Reading and Interpreting STEM Charts

Last updated on 2026-03-04 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

We find that this lesson site is pedagogically very effective when used as lecture notes and learning activity instructions. We do not recommend lecturing with a screen share of the lesson site or projection of the lesson site. This combination of text, activity prompts, and verbal narration tends to exceed effective cognitive loads for learners.

But this lesson works best with slides that include 1) photos from the production of the Du Bois charts and the Paris World Expo, and 2) examples of Du Bois charts. We provide these images within the lesson site so that you can open them in separate browser tabs for display while you lecture.

Alternatively, you can copy and modify Google Slides deck with all of the images for this episode.

Subsequent episodes will have links to separate Google Slide Decks with their images.

Overview

Questions

- How can data visualization and creativity help answer important scientific questions?

- Why did data visualization become predominant in the social sciences earlier than for physical and natural sciences?

- How did Du Bubois use data visualization to challenge false biological theories of racial inequality?

- How did team science help Du Bois’ team to create impactful visualizations for the 1900 Paris exposition?

Objectives

Understand which of the four chart types used by Du Bois and contemporary scientists are best suited for different types of data and multivariate analyses.

Interpret how Du Bois used one of these chart types for an analysis that contradicted false, biologically-based theories of racial inequality.

Identify best practices for making charts accessible and engaging for broad audiences that are either present or missing from a Du Bois chart.

Ground your ability to to read and understand STEM charts by hand drawing a chart.

In this section we will explore charts developed for the 1900 Paris Exposition by Du Bois and his collaborators, as examples of effective analysis and storytelling.

We will examine types of data and the various chart types in some detail.

Video overview

Chart Types

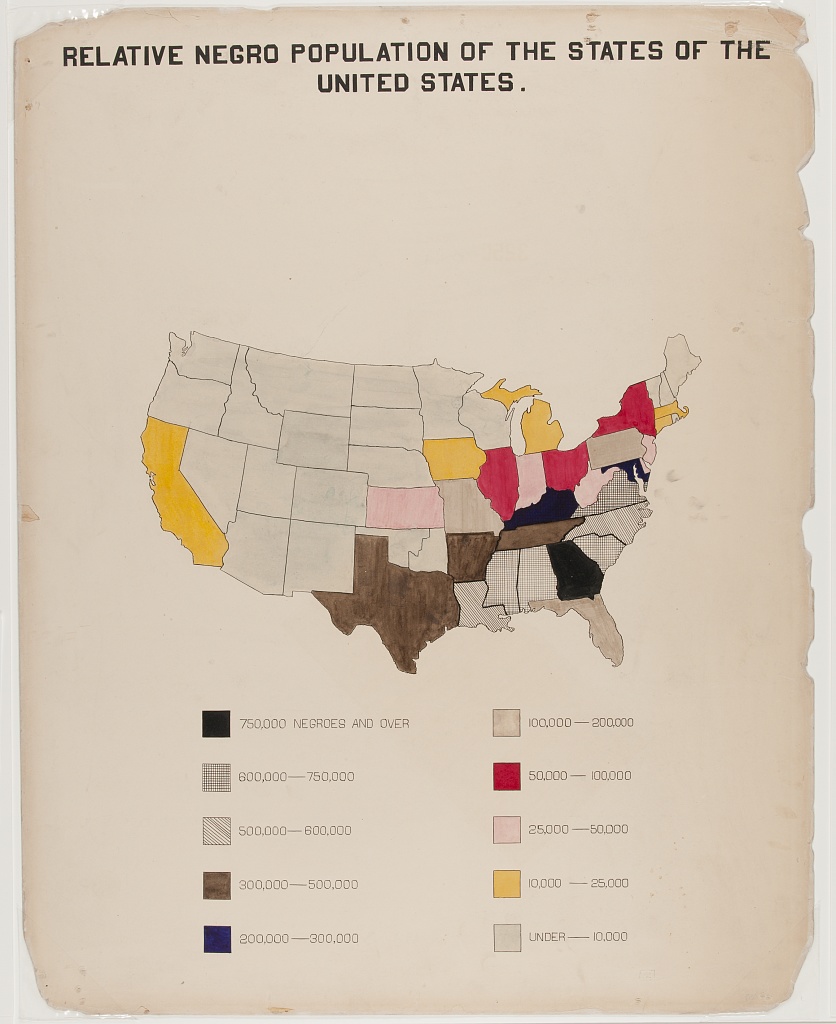

We use different types of graphs based on the types of data and relationships we are analyzing. Du Bois used variants of most of the major graph types that are still used today: (pie, bar, line charts, and statistical maps).

You can also explore more complex adaptations of these charts using the [Du Bois Resources repository for this lesson:] (https://github.com/HigherEdData/Du-Bois-STEM)

