two

files – our script, and our dataset. Git saves information about our

files’ history in the special .git directory mentioned

earlier. This both stops our folders being cluttered with old versions,

and also stops us accidentally deleting them!

You can see the hidden Git directory using the -a flag

to show all files and folders:

OUTPUT

.

..

.git/If you were to delete .git, your directory would stop

being a repository, and it would lose all of your history of changes.

You never need to look into .git yourself – Git adds useful

commands to do that, which are covered later on.

Make a change

You may have noticed that the script we received contains blank

spaces in its filename. This meant that, when we were typing the

script’s name into the terminal, we had to add a slash before the space

like this: my\ code\ v2.R. Using a backslash in this way is

called “escaping”. It lets the terminal know to treat the space as part

of the filename, and not split the name into separate, independent

arguments. It is a bit inconvenient and will cause errors or problems if

you forget. Therefore, the best practise is to completely avoid spaces

in filenames as well as directories. The simplest fix is to replace the

spaces with underscores _ instead.

To change the name of the file, it is judicious to use the Git

command git mv rather than the mv shell

command:

If you run git status again, you’ll see Git has noticed

the change in the filename. Note, git mv handles the name

change directly, instead of seeing a deleted file and a new file as

would be the case if we’d used mv and then

git add. It also stages the changes to be committed.

OUTPUT

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

renamed: my code v2.R -> my_code_v2.ROUTPUT

[main 9445e74] removed spaces from filename

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

rename my code v2.R => my_code_v2.R (100%)Rename our data and output files

Now that we know how to rename files in Git, we can use it to make our files and code a bit easier to understand.

We may want to:

- Give our script and input data file more meaningful names, e.g

eva_data_analysis.Randeva-data.json. This change also removes version tracking from the old script name as we are using Git for version control, and Git will keep track of that for us. - Choose informative file names for our output data file

(e.g.

eva-data.csv) and plot (cumulative_eva_graph.png). - Use relative paths (e.g.

./eva-data.json) instead of absolute paths (e.g.home/sarah/Projects/astronaut-analysis/data.csv) to the files (which were hardcoded to the path on our colleagues machine and would not work on ours). - Update the R script with these changes.

Update the filenames in the repo

Try to make these changes yourself.

- Give our R script and input data file informative names -

eva_data_analysis.Randeva-data.json, respectively. - Update other file names and paths used in the script - output CSV

data (

eva-data.csvto match the new input data name) and plot(cumulative_eva_graph.png). - Stage and commit these changes in the Git repository.

Firstly, let’s update the file names in our R script in RStudio:

R

data_f_file = 'eva-data.json'

data_t_file = 'eva-data.csv'

g_file = 'cumulative_eva_graph.png'

Save the file after changes are implemented.

Next, we need to rename the files on the file system using Git and

commit all changes. Since we used git mv we don’t need to

use add:

This will show the fact that we changed the file name and made changes in its content (i.e. the paths for files.)

OUTPUT

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

renamed: data.json -> eva-data.json

renamed: my_code_v2.R -> eva_data_analysis.R

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: eva_data_analysis.R(Untracked files are omitted for clarity.)

Note that we modified eva_data_analysis.R in addition to

renameing it. We can add those changes to the stage as well as part of

this commit or commit them separately. In this case, we will go ahead

and stage them together.

Finally, we can commit our changes:

OUTPUT

[main 692b680] Implement informative file names and script editing

2 files changed, 3 insertions(+), 3 deletions(-)

rename data.json => eva-data.json (100%)

rename my_code_v2.R => eva_data_analysis.R (91%)Is the code working now?

The code failed because the file name paths did not match as it was hard-coded to a specific user. We just updated the file name paths with the hope that the code will work as . But is it?

Try to run the code now as before, either with RStudio or with the

Rscript command on the shell terminal:

RStudio: click the “source” button as in Option 1 above.

Shell terminal: use the command

In both cases there will be another error:

OUTPUT

Error in Date() : could not find function "Date"Challenge

- Where in the code is the problem? Which line?

- Is there a way to find help with the error information?

- The error appears on the line with the command

date = Date()which is on line 24 - We can ask for help easily in RStudio with

??Datewhich will show 7 “Vignettes” entries. - In the Shell Terminal the command would be:

Rscript -e "??Date"(and typeqto quit afterwards.)

