Introduction

Last updated on 2025-12-01 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is Natural Language Processing?

- What are some common applications of NLP?

- What makes text different from other data?

- Why not just learn Large Language Models?

- What linguistic properties should we consider when dealing with texts?

Objectives

- Define Natural Language Processing

- Show the most relevant NLP tasks and applications in practice

- Learn how to handle Linguistic Data and how is Linguistics relevant to NLP

What is NLP?

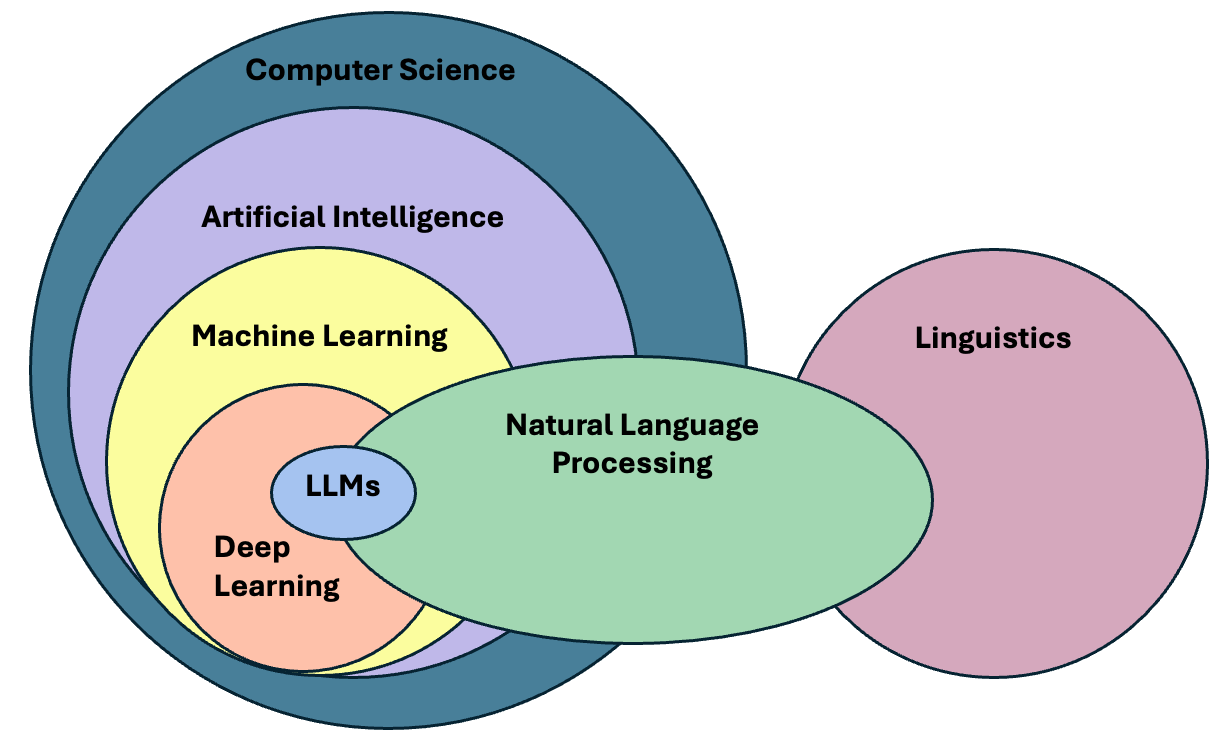

Natural language processing (NLP) is an area of research and application that focuses on making human languages processable for computers, so that they can perform useful tasks. It is therefore not a single method, but a collection of techniques that help us deal with linguistic inputs. The range of techniques spans simple word counts, to Machine Learning (ML) methods, all the way up to complex Deep Learning (DL) architectures.

We use the term “natural language”, as opposed to “artificial language” such as programming languages, which are by design constructed to be easily formalized into machine-readable instructions. In contrast to programming languages, natural languages are complex, ambiguous, and heavily context-dependent, making them challenging for computers to process. To complicate matters, there is not only a single human language. More than 7000 languages are spoken around the world, each with its own grammar, vocabulary, and cultural context.

In this course we will mainly focus on written language, specifically written English, we leave out audio and speech, as they require a different kind of input processing. But consider that we use English only as a convenience so we can address the technical aspects of processing textual data. While ideally most of the concepts from NLP apply to most languages, one should always be aware that certain languages require different approaches to solve seemingly similar problems. We would like to encourage the usage of NLP in other less widely known languages, especially if it is a minority language. You can read more about this topic in this blogpost.

NLP in the real world

Name three to five tools/products that you use on a daily basis and that you think leverage NLP techniques. To do this exercise you may make use of the Web.

These are some of the most popular NLP-based products that we use on a daily basis:

- Agentic Chatbots (ChatGPT, Perplexity)

- Voice-based assistants (e.g., Alexa, Siri, Cortana)

- Machine translation (e.g., Google translate, DeepL, Amazon translate)

- Search engines (e.g., Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo)

- Keyboard autocompletion on smartphones

- Spam filtering

- Spell and grammar checking apps

- Customer care chatbots

- Text summarization tools (e.g., news aggregators)

- Sentiment analysis tools (e.g., social media monitoring)

We can already find differences between languages in the most basic step for processing text. Take the problem of segmenting text into meaningful units, most of the times these units are words, in NLP we call this task tokenization. A naive approach is to obtain individual words by splitting text by spaces, as it seems obvious that we always separate words with spaces. Just as human beings break up sentences into words, phrases and other units in order to learn about grammar and other structures of a language, NLP techniques achieve a similar goal through tokenization. Let’s see how can we segment or tokenize a sentence in English:

PYTHON

english_sentence = "Tokenization isn't always trivial."

english_words = english_sentence.split(" ")

print(english_words)

print(len(english_words))OUTPUT

['Tokenization', "isn't", 'always', 'trivial.']

4The words are mostly well separated, however we do not get fully formed words (we have punctuation with the period after “trivial” and also special cases such as the abbreviation of “is not” into “isn’t”). But at least we get a rough count of the number of words present in the sentence. Let’s now look at the same example in Chinese:

PYTHON

# Chinese Translation of "Tokenization is not always trivial"

chinese_sentence = "标记化并不总是那么简单"

chinese_words = chinese_sentence.split(" ")

print(chinese_words)

print(len(chinese_words))OUTPUT

['标记化并不总是那么简单']

1The same example however did not work in Chinese, because Chinese does not use spaces to separate words. This is an example of how the idiosyncrasies of human language affects how we can process them with computers. We therefore need to use a tokenizer specifically designed for Chinese to obtain the list of well-formed words in the text. Here we use a “pre-trained” tokenizer called MicroTokenizer, which uses a dictionary-based approach to correctly identify the distinct words:

PYTHON

import MicroTokenizer # A popular Chinese text segmentation library

chinese_sentence = "标记化并不总是那么简单"

chinese_words = MicroTokenizer.cut(chinese_sentence)

print(chinese_words)

# ['mark', 'transform', 'and', 'no', 'always', 'so', 'simple']

print(len(chinese_words)) # Output: 7OUTPUT

['标记', '化', '并', '不', '总是', '那么', '简单']

7We can trust that the output is valid because we are using a verified

library - MicroTokenizer, even though we don’t speak

Chinese. Another interesting aspect is that the Chinese sentence has

more words than the English one, even though they convey the same

meaning. This shows the complexity of dealing with more than one

language at a time, as is the case in task such as Machine

Translation (using computers to translate speech or text from

one human language to another).