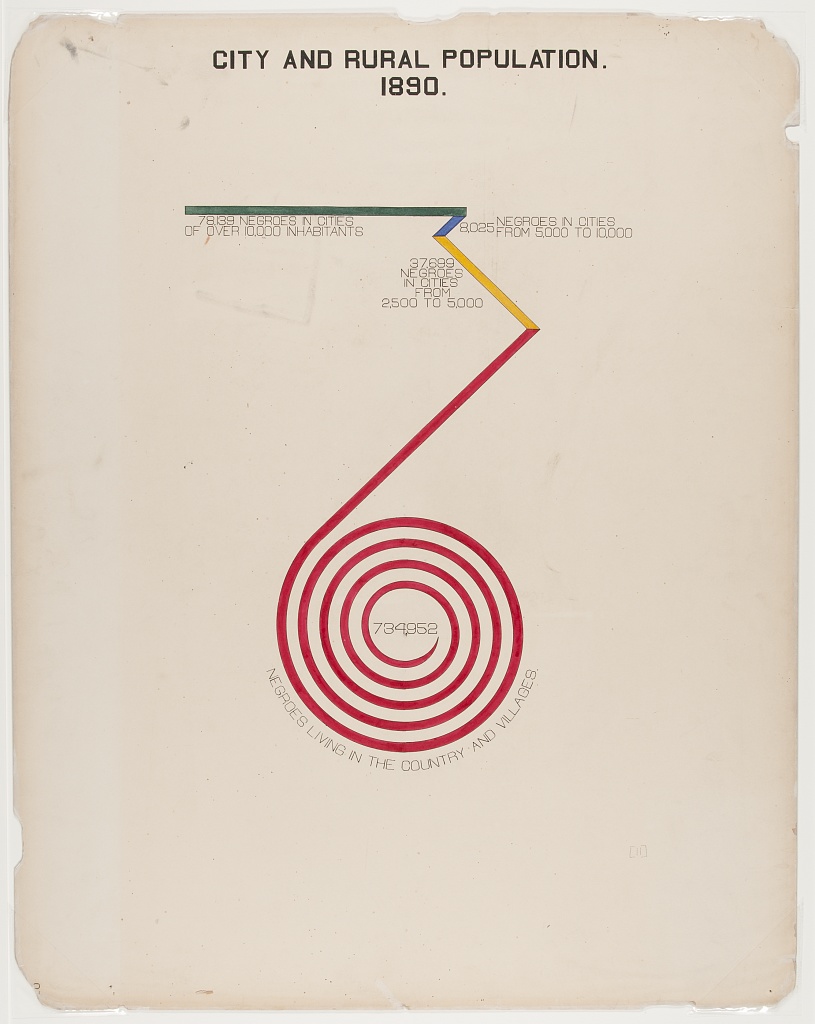

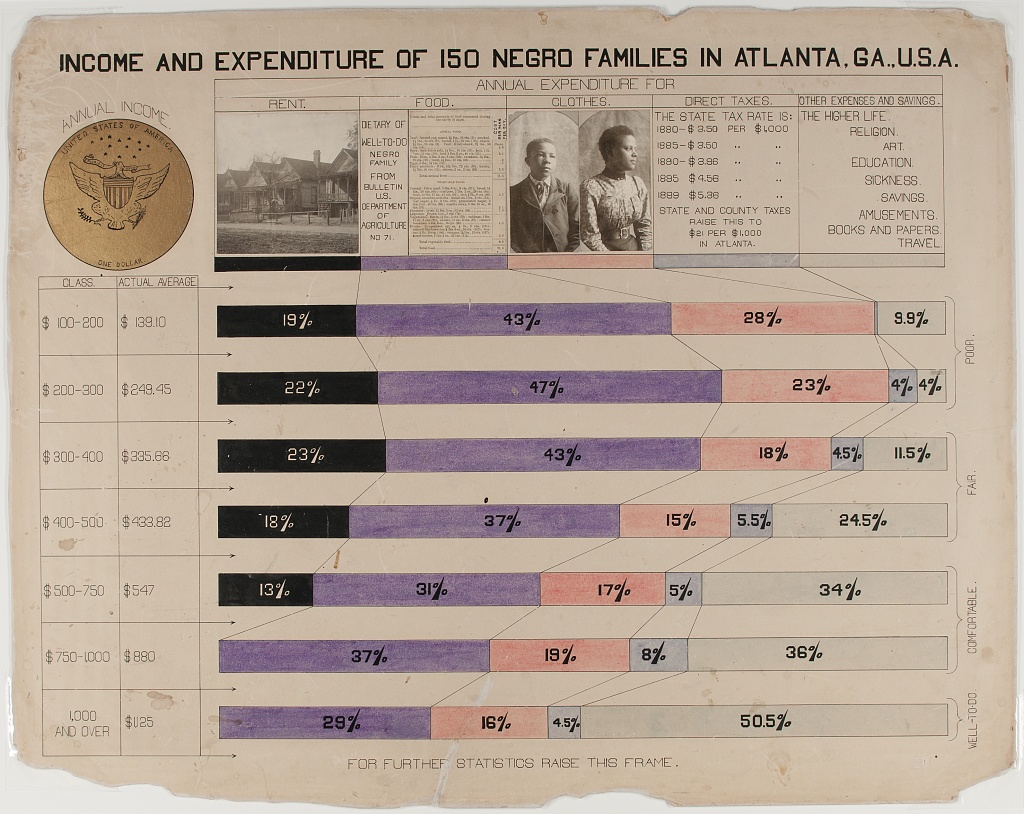

The types include the fanciful Du Bois spiral, stacked bar graphs, and integrated photographs.