But which Vignette can help us?

If we look 2 lines below the error line in

eva_data_analysis.R , we can note that the line

library(lubridate) calls a name that matches a Vignette. It

seems that the function Date() was called before the

library was requested.

Therefore, the solution is to move library(lubridate) at

least above the date=-Date() code line. While this should

work, it may be judicious to place the library command at

the top of the script.

Let’s edit the file again: place library(lubridate) one

line above date = Date()

Then run the code with either RStudio or Rscript. The

code should now run its course without error.

Code output

We can now better understand the purpose of the code which is to create a plot using the provided data. The result is both a PNG file saved in the current directory, and the display of the same plot within the Rstudio panel “Plots” tab in the botton right panel.

If you ran the Rscript command, the display is

automatically converted into a PDF file called Rplots.pdf

because the default plotting device is a pdf instead of the plotting

viewer as above. In both cases the file

cumulative_eva_graph.png is also saved.

OUTPUT

-rw-r--r-- 1 username staff 22883 Nov 4 13:03 Rplots.pdf

-rw-r--r-- 1 username staff 27605 Nov 4 13:03 cumulative_eva_graph.png

-rw-r--r--@ 1 username staff 1710 Nov 4 13:02 eva_data_analysis.R

-rw-r--r--@ 1 username staff 257 Nov 4 12:43 spacewalks.Rproj

-rw-r--r--@ 1 username staff 132981 Oct 14 09:58 eva-data.jsonWe can therefore save the changes with Git as before:

Then add the new or modified files. Based in how you ran the code you

might not have a PDF file. If you are on a Mac the file

.DS_Store may have now appeared, so add it.

BASH

$ git add eva_data_analysis.R cumulative_eva_graph.png Rplots.pdf .DS_Store

```bash

```bash

git commit -m "fixed code and saving output files"[main 0e65c91] fixed code and saving output files

4 files changed, 4 insertions(+), 4 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 .DS_Store

create mode 100644 Rplots.pdf

create mode 100644 cumulative_eva_graph.pngOn branch main

nothing to commit, working tree cleanInteracting with a remote Git server

Git is distributed version control system and lets us synchronise work between multiple copies of the same repository - which may not be on your machine (called remote repositories). So far, we have used a local repository on our machine and, even though we have been incrementally saving our work in a way that is recoverable, if we lost our machine then we would lose all our code along with it,

Fortunately, we can easily upload our local repository, with all our code and the history of our development, to a remote server so that it can be backed-up and recovered in future.

GitHub is an online software development platform that can act as a central remote server. It uses Git, and provides facilities for storing, tracking, and collaborating on software projects. Other Git hosting services are available, such as GitLab and Bitbucket.

Putting our projects on GitHub helps protect them against deletion, and also makes it easy to collaborate and share them. Our collaborators can access the project, download their own copy, and even contribute work back to us.

Let’s push our local repository to GitHub and share it publicly.