Natural Language Processing deals with the challenges of correctly processing and generating text in any language. This can be as simple as counting word frequencies to detect different writing styles, using statistical methods to classify texts into different categories, or using deep neural networks to generate human-like text by exploiting word co-occurrences in large amounts of texts.

Why should we learn NLP Fundamentals?

In the past decade, NLP has evolved significantly, especially in the field of deep learning, to the point that it has become embedded in our daily lives, one just needs to look at the term Large Language Models (LLMs), the latest generation of NLP models, which is now ubiquitous in news media and tech products we use on a daily basis.

The term LLM now is often (and wrongly) used as a synonym of Artificial Intelligence. We could therefore think that today we just need to learn how to manipulate LLMs in order to fulfill our research goals involving textual data. The truth is that Language Modeling has always been part of the core tasks of NLP, therefore, by learning NLP you will understand better where are the main ideas behind LLMs coming from.

LLM is a blanket term for an assembly of large neural networks that are trained on vast amounts of text data with the objective of optimizing for language modeling. Once they are trained, they are used to generate human-like text or fine-tunned to perform much more advanced tasks. Indeed, the surprising and fascinating properties that emerge from training models at this scale allows us to solve different complex tasks such as answer elaborate questions, translate languages, solve complex problems, generate narratives that emulate reasoning, and many more, all of this with a single tool.

It is important, however, to pay attention to what is happening behind the scenes in order to be able trace sources of errors and biases that get hidden in the complexity of these models. The purpose of this course is precisely to take a step back, and understand that:

- There are a wide variety of tools available, beyond LLMs, that do not require so much computing power

- Sometimes a much simpler method than an LLM is available that can solve our problem at hand

- If we learn how previous approaches to solve linguistic problems were designed, we can better understand the limitations of LLMs and how to use them effectively

- LLMs excel at confidently delivering information, without any regards for correctness. This calls for a careful design of evaluation metrics that give us a better understanding of the quality of the generated content.

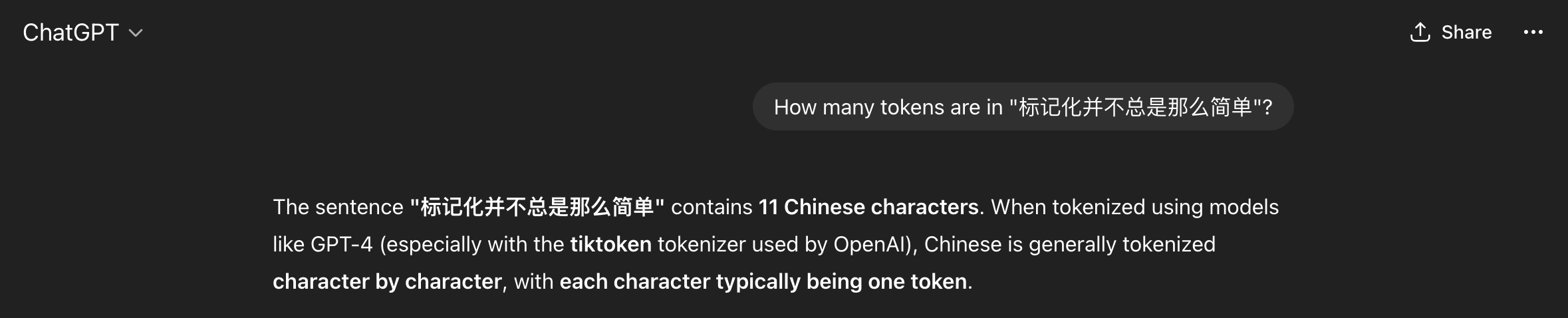

Let’s go back to our problem of segmenting text and see what ChatGPT has to say about tokenizing Chinese text:

We got what sounds like a straightforward confident answer. However, it is not clear how the model arrived at this solution. Second, we do not know whether the solution is correct or not. In this case ChatGPT made some assumptions for us, such as choosing a specific kind of tokenizer to give the answer, and since we do not speak the language, we do not know if this is indeed the best approach to tokenize Chinese text. If we understand the concept of Token (which we will today!), then we can be more informed about the quality of the answer, whether it is useful to us, and therefore make a better use of the model.