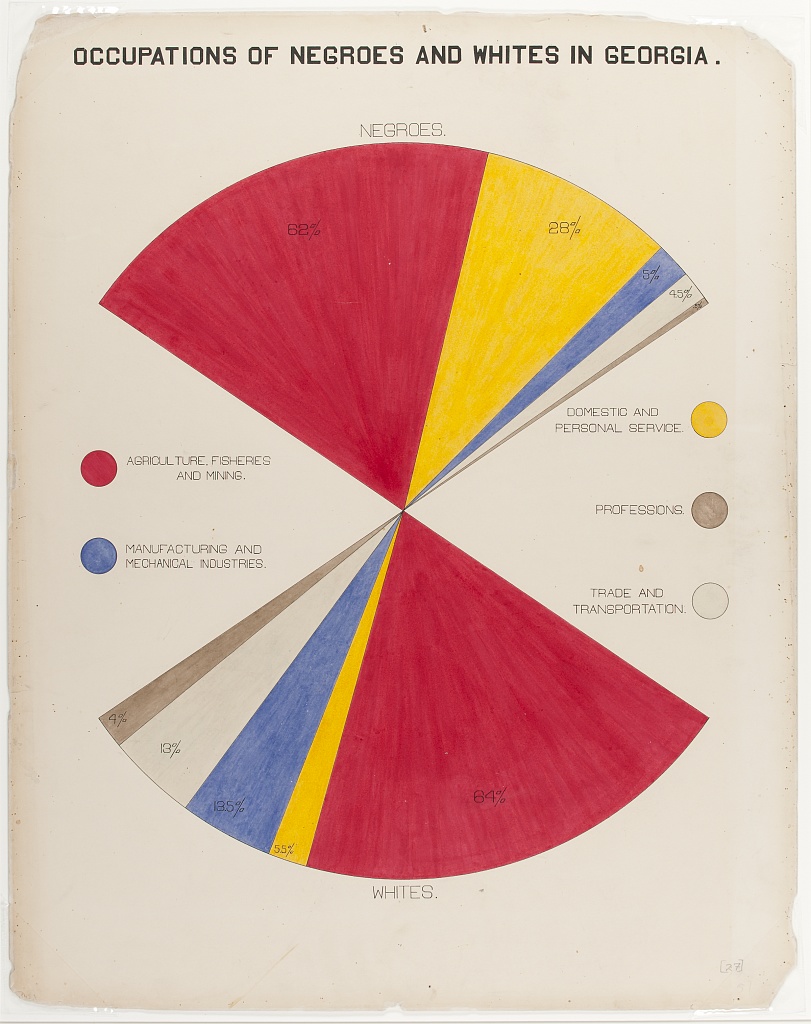

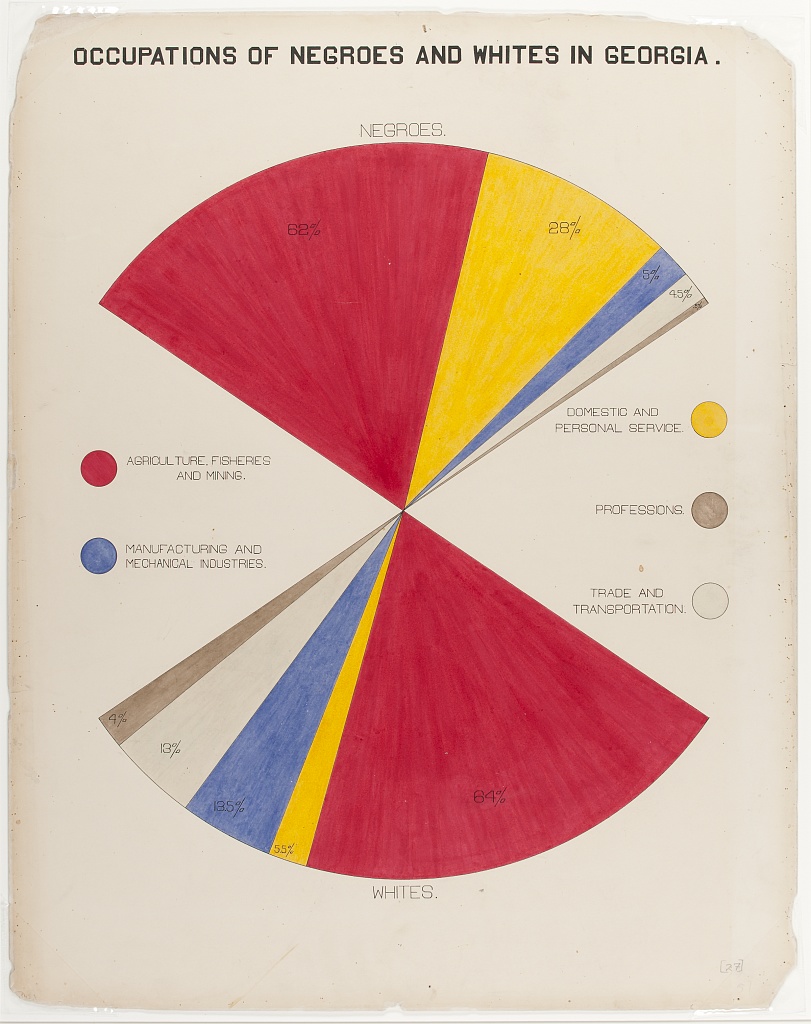

Chart Types: Pie Charts

Pie graphs illustrate the percentages of categories (like occupations) within a larger unit (like a population) where all the percentages add up to 100%.

This analyzes a one-dimensional distribution across one categorical variable.