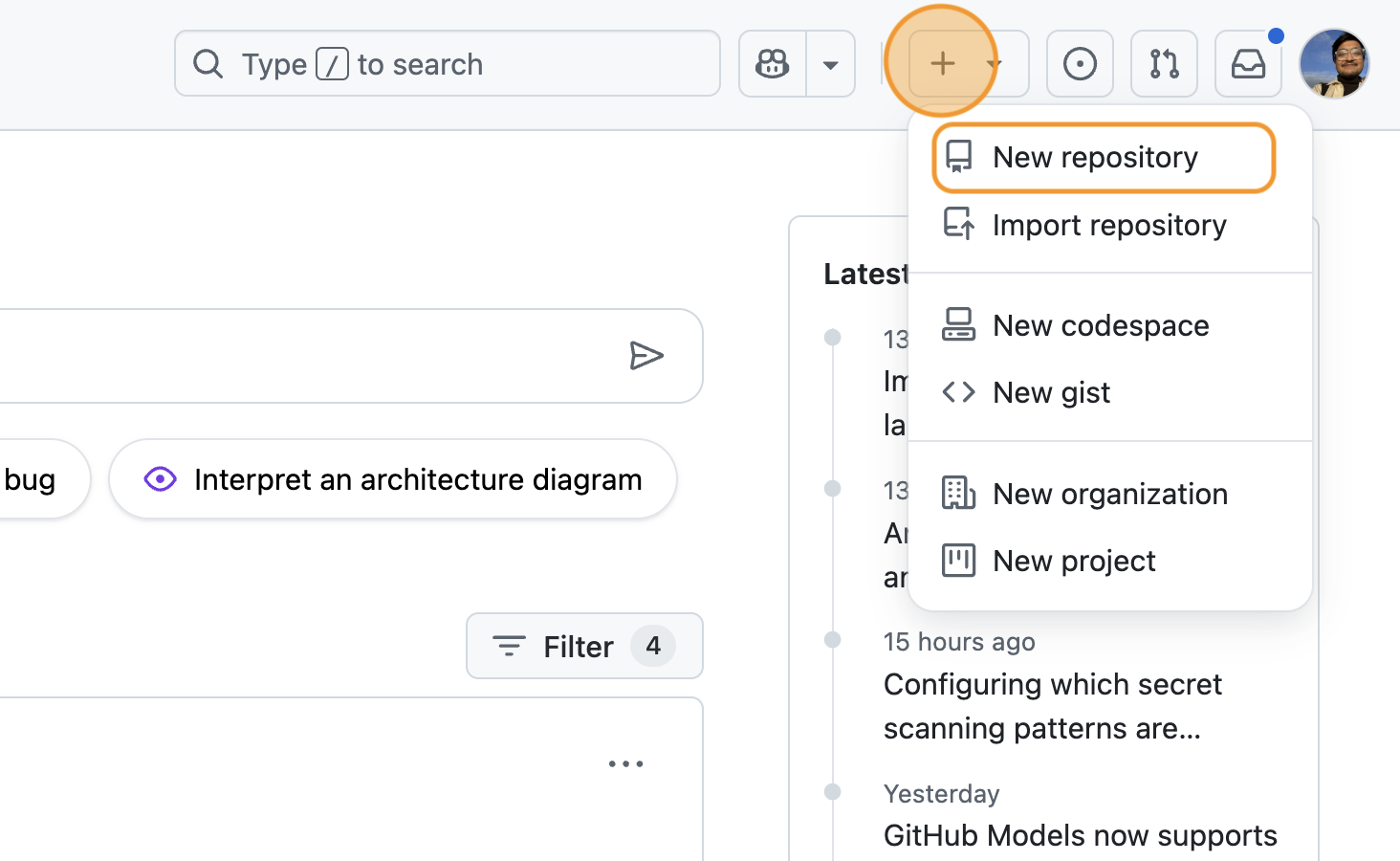

In your browser, navigate to https://github.com and sign into your account.

-

In the top right hand corner of the screen, there is a menu labelled “+” with a dropdown. Click the dropdown and select “New repository” from the options:

Creating a new GitHub repository

Creating a new GitHub repository -

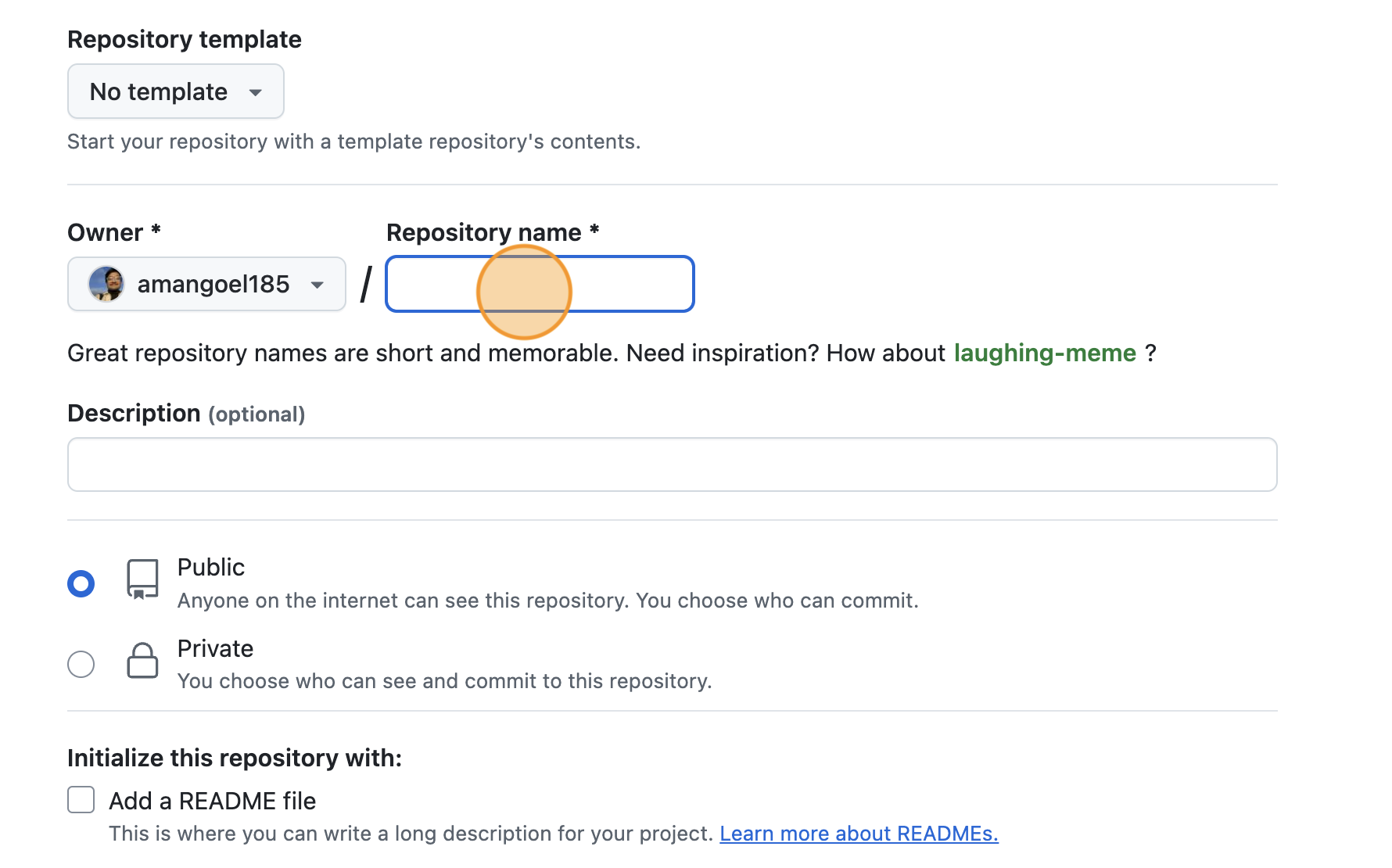

You will be presented with some options to fill in or select while creating your repository. In the “Repository Name” field, type “spacewalks”. This is the name of your project and matches the name of your local folder.