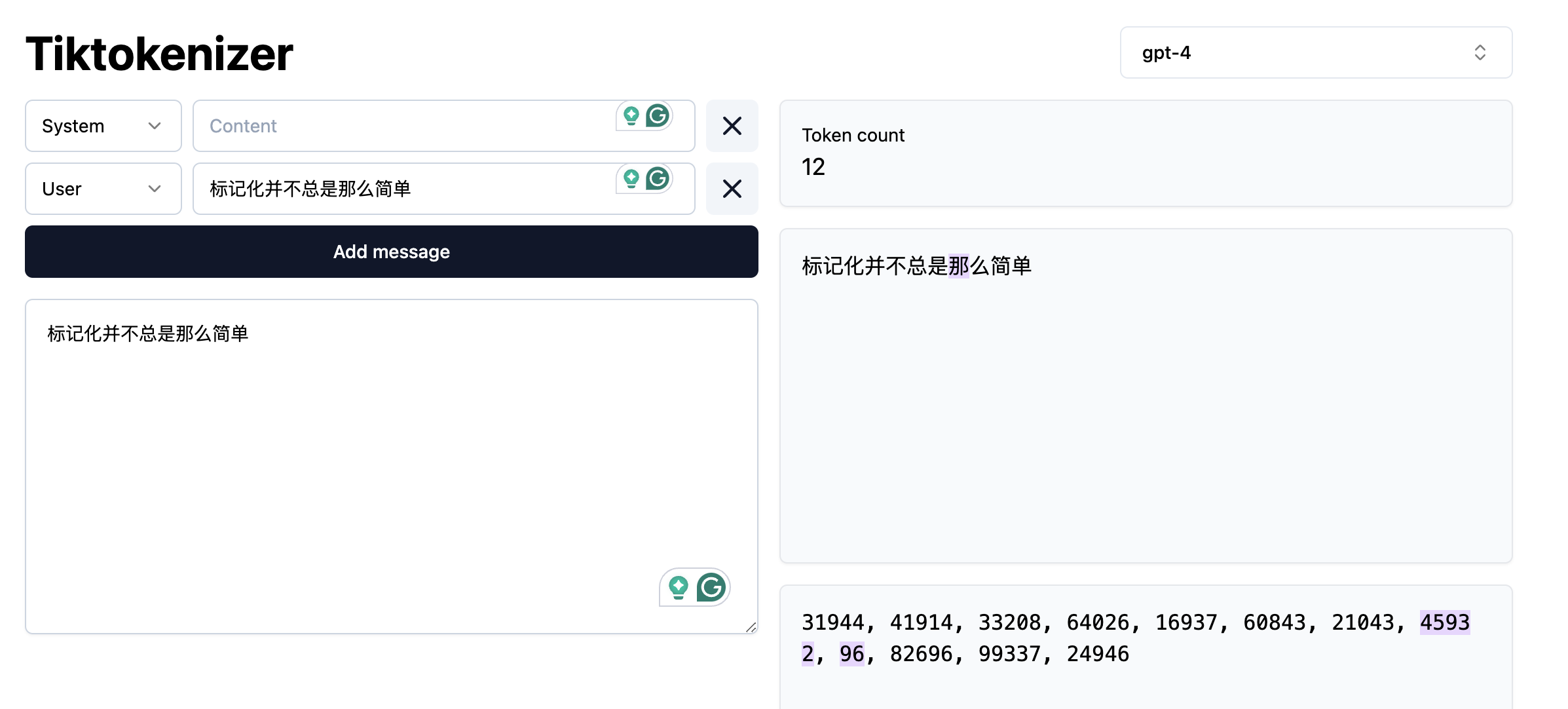

And by the way, ChatGPT was almost correct, in the specific case of the gpt-4 tokenizer, the model will return 12 tokens (not 11!) for the given Chinese sentence.

We can also argue if the statement “Chinese is generally tokenized character by character” is an overstatement or not. In any case, the real question here is: Are we ok with almost correct answers? Please note that this is not a call to avoid using LLM’s but a call for a careful consideration of usage and more importantly, an attempt to explain the mechanisms behind via NLP concepts.

Language as Data

From a more technical perspective, NLP focuses on applying advanced statistical techniques to linguistic data. This is a key factor, since we need a structured dataset with a well defined set of features in order to manipulate it numerically. Your first task as an NLP practitioner is to understand what aspects of textual data are relevant for your application and apply techniques to systematically extract meaningful features from unstructured data (if using statistics or Machine Learning) or choose an appropriate neural architecture (if using Deep Learning) that can help solve our problem at hand.

What is a word?

When dealing with language our basic data unit is usually a word. We deal with sequences of words and with how they relate to each other to generate meaning in text pieces. Thus, our first step will be to load a text file and provide it with structure by splitting it into valid words (tokenization)!

Token vs Word

For simplicity, in the rest of the course we will use the terms “word” and “token” interchangeably, but as we just saw they do not always have the same granularity. Originally the concept of token comprised dictionary words, numeric symbols and punctuation. Nowadays, tokenization has also evolved and became an optimization task on its own (How can we segment text in a way that neural networks learn optimally from text?). Tokenizers allow one to reconstruct or revert back to the original pre-tokenized form of tokens or words, hence we can afford to use token and word as synonyms. If you are curious, you can visualize how different state-of-the-art tokenizers split text in this WebApp

Let’s open a file, read it into a string and split it by spaces. We will print the original text and the list of “words” to see how they look:

PYTHON

with open("data/84_frankenstein_clean.txt") as f:

text = f.read()

print(text[:100])

print("Length:", len(text))

proto_tokens = text.split()

print(proto_tokens[:40])

print(len(proto_tokens))OUTPUT

Letter 1 St. Petersburgh, Dec. 11th, 17-- TO Mrs. Saville, England You will rejoice to hear that no disaster has accompanied the commencement of an en

Length: 417931

Proto-Tokens:

['Letter', '1', 'St.', 'Petersburgh,', 'Dec.', '11th,', '17--', 'TO', 'Mrs.', 'Saville,', 'England', 'You', 'will', 'rejoice', 'to', 'hear', 'that', 'no', 'disaster', 'has', 'accompanied', 'the', 'commencement', 'of', 'an', 'enterprise', 'which', 'you', 'have', 'regarded', 'with', 'such', 'evil', 'forebodings.', 'I', 'arrived', 'here', 'yesterday,', 'and', 'my']

74942Splitting by white space is possible but needs several extra steps to separate out punctuation appropriately. A more sophisticated approach is to use the spaCy library to segment the text into human-readable tokens. First we will download the pre-trained model, in this case we only need the small English version:

This is a model that spaCy already trained for us on a subset of web English data. Hence, the model already “knows” how to tokenize into English words. When the model processes a string, it does not only do the splitting for us but already provides more advanced linguistic properties of the tokens (such as part-of-speech tags, or named entities). You can check more languages and models in the spacy documentation

Pre-trained Models and Fine-tuning

These two terms frequently arise in discussions of NLP. The notion of pre-trained comes from Machine Learning and describes a model that has already been optimized on relevant data for a given task. Such a model can typically be loaded and applied directly to new datasets, often working “out of the box.” without need of further refinement. Ideally, publicly released pre-trained models have undergone rigorous testing for both generalization and output quality on different textual data that it was intended to be used on. Nevertheless, it remains essential to carefully review the evaluation methods used before relying on them in practice. It is also recommended that you perform your own evaluation of the model on text that you intend to use it on.

Sometimes a pre-trained model is of good quality, but it does not fit the nuances of our specific dataset. For example, the model was trained on newspaper articles but you are interested in poetry. In this case, it is common to perform fine-tuning, this means that instead of training your own model from scratch, you start with the knowledge obtained in the pre-trained model and adjust it (fine-tune it) to work optimally with your specific data. If this is done well it leads to increased performance in the specific task you are trying to solve. The advantage of fine-tuning is that you often do not need a large amount of data to improve the results, hence the popularity of the technique.

Let’s now import the model and use it to parse our document:

PYTHON

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm") # we load the small English model for efficiency

doc = nlp(text) # Doc is a python object with several methods to retrieve linguistic properties

# SpaCy-Tokens

tokens = [token.text for token in doc] # Note that spacy tokens are also python objects

print(tokens[:40])

print(len(tokens))OUTPUT

['Letter', '1', 'St.', 'Petersburgh', ',', 'Dec.', '11th', ',', '17', '-', '-', 'TO', 'Mrs.', 'Saville', ',', 'England', 'You', 'will', 'rejoice', 'to', 'hear', 'that', 'no', 'disaster', 'has', 'accompanied', 'the', 'commencement', 'of', 'an', 'enterprise', 'which', 'you', 'have', 'regarded', 'with', 'such', 'evil', 'forebodings', '.']