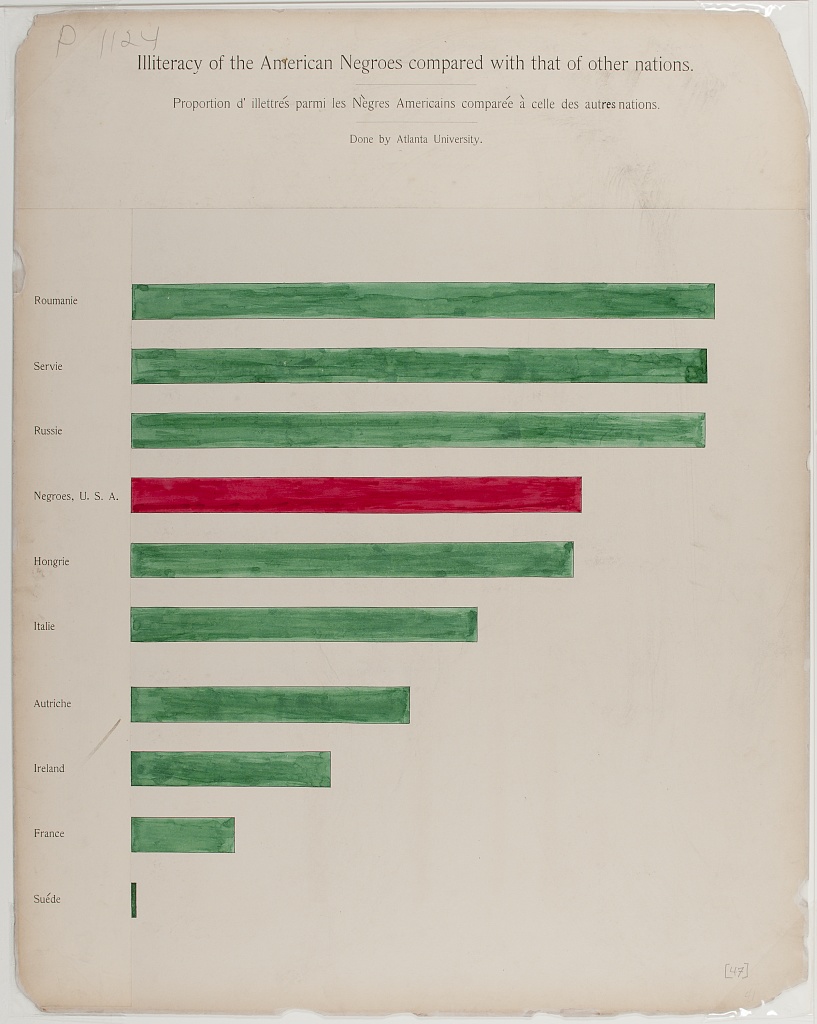

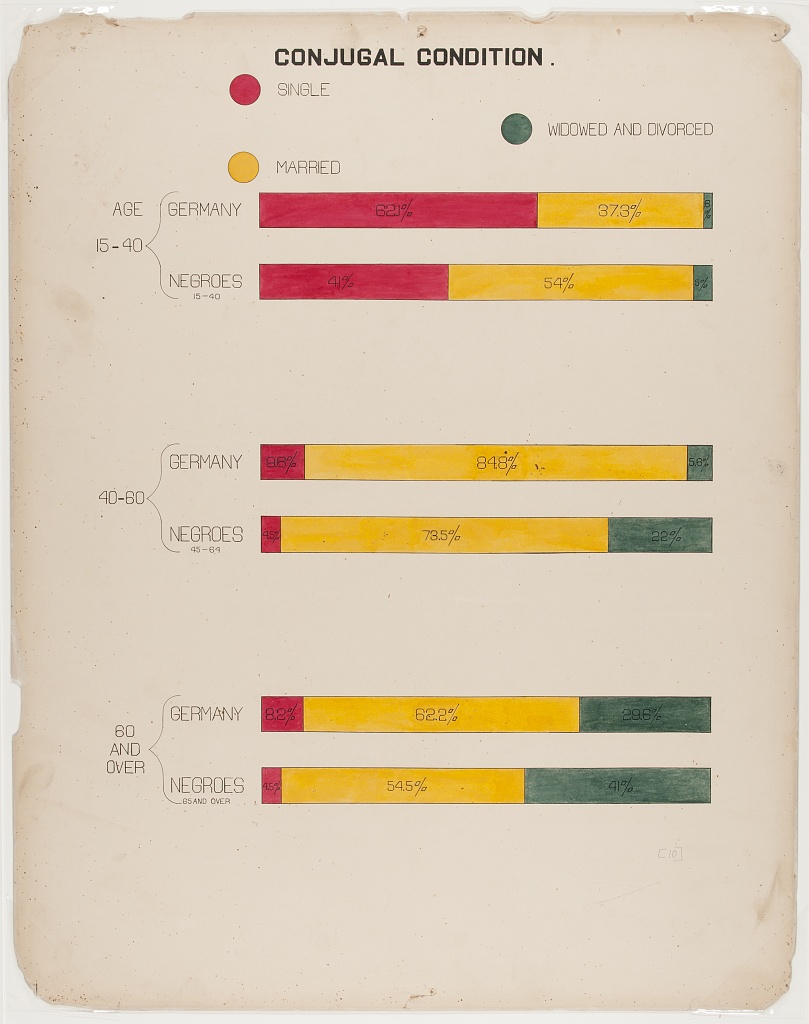

Chart Types: Bar Charts

Bar graphs compare frequencies or percentages of one category (like literacy) among other categories (like race or nation).

This helps us analyze two-dimensional relationships, typically between two categorical variables.