Naming the GitHub repository

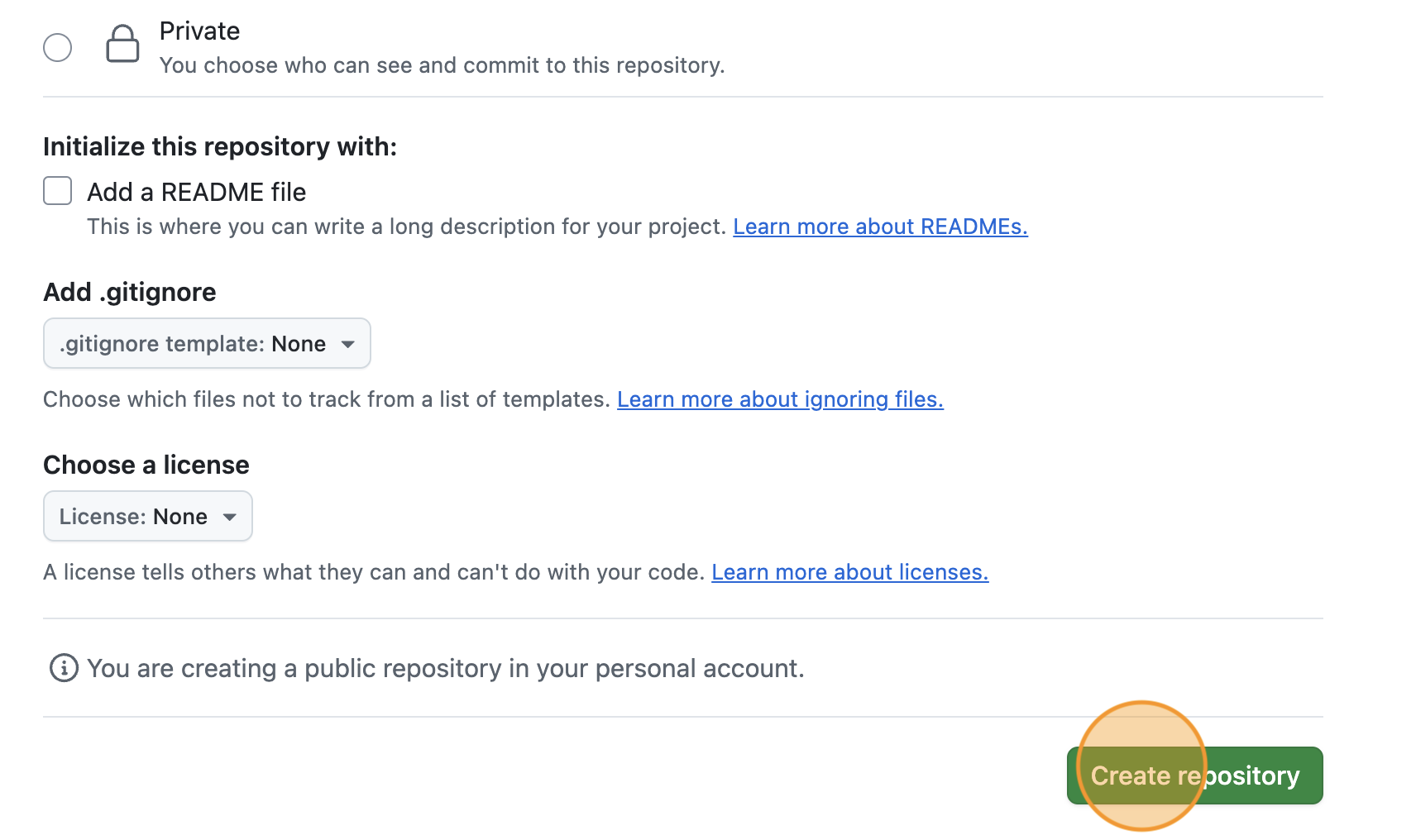

Naming the GitHub repositoryEnsure the visibility of the repository is “Public” and leave all other options blank. Since this repository will be connected to a local repository, it needs to be empty which is why we chose not to initialise with a README or add a license or

.gitignorefile. Click “Create repository” at the bottom of the page: Complete GitHub repository creation

