Managing Virtual Environments

Last updated on 2026-02-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I make sure the whole team (or lab) gets the same results?

- How can I simplify setup and dependencies for people to use my code or reproduce my results?

Objectives

- Identify an environment, dependencies, and an environment manager.

- Install an older version of Python.

- Use

virtualenvand/orcondato create an environment per project. - Store a project’s dependencies.

- Install dependencies for a project.

Major Python versions

Let’s assume that you are using a certain package in your data analysis project. That package may be required to run a very specialized algorithm or to process some file format that is specific of your study domain. However, upon trying to install the package (with a tool such as Pip, for example), you discover some sort of error. This error may be upon the import, or even during the installation process.

This can be a common occurrence when working on programming projects, regardless of which language is being used. In Python, errors can come up because of version conflicts, that is, two or more packages require different versions of the same dependency. A dependency is an independent package that another package requires to run. By logic, the base dependency of all Python packages is the Python language itself. In order to run a Python project, we need Python to be installed. However, there are important differences between major versions of Python, specially between versions 2 and 3. From January 2020, Python 2 has been deprecated in favour of Python 3, and there is even an official guide and package for porting code from one version to the other.

There are plenty of systems running Python 2 in the wild, specially Python 2.7. It is common to have a “system-level” installation of the Python language in an older version. Most modern Python packages, however, may only support Python 3, as it is the current (and recommended) version of the language. In contrast, there are also older Python packages that only run on Python 2, and thus may not run on our system if we are currently using Python 3.

How can we deal with that?

Virtual environments

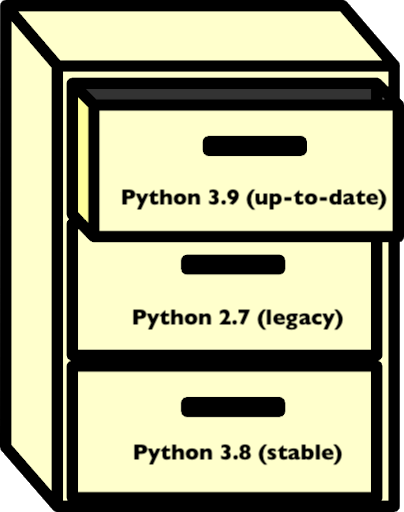

The answer to that is using virtual environments. We can think of an environment like a filing cabinet inside our computer: for each drawer, we have an installation of Python, plus a number of additional packages.

Packages that are installed in an environment are restricted to that environment, and will not affect system-level installs. Being able to isolate the installation of a specific version of Python or of a certain set of Python packages is very important to organise our programming environment and to prevent conflicts.

Whenever we activate a virtual environment, our system will start using that version of Python and packages installed in that environment will become available. Environments can also be saved so that you can install all of the packages and replicate the environment on a new system.

Why use virtual environments?

When we are unfamiliar with virtual environments, they may seem like an unnecessary hurdle. If the code runs on our current environment, why bother with the extra work of creating or using a different one? There are many reasons to use a virtual environment:

- to prevent conflicts with system-level installations;

- to ensure consistency in the code that we deliver, i.e.: keep it compatible with the same versions;

- to install our code in different environments, such as a server or cloud platform;

- to be able to share our environment with others (and prevent “works on my machine” errors).

Having isolated environments for each project greatly improves the organisation of our development environment. If something goes wrong in an environment (for example, the installation of a package breaks, or there is a version conflict between distinct dependencies), we can simply delete that environment and recreate it. The rest of our system is not affected or compromised. This can be critical in multi-user environments.

Overall, we only need to learn the basics about virtual environments to be able to use them effectively. So, there is great benefit with relatively low effort.

We can use the command-line to see which Python version is currently being used. This is the Python version that is used to execute any scripts or Python files that we run from the command-line. There are many ways to do that, but a simple one is to run:

on Mac or LINUX, or:

where pythonIn Windows machines. The which and where

commands point to the Python executable that is

currently active. If we are using a virtual environment, that file will

be inside our environment directory. If we see something like

/usr/bin/python, it is likely that we are using a

system-level version of Python. If you are using an Anaconda

distribution of Python, it is likely that you will see

<path to your anaconda install>/bin/python.

Note: these commands can also be used to locate other executables.

Dependencies

We’ve seen that dependencies are independent packages that are required for another package to run. Think of a particular package, either one that you want to create or one that you often use:

- what dependencies does it have?

- why is it important to keep track of these dependencies?

- what may happen if a dependency goes through a major version update?

- All Python packages obviously have the Python language as a dependency. For data analysis and scientific Python projects, a very common dependency is the NumPy package, that provides the basis for numerical computing in Python, and additionally other common libraries of the scientific Python stack, such as Pandas and Matplotlib.

- Keeping track of dependencies matters because our project depends on them to run correctly. If we are trying use a function or method from a dependency that behaves differently in different versions, we may get unexpected results. Also, it’s important to know our dependencies’ dependencies, which may sound like a lot, but it’s something occurs very often. If our dependency requires a package, then we also require that package.

