Introduction to Open Science and FAIR principles

Last updated on 2024-05-01 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is Open Science?

- How can I benefit from Open Science?

- What are the FAIR guidelines?

- Why is being FAIR important?

Objectives

- Identify the components of the Open Science movement, their goals, and motivations.

- Explain the key benefits of Open Science.

- Recognize the barriers and challenges associated with adopting Open Science practices.

- Identify common issues that hinder data reusability.

- Understand the FAIR principles.

(10 min teaching)

Science thrives on the exchange and development of ideas. The most efficient scientific progress involves well-informed questions and experiments, which necessitates the free exchange of data and information.

All practices that make knowledge and data freely available fall under the umbrella term of Open Science/Open Research. It fosters greater reproducibility, transparency, and accessibility in science. As science becomes more open, the way we conduct and communicate scientific findings continuously evolves.

What is Open Science

Open science is the movement to make scientific research (including publications, data, physical samples, and software) and its dissemination accessible to all levels of an inquiring society, amateur or professional.

Open Science represents a new approach to the scientific process based on collaborative work and utilizing digital technologies and new collaborative tools to disseminate knowledge.

Open science promotes transparent and accessible knowledge that is shared and developed through collaborative networks.

Characteristics:

- Utilizing web-based tools to facilitate information exchange and scientific collaboration

- Transparency in experimental methodology, observations, and data collection

- Public availability and reusability of scientific data, methods, and communications

- Diverse outputs and target audiences

What is the Open Science movement?

The distribution of knowledge has always had room for improvement. While the internet was initially developed for military purposes, it was ultimately used for communication between scientists, providing a viable path to transform how science is disseminated.

The momentum has grown alongside a shift in how science is communicated, reflecting the needs of research communities. Open Science addresses many of the pressing issues we face today, such as impact factors, data reusability, the reproducibility crisis, and trust in the public science sector.

Open Science is the movement to increase transparency and reproducibility of research through the adoption of open best practices.

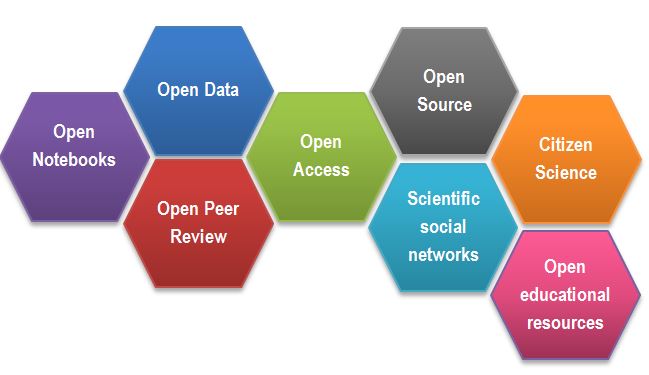

After Gema Bueno de la Fuente

Open Science Building Blocks

Open Access: Research outputs are hosted in a way that makes them accessible to everyone. Traditionally, Open Access referred to journal articles, but now encompasses books, chapters, or images.

Open Data: Data is freely and readily available to access, reuse, and share. Smaller data sets were often included as supplemental materials alongside articles in journals. However, they should be hosted on dedicated platforms for more convenient and improved access.

Open Software: Software with readily available source code; others can freely use, modify, and share it. Examples include the coding language and supporting software R and RStudio, as well as image analysis software like Fiji/ImageJ.

Open Notebooks: Lab notebooks hosted online, readily accessible to all. These are popular among some large funding bodies and allow anyone to comment on any stage of the experimental record.

Open Peer Review: A system where peer review reports are published alongside the research work. This can include reviewers’ reports, correspondence between involved parties, rebuttals, editorial decisions, etc.

Citizen Science: Lay people contribute to scientific research, most commonly in data collection or image analysis. Platforms like https://www.zooniverse.org/ connect projects with interested laypeople who can actively participate in research, helping to generate and/or process data that would be unachievable by a single person.

Scientific social networks: Networks of researchers, often meeting locally in teams but also connected online, foster open discussions on scientific issues. Many researchers use traditional social media platforms for this purpose, such as Twitter, Instagram, various subreddits, discussion channels on Slack/Discord, etc. There are also dedicated spaces like https://www.researchgate.net/.