Complete GitHub repository creation -

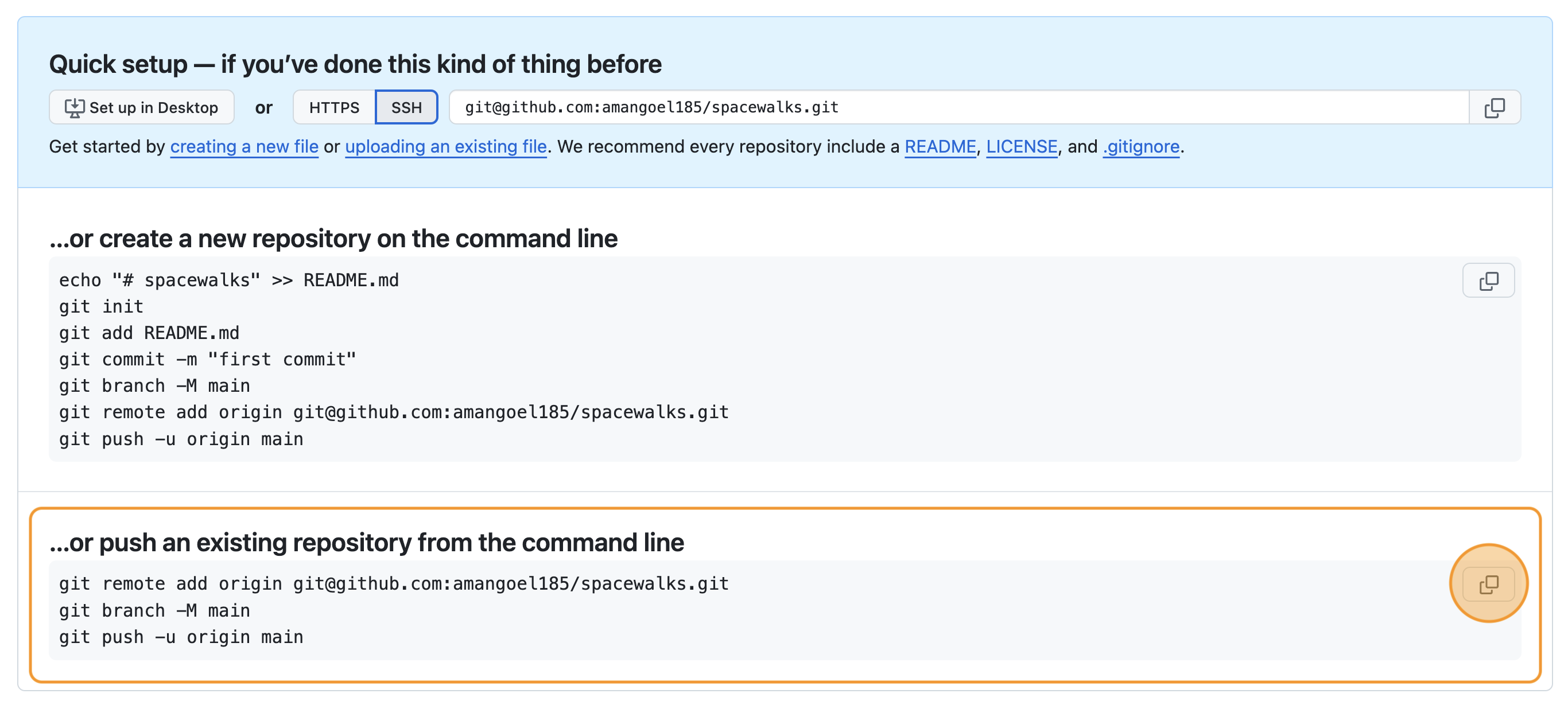

Now we have a remote repository on GitHub’s servers, you need to send it the files and history from your local repository. GitHub provides some instructions on how to do that for different scenarios. Change the toggle on the right side from “HTTPS” to “SSH”, then look at the heading “…or push an existing repository from the command line”. You should see instructions that look like this:

BASH

git remote add origin git@github.com/<YOUR_GITHUB_HANDLE>/spacewalks.git git branch -M main git push -u origin mainIt is very important you make sure you switch from “HTTPS” to “SSH”. In the setup, we configured our GitHub account and our local machine for SSH. If you select HTTPS, you will not be able to upload your files.

You can copy these commands using the button that looks like two overlapping squares to the right-hand side of the commands. Paste them into your terminal and run them.

- If you refresh your browser window, you should now see the two files

eva_data_analysis.pyandeva-data.jsonvisible in the GitHub repository, matching what you have locally on your machine.

If you were wondering about what those commands did, here is the explanation.

This command tells Git to create a remote called

“origin” and link it to the URL of your GitHub repository. A

remote is a version control concept where two (or more)

repositories are connected to each other, in such a way that they can be

kept in sync by exchanging commits. “origin” is a name used to refer to

the remote repository. It could be called anything, but “origin” is a

common convention for Git since it shows which is considered the “source

of truth”. This is particularly useful when many people are

collaborating on the same repository.

git branch is a command used to manage branches. We’ll

discuss branches later on in the course. We saw this command during

setup and earlier in this episode - it ensures the branch we are working

on is called “main”. This will be the default branch of the project for

everyone working on it.

The git push command is used to update a remote

repository with changes from your local repository. This command tells

Git to update the “main” branch on the “origin” remote. The

-u flag (short for --set-upstream) sets the

‘tracking reference’ for the current branch, so that in future

git push will default to sending to

origin main.