- If a dependency goes through a major version update, such as Python 2 to Python 3, there may be breaking changes in downstream packages. If this happens for our package, we should test the package accordingly to see if everything works as expected. Testing software is a vast topic and we can leave it for now, but it is important to have that in mind when working with dependencies.

Environment and package managers

There are different strategies to deal with Python environments. We

are going to focus on two of them: virtualenv and

conda.

virtualenvis a tool to create isolated Python environments. It is so widespread that a subset of it has been integrated into the Python standard library under the venv module.virtualenvusespip, that we’ve discussed previously, to install and manage packages inside an environment. Therefore,virtualenvis an environment manager that is compatible withpip, a package manager.condais a tool from the Anaconda distribution that is both an environment and package manager. Packages can be installed in Conda environments using bothpipandconda. There are a fews advantages of using Conda for installations, such as support for third-party packages (that aren’t available on PyPI) and automatic dependency solving. This comes at the disadvantage of being heavier and usually slower thanvirtualenv.

Because we are already familiar with pip, we can start

off by using virtualenv to learn how environments work in

practice. We’ll have a look at Conda environments later on.

Create an environment

Before we create an environment, let’s see what happens when we import one of our favorite packages. In a Python interpreter:

That should work, because we have the package installed on our system. If not, use a package you know you have installed, or install NumPy.

Next, we’ll create an environment named myenv:

We could simply run virtualenv myenv, but the

-p python3 flag ensures that we create it with Python

3.

You will notice that a myenv/ folder has been created in

the working directory. We can then activate our environment by

running:

Now we see that the CLI changes to show the environment name! We can

also run the where or which command again to

see that our Python executable has been changed.

The output should look something like

<working directory>/myenv/bin/python.

Let’s start another Python interpreter (simply type

python) and try to import NumPy again:

It does not work! This is expected, because we have just created this

environment from scratch. It only contains the base Python installation.

To install NumPy in this environment, we must use pip:

If we open a new Python interpreter, NumPy can now be imported.

Listing packages and the requirements file.

We can check which packages are installed in our current environment

using the pip freeze command. If we wish to save that list

in a file for later use, we can use a UNIX redirect statement

(>). More on those on the SWC

Shell Novice lesson.

This saves the list of packages and respective versions in the

requirements.txt file. Requirement files are very common in

Python projects, as they are a simple way of specifying the project’s

dependencies.

Deactivate an environment

When you’re done with an environment, you can exit with the

deactivate command.

Not how the environment name disappears from the Shell prompt.

Default environment

Note that an environment is only activated in the current Terminal

window. If you open a new Terminal, you’ll be back to your default

environment. This could be, for example, the base

environment if you have Anaconda installed, or your system’s default

Python environment.

Using virtual environments

To use what we’ve learned so far, try doing the following:

- Find a project that interests you.

- Download or clone the project’s repository.

- Create a new virtual environment for the project.

- Use the project’s

requirements.txtfile to install the dependencies.

Hint: use pip install -h to see the

possible options for the pip install command.

We can use the example-python-project from Episode 02 to demonstrate this:

BASH

git clone https://github.com/vinisalazar/example-python-project.git

cd example-python-project

virtualenv example-env

source example-env/bin/activateThe -r flag in the pip install command

allows installing a project’s requirements from a text file:

These are the basics of using virtualenv to create

virtual environments. Alternatively, we could also use

conda, which is a more advanced package and environment

manager. conda has several advantages over

virtualenv, at the cost of being heavier and slower.

Conda environments

conda works similarly to virtualenv, but we

use the conda command for managing both packages and

environments (with different subcommands, such as

conda create, conda install, etc). If you are

using Python for data analysis, chances are that you have it installed

through Anaconda or Miniconda, as they are very popular distributions of

Python. Both Anaconda and Miniconda come with the conda

environment manager, that can be used from the command-line (if you have

(base) in your Shell prompt, that means it’s likely using

the base, or default, conda environment). Try

typing conda in your Terminal. You should see something

like the following:

OUTPUT

usage: conda [-h] [-V] command ...

conda is a tool for managing and deploying applications, environments and packages.

Options:

positional arguments:

command

clean Remove unused packages and caches.

compare Compare packages between conda environments.

config Modify configuration values in .condarc. This is modeled

after the git config command. Writes to the user .condarc

file (/Users/vini/.condarc) by default.

create Create a new conda environment from a list of specified

packages.

help Displays a list of available conda commands and their help

strings.

info Display information about current conda install.

init Initialize conda for shell interaction. [Experimental]

install Installs a list of packages into a specified conda

environment.

list List linked packages in a conda environment.

package Low-level conda package utility. (EXPERIMENTAL)

remove Remove a list of packages from a specified conda environment.

uninstall Alias for conda remove.

run Run an executable in a conda environment. [Experimental]

search Search for packages and display associated information. The

input is a MatchSpec, a query language for conda packages.