Open Educational Resources: Educational materials that are free for anyone to access and use for learning. These can be anything from talks, instructional videos. This very course is a perfect example of that!

Benefits of Open Science

Possible benefits and consequences for each Open Science module:

Open Access

- Faster dissemination of knowledge

- Levels the playing field for underfunded institutions that wouldn’t otherwise be able to access research behind paywalls

- Prevents articles from being paid for “three times” (first to produce, second to publish, third to access) by institutions

- Increases access to work by others, leading to greater exposure and citations

- Provides access to research for laypeople, thus increasing public awareness of science

Open Data

- Ensures data isn’t lost over time - promotes reusability

- Accelerates scientific discovery

- Provides value for money and reduces redundancy

- Allows for statistical re-analysis of data to validate findings

- Gives access to datasets not published in papers (e.g., negative results, large screening data sets)

- Provides a way to generate new hypotheses

- Enables the combination of multiple data sources to address questions, providing greater power than a single data source

Open Software

- Excellent resource for learning programming skills

- The ability to modify software fosters a supportive community of users and rapid innovation

- Saves time

- Enables faster bug fixes

- Encourages better error scrutiny

- Using the same software/code allows for better reproducibility between experiments

- Requires funding to maintain and update software

Open Notebooks

- Promotes 100% transparent science, allowing input from others at early stages of experiments

- Provides a source for learning about the scientific process

- Allows access to experiments and data that otherwise might never get published

- Provides access to ‘negative’ results and failed experiments

- Anyone, anywhere in the world, can access projects at any time, enabling simultaneous input from many users

- Offers the possibility of immediate feedback

- Provides thorough evidence of the originality of ideas and experiments, reducing the impact of “scooping”

Open Peer Review

- Visibility leads to more constructive reviews

- Mitigates against editorial conflicts of interest and/or biases

- Mitigates against reviewer conflicts of interest and/or biases

- Allows readers to learn and benefit from reviewers’ comments

Open Educational Materials

- Fosters collaboration between educators and others

- Clearly demonstrates how methods are taught (e.g., Carpentries materials), which can be reproduced anywhere, anytime

- Protects materials from becoming technologically obsolete

- Authors who prepare or contribute materials can receive credit (e.g., GitHub)

- Enables the reuse of animations and excellent materials (why reinvent the wheel?)

Motivation: Money (8 min teaching)

We must consider the ethical implications that accompany the research and publication process. Charities and taxpayers fund research, and then pay again to access the research they already funded.

From an economic viewpoint, scientific outputs generated by public research are a public good that everyone should be able to use at no cost.

According to an EU report titled “Cost-benefit analysis for FAIR research data: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d375368c-1a0a-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1”, €10.2 billion is lost every year due to inaccessible data (with an additional €16 billion lost if we consider data reuse and research quality).

Open Science aims to make research and research data accessible to those who funded the research, such as charities and taxpayers.

The majority of large funding bodies in the UK and other countries are now making Open Access publication a condition of funding. As a result, Open Access is becoming the most widespread aspect of the Open Science movement, adopted by the majority of researchers.

Personal motivators

Open Science offers advantages to many stakeholders in science (including the research community, funding bodies, the public, and even journals), leading to a push for widespread adoption of Open Science practices.

Large UK funding bodies like The Wellcome Trust are strong supporters of Open Science. The example of Open Access demonstrates that enforcement by funders (the stick) can lead to widespread adoption. But what about the personal motivators, the carrots?

Exercise 1: Personal benefits of being “open” (5 min)

Open Science practices offer a variety of advantages for researchers. Read through the list below and consider which benefits resonate most with you.

Select two the most important/attractive for you and mark them with +1, select the two least important for you and mark them with 0

- receive higher citations

- complying with funders’ policies

- get extra value from your work (e.g. collaborators, reuse by modellers, ML specialists)

- demonstrate research impact

- save own time (reproducibility but also communication overhead)

- become pioneers

- distinguish yourself from the crowd

- plan successful research proposals

- gain valuable experience

- form community

- increased speed and/or ease of writing papers

- speed up and help with peer review

- build reputation and presence in the science community

- evidence of your scientific rigour and work ethic

- avoid embarrassment/disaster when you cannot reproduce your results

Can you think of other benefits?