Software project in GitHub

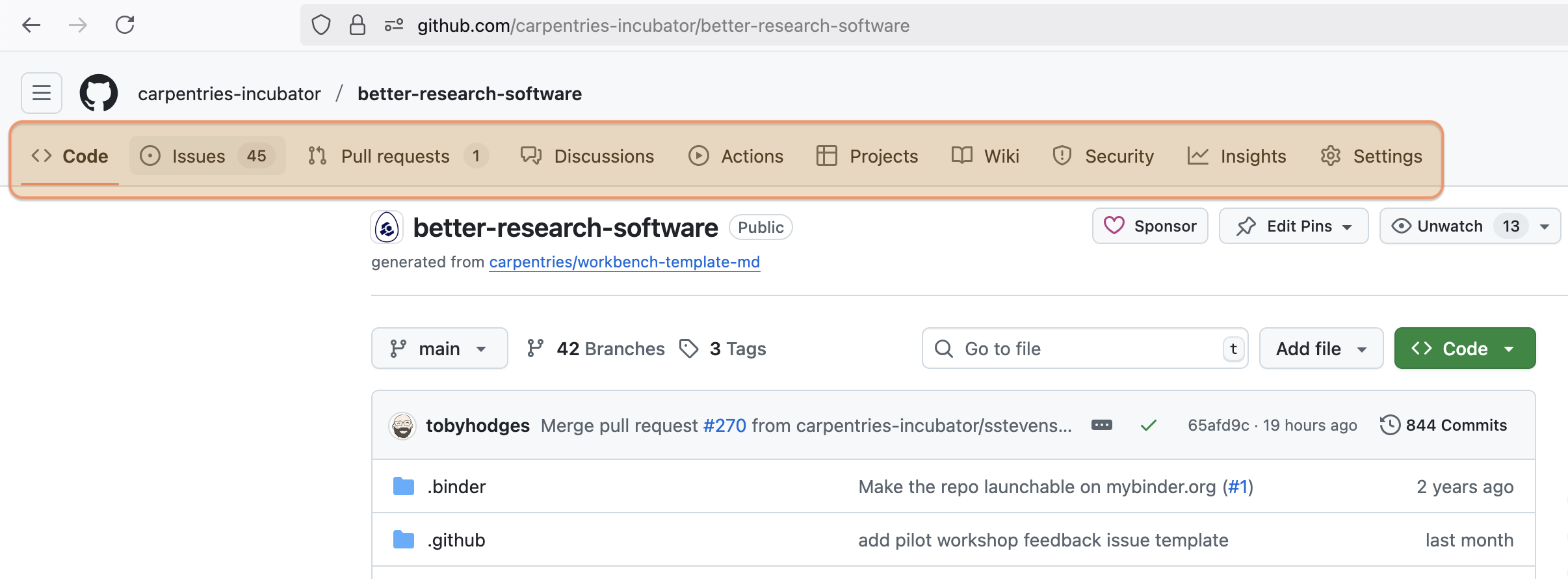

We now have our software project in GitHub and have linked it to our local working copy. We are ready to start more work on software development and publishing and backing up that work on GitHub. Let’s briefly explore the GitHub interface to our project.

In a GitHub software project, the tabs you see at the top of a repository page help organise different aspects of the project. Here’s a brief explanation of them:

- Code - shows the source code, folders, and files in the repository. This is where the main development work is done.

- Issues - used to track bugs, tasks, feature requests, or any work that needs to be done.

- Pull requests - where contributors submit changes to the code. These are reviewed and discussed before being merged.

- Actions - automated workflows (like tests or deployments) that run on the project using GitHub Actions.

- Projects - offers a Kanban-style board to manage tasks and plan work (e.g., using cards and columns).

- Wiki – lets you create structured documentation for your project.

- Security – helps identify, manage, and fix vulnerabilities in your code and dependencies.

- Insights – provides analytics on project activity, contributions, and community health.

- Settings - where you configure how the repository behaves and how others can interact with it.

These tabs help manage collaboration, development, and maintenance of the project. We will cover some of them in more detail as part of this course. You may not see all of these tabs depending on your access level to the repository and the configuration settings.

Keeping track of issues and planned work in GitHub

The one tab that we want to start using early on is Issues. This is where you report issues and bugs, track tasks, feature requests and what needs to be done and what problems exist, and capture general discussions related to the project.

Each issue acts like a conversation thread, where contributors can describe a problem or idea, discuss it, attach code snippets or images, and reference commits or pull requests or mention other team members. It allows contributors to discuss and refine ideas before making changes, and helps prioritise work and organise releases. The Issues tab serves as the project’s task board and communication hub, making development more organised, transparent and inclusive.

It is important to start listing things that need doing on the project early on so you do not forget about them. The Issues tab is a good place to create that list and keep it together with the code.