85713The differences look subtle at the beginning, but if we carefully inspect the way spaCy splits the text, we can see the advantage of using a specialized tokenizer. There are also several useful features that spaCy provides us with. For example, we can choose to extract only symbols, or only alphanumerical tokens, and more advanced linguistic properties, for example we can remove punctuation and only keep alphanumerical tokens:

PYTHON

only_words = [token for token in doc if token.is_alpha] # Only alphanumerical tokens

print(only_words[:50])

print(len(only_words))OUTPUT

[Letter, Petersburgh, TO, Saville, England, You, will, rejoice, to, hear, that, no, disaster, has, accompanied, the, commencement, of, an, enterprise, which, you, have, regarded, with, such, evil, forebodings, I, arrived, here, yesterday, and, my, first, task, is, to, assure, my, dear, sister, of, my, welfare, and, increasing, confidence, in, the]

75062or keep only the verbs from our text:

PYTHON

only_verbs = [token for token in doc if token.pos_ == "VERB"] # Only verbs

print(only_verbs[:10])

print(len(only_verbs))OUTPUT

[rejoice, hear, accompanied, regarded, arrived, assure, increasing, walk, feel, braces]

10148SpaCy also predicts the sentences under the hood for us. It might seem trivial to you as a human reader to recognize where a sentence begins and ends but for a machine, just like finding words, finding sentences is a task on its own, for which sentence-segmentation models exist. In the case of Spacy, we can access the sentences like this:

PYTHON

sentences = [sent.text for sent in doc.sents] # Sentences are also python objects

print(sentences[:5])

print(len(sentences))OUTPUT

['Letter 1 St. Petersburgh, Dec. 11th, 17-- TO Mrs. Saville, England You will rejoice to hear that no disaster has accompanied the commencement of an enterprise which you have regarded with such evil forebodings.', 'I arrived here yesterday, and my first task is to assure my dear sister of my welfare and increasing confidence in the success of my undertaking.', 'I am already far north of London, and as I walk in the streets of Petersburgh, I feel a cold northern breeze play upon my cheeks, which braces my nerves and fills me with delight.', 'Do you understand this feeling?', 'This breeze, which has traveled from the regions towards which I am advancing, gives me a foretaste of those icy climes.']

3317We can also see what named entities the model predicted:

OUTPUT

1713

DATE Dec. 11th

CARDINAL 17

PERSON Saville

GPE England

DATE yesterdayThese are just basic tests to demonstrate how you can immediately process the structure of text using existing NLP libraries. The spaCy models we used are simpler relative to state of the art approaches. So the more complex the input text and task, the more errors are likely to appear when using such models. The biggest advantage of using these existing libraries is that they help you transform unstructured plain text files into structured data that you can manipulate later for your own goals such as training language models.

Computing stats with spaCy

Use the spaCy Doc object to compute an aggregate statistic about the

Frankenstein book. HINT: Use the python set,

dictionary or Counter objects to hold the

accumulative counts. For example:

- Give the list of the 20 most common verbs in the book

- How many different Places are identified in the book? (Label = GPE)

- How many different entity categories are in the book?

- Who are the 10 most mentioned PERSONs in the book?

- Or any other similar aggregate you want…

Let’s describe the solution to obtain all the different entity categories. For that we should iterate the whole text and keep a python set with all the seen labels.

PYTHON

entity_types = set()

for ent in doc.ents:

entity_types.add(ent.label_)

print(entity_types)

print(len(entity_types))OUTPUT

{'CARDINAL', 'GPE', 'WORK_OF_ART', 'ORDINAL', 'DATE', 'LAW', 'PRODUCT', 'QUANTITY', 'ORG', 'TIME', 'PERSON', 'LOC', 'LANGUAGE', 'FAC', 'NORP'}