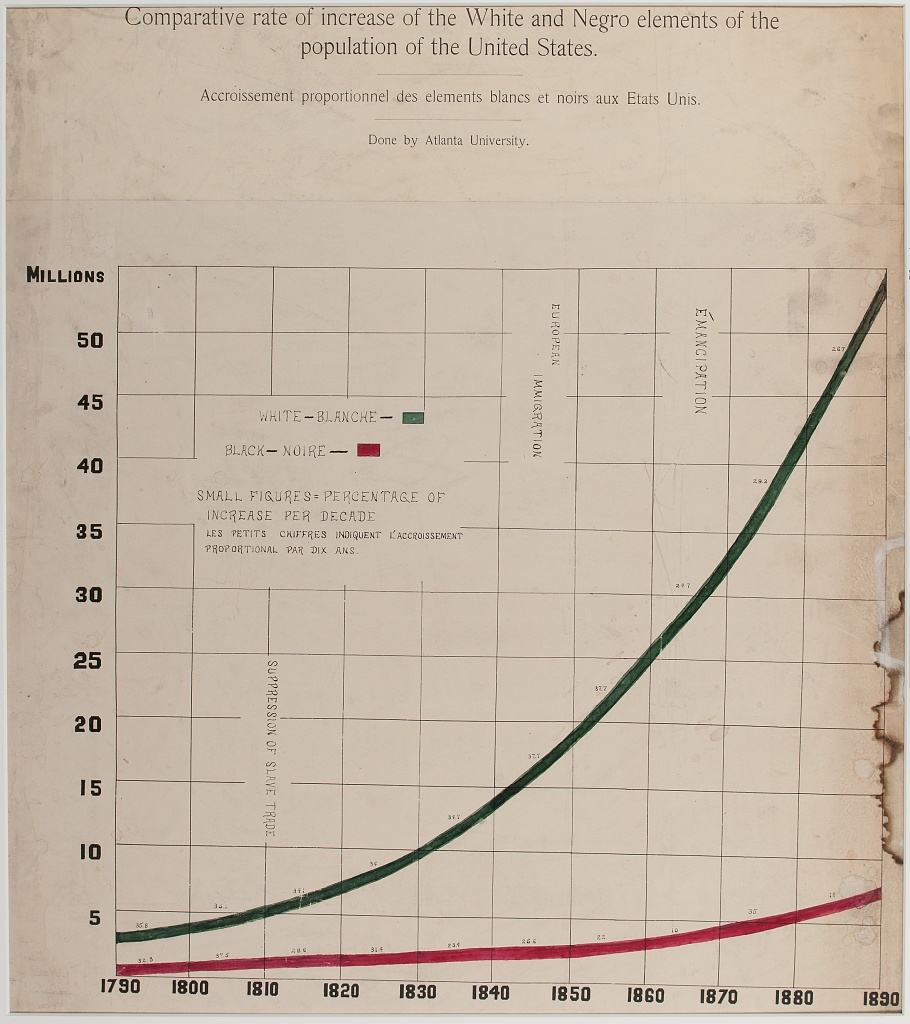

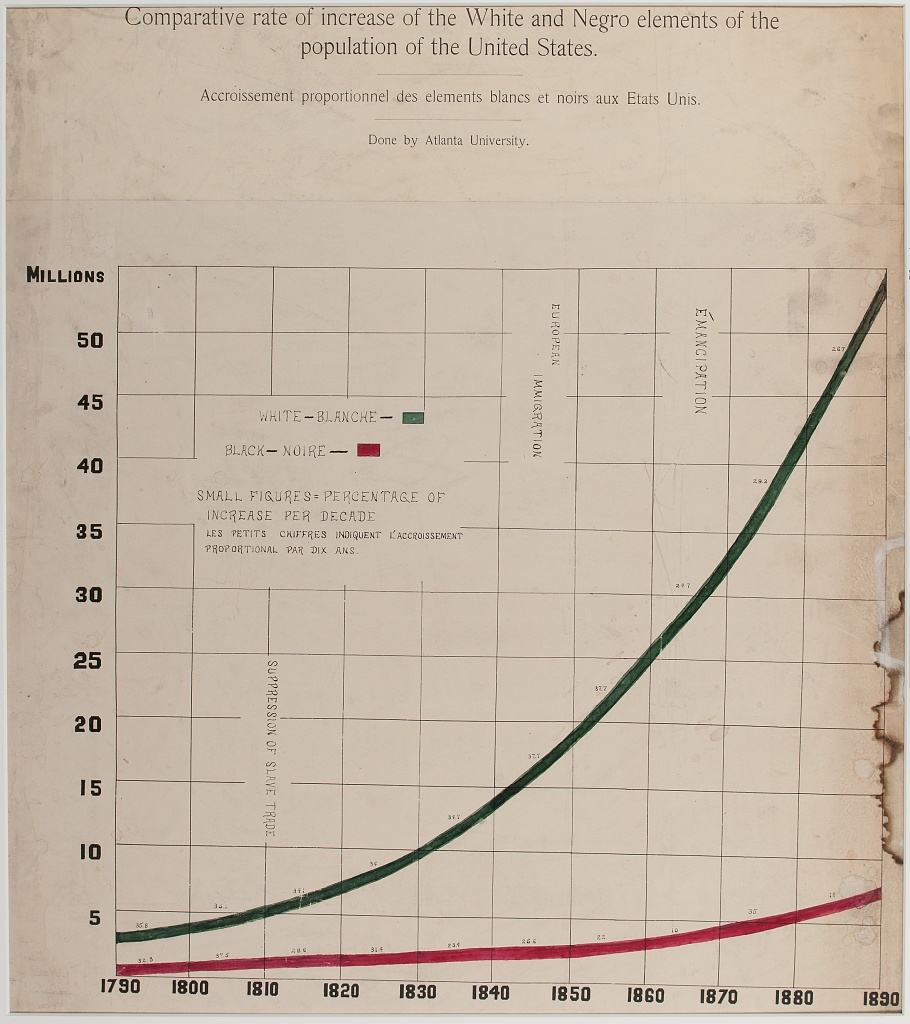

Chart Types: Line Charts

Line graphs plot frequencies or percentages of a continuous interval-ratio variable (like total population) on a y-axis among categories represented by different lines (like racial groups) over a third category of another ordinal or interval ratio variable on an x-axis (like year).