How personal benefits of Open Science compare to the benefits for the (scientific) society?

(5 min teaching)

Open Science offers distinct advantages for both researchers and society at large. The public benefits from immediate access to research outputs, leading to faster scientific progress and innovation.

For researchers, the benefits take longer time, as open data and publications need to time to lead to citations, collaborations, and recognition within the scientific community

DORA: Declaration on Research Assessment

The San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) emphasizes the limitations of using metrics like Journal Impact Factors (JIF) to solely evaluate research. DORA advocates for assessing research based on its inherent merit and contributions, promoting fairer and more transparent evaluation practices. This shift acknowledges the importance of research quality, openness, and its broader societal impact.

Funders Embrace DORA Principles

Research funders worldwide are increasingly endorsing DORA principles. Leading institutions like Wellcome Trust and Cancer Research UK incorporate DORA criteria into their funding applications. These funders prioritize research outputs, mentorship contributions, and public engagement plans, supporting research that generates valuable knowledge, fosters collaboration, and benefits society.

Narrative CV as a DORA-Compliant Assessment Tool:

The Narrative CV aligns with DORA principles by focusing on key dimensions that reflect a researcher’s contributions:

- Generation of Knowledge: Acknowledging diverse outputs such as datasets, patents, and software.

- Development of Individuals and Collaborations: Highlighting mentorship and collaborative endeavors that enrich the research ecosystem.

- Societal and Economic Impact: Demonstrating the societal and economic impacts of research beyond academic circles.

- Supporting the Research Community: Engaging in open science practices and ensuring the accessibility of research outputs.

This framework prioritizes open science practices to maximize research impact and visibility. Additionally, new metrics like retweets, online views/downloads, discussions, and media coverage are considered, providing a more comprehensive understanding of research impact in the digital age.

Why Embrace Open Practices?

Open Science practices not only uphold ethical research conduct but also enhance the credibility and reach of your work. The Narrative CV and the adoption of DORA by leading funders exemplify the research community’s shift towards a more transparent and equitable assessment paradigm. Choosing open practices demonstrates not just integrity, but also a recognition that authenticity and transparency are fundamental to scientific progress. After all, timestamps and meticulous documentation make faking open practices far more difficult than simply adhering to them.

Barriers and risks of the Open Science movement:

Exercise 2: Why we are not doing Open Science already (about 5 min)

Discuss the challenges and potential drawbacks associated with Open Science practices.

- Data Sensitivity: Anonymizing data from certain sources, like administrative health records, can be complex and time-consuming.

- Intellectual Property (IP) Concerns: Researchers might hesitate to share data if it could compromise potential patents or other intellectual property.

- Misuse of Data: Open data carries a risk of misinterpretation or misuse, potentially leading to the spread of misinformation (e.g., “fake news”).

- Lack of Recognition for Negative Results: Publishing negative or inconclusive findings can be less rewarding in the current academic evaluation system.

- Time and Cost: Making research outputs open and user-friendly requires time and resources for proper data curation, storage, and dissemination. This can be especially challenging for large datasets.

- Lack of Expertise: Researchers might not have the necessary skills or training to effectively manage and share data openly.

- Fear of Criticism: The prospect of open peer review or public scrutiny can be daunting, leading some researchers to shy away from open science practices.

(8 min teaching)

There are valid reasons why some researchers hesitate to embrace Open Science entirely.

Data sensitivity is a major concern. Data privacy laws require careful handling of sensitive data, and anonymization can be a complex process.

Anonymising data to desensitise it can help overcome this barrier.

Intellectual property (IP) considerations are another hurdle. Researchers may be hesitant to share data that could compromise the patenting or commercialization of their discoveries. However, careful data filtering can often address these concerns. For IP protection it is the timeline of public disclosure that matters not fact making them public.

Pre-prints, while valuable for rapid knowledge dissemination, can be misused, particularly in fast-moving fields like public health research. Unreviewed pre-prints have the potential to mislead policymakers and the public if not interpreted with caution. This can result in political and health decision making based on faulty data, which is counter to societies’ best interest.