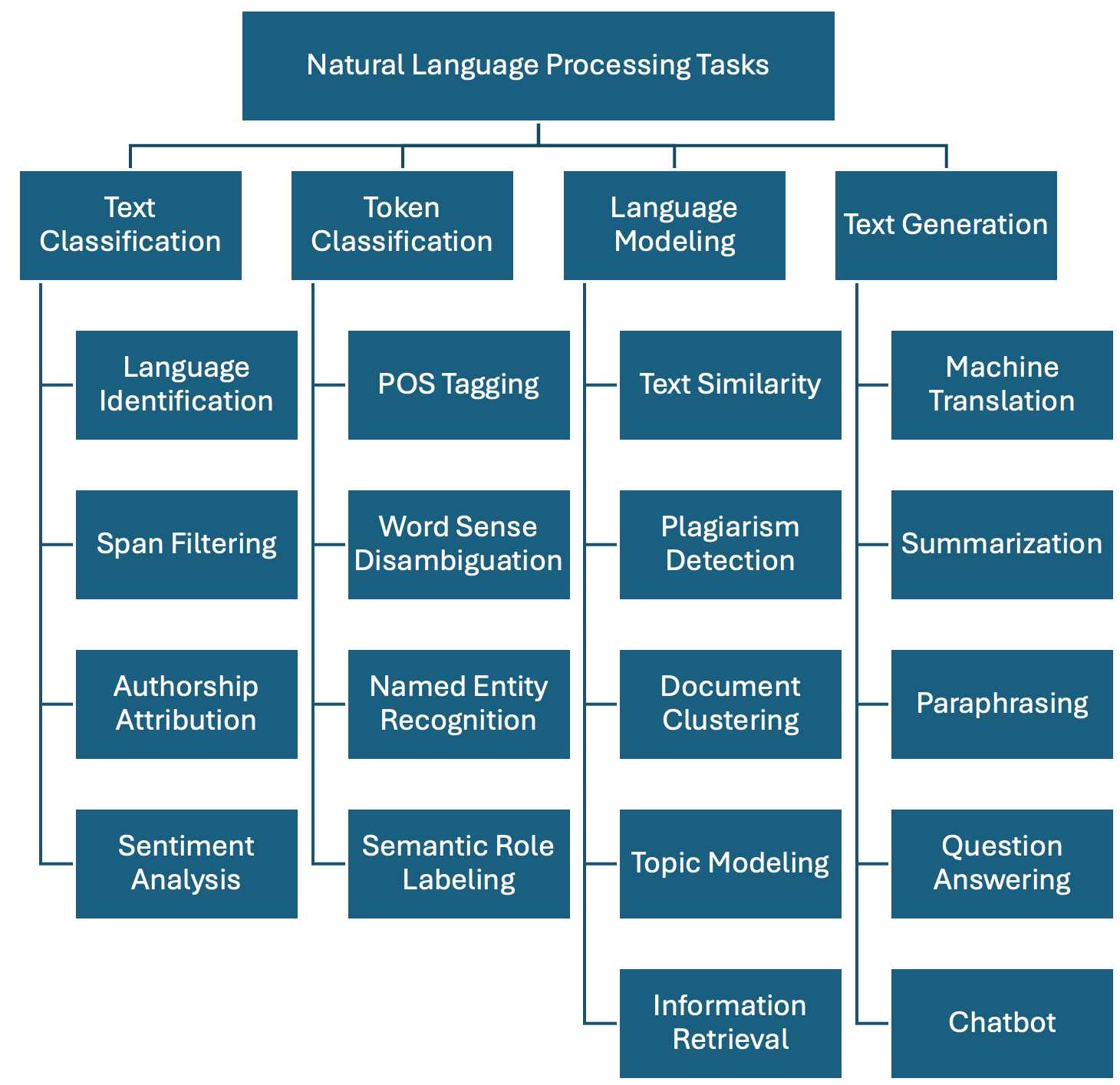

15NLP tasks

The previous exercise shows that a great deal of NLP techniques are embedded in our daily life. Indeed NLP is an important component in a wide range of software applications that we use in our day to day activities.

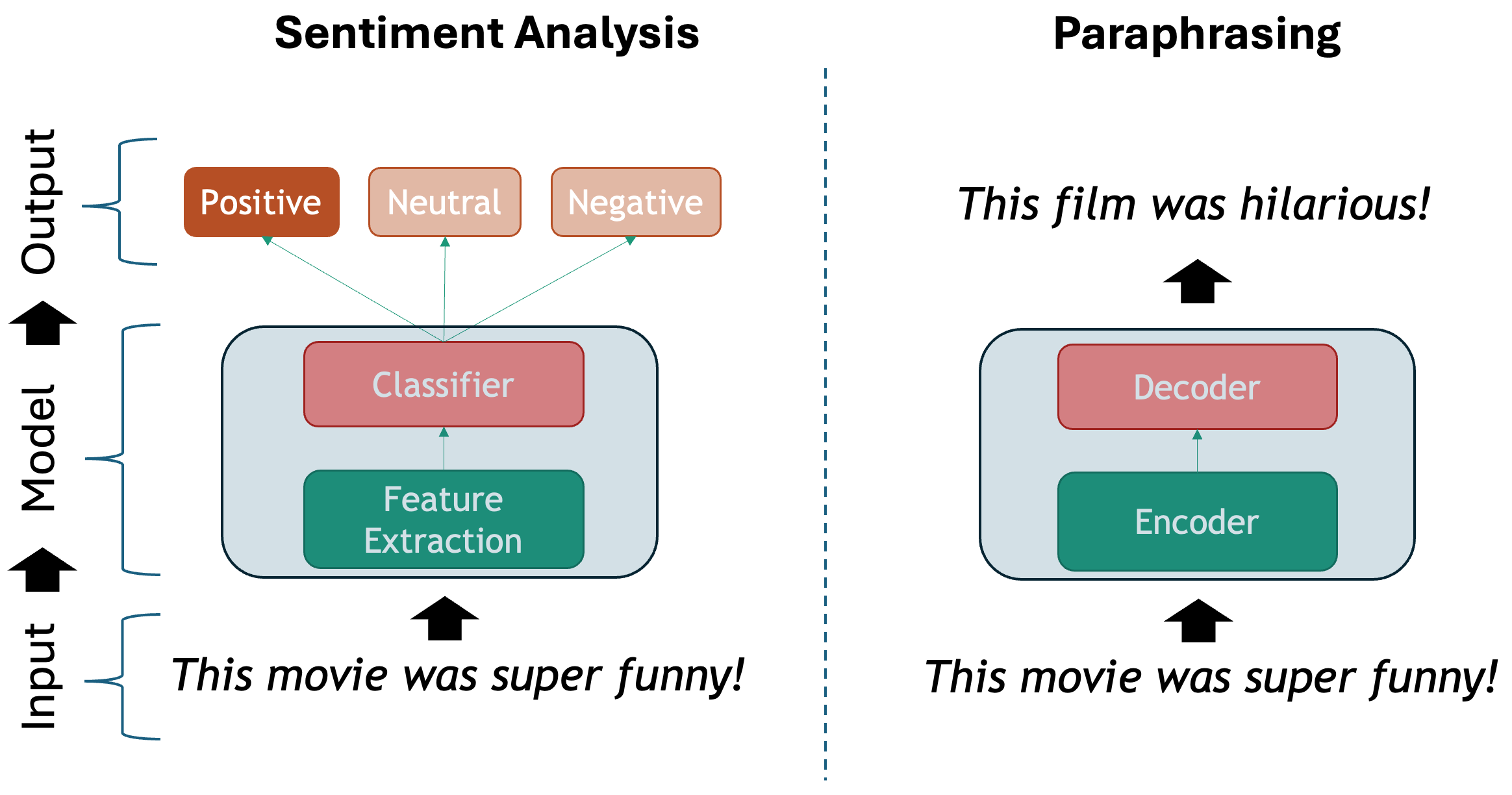

There are several ways to describe the tasks that NLP solves. From the Machine Learning perspective, we have:

- Unsupervised tasks: exploiting existing patterns from large amounts of text.

- Supervised tasks: learning to classify texts given a labeled set of examples

The Deep Learning perspective usually involves the selection of the right model among different neural network architectures to tackle an NLP task, such as:

Multi-layer Perceptron

Recurrent Neural Network

Convolutional Neural Network

Long-Short Term Memory Networks (LSTMs)

Transformer (including LLMs!)

Regardless of the chosen method, below we show one possible taxonomy of NLP tasks. The tasks are grouped together with some of their most prominent applications. This is definitely a non-exhaustive list, as in reality there are hundreds of them, but it is a good start:

-

Text Classification: Assign one or more labels to a given piece of text. This text is usually referred to as a document and in our context this can be a sentence, a paragraph, a book chapter, etc…

- Language Identification: determining the language in which a particular input text is written.

- Spam Filtering: classifying emails into spam or not spam based on their content.

- Authorship Attribution: determining the author of a text based on its style and content (based on the assumption that each author has a unique writing style).

- Sentiment Analysis: classifying text into positive, negative or neutral sentiment. For example, in the sentence “I love this product!”, the model would classify it as positive sentiment.

-

Token Classification: The task of individually assigning one label to each word in a document. This is a one-to-one mapping; however, because words do not occur in isolation and their meaning depend on the sequence of words to the left or the right of them, this is also called Word-In-Context Classification or Sequence Labeling and usually involves syntactic and semantic analysis.

- Part-Of-Speech Tagging: is the task of assigning a part-of-speech label (e.g., noun, verb, adjective) to each word in a sentence.