See examples below.

update Updates conda packages to the latest compatible version.

upgrade Alias for conda update.

optional arguments:

-h, --help Show this help message and exit.

-V, --version Show the conda version number and exit.Differently than virtualenv, when we create a new

environment with Conda, the folder containing the environment is not

created in the working directory, but rather in the envs/

directory in thefolder where Anaconda or Miniconda is installed. Let’s

create a Conda environment from scratch to demonstrate this.

Creating and managing Conda environments

First, check out your current Python interpreter using

which python or where python. If you are still

using an environment created with virtualenv, deactivate it

using the deactivate command. Now, create a new environment

using conda create:

After a while, a prompt should appear confirming if you want to

create the environment. Simply type y and press Enter.

In this command, the -n flag specifies the

name of our environment, and can be set to anything we

like. After the environment’s name, we specify any packages that we want

to install. In the example above, our command specifies that we want the

example-env to have Python and the Python version should be

3.9. We could also specify python=3 if we didn’t care for

the minor version number.

To activate our newly created Conda environment, we use

conda activate:

Similar to virtualenv, we should see

(example-env) in our prompt, meaning the environment is

active. If we run which python again, it should point for a

Python installation inside the envs/ directory in our

Anaconda folder:

OUTPUT

<path to anaconda folder>/envs/example-env/bin/pythonInstalling packages from Conda channels

Now that we’ve activated our example environment, we can use the

conda install command to install packages. If we consider

the same example-python-project used in the previous

examples, we can check the requirements file and see that it has four

dependencies: Pandas, NumPy, Matplotlib, and Seaborn. We could install

the dependencies like this:

Now, there are a couple of details to unpack in this simple command.

First, why did we only include Pandas and Seaborn in our command? Why

didn’t we include Matplotlib and NumPy? Second, what does the

-c conda-forge option do?

The answer to the first question is one of the cool things about

using Conda: it automatically downloads dependencies of packages we are

attempting to install. In this case, NumPy is a dependency of Pandas and

Matplotlib is a dependency of Seaborn. Thus, we only need to install

Pandas and Seaborn and the other two packages will automatically be

downloaded. pip also accounts for dependencies when

installing new packages, but Conda’s dependency solver

is much more sophisticated, and ensures compatibility across all

packages in our environment.

The second question is because of channels

in Conda. Here, we are using the conda-forge channel.

Channels are repositories of packages, much like PyPI is the repository

used by pip. Conda-forge is a well-stablished and

community-driven repository for Conda packages (or

recipes, as they are called). Conda-forge has an

advanced infrastructure to automatically maintain and update Conda

recipes, and is a reliable source for installing packages through Conda.

Check out their docs for

more information. Other known Conda channels include Bioconda, which specializes in

bioinformatics software, and the R channel, that

provides packages for the R programming language.

Searching for Conda packages

To check if a package can be installed with Conda, go to https://anaconda.org/ and

use the search bar to search for the package’s name. If the package is

available through a Conda channel, it’ll be listed here. By clicking on

the package name, you can see the exact conda command to

install it.

After running the conda install command, we will get a

prompt to confirm the installation, much like we did the

conda create command. These prompts can be skipped by

adding a -y flag to either commands.

Listing packages and exporting a Conda environment

To list available packages in a Conda environment, we can run:

Note that the output of conda list is more detailed than

pip freeze. It also includes build specification IDs and

channel information. To export that list to a file, we can use the

conda env export command:

Where the -f flag specifies the name of our output file

and the --no-builds command specifies that we don’t wish to

include the build specification numbers in our output (although it can

be omitted). If we inspect that file, we can note that it contains some

extra information than the output of pip freeze, such as

the environment name and Conda channels that are included in the export

(these two parameters can be configured with the

conda env export command.)

The resulting YAML file can be used

to recreate the environment in other systems, much like the

pip install -r requirements.txt command. For that, we can

run:

And the environment will be recreated from the specified dependencies.

Conclusion

Wow, that was a lot of commands in a single episode. And those were

only the basics of using virtual environments! However, we mustn’t fret.

It doesn’t matter if we use conda or

virtualenv, and different situations will call for

different tools, the important thing to remember is to understand the

importance of using virtual environments. Having our

environment isolated from the rest of our system is really good to

prevent version conflicts, and “pinning” our dependencies in a

requirements.txt or environment.yml can be

very helpful for other users to install the necessary packages to run

our code.

Official docs

For more information on conda and

virtualenv, check out the official documentation pages:

- A Python dependency is an independent package that a given project requires to be able to run.

- An environment is a directory that contains a Python installation, plus a number of additional packages.

- An environment manager enables one-step installing and documentation of dependencies, including versions.

-

virtualenvis a tool to create lightweight Python virtual environments. -

condais a more advanced environment and package manager that is included with Anaconda. - Isolating our environment can be helpful to keep our system organized.

- Dependencies can be ‘pinned’ to files such as

requirements.txtorenvironment.yml.