The fear of negative feedback can also be a barrier. However, open peer review is a crucial part of the scientific process. Identifying and correcting errors through open review strengthens research and fosters a culture of transparency.

We should seek for our work to be scrutinized and errors to be pointed out, and is the sign of a competent scientist. One should rather have errors pointed out rather than risking that irreproducible data might cause even more embarrassment and disaster.

Lack of Expertise: Researchers might not have the necessary skills or training to effectively manage and share data openly.

One of the biggest barriers are the costs involved in “being Open”. The time and financial investment required for Open Science practices can be a significant barrier. Making data readily accessible and usable takes effort, and data storage can be expensive, especially for large datasets.

For example, microscopy datasets reach sizes in terabytes, making such data accessible for 10 years involves serious financial commitment.

Being FAIR

We’ve explored the advantages of Open Science practices for both the scientific community and individual researchers. While Open Access has made recent biomedical publications readily available, the same accessibility often isn’t the case for the underlying data and software.

What is Data?

The term “scientific data” encompasses a wider range than many might initially think. It’s not limited to just numbers in spreadsheets! Data can include:

- Images: Microscopy images, but also gels, blots, and other visual representations of findings.

- Biological Information: Details about research materials, like specific strains, cell lines, or patient demographics.

- Biological Models: Computational models used in simulations or analyses.

- Protocols: Step-by-step procedures for lab experiments or data collection methods.

- Code: Scripts, analysis routines, and custom software used to generate results.

While there are specific best practices for sharing code, it’s still considered a form of research data.

Let’s delve into the challenges associated with accessing and using data from published biological research.

Exercise 3: Impossible protocol

(5 min breakout, plus 10 talking about both problems)

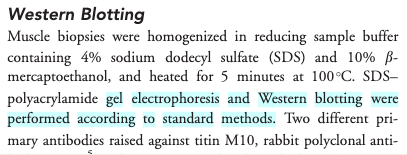

You need to do a western blot to identify Titin proteins, the largest proteins in the body, with a molecular weight of 3,800 kDa. You found an antibody sold by Sigma Aldrich that has been validated in western blots and immunofluorescence. Sigma Aldrich lists the Yu et al., 2019 paper as reference.

Find details of how to separate and transfer this large protein in the reference paper.

- Hint 1: Methods section has a Western blot analysis

subsection.

- Hint 2: Follow the references.

Would you say that the methods was Findable? Accessible? Reusable?

- Ref 17 will lead you to this paper, which first of all is not Open Access

- Access the paper through your institutions (if you can) and find the ‘Western Blotting’ protocol on page 232 which will show the following (Screenshot from the methods section from Evilä et al 2014):

Figure 1. Impossible Protocol

Figure 1. Impossible Protocol- “Western blotting were performed according to standard methods.” - with no further reference to these standard methods, describing these methods, or supplementary material detailing these methods

- This methodology is unfortunately a true dead end and we thus can’t easily continue our experiments!