- Chunking: splitting a running text into “chunks” of words that together represent a meaningful unit: phrases, sentences, paragraphs, etc.

- Word Sense Disambiguation: based on the context what does a word mean (think of “book” in “I read a book.” vs “I want to book a flight.”)

- Named Entity Recognition: recognize world entities in text, e.g. Persons, Locations, Book Titles, or many others. For example “Mary Shelley” is a person, “Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus” is a book, etc.

- Semantic Role Labeling: the task of finding out “Who did what to whom?” in a sentence: information from events such as agents, participants, circumstances, subject-verb-object triples etc.

- Relation Extraction: the task of identifying named relationships between entities in a text, e.g. “Apple is based in California” has the relation (Apple, based_in, California).

- Co-reference Resolution: the task of determining which words refer to the same entity in a text, e.g. “Mary is a doctor. She works at the hospital.” Here “She” refers to “Mary”.

- Entity Linking: the task of disambiguation of named entities in a text, linking them to their corresponding entries in a knowledge base, e.g. Mary Shelley’s biography in Wikipedia.

-

Language Modeling: Given a sequence of words, the model predicts the next word. For example, in the sentence “The capital of France is _____”, the model should predict “Paris” based on the context. This task was initially useful for building solutions that require speech and optical character recognition (even handwriting), language translation and spelling correction. Nowadays this has scaled up to the LLMs that we know. A byproduct of pre-trained Language Modeling is the vectorized representation of texts which allows to perform specific tasks such as:

- Text Similarity: The task of determining how similar two pieces of text are.

- Plagiarism detection: determining whether a piece of text, B, is close enough to another known piece of text, A, which increases the likelihood that it was plagiarized.

- Document clustering: grouping similar texts together based on their content.

- Topic modelling: a specific instance of clustering, here we automatically identify abstract “topics” that occur in a set of documents, where each topic is represented as a cluster of words that frequently appear together.

- Information Retrieval: this is the task of finding relevant information or documents from a large collection of unstructured data based on user’s query, e.g., “What’s the best restaurant near me?”.

-

Text Generation: the task of generating text based on a given input. This is usually done by generating the output word by word, conditioned on both the input and the output so far. The difference with Language Modeling is that for generation there are higher-level generation objectives such as:

- Machine Translation: translating text from one language to another, e.g., “Hello” in English to “Que tal” in Spanish.

- Summarization: generating a concise summary of a longer text. It can be abstractive (generating new sentences that capture the main ideas of the original text) but also extractive (selecting important sentences from the original text).

- Paraphrasing: generating a new sentence that conveys the same meaning as the original sentence, e.g., “The cat is on the mat.” to “The mat has a cat on it.”.

- Question Answering: given a question and a context, the model generates an answer. For example, given the question “What is the capital of France?” and the Wikipedia article about France as the context, the model should answer “Paris”. This task can be approached as a text classification problem (where the answer is one of the predefined options) or as a generative task (where the model generates the answer from scratch).

- Conversational Agent (ChatBot): Building a system that interacts with a user via natural language, e.g., “What’s the weather today, Siri?”. These agents are widely used to improve user experience in customer service, personal assistance and many other domains.

For the purposes of this episode, we will focus on supervised learning tasks and we will emphasize how the Transformer architecture is used to tackle some of them.

Inputs and Outputs

Look at the NLP Task taxonomy described above and write down a couple of examples of (Input, Output) instance pairs that you would need in order to train a supervised model for your chosen task.

For Example: the task of labeling an E-mail as spam or not-spam

Label_Set: [SPAM, NO-SPAM]

Training Instances:

Input: “Dear Sir, you’ve been awarded a grant of 10 million Euros and it is only available today. Please contact me ASAP!” Output: SPAM

Input: “Dear Madam, as agreed by phone here is the sales report for last month.” Output: NO-SPAM

Example B: the task of Conversational agent. Here are 3 instances to provide supervision for a model:

Label_Set: Output vocabulary. This is: learning to generate token by token a coherent response that addresses the input question.

Input: “Hello, how are you?” Output: “I am fine thanks!”

Input: “Do you know at what time is the World Cup final today?” Output: “Yes, the World Cup final will be at 6pm CET”

Input: “What color is my shirt?” Output: “Sorry, I am unable to see what you are wearing.”

A Primer on Linguistics

Natural language exhibits a set of properties that make it more challenging to process than other types of data such as tables, spreadsheets or time series. Language is hard to process because it is compositional, ambiguous, discrete and sparse.