This analyzes three dimensional relationships between three different variables, including interval ratio variables.

Time series line graphs, with time on the x-axis, are the most common type of line graph.

Design Aesthetics and Accessibility

While Du Bois sought to make his visualizations accessible to broad audiences, advances in universal design practices do even more to make visualizations accessible to people with diverse visual, cognitive, auditory, or motor strengths and needs. Practices include:

Keeping visuals as simple as possible, presenting only information necessary for analysis.

Color-blind friendly use of color and contrast, avoiding over-reliance on color

Alternative text (alt text) that screen readers can use to provide an audio description of images.

Descriptive titles and labels

Offering both visual and non-visual formats

Including narrative text with context and summaries

Exploring Charts: a worked example

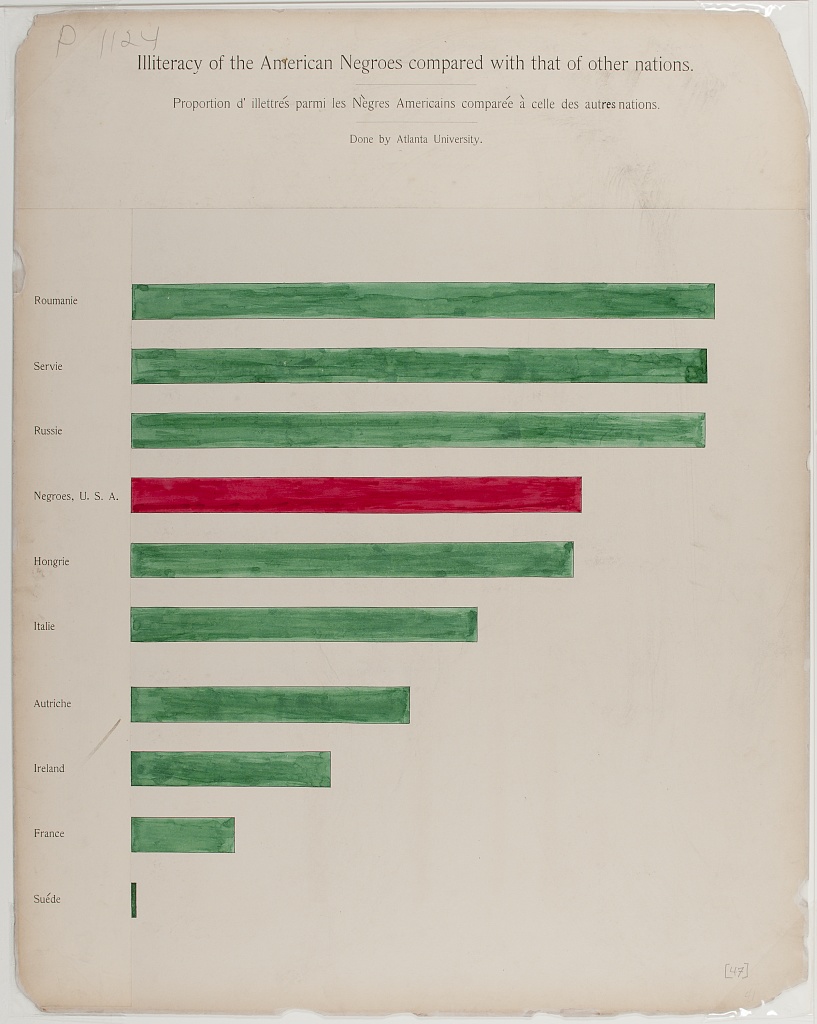

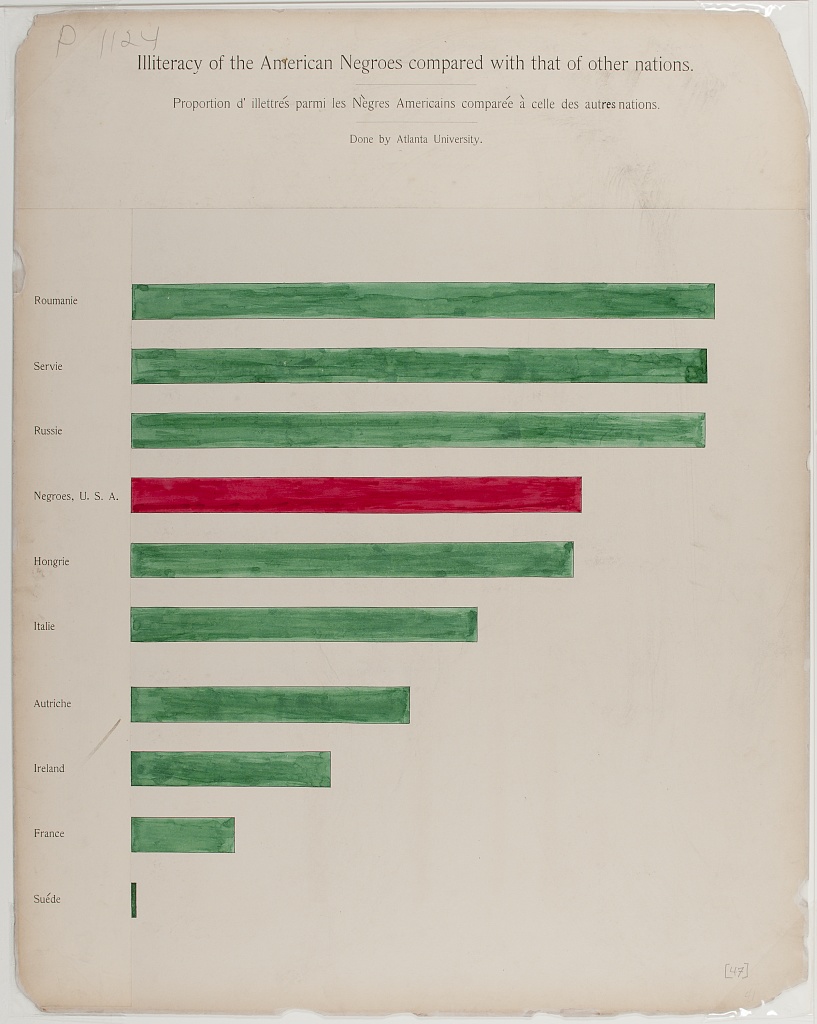

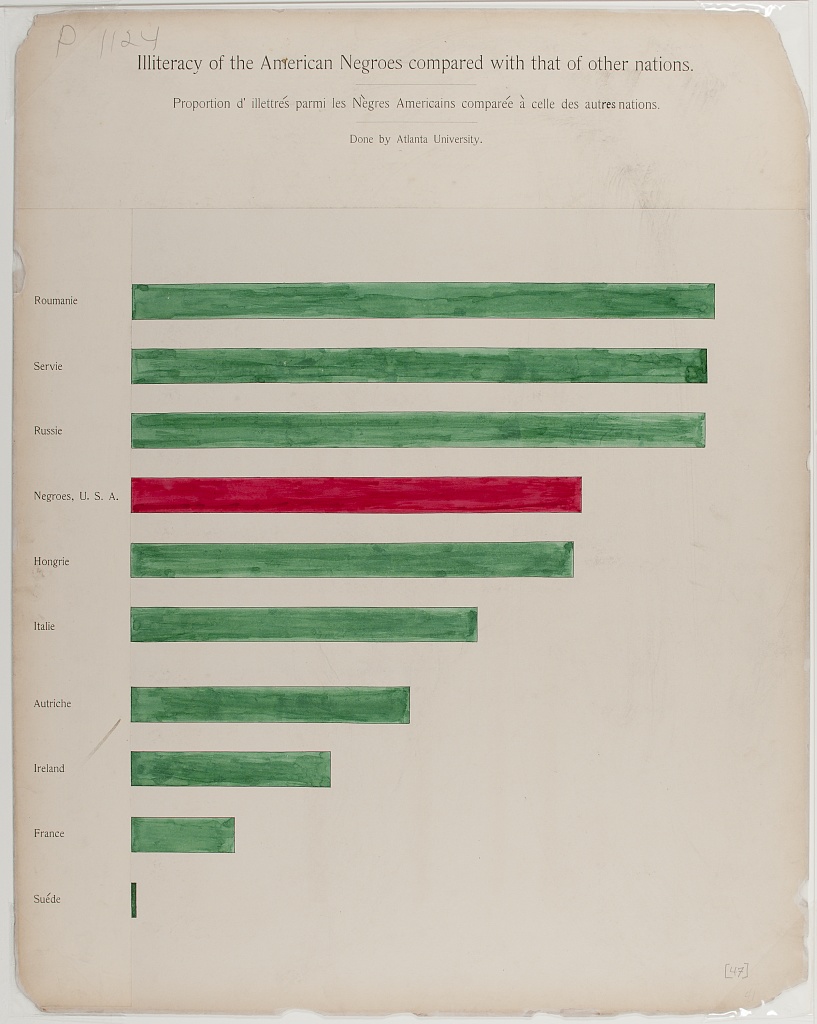

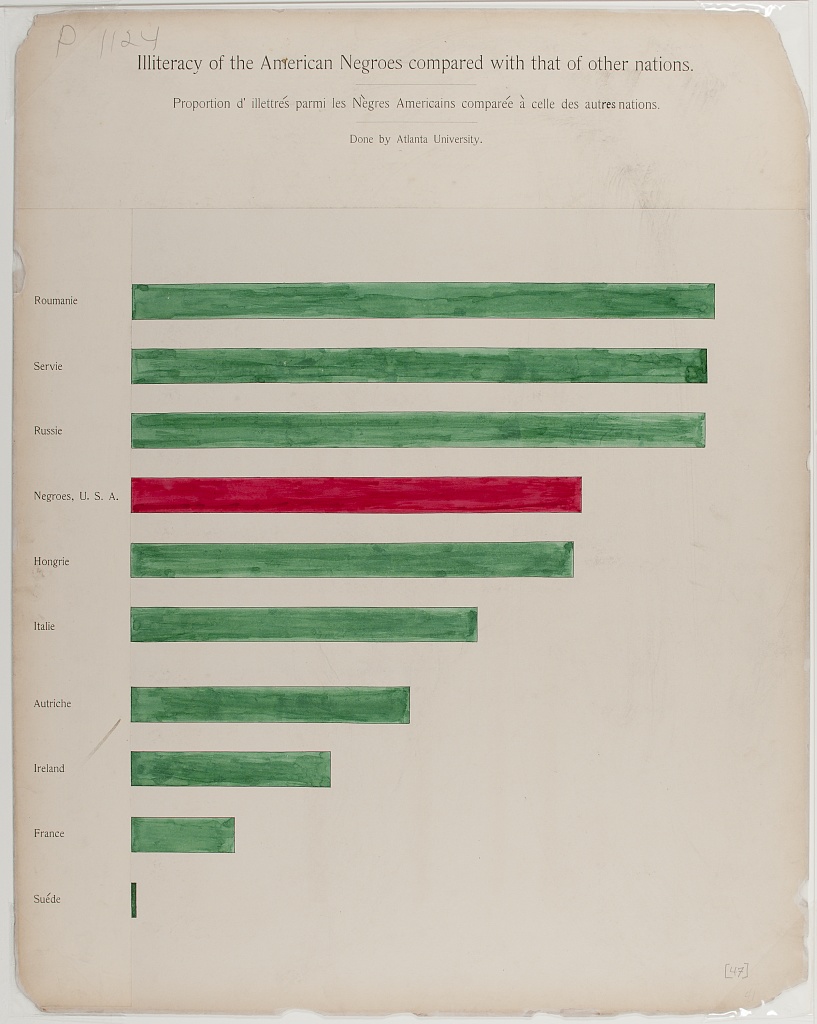

Illiteracy of American Negroes compared with that of other nations: Paris Exposition, 1900

How does Black illiteracy (the red bar) compare with other countries

Disucssion

How does Black illiteracy compare to literacy in other countries on the chart?

What is similar about the countries with higher illiteracy than Black illiteracy in the US?

Design Aesthetics and Accessibility

What makes this graph easy or difficult to understand?

How is the graph aesthetically appealing? How could could it be more appealing?

How does this graph take its audience into consideration?

What tools would you need to create this graph by hand?

This visual, a conventional bar graph, uses spot color to highlight the data for Black Americans compared to other countries, showing the illiteracy rate to be at the midpoint compared to other nations.