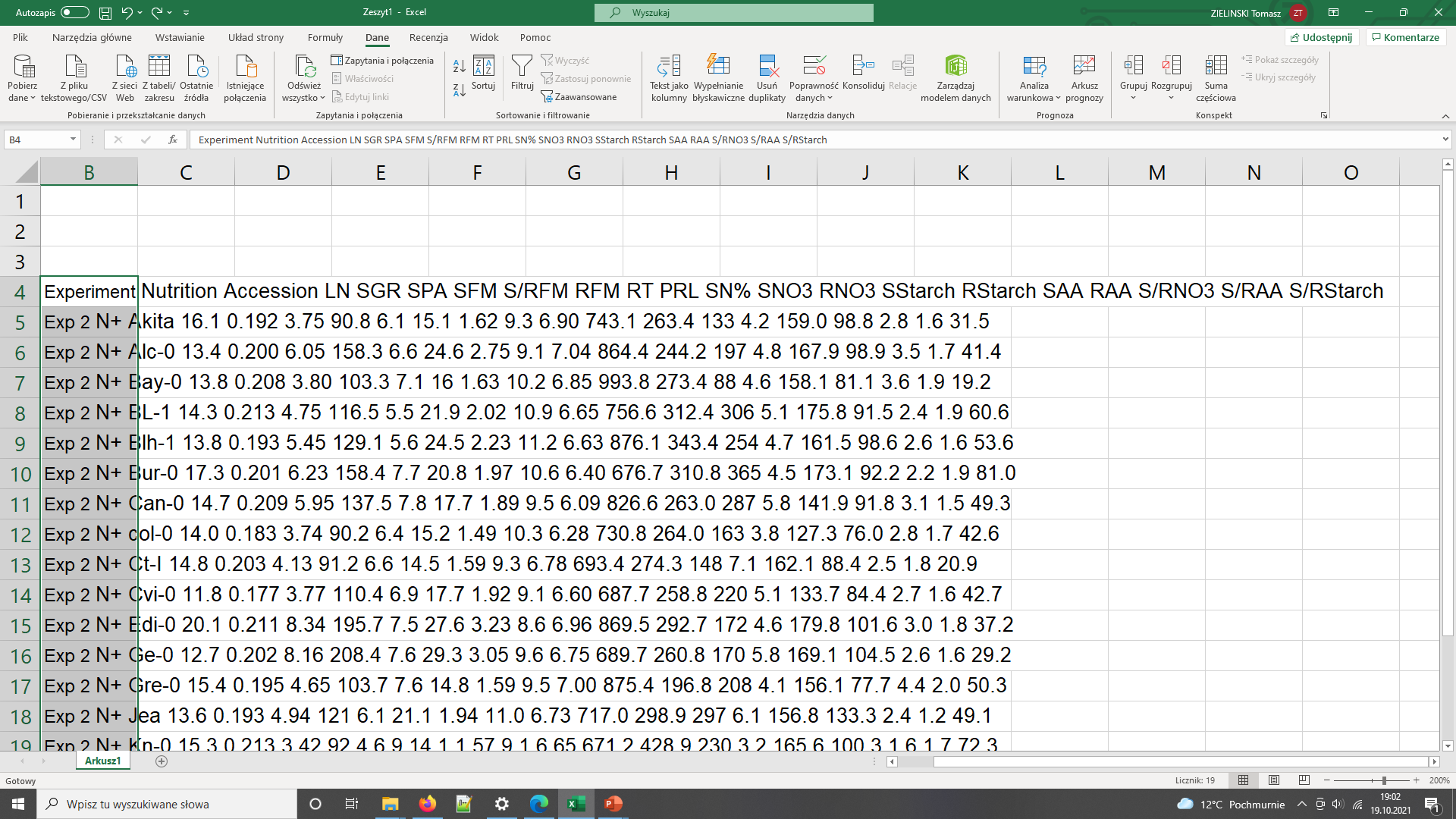

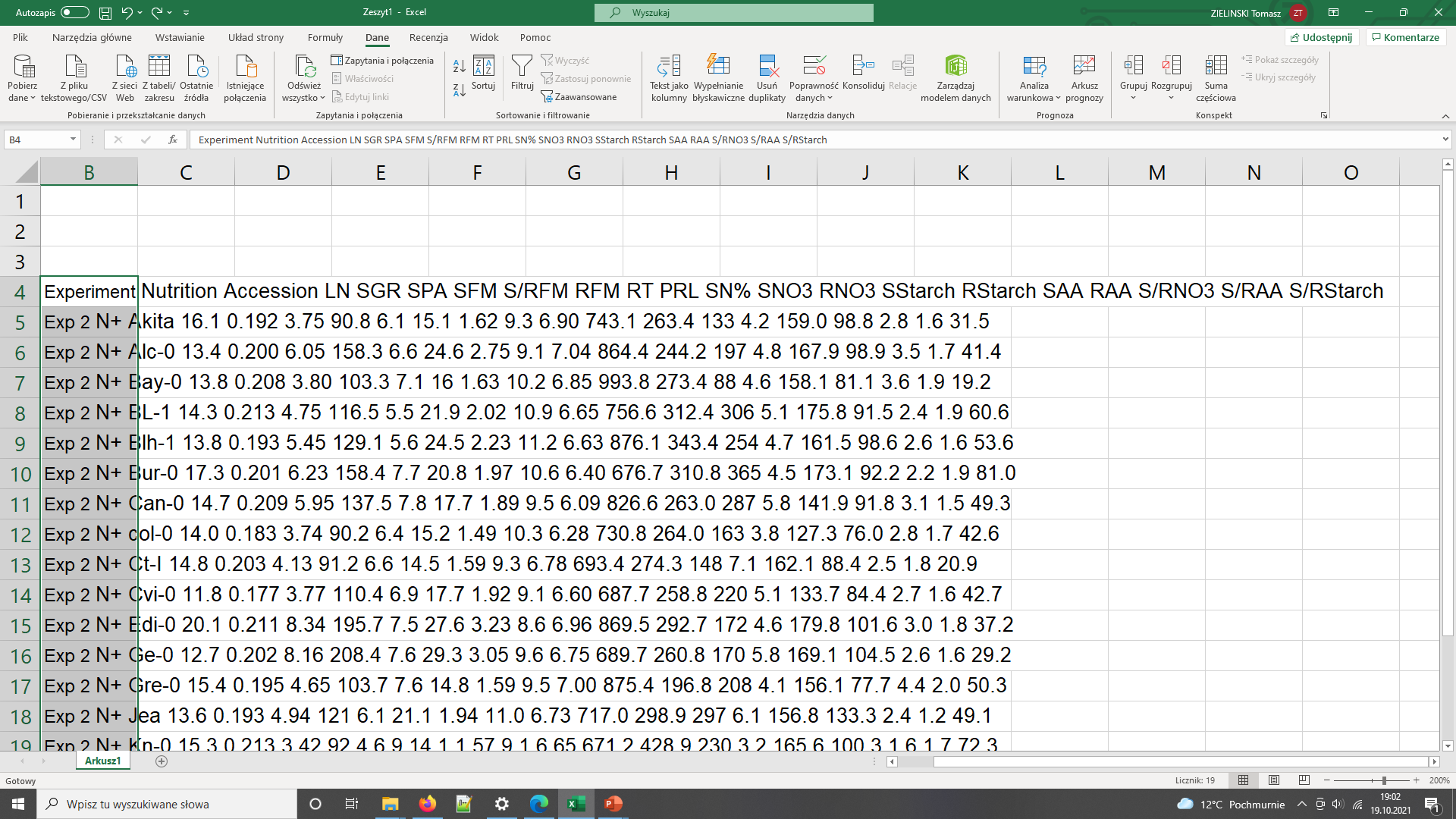

Impossible numbers

Ikram 2014 paper contains data about various metabolites in different accessions (genotypes) of Arabidopsis plant. You would like to calculate average nitrogen content in plants grown under normal and nitrogen limited conditions. Please calculate the average (over genotypes) nitrogen content for the two experimental conditions.

- Hint 1. Data are in Supplementary data

- Hint 2. Search for nitrogen in paper text to identify the correct data column.

- Finding the right table and column containing the relevant data is already problematic as the headers are obscured so they need to decoded using manuscript

- Data in pdf table so they cannot be readily used in calculations

- Depending on the software used to open (and the way the pdf was

created), the local machine international settings, copying the data

into Excel can bring unexpected results

Data needs parsing after coping to Excel

The same data copied to Excel with polish locale has been converted to dates - In general pdf tables cannot be read programmatically from R or Python.

The above examples illustrate the typical challenges in accessing research data and software.

Firstly, data, protocols, and software often lack a distinct identity, existing only as supplements to publications.

Second, accessibility and reusability are often compromised. For instance, all details might be buried within a single supporting information PDF file. These files often contain “printed” numerical tables or even source code, both of which require manual re-entry for use by others. Additionally, data may be shared in proprietary file formats specific to a particular vendor, inaccessible without the accompanying software. Finally, data files are often provided without detailed descriptions beyond the full article text, hindering reusability.

In our examples, the protocol was difficult to find (the loops), access (paywall), and reuse due to a lack of necessary details (dead-end). Similarly, in the second example, the data were not interoperable or reusable as they were only available as a figure graph.

To address these problems, the FAIR principles were designed.

In our examples, the protocol was difficult to find (the loops), difficult to access (pay wall), and not reusable as it lacked the necessary details (dead-end).

In the second example the data were not interoperable and reusable as their were only available as a figure graph.

To avoid such problems FAIR principles were designed.