Compositionality

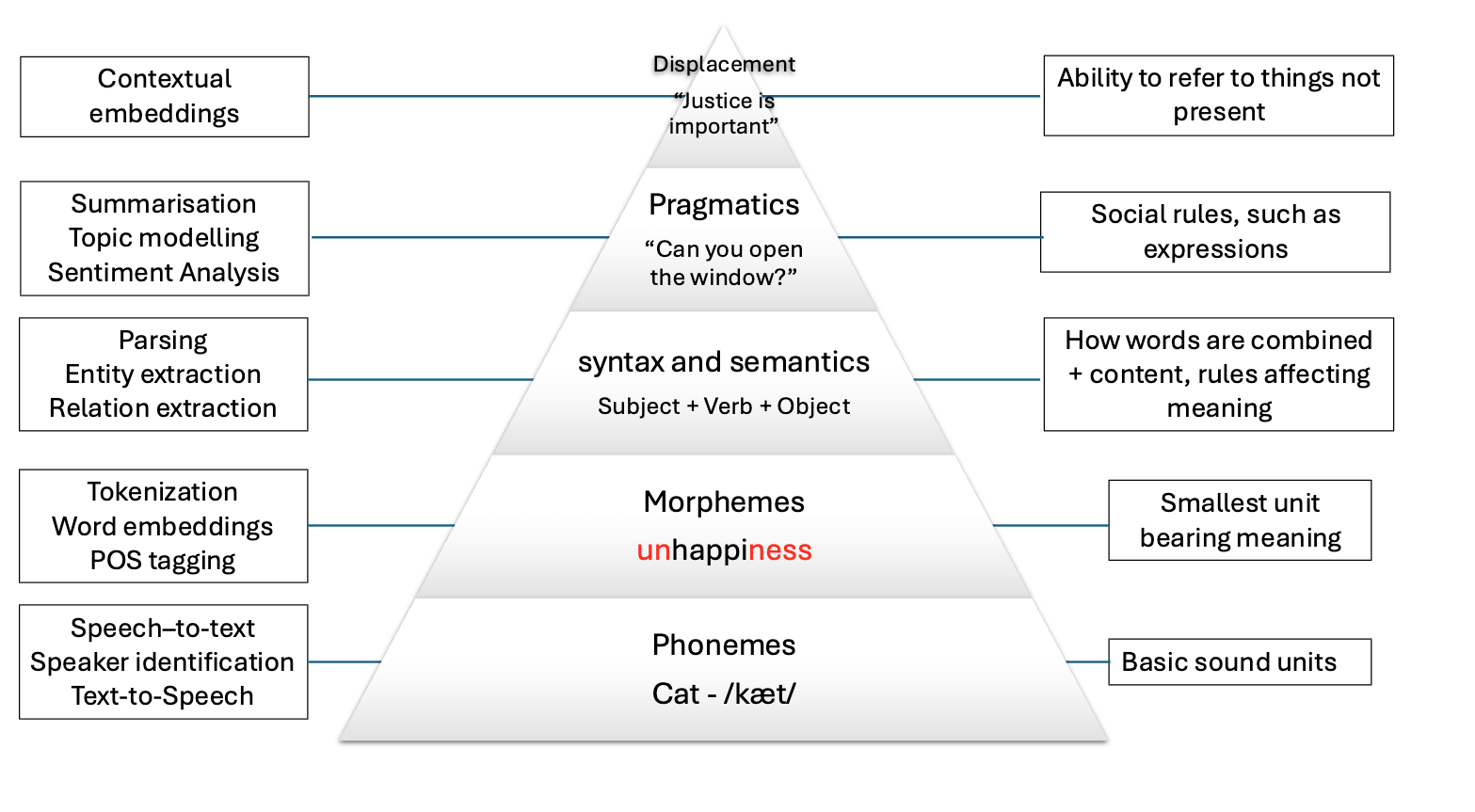

The basic elements of written languages are characters, a sequence of characters form words, and words in turn denote objects, concepts, events, actions and ideas (Goldberg, 2016). Subsequently words form phrases and sentences which are used in communication and depend on the context in which they are used. We as humans derive the meaning of utterances from interpreting contextual information that is present at different levels at the same time:

The first two levels refer to spoken language only, and the other four levels are present in both speech and text. Because in principle machines do not have access to the same levels of information that we do (they can only have independent audio, textual or visual inputs), we need to come up with clever methods to overcome this significant limitation. Knowing the levels of language is important so we consider what kind of problems we are facing when attempting to solve our NLP task at hand.

Ambiguity

The disambiguation of meaning is usually a by-product of the context in which utterances are expressed and also the historic accumulation of interactions which are transmitted across generations (think for instance to idioms – these are usually meaningless phrases that acquire meaning only if situated within their historical and societal context). These characteristics make NLP a particularly challenging field to work in.

We cannot expect a machine to process human language and simply understand it as it is. We need a systematic, scientific approach to deal with it. It’s within this premise that the field of NLP is born, primarily interested in converting the building blocks of human/natural language into something that a machine can understand.

The image below shows how the levels of language relate to a few NLP applications:

Levels of ambiguity

Discuss what the following sentences mean. What level of ambiguity do they represent?:

“The door is unlockable from the inside.” vs “Unfortunately, the cabinet is unlockable, so we can’t secure it”

“I saw the cat with the stripes” vs “I saw the cat with the telescope”

“Please don’t drive the cat to the vet!” vs “Please don’t drive the car tomorrow!”

“I never said she stole my money.” (re-write this sentence multiple times and each time emphasize a different word in uppercases).

This is why the previous statements were difficult:

- “Un-lockable vs Unlock-able” is a Morphological ambiguity: Same word form, two possible meanings

- “I saw the cat with the telescope” has a Syntactic ambiguity: Same sentence structure, different properties

- “drive the cat” vs “drive the car” shows a Semantic ambiguity: Syntactically identical sentences that imply quite different actions.

- “I NEVER said she stole MY money.” is a Pragmatic ambiguity: Meaning relies on word emphasis

Whenever you are solving a specific task, you should ask yourself what kind of ambiguity can affect your results, and to what degrees? At what level are your assumptions operating when defining your research questions? Having the answers to this can save you a lot of time when debugging your models. Sometimes the most innocent assumptions (for example using the wrong tokenizer) can create enormous performance drops even when the higher level assumptions were correct.

Sparsity

Another key property of linguistic data is its sparsity. This means that if we are hunting for a specific phenomenon, we may often realize it barely occurs inside a vast amount of text. Imagine we have the following brief text and we are interested in pizzas and hamburgers:

PYTHON

# A mini-corpus where our target words appear

text = """

I am hungry. Should I eat delicious pizza?

Or maybe I should eat a juicy hamburger instead.

Many people like to eat pizza because is tasty, they think pizza is delicious as hell!

My friend prefers to eat a hamburger and I agree with him.

We will drive our car to the restaurant to get the succulent hamburger.

Right now, our cat sleeps on the mat so we won't take him.

I did not wash my car, but at least the car has gasoline.

Perhaps when we come back we will take out the cat for a walk.

The cat will be happy then.

"""We can first use spaCy to tokenize the text and do some direct word count:

PYTHON

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

doc = nlp(text)

words = [token.lower_ for token in doc if token.is_alpha] # Filter out punctuation and new lines

print(words)

print(len(words))We have in total 104 words, but we actually want to know how many times each word appears. For that we use the Python Counter and then we can visualize it inside a chart with matplotlib:

PYTHON

from collections import Counter

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

word_count = Counter(words).most_common()

tokens = [item[0] for item in word_count]

frequencies = [item[1] for item in word_count]

plt.figure(figsize=(18, 6))

plt.bar(tokens, frequencies)

plt.xticks(rotation=90)

plt.show()This bar chart shows us several things about sparsity, even with such a small text:

The most common words are filler words such as “the”, “of”, “not” etc. These are known as stopwords because such words by themselves generally do not hold a lot of information about the meaning of the piece of text.

The two concepts (hamburger and pizza) we are interested in, appear only 3 times each, out of 104 words (comprising only ~3% of our corpus). This number only goes lower as the corpus size increases

There is a long tail in the distribution, where actually a lot of meaningful words are located.

Stop Words

Stop words are extremely frequent syntactic filler words that do not provide relevant semantic information for our use case. For some use cases it is better to ignore them in order to fight the sparsity phenomenon. However, consider that in many other use cases the syntactic information that stop words provide is crucial to solve the task.

SpaCy has a pre-defined list of stopwords per language. To explicitly load the English stop words we can do:

PYTHON

from spacy.lang.en.stop_words import STOP_WORDS

print(STOP_WORDS) # a set of common stopwords

print(len(STOP_WORDS)) # There are 326 words considered in this listYou can also manually extend the list of stop words if you are interested in ignoring other unlisted terms that you encounter in your data.

Alternatively, you can filter out stop words when iterating your tokens (remember the spaCy token properties!) like this:

Sparsity is closely related to what is frequently called domain-specific data. The discourse context in which language is used varies importantly across disciplines (domains). Take for example law texts and medical texts which are typically filled with domain-specific jargon. We should expect the top part of the distribution to contain mostly the same words as they tend to be stop words. But once we remove the stop words, the top of the distribution will contain very different content words.