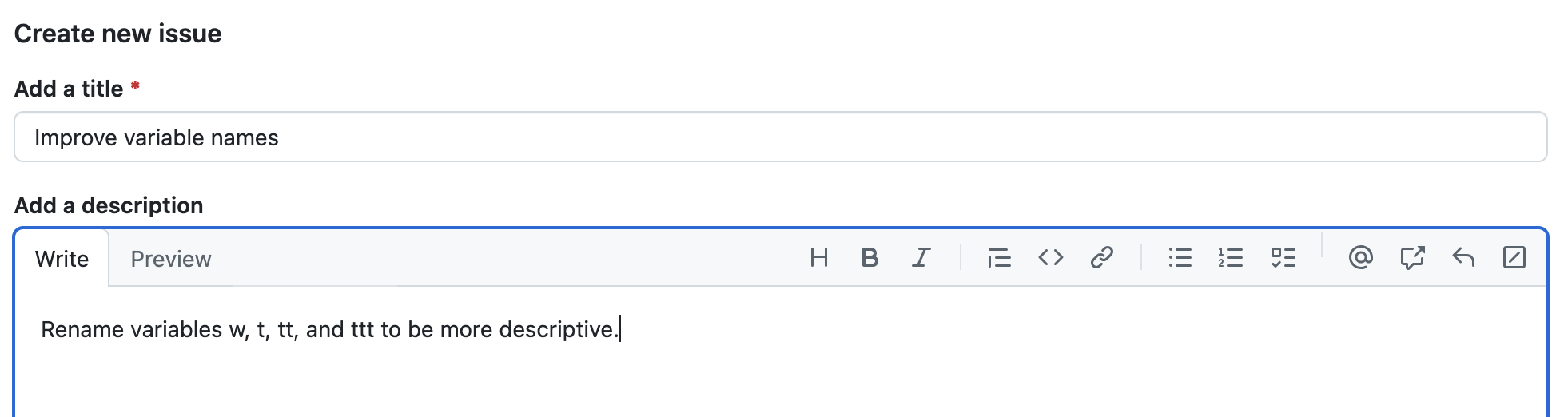

In one of the the previous exercises, we have identified a number of things that could be improved with our software. Let’s add one of them as an issue now (we will continue to do this throughout the course - this is good practice).

For example, we identified that variables (e.g. t,

tt, ttt) should have more descriptive and

meaningful names. To add this as an issue in GitHub, go to the

Issues tab in your project’s GitHub page, and click the

“New issue” green button. In the form that appears, we add a descriptive

title for this new issue (e.g. “improve variable names”) and write more

details about the issue (e.g. “rename variables t,

tt, and ttt to be more descriptive”).

Later on in the course, we will learn how to comment, reference, add more details and close issues.

Summary

We have created a new software project and used version control system Git to track changes to it. We can now look back at our work, compare different code versions, and even recover past states. We have also published our software to a remote repository located on GitHub, where it is both secure and shareable.

These skills are critical to reproducible and sustainable science. Software is science, and being able to share the specific version of code used in a paper is required for reproducibility. But we, as researchers, also benefit from having a clear, self-documented record of what we did, when and why. It makes it much easier to track down and fix our bugs, return to work on projects we took a break from, and even for other people to pick up our work.

Before we start making changes to the code, we have to set up a development environment with software dependencies for our project to ensure this metadata about our project is recorded and shared with anyone wishing to download, run or extend our software (and this includes ourselves on a different machine or operating system).

At this point, the code in your local software project’s directory should be as in: https://github.com/carpentries-incubator/bbrs-software-project/tree/03-reproducible-dev-environment

Further reading

We recommend the following resources for some additional reading on the topic of this episode:

- Software Carpentry’s Git Novice lesson

- The Turing Way’s “Guide to Version Control”

- “How Git Works” course on Pluralsight

- How to Write a Good Commit Message

- Git Commit Good Practice

Also check the full reference set for the course.

- Version control systems are software that tracks and manages changes to a project over time

- Using version control aids reproducibility since the exact state of the software that produced an output can be recovered

- A commit represents the smallest unit of change to a project

- Commit messages describe what each commit contains and should be descriptive

- GitHub is a hosting service for sharing and collaborating on software

- Using version control is one of the first steps to creating a software project from a bunch of scripts - by investing in these practices early, researchers can create software that supports their work more effectively and enables others to build upon it with confidence.