After SangyaPundir

After SangyaPundir

(10 min teaching)

FAIR Principles

In 2016, the FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship: https://www.nature.com/articles/sdata201618 were published in Scientific Data. The original guideline emphasized “machine-actionability” - the ability of computer systems to automatically process data. However, the focus has shifted towards human-centric accessibility, acknowledging the limitations of user-friendly tools for standardized metadata.

Findable: Data and metadata should be easily discoverable by both humans and computers. Standardized and persistent identifiers (PIDs) and machine-readable metadata are crucial for automatic dataset and service discovery.

Accessible: (Meta)data should be retrievable using a standardized and open communication protocol (including authentication and authorization) based on their identifier. Even if the data itself becomes unavailable, the metadata should remain accessible.

Interoperable: Data should be combinable and usable with other data or tools. Open and interpretable data formats are essential for various tools. Both data and metadata should utilize vocabularies that follow FAIR principles to promote interoperability.

Reusable: FAIR aims to optimize data reuse. Well-described metadata and data facilitate replication and integration in different contexts. Clear and accessible licenses should be provided to govern (meta)data reuse.

FAIR in biological practice

Findable & Accessible

Deposit your data in a reputable external public repository.

These repositories provide persistent identifiers (PIDs) for easy discovery, along with options for cataloging, advanced metadata searching, and download statistics. Some repositories can even host private data or offer embargo periods to delay full data access.

General “data agnostic” repositories include:

*Domain-specific examples include:**

- UniProt protein data,

- GenBank sequence data,

- MetaboLights metabolomics data

- GitHub for code.

We will cover repositories in more details in a later episode.

A persistent identifier (PID) is a long-lasting reference to a digital resource. It typically consists of two parts:

- A service that locates the resource over time, even if its location changes.

- A unique identifier that distinguishes the resource or concept from others.

PIDs address the problem of accessing cited resources, particularly in academic literature, where web addresses (links) often change over time, leading to broken links.

Several services and technologies (schemes) provide PIDs for various objects (digital, physical, or abstract). One of the most common is the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) (https://www.doi.org/), recognizable by the prefix “doi.org” in web links. For instance, this link (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26978244/) resolves to the paper that describes FAIR principles.

Public repositories often maintain stable web addresses for their

content, following the convention

http://repository.address/identifier. These are often

called permalinks. For well-established services, permalinks can be

considered PIDs.

For example, this link http://identifiers.org/SO:0000167 points to a page defining the promoter role and can be used to annotate a DNA sequence performing such a role during transcription.

Interoperable

- Use common and ideally free file formats (domain-specific options might exist).

- Always use

.csvor.xlsfor numerical data. Never share data tables as Word or PDF documents. - Provide the underlying numerical data for all plots and graphs.

- Convert proprietary binary formats to open formats. For example, convert Snapgene to GenBank, or microscopy multistack images to OME-TIFF.

Reusable

Describe your data well with comprehensive metadata.

- Write a README file that describes your data.

- Use descriptive column headers in your data tables.

- Organize your data tables for analysis-friendliness (tidy data principles).

- Provide as much detail as possible through rich metadata.

- Utilize appropriate metadata formats (e.g., SBML, SBOL).

- Adhere to Minimum Information Standards (MIS) for your field.

Describing data in sufficient detail is often the most challenging aspect of data sharing. We’ll cover this in more detail later.

- Include license files.

Licenses explicitly state the conditions and terms under which your data and software can be reused. Here are some recommendations:

- For data, we recommend the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

- For code, consider a permissive open-source license such as MIT, BSD, or Apache Apache license licenses.

Copyright and data

Software code (the text itself) automatically receives default copyright protection, preventing others from copying or modifying it. Only by adding an explicit license can you permit others to reuse it.

Data, being factual, cannot be copyrighted. So why, do we need a license?

While the data itself cannot be copyrighted, the way it’s presented can be. The extent to which it’s protected ultimately needs to be settled by a court.

“Good actors” will refrain from using your data to avoid legal risks. However, “bad actors” might ignore the risk or have the resources to fight legal battles.

Exercise 4: Example of FAIR data

(5 min breakout, plus 3 min showing answers)

Zenodo is general data repository. Have a look at the dataset record with COVID-19 data: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6339631

Identify how each of F.A.I.R principles has been met.