Also, the meaning of concepts described in each domain might significantly differ. For example the word “trial” refers to a procedure for examining evidence in court, but in the medical domain this could refer to a clinical “trial” which is a procedure to test the efficacy and safety of treatments on patients. For this reason there are specialized models and corpora that model language use in specific domains. The concept of fine-tuning a general purpose model with domain-specific data is also popular, even when using LLMs.

Discreteness

There is no inherent relationship between the form of a word and its meaning. For this reason, by syntactic or lexical analysis alone, there is no automatic way of knowing if two words are similar in meaning or how they relate semantically to each other. For example, “car” and “cat” appear to be very closely related at the morphological level, only one letter needs to change to convert one word into the other. But the two words represent concepts or entities in the world which are very different. Conversely, “pizza” and “hamburger” look very different (they only share one letter in common) but are more closely related semantically, because they both refer to typical fast foods.

How can we automatically know that “pizza” and “hamburger” share more semantic properties than “car” and “cat”? One way is by looking at the context (neighboring words) of these words. This idea is the principle behind distributional semantics, and aims to look at the statistical properties of language, such as word co-occurrences (what words are typically located nearby a given word in a given corpus of text), to understand how words relate to each other.

Let’s keep using the list of words from our mini corpus:

Now we will create a dictionary where we accumulate the words that appear around our words of interest. In this case we want to find out, according to our corpus, the most frequent words that occur around pizza, hamburger, car and cat:

PYTHON

target_words = ["pizza", "hamburger", "car", "cat"] # words we want to analyze

co_occurrence = {word: [] for word in target_words}

co_occurrenceWe iterate over each word in our corpus, collecting its surrounding

words within a defined window. A window consists of a set number of

words to the left and right of the target word, as determined by the

window_size parameter. For example, with window_size = 3, a

word W has a window of six neighboring words—three

preceding and three following—excluding W itself:

PYTHON

window_size = 3 # How many words to look at on each side

for i, word in enumerate(words):

# If the current word is one of our target words...

if word in target_words:

start = max(0, i - window_size) # get the start index of the window

end = min(len(words), i + 1 + window_size) # get the end index of the window

context = words[start:i] + words[i+1:end] # Exclude the target word itself

co_occurrence[word].extend(context)

print(co_occurrence)We call the words that fall inside this window the

context of a target word. We can already see other

interesting related words in the context of each target word, but a lot

of non interesting stuff is in there. To obtain even nicer results, we

can delete the stop words from the context window before adding it to

the dictionary. You can define your own stop words, here we use the

STOP_WORDS list provided by spaCy:

PYTHON

from spacy.lang.en.stop_words import STOP_WORDS

co_occurrence = {word: [] for word in target_words} # Empty the dictionary

window_size = 3 # How many words to look at on each side

for i, word in enumerate(words):

# If the current word is one of our target words...

if word in target_words:

start = max(0, i - window_size) # get the start index of the window

end = min(len(words), i + 1 + window_size) # get the end index of the window

context = words[start:i] + words[i+1:end] # Exclude the target word itself

context = [w for w in context if w not in STOP_WORDS] # Filter out stop words

co_occurrence[word].extend(context)

print(co_occurrence)Our dictionary keys represent each word of interest, and the values are a list of the words that occur within window_size distance of the word. Now we use a Counter to get the most common items:

PYTHON

# Print the most common context words for each target word

print("Contextual Fingerprints:\n")

for word, context_list in co_occurrence.items():

# We use Counter to get a frequency count of context words

fingerprint = Counter(context_list).most_common(5)

print(f"'{word}': {fingerprint}")OUTPUT

Contextual Fingerprints:

'pizza': [('eat', 2), ('delicious', 2), ('tasty', 2), ('maybe', 1), ('like', 1)]

'hamburger': [('eat', 2), ('juicy', 1), ('instead', 1), ('people', 1), ('agree', 1)]

'car': [('drive', 1), ('restaurant', 1), ('wash', 1), ('gasoline', 1)]

'cat': [('walk', 2), ('right', 1), ('sleeps', 1), ('happy', 1)]As our mini experiment demonstrates, discreteness can be combatted with statistical co-occurrence: words with similar meaning will occur around similar concepts, giving us an idea of similarity that has nothing to do with syntactic or lexical form of words. This is the core idea behind most modern semantic representation models in NLP.

NLP Libraries

Related to the need of shaping our problems into a known task, there

are several existing NLP libraries which provide a wide range of models

that we can use out-of-the-box (without further need of modification).

We already saw simple examples using spaCy for English and

MicroTokenizer for Chinese. Again, as a non-exhaustive

list, we mention some widely used NLP libraries in Python:

Linguistic Resources

There are also several curated resources (textual data) that can help solve your NLP-related tasks, specifically when you need highly specialized definitions. An exhaustive list would be impossible as there are thousands of them, and also them being language and domain dependent. Below we mention some of the most prominent, just to give you an idea of the kind of resources you can find, so you don’t need to reinvent the wheel every time you start a project:

- HuggingFace Datasets: A large collection of datasets for NLP tasks, including text classification, question answering, and language modeling.

- WordNet: A large lexical database of English, where words are grouped into sets of synonyms (synsets) and linked by semantic relations.

- Europarl: A parallel corpus of the proceedings of the European Parliament, available in 21 languages, which can be used for machine translation and cross-lingual NLP tasks.

- Universal Dependencies: A collection of syntactically annotated treebanks across 100+ languages, providing a consistent annotation scheme for syntactic and morphological properties of words, which can be used for cross-lingual NLP tasks.

- PropBank: A corpus of texts annotated with information about basic semantic propositions, which can be used for English semantic tasks.

- FrameNet: A lexical resource that provides information about the semantic frames that underlie the meanings of words (mainly verbs and nouns), including their roles and relations.

- BabelNet: A multilingual lexical resource that combines WordNet and Wikipedia, providing a large number of concepts and their relations in multiple languages.

- Wikidata: A free and open knowledge base initially derived from Wikipedia, that contains structured data about entities, their properties and relations, which can be used to enrich NLP applications.

- Dolma: An open dataset of 3 trillion tokens from a diverse mix of clean web content, academic publications, code, books, and encyclopedic materials, used to train English large language models.

What did we learn in this lesson?

NLP is a subfield of Artificial Intelligence (AI) that, using the help of Linguistics, deals with approaches to process, understand and generate natural language

Linguistic Data has special properties that we should consider when modeling our solutions

Key tasks include language modeling, text classification, token classification and text generation

Deep learning has significantly advanced NLP, but the challenge remains in processing the discrete and ambiguous nature of language

The ultimate goal of NLP is to enable machines to understand and process language as humans do