The chart portion is a large percentage of the canvas, simply showing the message.

Note the bilingual labels and titles (a nod to the venue and audience).

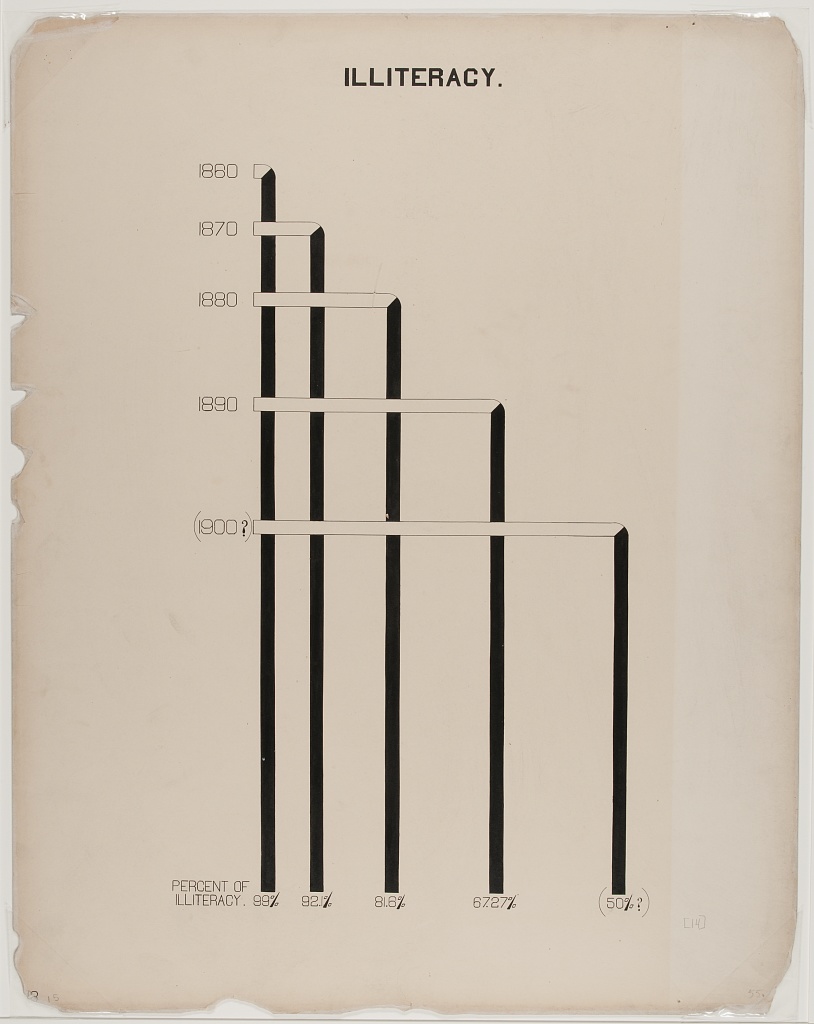

Context and Data Story

Du Bois presented his graph for illiteracy among Black Americans and other nations (left), together with the graph of Black illiteracy in Georgia from 1865 to 1900. What data story do these 2 graphs tell together?

Example: Re-Create with Modern Data and Accessible Design

Activity: Hand draw a recreation of Du Bois’ graph using the data below on college attainment today.

Building on the graph to the left, what accessible design improvements can you make?

Data:

Country College

Russia 60

Ireland 54

Sweden 49

France 42

Black U.S.

Residents 36

Austria 36

Hungary 29

Serbia 28

Romania 20

Italy 20- Even simple chart types can convey interesting meaning. Color man be used to emphasize points