Hint: navigate to linked github record to easily access the README

file

- F: The dataset is identified by a PID (doi). It can be found by its ID. It human accessible description and keywords, both suitable for discovery.

- A: Data can be downloaded using standard browser.

- I: Dataset entries are in common formats: csv, R, jpg

- I: Dataset is linked to publication, github record and project website

- R: The record contains rich metadata in README file, including files structure and the detailed tables formats.

- R: Data are released under open Creative Commons Attribution Licence

The FAIR acronym is sometimes accompanied with the following labels: * Findable - Citable * Accessible - Trackable and countable * Interoperable - Intelligible * Reusable - Reproducible

- Findable - Citable: Findable data has a unique identifier, ensuring proper attribution to the creators.

- Accessible - Trackable and Countable: Accessible data allows for monitoring usage statistics (e.g., downloads, user locations) to understand its reach and impact.

- Interoperable - Intelligible: Interoperable data is understandable not only by current users but also by future users, even if they lack access to the specific software used for analysis. This is achieved through the use of standard formats and clear documentation. The future you may not remember abreviations and ad-hoc conventions you used before

- Reusable - Reproducible: Well-documented data with sufficient detail allows for reproducing the experiments, facilitating verification and building upon existing knowledge. This saves time and resources.

FAIR vs Open Science (2 min teaching)

FAIR is not synonymous with Open. FAIR guidelines primarily require open access to the metadata record, describing the data’s existence, a user-friendly PID for reference, and potentially some restrictions on accessing the actual data files (e.g., login required).

However, FAIR data is well-positioned for becoming Open data. Since it’s already accessible online, uses interoperable formats, and comes with thorough documentation, transitioning to fully open access becomes a relatively simple step whenever the data owner decides it’s no longer a risk.

Conversely, Open data lacking FAIR characteristics holds minimal value. Poorly described data in non-standard formats remains unusable even if it’s publicly available.

Open Science and FAIR Quiz (5 min)

Which of the following statements about the OS and FAIR are true/false?

- Open Science relies strongly on the Internet

- Open Access eliminates publishing costs

- Open Data facilitates re-use

- Open Data can increases confidence in research findings

- In Open Peer Review, readers vote on publication acceptance

- Open Access permits the whole society to benefit from scientific findings

- Citizen Science engages the public in the research process

- Release of public datasets is important for career progression

- F in FAIR stands for free.

- Only figures presenting results of statistical analysis need underlying numerical data.

- Sharing numerical data as a .pdf in Zenodo is FAIR.

- Sharing numerical data as an Excel file via Github is not FAIR.

- Group website is a good place to share your data.

- Data should always be converted to Excel or .csv files in order to be FAIR.

- A DOI of a dataset helps in getting credit.

- FAIR data are peer reviewed.

- FAIR data accompany a publication.

- Open Science relies strongly on the Internet T

- Open Access eliminates publishing costs F

- Open Data facilitates re-use T

- Open Data increases confidence in research findings T

- In Open Peer Review, readers vote on publication acceptance F

- Open Access permits the whole society to benefit from scientific findings T

- Citizen Science engages the public in the research process T

- Release of public datasets is important for career progression T

- F in FAIR stands for free. F

- Only figures presenting results of statistical analysis need underlying numerical data. F

- Sharing numerical data as a .pdf in Zenodo is FAIR. F

- Sharing numerical data as an Excel file via Github is not FAIR. F

- Group website is a good place to share your data. F

- Data should always be converted to Excel or .csv files in order to be FAIR. F

- A DOI of a dataset helps in getting credit. T

- FAIR data are peer reviewed. F

- FAIR data accompany a publication. F

Attribution

SH

Content of this episode was adapted from:

* Wiki [Open Science](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_science)

* [European Open Science Cloud](https://www.eosc-hub.eu/open-science-info)

* [Science is necessarily collaborative - The Biochemist article](https://portlandpress.com/biochemist/article/42/3/58/225220/Science-is-necessarily-collaborative).- Open Science increases transparency in research

- Publicly funded science should be publicly available

- FAIR stands for Findable Accessible Interoperable Reusable

- FAIR assures easy reuse of data underlying scientific findings